Park Seo-Bo: The Godfather of Modern Korean Art

Park Seo-Bo. Courtesy Kukje Gallery. Photo: Choi Hang Young.

Park Seo-Bo. Courtesy Kukje Gallery. Photo: Choi Hang Young.

Park Seo-Bo is widely recognised as the godfather of modern Korean art. The artist played an instrumental role in nurturing the careers of emerging artists and for his own contribution to the formation of Dansaekhwa—the Korean monochromatic painting movement that emerged in the mid-1970s.

In the spring of 2018, Park was recognised with the Asia Arts Game Changer Award, joining the ranks of past honourees such as Cai Guo-Qiang, Hiroshi Sugimoto, and his contemporary Lee Ufan.

Born in 1931, Park's adolescent years coincided with the end of the Japanese colonial era. As a student, his artistic practice was affected by the devastation of the Korean War, which led him to work in found materials. Park learned to use scrap metal as frames for his canvases and leftover supplies scrounged from his art classes at Hongik University. His firsthand experiences of war became the fodder for 'Primordialis', a dark and moody series dating to the 1960s.

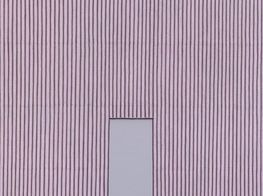

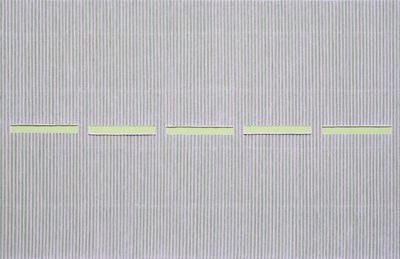

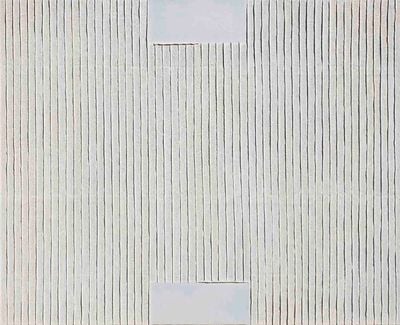

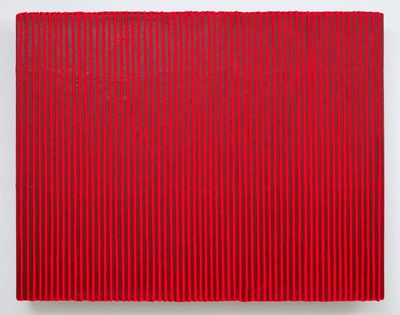

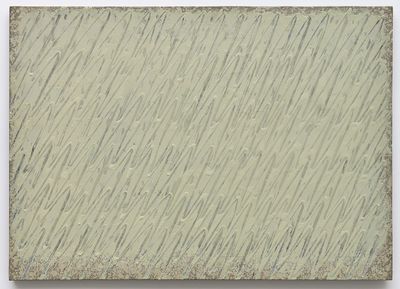

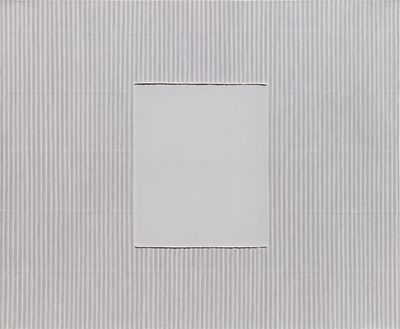

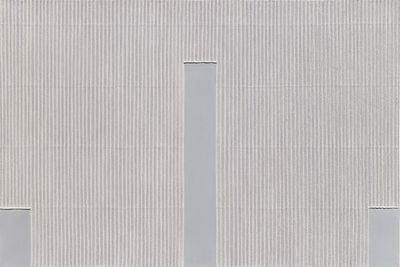

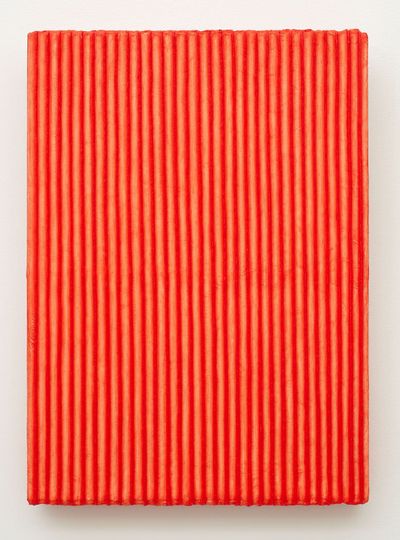

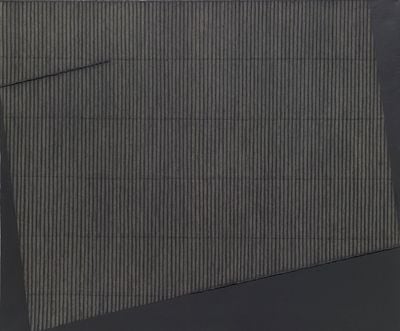

In 1961, the artist received a UNESCO scholarship to study in Paris. During this period, Park became further acquainted with the principles of Art Informel, a movement that had great influence on the developments of Dansaekhwa. Upon his return to Korea in 1962, Park became a professor at his alma mater until 1966, and in 1967 he began the first of what has since become his best-known series: 'Ecriture'. These neutral-hued expanses are created by applying gesso or paint to the canvas, which Park manipulates when still wet to carve rivulets in the painted surface.

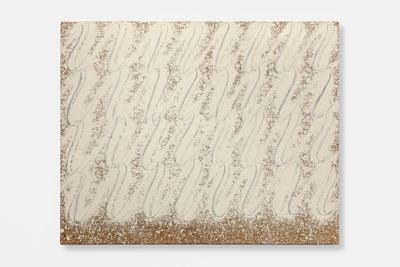

Park's tireless experimentation has also involved traditional Korean paper, hanji, which he began incorporating in his works in the 1980s to enrich his monochromatic canvases with further texture. In Shanghai, a selection of these textural works will be included in the Powerlong Museum's exhibition Korean Abstract Art: Kim Whanki and Dansaekhwa (8 November 2018–2 March 2019), the first comprehensive exhibition of Korean abstract art to be held in China.

In this conversation, Park looks back on his career, offering insight into his ceaseless drive to paint, the conflicting poles of Western and Eastern art philosophies, and the genesis of his most iconic series, 'Ecriture'.

IMIn a recent interview you said that artists must reflect on their own time period, rather than attempt to encompass a sense of historicity in their work. What would you say has been the most inspiring source of reflection for you in this decade?

PSBI think that the reflection on one's own time period is something that is naturally integrated into one's system. This organic phenomenon becomes physically imprinted onto my being, which in turn is projected through my work. In other words, as a constituent of the time in which I live, I absorb the milieu like a sheet of Korean paper absorbs watercolour. All sundry attributes of the period are digested and regurgitated as they are, in the name of painting.

First, in order to become the greatest artist of a certain period, one must possess the insight to comprehend the zeitgeist—the ability to penetrate all subtleties of one's time and intuitively move forward in the right direction. Such ability cannot be learned from books. Secondly, one must have undying passion—nothing can be done when you lack the passion or if it simply dies out. These two factors must always exist in any great artist.

IMYou are known to paint every single day and have done this since your twenties. This dedication over the years has resulted in a massive collection of paintings that you have said are like extensions of yourself. What has provided this daily drive?

PSBLet's put it this way: I feel ill at ease when I don't paint. It's as if I am re-affirming my own vitality through painting. Even though painting can be torturous when I'm feeling mentally blocked, I'm never as happy as when I am painting. I get anxious when away travelling for a few days, or when I take a bit of a break. Whenever I return, I rush back to the studio and pick up the brush again, no matter how tired I might be.

From my twenties until late November in 2009, I spent 14 hours a day painting. When I was a college student, we didn't have the proper equipment to make art. I stayed late after classes to work; we were in the middle of a war, so there would be several grades all grouped together in a single classroom. I would work until late in the evening, then sweep the floor and tidy up the classroom so I could collect discarded pencil tips, Conté sticks, and charcoal.

If I didn't have any materials, I would use dirt to draw. Poverty is the mother of creation and creativity—one always finds tools with which to project one's passion in extreme cases of poverty and desolation.

IMHave you ever had a period in which you could not paint?

PSBI've never experienced such disappointment. In some ways, I was never fully in the habit of complying with the traditions and canons of Western art. Perhaps this is because the land on which I live is filled with all the adverse elements of life: violence, war, and poverty. A combination of all of the above is what constitutes and moves society today. To live as a hermit, secluded from this turmoil, would be an act of distancing myself from the time in which I live.

As mentioned before, I consider myself as a sheet of Korean paper that absorbs watercolour. I witnessed so many deaths in my twenties when my country was at war—I even saw my friend's leg get blown off during a bombardment. At that time, I wanted to fill my works with the last words of those dying. This is perhaps the reason why I was so preoccupied with 'war aesthetics'. Works from my 'Primordialis' series, including Primordialis 1–62 (1962), are products of my endless struggles to portray these invisible tragedies.

To reiterate, I am not interested in the artistic movements of the West. But the world is like a series of toothed wheels that interweave one another. Korea may be a small wheel compared to others, but without doubt it is adjacent to much bigger wheels. That's how the earth works, really. There's a kind of simultaneity that exists in each particular time period, which is why this sense of simultaneity is naturally instilled in my works. There's a small world that is weaved from the small wheel.

IMThe 'Ecriture' series was said to have been inspired by your son in 1967 when he was in grade school: he began to scribble across a page after becoming frustrated by the restrictive nature of practicing his penmanship on gridded manuscript paper. Could you speak to this origin?

PSBOn 26 December 1966, I submitted my resignation letter to Hongik University, where I tenured as a professor. I quit my job without planning the next steps and just read books all year around. I read books on the East. You see, Korean scholars back in the day sat in sarangbang (reception rooms), clearing their throats and grinding ink all day. They repeated these mundane actions over and over again. While repeatedly grinding the ink, they found their thoughts and feelings—such as anger—more at ease and orderly.

Through this repetitive action they rendered themselves pure and more self-aware. That was their method of removing evil and cultivating goodness to reach purity. After pouring over books on these Korean scholars, I realised that I wanted to live my life as they did. In order to do so, I had to empty myself completely. I also realised that a work of art is not merely an image that sits atop a canvas; a work of art has to be self-cultivated and achieved through purification.

In other words, I needed to empty myself completely and not make any expressions on the canvas that would suggest my thoughts or feelings. That was the starting point for my 'Ecriture' series. I realised this truth in theory but was not so sure how I would go about drawing it. \

One day, I saw my second eldest son (who was three years old at the time) writing in a grid notebook on his older brother's desk—he wasn't even able to hold a pencil properly then. He repeatedly and clumsily wrote in and erased the notebook, struggling to keep his characters within the margins, until the pages crumpled and tore from the pressure. He then became frustrated and scribbled furiously all over the page. He quit. That was exactly what I was looking for.

IMThe paintings didn't make their debut until 1973, during a period of military dictatorship in Korea. Many have drawn the interpretation that the series was an expression of political subversion—what are your thoughts on this reading and could you discuss the debut of 'Ecriture'?

PSBThat is incorrect. My personality tends to be quite explosive and I could be considered hot-tempered, but that is why I am also extremely careful. I wasn't sure if my 'Ecriture' pieces could be stand-alone works until 1973, it's as simple as that. I worked on two series titled 'Hereditarius' and 'Illusion' in the late 1960s. I debuted works from the two series but kept 'Ecriture' to the side. The latter had to mature as much as possible. In 1967, I developed a new habit where I turned existing works over so that no one could see what I had created. Then, I would place a new canvas over the back and paint over it.

For 11 years, starting in 1969, Lee Ufan would stay at my home for a week or two whenever he would visit Seoul. One day, Lee came back home very early, before the sun had set. I was in the midst of finishing up a work sized at 200 ho (approximately 260 x 190 cm) when he walked in and saw the painting. I told him that I had been working on this piece in my spare time since 1967, and that I wasn't so sure it could be considered a work of art.

Thankfully, Lee marvelled, suggesting I do a solo exhibition in Japan. That was in 1971, which meant that I had to aim to open the show in 1972, but all the well-received galleries were fully booked for the upcoming year. I eventually agreed to open my show in the June of 1973, having decided to give myself more time to further mature my practice.

I wanted to debut my works in Korea first, then take them over to Japan, but Lee suggested debuting the works in Japan first. Given the domestic artistic climate at the time, my works would have received blatant criticism and people would have questioned whether they could even be considered art. He knew that my work would be the subject of much domestic attention if I were to showcase them in Japan first.

In 1983, an International Paper Conference was held in Kyoto. There, I was able to meet and be in discussion with some amazingly influential minds of the century, including Robert Rauschenberg and David Hockney. Towards the end of the discussion, one Western audience member asked a question: he claimed to be rather well acquainted with the Korean contemporary art scene and found my works extremely ascetic and self-restrained.

He asked if this was a display of resistance against the repressive dictatorship of the Park Chung-hee administration, along with the relationship between my works and the zeitgeist. 'I don't veer towards the political. My works are manifestations of the struggles I have with myself,' I answered.

That question still lingers in my mind today. I ask myself if I really had to single-handedly rebuff the man's question that day—perhaps the zeitgeist had indeed pervaded my practice. During conversations about that question, I've said that maybe the era has indeed affected my practice and works. The elements of time and the zeitgeist might have subconsciously entered my work, because I am an object of my time and I am influenced by the time in which I live.

IMWhen did you begin to incorporate hanji into your works? What drew you to this medium?

PSBI have used hanji since 1962. Other kinds of paper, such as the classic A4, newspaper, art paper, and parchments do not absorb colour when you layer it on them. Layering paint over paint just makes the colour more vivid and jumps out at the viewer. For the materials to permeate one another, the colour must unite with the paper. Hanji absorbs colour and becomes one with the paint. The Eastern view on nature disagrees with the idea of revealing oneself. Hanji absorbs everything because as a paper medium, it is rooted in this Eastern perspective.

Materiality cannot arise from regular paper. It can only evidence the traces of action. But materiality can arise from hanji when it is pushed like this. It is the kind of paper with which an artist can best express its materiality. Some even say that hanji is the best kind of paper in the world. There's a saying that hanji can survive a thousand years and more. That is, unless someone tries to deliberately destroy it.

IMThe question of mark-making has long characterised the 'Ecriture' series. The lines in your earlier works were made with pencil, and the addition of hanji was a further development in an investigation of traces—and the subsequent emptying of the individual mark. In an increasingly digital age (where it is simultaneously easier for an individual to leave their mark as well as for a text to be anonymised), how has your perspective on mark-making shifted?

PSBI am someone who has lived with the analogue for about 70 years. I was ushered into the digital era in my seventies. That was the dawn of the 21st century. I had so many thoughts running through my mind because I didn't have the confidence to survive the digital era of the 21st century. But in the end I resolved to live a better life in this so-called 'better' world.

To put it frankly, the digital era of the 21st century is a stress ward. People who cannot keep up with these rapid changes become so-called losers, failures, and misfits. People are all suffering from stress. We mustn't tolerate the violence of images. I stand firm in my belief of emptying oneself completely. I hope that my wider audience can heal through my works. I never really used colour in my works until after the turn of the 21st century. I use colours that heal.

Until the 20th century, paintings from the analogue world consisted of a canvas that would depict an artist's regurgitation of his or her thoughts or opinions, then the viewer in turn would perceive an image 'from' the canvas. However, there is no 'from' anymore. Paintings from the 20th century bombarded the viewer with images that jumped out of the canvas.

Subsequent generations of paintings shouldn't do that. In a world full of violence where many are unstable and some even go out on mass shooting sprees, just looking at a certain kind of painting should stabilise the audience and restore them to peace. That is the result of healing with art. The audience shouldn't feel pressured upon seeing a work of art; their anger and suffering should be sucked out like an absorbent paper and leave only feelings of comfort and happiness. That's my idea of art today.

IMSpace, particularly from the perspective of nature, is key in your compositions. The calm and meditative quality of space is reflected in the 'breathing holes' of your work. Is the process of creating your work in itself meditative, or do you find that it is the result that takes you there?

PSBArt in the past always had intent or purpose, but I empty out everything through art. I enter into something akin to a meditative state after emptying everything out. The foremost spirit of Dansaekhwa is the lack of purpose in action. No purpose should exist behind an action or behaviour. The second spirit of Dansaekhwa is the repetition of action. One can reach a level of zen only after this repetitive action. The third is the combination of the physicality and spirituality formed by this course of repetitive action.

IMRecently, you've made a return to painting in a smaller scale. How has this change affected your practice?

PSBI've always painted in larger scales, but the reason why I have returned to smaller paintings is because most living rooms today contain sofas and TVs, and there's nowhere to hang artworks. The walls are made with new industrial materials that don't allow for the hanging of larger paintings. This is the reality of our world, and it will only become exacerbated in the future. Paintings will only be viewable in museums and institutions. My smaller works can be hung beautifully in domestic settings, and can coexist with the logistical limitations of newly-built homes. That's why I've returned to smaller paintings.

IMYou've been called the 'father' of Dansaekhwa for your pioneering role in abstraction in Korea, as well as the 'godfather' of modern Korean art for your support of artists and exhibitions. You taught at Hongik University for decades, overseeing the education of generations of young artists. What drew you to teaching when you first began at Hongik, and what has been the most valuable aspect of your experience as a mentor to up-and-coming artists?

PSBFrankly speaking, when I began it was to make a living. Paintings don't sell; at least not regularly. That is why I had to become the breadwinner by teaching my students and children, and becoming a professor was the best way to do that. In the past, art students were simply told to draw a vase on a lecture desk, or some apples in a basket. Having questioned the system from an early age, I developed a set of principles as I began to teach my own classes.

First, never take after your professor. Second, do not take after one another. Because when students see someone who is only slightly better, they all try to mimic that one slightly better person. Third, do not be indebted to any kind of history. That principle was meant to caution my students against repeating what had already been done in the past. I was called in by the then-president of Hongik University, who asked me who the students should take after if not their professor. I answered, 'To become like someone else is failure; you (the then-president was from the Department of Mathematics) can teach your students to follow mathematical formulas but we don't have any formulas to follow. We each need to create our individual formulas.'

On another occasion, I went to a junk shop with the money I was given for croquis models and to buy still life objects. I brought children's tricycles, toys, and other grimy objects back into the classroom and made the class into a whole new junk shop; some objects were hung from the ceiling or on the walls, and others were simply discarded on the floor.

I told my students to create a drawing by assembling what they wanted to draw on paper. They had to assemble not by moving these objects around, but with their imagination. I told them that this was an exercise to enhance their sensitivity to composition and ability to interpret spaces in relation to the objects that inhabit them. My students improved drastically after that exercise. Perhaps I was able to thankfully give way to many great artists because I taught tirelessly; even during vacation, my wife would bring my breakfast and dinner to school because I was teaching my students all throughout.

In Europe, I noticed that even the lowest of the lower class had a vase on their dining table, which would be sporadically filled with wildflowers picked from the meadows or fields. The dining table would also have a basket of fruit for dessert.

When Cézanne saw that basket of fruit, he realised that the fruit could be an object derived from the spherical model. That's why he placed them on the table and rendered the fruit as the subject of his invaluable masterpieces. That artistic tradition travelled over to the Eastern hemisphere and became the norm. I think that's quite funny. It was my job to deconstruct, analyse, and criticise 'traditions' such as this from a different angle. —[O]