Pierre Huyghe: The Artist as Director

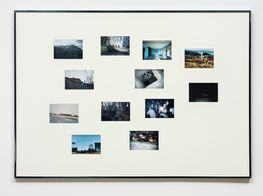

Pierre Huyghe. © Okayama Art Summit 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Taiichi Yamada.

Pierre Huyghe. © Okayama Art Summit 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Taiichi Yamada.

Pierre Huyghe is a producer of spectacular and memorable enigmas, with works that function more like mirages than as objects.

Abyssal Plain (2015–ongoing), his contribution to Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev's 2015 Istanbul Biennial, was installed on the seabed of the Marmara Sea, some 20 metres below the surface of the water and close to an uninhabited island where stray dogs were once sent to die. Apparently, the underwater installation consists of a platform on which found objects and artefacts sourced from around the Mediterranean have been placed, destined to become part of the habitat. During the Biennial's opening week, special boats were organised to take visitors to see the site; a trip that took hours and which basically yielded no return, aside from the journey itself.

Movement and the absences it creates are a constant presence in Huyghe's work. For Nicolas Bourriaud's 1996 exhibition Traffic at the CAPC musée d'art contemporain in France, Huyghe staged Singing in the Rain (1996): on the day marking Gene Kelly's death, a performer stood on a pedestal and sang the song from the movie after which the work was named, leaving the shoes and raincoat in situ for the rest of the show. The colour film A Journey that wasn't (2005) edits together film from an expedition to the Antarctic circle and footage from a concert staged on an ice rink in New York's Central Park.

In another ambitious installation presented at dOCUMENTA (13), also curated by Christov-Bakargiev, Huyghe created an outdoor environment centred around a concrete statue of a reclining figure with a beehive for a head. The sculpture, modelled after a 1930s work by sculptor Max Weber, was nestled amid dirt mounds, compost heaps planted with all kinds of plants, and cement blocks; a sleek white greyhound named Human, its leg painted pink, was left to roam the overgrown landscape. For Huyghe, this was a scenography in which organic plotlines grow, evolve, and intertwine beyond linear formats, narratives, and closed frames.

Keeping things open is perhaps a key concept that runs through Huyghe's practice—a gesture that manifested in No Ghost Just a Shell (1999–2002), conceived in collaboration with Philippe Parreno, for which the artists purchased the rights to a female manga character named Annlee, and invited others—including Rirkrit Tiravanija and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster—to create works using her form.

At the Okayama Art Summit 2019, Annlee made an appearance in the video Two Minutes Out of Time (2000), projected into an empty vitrine at the Hayashibara Museum of Art, in which she delivers a monologue describing her existence as memetic form. In the same space, a young girl introduced herself as Annlee made flesh in Tino Sehgal's performative piece Ann Lee (2011–2019), with Ian Cheng's BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018–2019), an AI simulation that can be fed by online observers through an app, installed nearby.

This collection of works formed one section of the Okayama Art Summit exhibition, which Huyghe directed, following the artist's participation in the inaugural Summit in 2016, directed by artist Liam Gillick. Titled If the Snake, the exhibition was a quintessential Huyghe staging: more of a scenario than a show, projecting a landscape future in which the world, post-apocalypse, must begin again.

In this conversation, Huyghe discusses his experience of directing the Summit, which was formulated as a porous, 'living entity' inviting growth and change.

SBYou participated in the first Okayama Art Summit as an artist, directed by Liam Gillick in 2016; from there, how did you step into the role of artistic director of the 2019 Summit? Do you see a connection between the Summit you have directed, and the one you participated in as an artist back in 2016? Particularly given the theme of the first Summit, which was about 'development'.

PHIt's good that you say directed; Liam was trying to avoid the curator hat, so he called his role 'director'. If there is a continuity between Liam's Summit and this one, it lies in the way the artists are considering the condition, construction, and production of the work in order to change and avoid a linear system of development.

I once read Liam's text on Development, which was the title of the last edition, but that was it. I didn't try to mirror, be against, or be in continuity with the first Summit, in a positive and constructive way. I really tried to consider the format of the exhibition as dramaturgy: to give more presence to the exhibition without giving it a theme or an approach. It is really about the work itself and the particularity of each thought, so that each might find its own continuity with another work, or thought, or not.

SBThe way you staged the show recalls the way you described your retrospective at LACMA in 2015. There's an interview where you talk about how you took the exhibition as an object in itself and how you didn't want to have an overarching meta-narrative or create some kind of scripted space.

PHI'm not jumping from being an artist to becoming an art historian or curator. I don't have the tools for that, though it's not even about the tools—I don't have an interest to take on that approach. The only thing that I could say is that the approach to this exhibition is the only one that I could have.

I really tried to consider the format of the exhibition as dramaturgy: to give more presence to the exhibition without giving it a theme or an approach.

SBThe show feels like a Pierre Huyghe artwork, actually: the works on view feel like elements in a greater, more obscure whole rather than points in a linear experience. There is a kind of open inaccessibility that reminded me of the 13th Istanbul Biennial, when you staged a work in the middle of the sea that no one could actually see.

PHAs if it were part of an ongoing fiction, right? I find the mono-perspective on something is thoughtless. If I can have an image of everything at once, aligned and captured, it also assigns me to a position, the one from which I can capture everything. It is not about that very frontal relation—the transaction between subject and object—rather it is an operation of de-framing the way we see or know. As one navigates a site of uncertainty—of possibilities—meaning can be assembled, or not, depending on where you come from and where you are going.

SBExactly. You once said that you were interested in translation and movement and corruption from one world to another.

PHYes, I see that more as a kind of sedimentation in which you can go from different planes that provide different levels of access; different levels of sedimentation. And yes, it is corrupted.

SBHow does that fit with your nonalignment to a curatorial position for this exhibition, and with the process of deciding on the artists—and works—that you selected to show?

PHBy default, it's complicated. The work I was drawn to was the work that had the capacity and ability to modify, be porous, react, and engage with consciousness; different modes of intelligence, rather than something that would be, let's say, a compact object. This is not an alignment of compact objects. In a certain way, it is about authorising a leak: whether biological, chemical, or even thoughtful—a leak between A and B that is not driven by a master plan. There is a particularly inherent quality when it comes to the particularity of each of these features or work—of being able to modify as a thought form. When it came to choosing the works, I was more interested in artists who construct worlds that have the capacity to endlessly change, rather than as makers of things.

SBSo you were quite intuitive when you were selecting works?

PHIn a sense, it's a game between trying to conceive, and trying to apply a structure of thought. That structure was not intended to be a net that could constrain the artist under different thoughts, or under a script or score. We are not just notes on a line to be played. I find it problematic to consider the exhibition format as a medium that has no quality, as if it's a neutral thing. It is not a neutral thing.

I consider the exhibition as a living entity that can grow and change in indifference to any witnesses. The opposite would be a theme, addressed to a public, but by doing so, it framed any possibility. I did not select the works under that umbrella, rather as features necessary in a complex system.

SBThe title of the show, and the emphasis on the snake, encapsulates ideas of continuity, timelessness, enduring change; the snake is also associated with various myths and religions. In the context of the Okayama Art Summit, this reminded me of two things: the time you asked Hans Ulrich Obrist what the 'exhibition ritual' of the 21st century is, and your 2003 film, Streamside Day Follies, documenting a festival you created for a town north of New York. How might the idea of inventing a tradition or creating a celebration relate to the Okayama Art Summit? Do you see this exhibition as a ritual?

PHStreamside Day Follies was an annual ritual; a self-generating, modifying ritual that returned every year in a format that was both the same and different. The snake has been the host of many myths and narratives. It is overloaded with many meanings and is therefore open to speculation. The title of the exhibition is not complete; there is a part of the sentence missing, as if half cut. Obviously, there is a certain form of potentiality and uncertainty in the snake's form.

I am more concerned with the different laws of attachment and how that works between different systems of thought or entities; for example, there is no human life without bacteria.

SBI was thinking about this in relation to the kind of global exhibition format that Okayama Art Summit is connected to as a triennial show, a format that is at once uniform, replicable, yet open—kind of like the figure of Annlee: a replicable, empty vessel, or shell, that goes back to your interest in worlds becoming corrupted and reformed as they move through space and time.

PHYes. I would say, when it is corrupted and can be modified, a thing can actually start to gain a certain form of self-presentation. I use the word, 'entity', in relation to a site—a situated living entity. An entity is something that is not really precise. It's not a compact object, in that way—it is something you cannot turn around but inhabit.

In order to gain autonomy, there has to be an indifference to whether you are here or not. It's interesting that seven artists used Artificial Intelligence in the exhibition, which was unplanned. Each work has its own capacity to either learn or keep growing or changing or reacting—to combine all the parameters.

SBHow does this adaptation relate to the way you considered the context of Okayama itself when it came to working with the Summit's exhibition frame?

PHWhen it comes to Okayama, or elsewhere, I try to evaluate the potentiality of a site. Actually, there are many facets or angles to your question. When it comes to the idea of the global exhibition and my role in producing one, personally, I saw an opportunity in Okayama to change my practice from within. It was a way to take another angle and share ideas with others. Maybe naively, I saw an opportunity to have different minds I appreciate being in one place and exchanging ideas.

It's not about dropping works in the way that modernist architecture did, but embedding them within the site—a site of possibilities, excess, and fiction—while maintaining a ground. That is why I often talk about porosity and works that have the ability to modify in reaction to the place and are not just parachuted in—there is a crossfade and a continuity between these features. I tried to think about the dramaturgy of the exhibition form and to find a naturalisation between the site and these features.

SBRight. You kind of created a Garden of Eden.

PHIf so, only in the sense of cellular automation, where a Garden of Eden is a configuration that has no predecessor. It has to do with emergence.

SBThe idea of emergence recalls Not Yet Titled (2019), a work of yours that you are showing in the exhibition, comprising a large standing LED screen transmitting images that seem suspended at the point of becoming legible: the activity of an fMRI scanner that tracked someone's brain activity and used a deep neural network to visualise this activity using images in its database.

PHI'm interested in the condition of apparition, outside language, be it historic, scientific, or cultural. It is an apparition that exists before constructed expression. This idea of machines visualising people's dreams or reading their minds is becoming less and less metaphorical. It is interesting as it bypasses the means of expression. It has to do with the formalisation of an imagination. Here it is a collective production of imagination between human and machine—an attempt to visualise imagination. This endless process of recognition of a mental image is now reacting to its environment through different sensors—one being facial recognition—and adding new images within its presentation.

I find it problematic to consider the exhibition format as a medium that has no quality, as if it's a neutral thing.

SBThere is a sense in this exhibition that you have created an imagination of the future that is both machine and man-made. In some ways, it feels like the viewer becomes the masked monkey in your film Untitled (Human Mask) (2011–2012): left to roam a dystopian post-apocalyptic landscape. This made me think about something that you said once in relation to your association with relational aesthetics: that people have often misunderstood your relationship to your audience.

PHI was associated at one point to the Relational Aesthetic, with a few other artists and placed under an umbrella, which is what I tried not to do here. I am not so interested in the human-human relation or interaction. I am more concerned with the different laws of attachment and how that works between different systems of thought or entities; for example, there is no human life without bacteria. Human thus becomes an unstable concept.

SBOr how a global exhibition can settle into place.

PHSettled in the sense that it becomes naturalised, even if it remains alien. Again, as a site of excess or fictions.

SBSpeaking of settling, in a 2004 conversation with Doug Aitken you seemed to have reached a certain level of fatigue with the art world; you said that you didn't want to move around anymore, that the art world's globalism was a capitalist fantasy.

PHMaybe I didn't take that question very seriously 15 years ago! [Laughs]

SBHow would you describe your relationship to the art world now?

PHWhen it comes to my own practice, the less, the better.

SBI'd like to end by asking two questions that you once posed to Hans Ulrich Obrist. First, why do you continue to do what you do?

PHThat's the problem in life: what you say becomes a boomerang! [Laughs] Why do I continue to do what I do? I have asked myself many times and I often doubt. I continue because I am a believer.

SBA believer in what?

PHIt has to do with the joy of witnessing moments, or weird situations of synchronicity, sometimes very brief, of something that we did not know could exist. It's about these moments in which I can experience something else than what is, or what I have learned to know; or through which I can escape the condition of knowledge to which I am attached. That we are attached to.

The reason I keep doing what I do lies between an accident and being in love with something, and to have, for a glance, a sense of otherness—an escape from the condition of entrapment, banality, constraints; consensual reality.

SBWhat would be a reason to stop?

PHA reason to stop? No! [Laughs] Okay: I can say that when the joy in accessing the unknown is broken.—[O]