Raquel Ormella

Raquel Ormella in front of Wealth for toil #1 (2014). Courtesy © the artist.

Raquel Ormella in front of Wealth for toil #1 (2014). Courtesy © the artist.

In Raquel Ormella's installation City without crows (2018), an animation shows a crow repeatedly launching itself at the bars of its cage, cawing and hitting its head again and again. Ormella says the film is about being in a pet market in Yogyakarta, where she saw a recently caught bird—she could tell because it hadn't yet learnt it couldn't escape. It would have been distressing for anyone to witness but Ormella, an avid birdwatcher, found she couldn't look away. In the end, she stood there so long that the stallholder, in an effort to calm the bird and get rid of Ormella, threw a sheet of plastic over the cage.

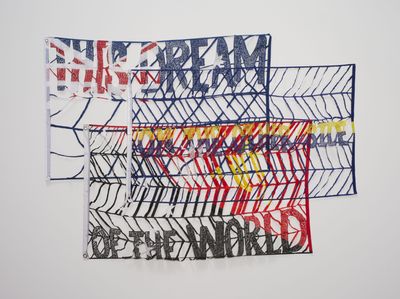

The animation occupies one of the back rooms in Ormella's 20-year survey exhibition I hope you get this, on view at Shepparton Art Museum (in the north of the state of Victoria, Australia) between 26 May and 12 August 2018, before it tours to five more regional Australian museums over the next two years. Ormella has covered a lot of territory in these two decades. She has sewn banners inspired by political events in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and made drawings on whiteboards using imagery associated with local environmental campaigns. She has also worked on symbols of Australian national identity. In Wealth for toil #1 (2014) she took up the promise offered in the Australian national anthem and turned it into a grand, glittering banner that reads, 'GOLDEN PROMISES'; and in Workers blues #1 (2016) she stitched together hi-vis and cotton fragments from the clothes of blue collar workers. In her 'Poetic Possibility' series (2012–2013), she moved onto the Australian flag, reconfiguring the fabric to open up a literal and figurative space to rethink what such a symbol could be.

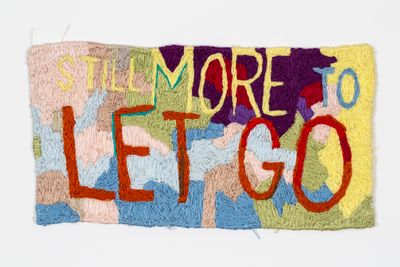

The survey exhibition also includes a recent work called All these small intensities (2017), a compilation of very small, intensely worked embroideries. They see her mining her own past, looking at the emotional resonances of certain colours and palettes—one faded grey stitching carries the text 'My father's work clothes'.

Many of these different bodies of work are united by the visibility of Ormella's labour, which is present in each tiny stitch, burned hole or pen stroke. City without crows operates differently. Sheets of paper are assembled along the wall nearby the animation—photocopies from Indonesian bird guides with post-it notes marking all the species seen in the market. This part of the work speaks of another kind of labour, and it accumulates and builds up slowly with each handwritten note.

The way City without crows is placed in the survey also shows how central birds are to Ormella's practice and her way of engaging with the world—from the ephemeral, performative element of birdwatching to her take on nationalism. Birds don't have much respect for the idea of borders either, as it turns out. But more than that, birds have become another sort of symbol for Ormella to take apart, one which relates to our broader relationship with animals and the natural world.

These days, exhibitions like An Incomplete History of Protest at the Whitney Museum of American Art (18 August 2017–27 August 2018) speak to the broad unease around the idea of political and protest art, and what it can achieve in the contemporary world. While Ormella's banners and flags have seen her cast as a political artist, she is less interested in pushing for specific change than she is in analysing the visual and spoken languages used in these sorts of conversations.

JOHow did you become socially engaged when you were younger?

ROI've noticed there are a lot of descriptions of my practice at the moment that combine the words 'art' and 'activism'. I do feel like I can't really wear that mantle anymore. Other people have taken that up. It's not that I don't think that I'm active; it's more what my work is really about reflecting on what activism is, and how that is manifested.

For example, City without crows (2018) is a work I made a few years ago when I was on a residency with Gertrude Contemporary's Independence Project in Yogyakarta alongside young environmental activists and scientists. The environmental movement in Indonesia is still developing—it's still in a nascent stage in terms of giving agency to the natural world and rethinking the dominant paradigm of human use of landscape and human use of animals. There are a lot of sad things and a lot of very destructive things that you see and it's a lot to do with economy and wealth. If you're much more concentrated on making a living, where does the natural world fit in? Where do you get the space to rethink that?

The work is about visiting the pet market in Yogyakarta in Indonesia where birds that are caught in the wild are traded in the pet market. I could not have made the work without being with people who have various ways of thinking about themselves as political subjects and have a very different political culture. It helped me think through and watch them think through what to do when somebody is trading a protected bird. You know that bird is on the brink of extinction, and yet it is being traded illegally. There are laws to back you up, but what do you do in that situation? How do you act? Do you send someone to prison?

There's my age, too. I remember what it felt like wanting to 'just go for it', and that kind of anger that you have in your twenties and your thirties. I'm going to turn 50 in six months' time. My energy is at a different point. I think for artists, when you get into this stage of your career, you start to mine your own past in a sense. You have a different relationship to your own history. That's been interesting in terms of putting the show together.

JOIt's an interesting time to be thinking about the questions around activism. There's so much going on, not only in the art world but in wider discourse. I'm thinking about the huge debates we've just had about Facebook algorithms and then I'm looking back at your banner works from the late 1990s wondering how they make sense in the world now?

ROThe text on the banners in 'I'm worried this will become a slogan' (1999–2009) come from newspaper articles from 1999 till about 2002. They were one or two lines of a personal story embedded in a political story and that was unusual—to have a news story embed personal actions in relation to a global event, whereas now that has become the mode of addressing news stories. It's often like social media and the 'I was there...', 'my view...', 'my personal view...'.

My decision at the time to include the first-person address was a response to a strong trend in documentary—and in post-conceptual practice—in terms of thinking about the artist framing themselves within the artwork. It's not like artists are looking at a situation and talking about that from a distance—they are actually seeing themselves within the frame of that artwork as well. So, they're trying to problematise their own position in relation to what it is that they're talking about. I think my work definitely draws on that tradition of institutional critique and post-conceptual practice.

JOI was thinking about the way labour and national identity are questioned in Wealth for toil #1 (2014)—'wealth for toil' being a passage from the lyrics of the Australian national anthem. The work's title is somewhat embodied in the labour that it required from yourself. What do you think about that work now, coming back to it after a couple of years?

ROI just want to make another one, but they take about three or four months. I think that's the other thing that comes through in the show. City without crows is a little bit different because the physical labour isn't as present.

JOYour survey covers some very different bodies of work, from the animations and photocopies in City without crows, to the textile banners and whiteboard drawings.

ROThere's a sense in which my practice is not connected via a medium or material approach. I move across things, but I would say the main actions, or the main motivations, that I work through are: textile work; sewing; drawing—as a key way of thinking and rethinking and representing the world—and photography, which is a big part of my research process but it's not really something I use as material or a medium for art.

I think the other thing is performance which has always been less apparent in terms of my career but which has always been very much alongside my research. So, the performance of the one-to-one conversation between the artist and someone outside the discourse of art that you're meeting—it could be birdwatching in Japan; or birdwatching in the middle of Indonesia; or photographing people to then deconstruct as a drawing ...

City without crows has been a performance work. I've been really thinking about how I present that performance work in this space. At the moment it's a bit like an exploded zine where there are all these photocopies pinned to the wall, compared to something like Wealth for toil #1, which is a four-month work of intense hand sewing and painting and labour. It's almost like there's no labour in City without crows. But there's an incredible amount of labour in there. It's emotionally-embedded thinking and a response to this question of extinction, and the witnessing of this crow hitting its head against the cage trying to escape.

So, they're not connected by medium. And in a sense, they're not really connected by theme either. I would say national identity and nationalism is something I've been working through, but also human relations to the natural world, environmentalism and birdwatching, which is obviously a key passion—so that's always appearing. But when you look at the show here I think what you can see in the front three rooms are three really different approaches to the textile work. And then the back three rooms involve different approaches to drawing and environmental thinking, as embedding oneself in a kind of deep thought about the more-than-human world.

JOYou have this ability to shed light on symbols and fragments of text that are politically or emotionally heavy, and then go through this symbolic and literal process of unpicking or unravelling their meanings. I wonder if, in doing that, there's a point at which it all comes apart, and it all becomes hopeless? Would you say that your labour comes in to balance that?

ROI think so. I'm not trying to hide how things are made. The photocopier is present, the stitching is present, and the substrate is present. The pleasure in looking is not about not knowing how it's made, it's about knowing how it's made and putting that into the meaning of the work.

But in terms of things coming apart, there is a way in which I work through something like the burning of the flag with incense sticks for works like Poetic possibility #1 (2012) and Return to the beginning (2013) or making the double-sided banners, like I'm worried this will become a slogan (Xanana Gusmao). There's a point at which I have to say to myself, stop. You could make another 50 of these, but when does that over-making become something which undoes the work itself?

I would like to make another Wealth for toil #1 if I had another four months where I could just do that, because it's so glittery. It's the bowerbird thing. Just looking at the metallic is very exciting. It's mesmerising. You just can't step back from it sometimes.

But I stopped making the banner works because I didn't want to be the 'banner girl'. Then I started working with the flag then the [then Australian Prime Minister] John Howard gave me the shits and so I didn't want to make another Australian flag. Then I started making the 'Poetic Possibility' works, about eight or nine years after I stopped making the other kinds of banner works. I needed to get hold of this flag symbol and rethink it without the weight of what it is. It was about stripping it completely back to something like New Constellation #1 (2013) or Return to the beginning (2013), which are the works in this show—where the flag is completely emptied out. But then where do you go, apart from the edge? The edge isn't actually very interesting.

JOBy asking more questions, you sidestep the whole question about the purpose of political art and whether it can ever achieve change.

ROYes. And I don't find being in that space suited for me. I teach and I spend a lot of time, creative energy, and 'communication energy', if you like, with people studying at university—mostly young people but also older people. To me that's a place that's really threatened. It's terrible what's happening with the caps introduced by the new higher education policy. In a sense, teaching and fronting up each day and being in a conversation with people about creative practice feels, not like a political action, but a good use of my energy.

JOSo, this refocusing of energies, is that what led to the new embroidery works? They're much smaller and seem more internally driven.

ROIt's partly that, but I won't say that I'm going to let go of the public. I started making an embroidery—it's not on display and I won't ever show it as an artwork because it's not really an artwork—when the Water Protectors at Standing Rock and the people there were being gassed and water cannoned in freezing conditions. I was watching that and thinking, oh the environmental activists in America just have it so tough. And if there are First Nations activists too, then doubly hard. They're just treated like terrorists because they're interrupting capital. So, I thought, I just need to do something now because when I'm looking at a stitching I have made I can remember the news, I can remember the podcast, the book or the music I was listening to at that time. I wanted to do something which was about marking that moment.

Then, that made me realise that I'm going through this process of packing things up, getting rid of stuff. We're probably going to leave Sydney and move to Canberra. I moved my studio to ANCA in Canberra two years ago and I moved the stuff out of the attic. But then I found all these threads that I'd had since I was six, and all these unfinished craft projects.

JOThey have a weight to them, don't they—all those unrealised dreams.

ROI also realised that I don't often finish things. I often start with a very big work and then, even as a kid, not necessarily finish it. Maybe I'm reading too much into that.

JOThat is hard to believe, looking at this exhibition!

ROBut you can't see what I imagined! I know it's funny. Chris McAuliffe, my colleague at the School of Art & Design at ANU [Australian National University], has said to me, 'nobody can see the things that you didn't do'. It's not about getting it so it's tight. It's about understanding when the material has enough, when it's got enough.

And if you're talking about something like responding to Standing Rock, your emotions at that moment—I imagine they're not going to be the same as in three months' time.

No. Also, that work was just the start of it. I basically just started stitching over a stitching I had done as a six-year-old. I didn't want to let it go, but I wanted to transform it so I could live with it. Then I just started sewing and I found I really enjoyed it, just the thoughts coming up and thinking about the colours. I'm a painter who won't allow herself to paint. I get really excited by colour, and I get really excited by colour in a material form. All these small intensities (2018) is about colour: trying to think through certain palettes and why I kept those colours.

JOSo, you're thinking about the emotional resonances and memories of these colours?

ROThe emotional resonances, and where I was. Certain colours were about my father's working clothes, because I was thinking about my father's migrant trajectory at the time I bought them for the original art school painting. Then I'd see certain colours lined up together in a readymade packet and I'd be like, that's such an interesting colour combination—I need to remember these colours, and so I'd just buy the packet of threads and then hold onto them for 12 years. And then it was like okay, use them or lose them. Of course now, I've got three or four times as much thread as I had when I started.—[O]