Rasheed Araeen

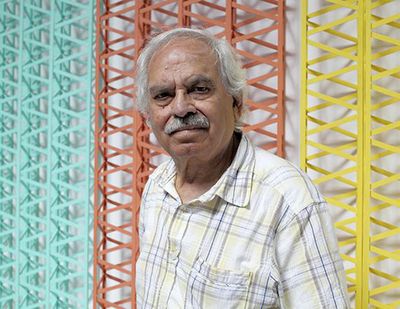

Rasheed Araeen photographed during the exhibition Rasheed Araeen: Before and After Minimalism at Sharjah Art Foundation, 2014. Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation

Rasheed Araeen photographed during the exhibition Rasheed Araeen: Before and After Minimalism at Sharjah Art Foundation, 2014. Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation

Rasheed Araeen should not need an introduction: he is one of the foremost pioneers of Minimalist sculpture in Britain. And yet, (with his first exhibition in Asia taking place now at Rossi & Rossi, Hong Kong), that there is a need to introduce Araeen refers to something that has driven at least part of this artist's 50-year career.

In 1987, Araeen established Third Text, the second incarnation of Black Phoenix (1978–1979), a magazine that responded to the institutional racism experienced by artists of the so-called peripheries—or those who existed outside of a predominately white, western-centric canon. As Araeen observed, those included in the history of Minimalism, such as Sol LeWitt, were struggling with Minimalism by the time he was confidently mastering its language.

To this end, that Araeen needs an introduction reveals how much catching up there is yet to do, as the art histories of the world continue to be re-written and expanded. Araeen ran Third Text until 2011, leaving behind an institution in its own right: a publication that today offers 'a critical analysis of contemporary art in the global field' and that was established as a direct action against a centralised narrative of visual culture.

As an artist, Araeen's career had two beginnings: in Karachi as a civil engineering student practicing (excellent) painting on the side, and again when the artist landed in the United Kingdom in 1964. It was in the U.K. in March, 1965 that Araeen saw The New Generation, a group exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery featuring many artists who had been students of Anthony Caro at Central Saint Martins, noting a turn away from Moore and Hepworth-esque figuration towards a Greenbergian form of modernist abstraction.

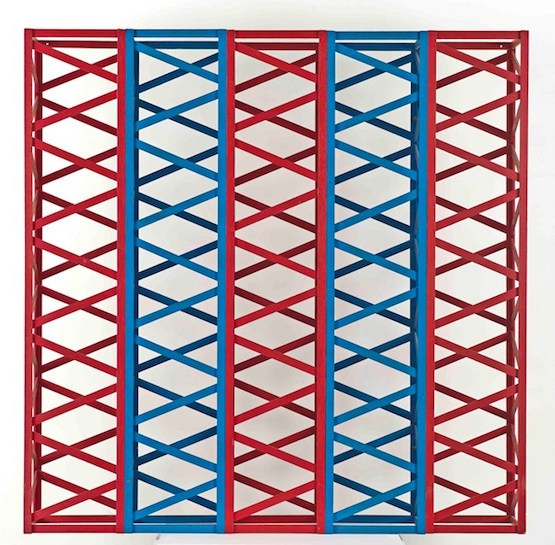

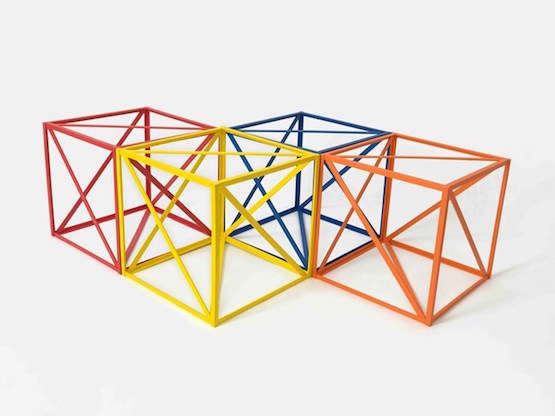

From early on, Araeen was enamoured by Caro's approach to sculpture. He was struck by the use of industrial materials in compositions focused on colour and form and started working with the structure of the lattice as a way to interrogate the Minimalist grid. He made cubes out of wooden strips painted different colours, and designed to be used modularly, and openly: a trademark style exemplified by Zero to Infinity, a work proposed in 1968, and realised in 2004 at 198 Gallery in London, and then re-shown as part of The Tanks: Art in Action at Tate Modern in 2012–2013. The work comprises 100 blue lattice cubes positioned in a gallery for an audience to move around. As Araeen told me in conversation in 2014, the idea behind the work was 'to go beyond this static geometry.' In breaking this barrier, he continued, 'you introduce a movement that is infinite.'

In 2014, the Sharjah Art Foundation staged an exhibition of works by Araeen. It was a long overdue look into the work of an artist who has never stopped thinking through the question of how art might become more public. But when I say public, I don't mean public in the singular sense of the word. Rather, Araeen is more concerned with how art might activate a social consciousness. This approach is perhaps best articulated in 'Chakras' (1969–1970), a series of performances, one of which Araeen staged in 1970 near his studio at St Katharine Docks in London. The performance was composed of Araeen inviting people to throw 16 fluorescent red discs into the water by the docks.

Araeen told me in conversation in 2014 that the work was ultimately about how one could deal with what one sees in the surrounding environment—in this case, the polluted docks; filled with rubbish and grossly neglected. As he explained, 'with Zero to Infinity and 'Chakras', the underlying idea is the same: to break symmetry. For example, in 'Chakras' . . . when you threw [the discs] onto the water, their symmetrical structure was broken and they created their own movement.'

SBYour exhibition at Rossi & Rossi in Hong Kong is called Going East. This is your first exhibition in China, and I'm curious how you feel your work might relate to this context?

RAWhen I showed my Minimalist work in London for the first time in 1970, the general response to it was that it was a form of Islamic art. Not only could I not accept this, but I had to struggle against this reading and understanding of my work.

In 1970, I did not know anything about Islamic art, nor was I interested in it. My interest was in Modernism, and this was formed in Karachi as a result of my experiences of everyday life there and the knowledge of the work of artists in Pakistan, particularly the work of Zubeida Agha and Shakir Ali who had spent some time in Europe and had returned to Pakistan soon after its creation as an independent country separated from India. Both these artists brought with them Western forms of Modernism, and with their work they became the pioneers of Modernism in Pakistan. There was nothing Islamic about their work, nor did we have any Islamic monuments in Karachi.

My introduction to Islamic art came in 1973, when Paul Keeler organised a show of Islamic arts at the ICA in London. I did then realise that the symmetry and seriality of my work was somewhat similar to the use of geometry in Islamic art. But even then I could not accept that my work had anything to do with Islamic art because there was no modern discourse, theoretical and historical, which would connect the modernity of my work with [the] Islamic tradition of geometric abstraction.

After 50 or so years I have now realised that my struggle against the dominant system for which I was the other who could not be part of the mainstream history of Modernism was somewhat futile, as I could not demolish the thick and high wall of Eurocentric art history. So, I began to look into the history of Islamic civilisation and its achievements in science and philosophy, which resulted in my writing in 2007–2008 about the importance of geometry in Islamic thinking, or its world view

At the same time, I also decided to publish Third Text from Karachi, which was founded as Third Text Asia in 2008. I also then established my studio in Karachi where I began to create works relating to the achievements of the great philosophers of the Muslim world; which in fact helped Europe to come out of its Dark Ages.

I can now reclaim my own Asian/Muslim identity, not by returning to my cultural roots but by placing my identity within the history which had been suppressed by the West, the very West which was awakened during the Renaissance with what it had received from the Islamic civilisation. With all this I can now say that I'm 'going East'.

SBWhat are the works you are showing in Hong Kong? You said this show is like a mini-version of the retrospective you staged at Sharjah in 2014, which presented works from your time as an engineering student in Karachi, to the three-dimensional works made of wooden lattice grilles, which have been a characteristic element within your practice.

RAThe show comprises samples from different periods of my work. For some time now I have been re-making those Minimalist works which I had destroyed in the 1970s, but there were also the works which were not completed or developed further.

Besides the reconstructions of the destroyed works, I'm also now developing further the ideas which were abandoned, creating new works in this respect. This show also includes two works from the series produced in Karachi since 2010, which can be considered as geometrically constructed calligraphy, based on the names of [the] six most important philosophers of the Golden Age of Muslim civilisation (800–1300). So, it is a mixed show.

SBAs an extension to the previous question, I wonder how you feel when you look back on your life's work? What do you see when you look at the works you made in Karachi, and the works you are making now?

RAThe works I made in Karachi before I came to Britain in 1964 were kept hidden in my house in Karachi and were not exposed for the last 50 or so years. Even people in Karachi or [anywhere in] Pakistan did not know anything about these works. So, after I established my studio in Karachi in 2009 I brought out these works and displayed them on the walls of my studio.

This not only surprised the people of Karachi who saw these works for the first time, but they also made me think about their relationship with what I did in London. I then realised that the roots of my work in London were actually there in Karachi. So whatever I now do is somewhat the continuity of the early works.

SBI'm thinking about the series of paintings you created recently, which use Arabic text as a frame through which to explore geometric abstraction. Would you talk about these works? How did you conceive of them, how did you choose the words that provide the grid for these abstract paintings, and how do they expand on your practice (in terms of art-making) as a whole?

RAThese new works, which use a sort of calligraphy, are based on the names of the most important philosophers of the Islamic civilisation. The tradition of Muslim/Arab calligraphy is religious, comprising either verses from the Qur'an or the names of Allah and the Prophet Muhammad; which is actually achieved by a technique of writing on paper even when paints on canvas are used now.

My attempt has been to first secularise this tradition by painting the names of the philosophers, rather than writing their names as most artists from the Muslim/Arab world still do, so as to achieve what is pictorial and abstract, to the point that you cannot easily deduce or read the names.

SBOf course, your work is very much about the decentring of canons and hierarchies within the art world—when it comes to your use of the wooden lattice grilles in your work, for instance, one of your best known interventions is Zero to Infinity.

Conceived in 1968 under the title Biostructural Play, the work was only realised in 2004, and then acquired in 2007 and shown in 2012–2013 by the Tate Modern.

This interactive piece can consist of up to 100 lattice cubes presented in a space, free for viewers to move around at will. We have spoken about this work before, and how it tried to explore a kind of horizontality that was, perhaps, very much a part of the discourses at the time of the work's original conception. I wonder if you would talk about this approach to social complexity in your work?

RAIn 1965, I realised an idea of symmetrically constructed sculpture I did this intuitively without much thinking about 'decentring' the canons of art history. It was only some time later when I came to know about New York Minimalism—that it was a historical movement—I became aware also of my place in art history.

This was unacceptable to the Eurocentric art establishment, and my work has remained outside the narratives of mainstream art history. Although Tate did recognise in 2007 that I was a pioneer of Minimalist sculpture in Britain, this has made no difference to the Eurocentric art history because it cannot allow itself to be confronted and changed.

It is also important to point out that there was little knowledge of Minimalism in the U.K. until New York Minimalism arrived in London in 1969, and then it was the only New York works that were promoted by the British art establishment, with the implication that there was no British Minimalism. However, before we knew about the New York Minimalism, I had already gone beyond Minimalism.

In 1968, I thought of dismantling the rigid, static structure of Minimalism, with public participation, and called it Biostructural Play—later changed to Zero to Infinity. This represented a radical conceptual shift in my work, from individually conceived and constructed works to the works which were made by the public. The role of the artist in this respect was only to initiate an idea, which when taken up by the public would become a work of art, with a shift of creativity from the individual to the collective.

SBI also wonder if you would talk about how this relates to abstraction not as a formal approach, but as a philosophical one?

RAThis is a very difficult and complicated question, and its answer is within what has been suppressed by the emergence of the West's world power about 600 or so years ago and its imposition on the world of its own tradition of art. The basis of this tradition lies in the Greek-Roman iconography, by which the world is perceived and constructed through the visibility of the divine, then taken up by Christianity.

It was only in the 20th century that European artists realised the limitation of this tradition and turned to abstraction. But this shift from the realism of iconography to an abstraction was already achieved by the Islamic civilisation almost a thousand years ago. It was in fact a philosophical shift, from the notion of the divine as the visible being and its representation through the human form to what is invisible and could not be represented by any (living) form; which in fact resulted in the Islamic world view based on the primacy of geometry.

SBYou have had a very long and dynamic career, and in recent years, you have finally been recognised as one of the key artists of the 20th century; one of the founding fathers of Minimalism, who developed in isolation from the movement in the United States and the United Kingdom.

How do you feel about this recognition? In other words, do you feel the struggles you engaged with in the sixties, seventies and eighties have produced results today? Do you think the art world has become a more culturally horizontal space in which other histories have been given equal footing with the Western canon?

RAYes, I did have a very long, hard, and difficult career. But it was not really a career but a pursuit of an idea, which has not ended. Whatever I have achieved is not really the achievement of a successful artist, but the one who might have produced a body of ideas useful to humanity.

The present recognition of my achievement did not come from Britain but from a country in the Gulf; it was Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi who when showed my work in Sharjah that I got the break and then the world began to see what I had done and achieved.

The art world has now changed through its own dynamic, becoming global and allowing artists from all over the world to be part of it. This is merely an art market phenomenon, in which though Western art institutions are also involved. But this has made no difference to the constructions and narratives of the mainstream history of Modern art, which continues to remain, as I have said before, the exclusive domain of the privileged white artists from Western Europe and North America.

SBYou have been such an active critic of racism, discrimination and white privilege in Western art discourses. In the seventies and eighties, you worked tirelessly to offer a platform for artists of non-Western origins to show work, founding Black Phoenix in 1978, and later Third Text in 1987.

RAYes I did work very hard, not only for myself because I realised that I wasn't the only one who had suffered from the West's attitude towards those who were considered to be different from the artists of racially European origins; particularly artists of Asian and African origins who were seen to be outside mainstream Modernism and its history.

These artists are now accepted and in fact celebrated as part of the globalised art market, and within its biennials and festivals, but only outside the mainstream art history, which still remains the exclusive privilege of white artists.

SBI'd like to talk about the Mediterranea project you have been working on for some time. Why has the Mediterranean been such a space of interest for you? How do you relate to it as a Pakistan-born British artist?

RAThe idea of Mediterranea came to me suddenly and intuitively when I was in Karachi 15 years ago; it was a sort of brain storm which could not be then explained rationally. I did though then write down its basic concept which was to create a union of all the Mediterranean countries. The Mediterranean comprises not only some countries of Europe, Asia, and Africa, but a crossroad for all the three continents.

When it allowed the unrestricted movement of all people carrying ideas with them and exchanging them, it created what is claimed by the West as its own civilisation. But this civilisation was and is the creation of the three continents and it should be claimed by all of them. This would happen only when there is again the free flow of people across the Mediterranean. The project of Mediterranea, which I developed subsequently, comprises many art projects through which its people will be able to able to come together again and create ideas and things collectively.

Although this project was conceived in Pakistan, it shows that human imagination cannot be trapped within a nation and its culture. It can in fact transcend their boundaries and look at the world and bring its people together; and then the energy of all the peoples together with their collective creativity and productivity can and will change the world for a better future.—[O]