Rashid Johnson: Creating Agency Through Collision

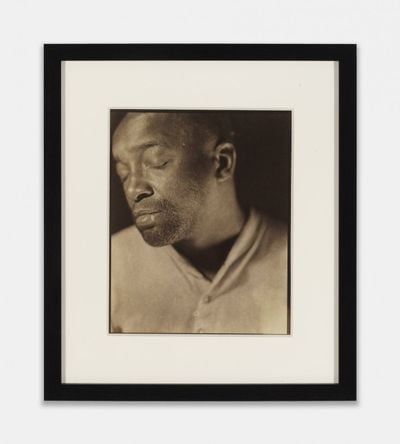

Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kendall Mills.

Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kendall Mills.

Rashid Johnson's investigations of themes related to class, race, and identity first found expression in conceptual photography, before spanning installation, film, and sculpture.

Born in Chicago in 1977, Johnson became known for countering the dominant modes of representation of his time, which found articulation in Freestyle at The Studio Museum, Harlem (28 April–24 June 2001), where curator Thelma Golden gathered 28 artists working outside the framework of 'Black art' to contend with its actualities and nuances.

Johnson, then aged 24 and having recently graduated from Columbia College, was the youngest of the group. His contribution, the 'Seeing in the Dark' series (1998–1999), shows portraits of homeless African-American men. Depicting each individual with dignity, every photograph possesses the name of the subject as its title.

As others transitioned to digital photography, Johnson's images were made using traditional processes such as Van Dyke Brown printing, a 19th-century image-making technique. Johnson's work has since spanned a range of mediums, with influences as diverse as Afrofuturism—more specifically the music of Sun Ra—literature, philosophy, mysticism, and African-American history.

In 2012, Johnson became the 8th recipient of the High Museum's Driskell Prize celebrating contributions to African-American art and scholarship. The same year, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago held his first museum retrospective, Message to Our Folks (14 April–5 August 2012), which travelled to Miami, Atlanta, and Saint Louis.

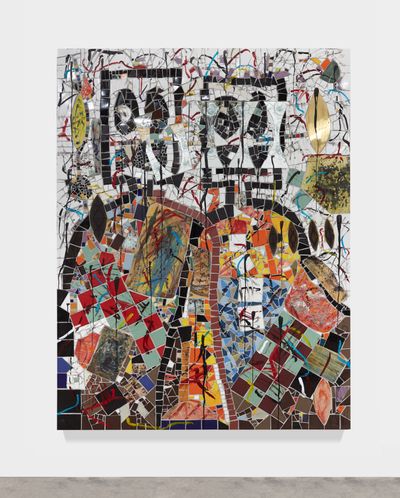

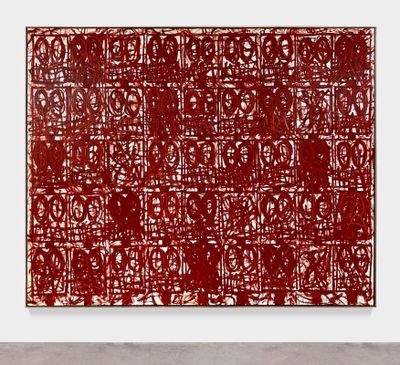

Contending with anxiety and fragmentation, Johnson's later exhibition Waves at Hauser & Wirth in London (6 October–23 December 2020) featured paintings and ceramic mosaic works in which spiralling red lines and broken ceramic tiles reflect on the political turmoil marking the United States.

As people marched in the street protesting police brutality, Johnson's 2020 film The Hikers explored the ways the Black body is expected to move through space. Shot on a Colorado mountain peak, two young dancers from the Martha Graham Dance company wearing Johnson's 'Anxious Men' masks cross paths as they perform a pas de deux.

Currently showing at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, in What Is Left Unspoken, Love (25 March–14 August 2022), Johnson reflects on meeting the unknown with love in The Hikers, which also informed a travelling exhibition of the same name, shown at the Aspen Art Museum (4 July–3 November 2019), before heading to Museo Tamayo in Mexico City (27 July–10 November 2019), and Hauser & Wirth in New York (12 November–25 January 2020).

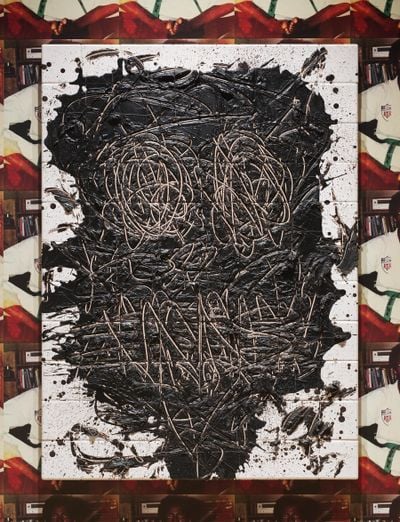

Presented alongside the video, ceramic mosaic works, and paintings, the bronze-patinated sculpture Untitled Bronze Head (2019) recalls its larger sibling Antoine's Organ (2016)—a massive plant ecosystem inside steel scaffolding with monitor screens, ornate rugs, and a piano, shown at Art Basel in 2018 (14–17 June), which included books like Richard Wright's Native Son (1940).

Johnson adapted Native Son in 2019, retelling the story of a young Bigger Thomas who is brought into a world of affluence and charged for the murder of a white woman's death. Screened on HBO the same year, this first attempt at commercial film direction followed previous efforts to reconfigure theatrical productions like Amiri Baraka's Dutchman (1964) in 2013.

In the following conversation, Johnson speaks with High Museum of Art curator Michael Rooks about the connections between sculpture and film, significant cultural references in his work, the making of The Hikers, and the personal and collective aspects that motivate his practice.

— Ocula Magazine

MRI thought we'd start with works you made prior to The Hikers. Although you may be best known for your sculptural installation and photography, filmmaking has been integral to your work for at least a decade.

Your films include Sweet, Sweet Runner (2010), which was shot in 16-millimetre film, and The New Black Yoga (2011)—both of which were included in your museum retrospective Message to Our Folks—the remake of Native Son, and of course, Black and Blue (2021).

RJOne of my goals is to create contradictory opportunities for exploration and the explosive agency born from those conjured collisions.

MRWhen I saw Native Son for the first time, I was struck by the formal similarity between the film and your monumental installation Antoine's Organ. Both have layers of references to art history, literature, and philosophy and serve as scaffolds for the entirety of your oeuvre.

Do you see connections between sculpture and film in your work?

RJI do see quite a bit of similarity between how I approach film and sculpture. I would add my interest in collage, music, and as you mention, how literature functions as a scaffold for these mediums to come together and contradict one another. As my friend Robert Longo once said, it's about collision.

At this point, I think we have become so invested in this idea of integration within the arts—this ambition to see art practices leave their singular intention and be joined in some ceremonious and harmonic engagement.

My work doesn't ask for that, and it doesn't attempt to bring that to fruition. One of my goals is to create contradictory opportunities for exploration and the explosive agency born from those conjured collisions.

Native Son is a good reference point to discuss this, as it takes as its launch pad Native Son by Richard Wright, which has a quite sorted, complicated, rigorous, inventive, and important history both in African-American communities, and the field of literature.

Wright functions, in some sense, as an existentialist, but he's rarely spoken of in those terms. He has a relationship to Camus and expatriates in Paris at one point, as well as the folks to whom existentialist and critical thought are often framed.

So, Wright is this character who expands beyond his own origin story, or what and how we have explored his origin story. It brings into collision the work of James Baldwin, who, at one stage, writes a piece that contradicts the concerns in Wright's novel and suggests that it's a protest novel lacking sophistication in its depiction of the complexity of the Black male and the conditions to which he's exposed.

So that becomes part of this conversation. I was then able to bring in a woman named Suzan-Lori Parks—an important, award-winning playwright who studied with James Baldwin. We were able to concoct a contemporary telling of Wright's story with consideration for Baldwin's concerns.

So that real-world action leads into locations in Chicago that were integral to my development as an artist and a person, which are familiar from my youth through my graduate experience.

I've known Michael for over 20 years, in the arts. You've been an incredible supporter of my work and thinking, so some of this will be quite familiar to you. It's like the real world meets the literary world, meets invention, meets re-invention, meets structure, to use a word you used earlier, and is high functioning for this conversation—it's about that armature.

MRCollision is a great word to use. Especially when I think about the opening sequence of Native Son. As you were alluding, Wright is still to some who Kara Walker is to others; he's not James Baldwin and he's not Ralph Ellison.

RJAbsolutely.

MRIt's not hard to see why writers like Ellison and Baldwin resisted Wright and this existential vision of Black experience, but that was true to his own history of deprivation when he wrote this book.

At the start of the film, the character Biggers places his father's handgun on top of a copy of Ellison's Invisible Man (1952). What should this detail tell us about the narrative? I mean, it is literally like a collision.

RJIt is. It really starts us off with the understanding that I know quite a bit about the tools that I'm employing. That I'm aware of Ellison's and Baldwin's engagement with a person like Wright and their frustration with him, as Wright was almost this paternal character in Black literary circles.

So, in a sense, it was their opportunity, or Baldwin's in particular, to attack his father, or call into question his wisdom, which is fascinating. And then the positioning of this weapon on top of the work by Ellison.

As you may recall, Ashton Sanders, who's playing Bigger, coats his hands in shea butter in a disturbing fashion, on top of several rings. The character has been recast as a punk, which is an unexpected position for a Black character, or an unfamiliar telling of how a Black youth is imagined in the world.

He takes on the cloaking and costuming of someone who is invested in a music genre that is incredibly radical, individual, and complicated, that isn't hip-hop. A music that has more history with white radical culture than Black radical thinking.

Even though you could argue that Black radical thinking has influenced and been incredibly prescient to the developmentof the punk genre. You have all these unexpected positions being established quite early in the film, which give you a sense of the signifiers and the loaded algorithm of tools that inform how the story comes to life.

MRIn one sequence, Wright's book Native Son is on the bookshelf. I had to replay it a couple of times in order to see it.

RJThere are quite a few easter eggs throughout the film, whether in my work, references to Wright, to other texts, or art history and contemporary art histories with the inclusion of other artists—Henry Taylor, Sam Gilliam, Glenn Ligon; all these opportunities.

MRWe hear Bigger quote W.E.B. Du Bois' The Souls of Black Folk (1903) in Native Son, suggesting Du Bois' sociological thesis is as relevant today as it was almost 150 years ago. This quote really sums it up: 'Brand new game, same old shit.' Almost like a warning of a no-win situation.

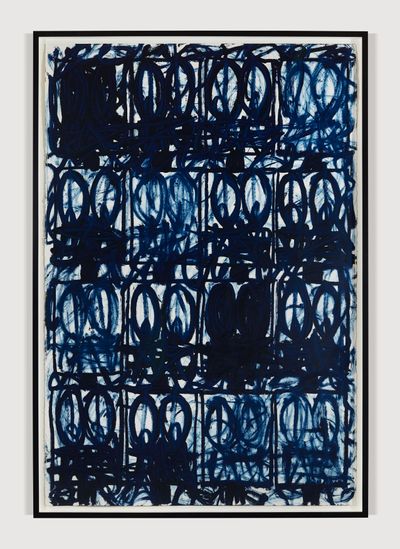

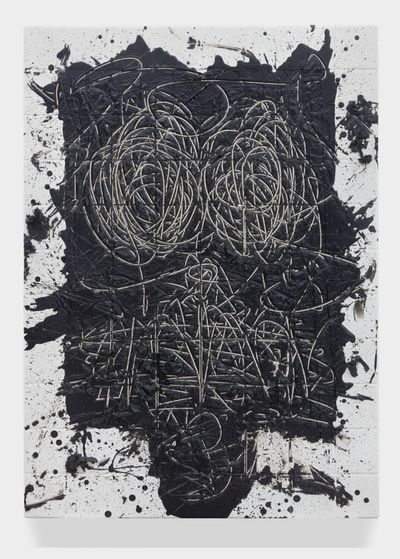

RJIt's one of those easter eggs. And for anyone who was familiar with my work before seeing the film, one of my 'Anxious Men' paintings (2015–2021) is hovering behind Bigger, almost like a warning as he goes into this home. However well-meaning these folks are, they are producing a scenario to which Bigger is unlikely to succeed.

How I approached this film was that I wanted to make a picture devoid of tragic depictions of any particular group. The white folks in the film are all well-meaning; there may be a bit of clumsiness, but you know that is just the circumstances of their engagement with Bigger, and the Black folks aren't ill-meaning, either.

If you create evil characters, it gives audiences an opportunity not to see themselves as part of the critical problem because they can relieve themselves of responsibility as someone who is better than this complicated and dark character that's been produced.

Everyone is invested in moving forward and making the world no more complicated for one another, yet something incredibly tragic still happens. The question then arises, what produced this problem if it wasn't conjured by individuals?

Often, films that intend to explore more complex issues around racial integration and entanglement posit an evil character. In the film Hidden Figures (2016), for example, there were Black women scientists who helped NASA develop the rocket, and this white antagonist who refuses to allow them to use a bathroom.

So, there's this evil character. If you create evil characters, it gives audiences an opportunity not to see themselves as part of the critical problem because they can relieve themselves of responsibility as someone who is better than this complicated and dark character that's been produced.

So, one of the main goals of this film was to never give anyone that opportunity and make everyone somewhat good. This way, when something horrible happens, it makes you examine the institutional concerns that go beyond individual engagement.

These concerns are inherent to the condition of these folks' engagement, which is also one of the reasons why this film generates new ways of examining old themes.

MRThat trope of having a violent character taking the responsibility off our shoulders, is, in a way, offered to Bigger in the film when he's listening to Beethoven's 9th.

You've got to believe that this an allusion to A Clockwork Orange (1971) in which Beethoven's 9th is a trigger for Malcolm McDowell's violence. But in this case, you see the character going into this beautiful, poetic enjoyment of this great artwork.

RJHe falls in love, and again, it's one of those almost contradictory positions, or one that creates unexpected dichotomies or collisions. We've produced a Black character in an unexpected body, with unexpected costuming, reference points, as with his relationship to punk music, but he's also interested and invested in classical music, which takes us to a place that we don't expect.

The character's inability to be pigeonholed and the fluidity to which he is exposing us is something I hoped would better illustrate who I am and know a lot of my friends to be, which are complicated people with unexpected ambitions, histories, concerns, and ways of seeing the world.

MRNow's a good moment to discuss Antoine's Organ, a work featured in the New Museum's exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America in 2021—the great Okwui Enwezor's last exhibition.

Two things are relevant to our conversation. First, there's a copy of Soren Kierkegaard's book The Concept of Anxiety (1844), and then, the title of your installation, which I'm assuming refers to Antoine Baldwin, whose piano is in the centre of the piece, and who composed the score for The Hikers.

Could we talk about anxiety as a subject? You first tackled this in The Drawing Center exhibition Anxious Men in 2015, which had its own soundtrack by Melvin Van Peebles. The presence of anxiety in Antoine's Organ seems to represent continuity in your recent work. While providing a conceptual scaffold, the theme of anxiety also belongs to this continuity of ideas and images that cross media and platforms.

RJYou've hit on a lot of micro-details that spin into the macro-opportunity I'm trying to present in the work. There have been times when the work has been suggested to be opaque, but I really find it to be the opposite.

I leave everything out to be examined and to your point, Kierkegaard's book on anxiety walks you through a lot of the antecedent and critical concerns I was having, and then the actual practical concerns I continue to have around how to navigate a world that's quite complicated.

When I was 19, I flew to Senegal, West Africa, where I was able to visit the home of the scholar, writer, and thinker, W.E.B. Du Bois. While visiting the home where Du Bois lived his final years, I discovered several texts by Kierkegaard.

Most of them were in German, and much of German philosophy was late to be translated as a lot of terms and positions taken were quite difficult, so the translations were important—Du Bois learned German at the end of his life to translate Kierkegaard's work himself.

The seminal text by Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, is also included in the work. I've used it quite a bit to think about how we conjure unexpected groupings that people may think are desperate in certain senses, but are not.

I'm also the owner of an older copy of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). Its previous owner was the 12-year-old LeRoi Jones, who then becomes Amiri Baraka. And this is the story of literature. The story of art. This is a historical understanding of the world and the ground on which we stand.

Our teachers are not necessarily the people we expect. LeRoi Jones at 11 or 12 years old is reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Whether he rejects, accepts, embraces, is disturbed by, or learns from this text is neither here, nor there.

His exposure is central to it, and so these ideas—and again, to get into the thematic of scaffolding, antecedent, and collision—are all one large rhizomic vein, and we're all on the road with any number of opportunities for exposure and engagement.

I'm learning, exploring—and in a sculpture like this, creating a framework and a brain; a place to put ideas and concerns to stage these growing collisions.

I think anxiety is an opportunity to speak about the wholeness of concern, to think about fear, and personalise these positions.

MRIs it fair to say that one aspect of how anxiety functions in your work is not as a representation of racism per se, but the evil in a society that creates conditions in which people who don't suffer from injustice seem incapable of caring about those who do?

RJI appreciate that interpretation. I think anxiety is an opportunity to speak about the wholeness of concern, to think about fear, and personalise these positions. Because often, when we try to describe the conditions of our experience to another, it can be hard to translate.

It can be hard to be the victim of those positions, and to feel like you are the perpetrator. To explore our personal engagement and turn into that more natal position people find comfort in.

I talk about something that is broad, and that broadness is exemplified by discussing anxiety, which most of us are familiar with. As such, we can position ourselves to consider with empathy how to engage the critical, emotional, and personal concerns that may not belong to us, but those adjacent to us.

That's how I unpack the position. It's a more thoughtful and sincere way of saying, here are these things—place them in this bucket, take them out, unpack them, and understand your relationship to them. Ideally, it allows for an opportunity to see yourself in my work and the critical concerns presented.

MRMoving on to The Hikers. Could you walk us through the narrative arc of the film?

RJI'll start with the context. I was asked to be a resident at the Aspen Art Museum in 2018. I'd spent quite a bit of time there before and really loved the mountains, which I had come to appreciate in a way that I had never expected as a boy from the Midwest.

I remember wondering what I would do in Aspen during this residency. On my first visits, I took a hike, which was not uncommon for me there, and noticed that I'd never seen another person of colour on a hike before that I hadn't brought with me.

That was interesting—wondering and thinking about the Black body in space, which has been something in my work for some time. Thinking about commonality, love, and unexpected engagements, I conjured this story of a man moving up the mountain, who confronted someone he didn't expect to see. The kind of platonic love that was born of that, which, for many communities, is quite familiar.

When I see a Black person in an unexpected place, there's always this moment. And I don't think it's exclusive to Black and Brown communities. Anyone who sees someone they don't expect in a condition or space has this existential moment, wondering whether they're looking at themselves, in a sense.

MRI've felt the same thing in situations where I've discovered another gay person in a room—where there's discomfort, and suddenly, this person provides comfort and joy.

RJAbsolutely. So, this film really speaks to those experiences, it takes them into this different context and becomes this balletic story choreographed by a woman named Claudia Schreier, who is fantastic and brilliant, and helped me bring this to life with a couple of dancers.

Lloyd Knight, who is brilliant and one of the principals at the Martha Graham Dance Company in New York, and another young man, Derek Brockington—an incredible talent who was in the Dance Theatre of Harlem. One is ascending in the film, the other is descending, and they have this moment of entanglement.

MRThere is this one still from Native Son that conveys an incredible feeling of anxiety when a job offer creates a violent situation for Bigger. While Bigger is interviewing for the job with this family as a driver, we see behind him one of your 'Anxious Men' paintings, which is sort of a self-portrait.

RJThat's correct.

MRCan you tell us about the history of this series and how it relates to notions of Blackness in The Hikers?

RJThis series is a complicated one for me, in that my work, my background, was really centred in critical, and often academic concerns in art and art history. I didn't necessarily aspire to make work that would suggest the specifics of our times early on.

My works have evolved to become wholly invested in gesture and the prescience of exploring the 'now' space, bringing these autobiographical concerns into how we navigate the world. So, this body of work is born from many personal transitions, one being fatherhood.

My son was quite young at the time, and trying to figure out how to teach someone to explore complex conditions is just so complicated. We've all become so thick-skinned in our experiences.

I really wanted these characters to have an opportunity to love one another in ways that we couldn't have predicted, however foolish that may sound.

We have so much knowledge, so much familiarity. But when you're exposed to a person who does not have those scars and isn't necessarily ready, or doesn't know how to experience those things, and you're forced to prepare them.

A lot of my anxiety at that moment was centred around this. I had stopped drinking, so there was this kind of autobiographical examination of my own sobriety and what the world would look like without the goggles I wore to move through it.

It's funny, I ran into you, Michael, once at the Russian Turkish bathhouse in Chicago, which is a place I would go to when I was in graduate school, and continued to go to. It's a place where you sit in a schvitz and sweat to let out what you brought in.

I would go to the Russian Turkish bathhouse, read Kierkegaard, Derrida's The Gift of Death (1992), Félix Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus (1980)—taking in all this critical, complicated language.

Just a quick anecdote—the first time I went to that Russian Turkish bathhouse, where I saw you, and this was 20 or so years ago, I was a little bit broken. My friend told me I needed to go and sweat out my anxiety.

The first person I see as I walk in the room is Jesse Jackson. He's butt naked. He looks at me and he offers me a Nehi orange soda, for anyone who remembers the Nehi orange soda. I remember thinking, where the hell am I? I'm in this basement with Jesse... And I started going there almost every day.

It was this place to relieve the stress building up around grad school and other things I was experiencing at the time. The backdrop in that space was this white tile.

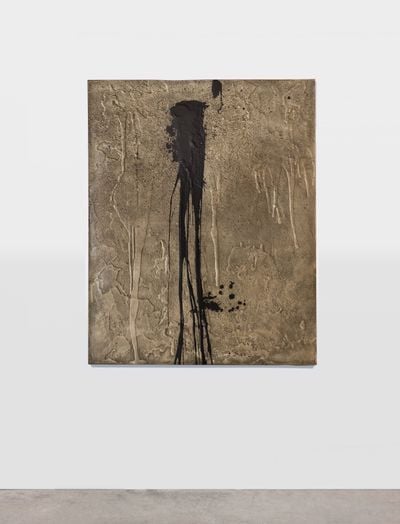

As I moved to New York and started thinking about my relationship to anxiety and other things I was experiencing, I found this to be a space of catharsis. I started to build these characters using black soap and wax on their surfaces, as self-portraits looking at a world that was increasingly complicated.

The murder of Mike Brown happened around the time I made these works and some of the other references, both to sobriety and fatherhood, all came together to make me think, I need to depict this. I need to illustrate this.

When I showed them for the first time, several people from the audience looked at them and said, 'That's me,' and my first instinct was, 'No, that's me.' It was an opportunity to illustrate something that felt more collective rather than just a personal concern. From there, the body of work really expanded, I felt like I was a voice for 'us' more than a voice exclusively for myself.

MRThey do have this kind of 'every man' quality to them. I've had my own shields for anxiety, be they alcohol, tobacco, or humour. It takes a lot of pressure off.

RJAnd I've used them all.

MRReturning to Native Son, both the book and your film serve as parables for the condition of being physically and psychologically trapped within the confines of American racism—a kind of prison without bars.

In the first 30 seconds of The Hikers, there is drumming, and then this moment when the two hikers approach each other in a swaggering bravado. Is this a conception of the psychological condition of being trapped in this system with your shields up?

RJThat's a really interesting way of seeing it. I had a few very specific instructions for Claudia as we started to imagine how we wanted the dancers to move through space, and one thought was that I wanted them to move as if they were completely unwitnessed.

So, imagining the body—in particular, the Black body—moving unmolested, without concern for certain kinds of witnessing, and the clumsiness that could be born out of that. We've always and still sexualise the Black body or imagine it with great rhythmic grace, or athletic feet.

We imagine it as being quite dynamic and capable, so I wanted to see how it felt for it to move with a sense of entangled and complicated rhythm. The characters move through and you see their bodies speaking a language that feels unfamiliar.

Claudia helped me bring that to life when I wasn't sure what I was looking for, but to your point about the framework of racism being the boundary to which a work like this lives, I would push back against that a bit and say that it lives within the framework of love and the possibilities of love.

If you can root for someone you've never met, for whatever reason that is—a shared characteristic, a shared aesthetic, then you're capable of love, right?

I really wanted these characters to have an opportunity to love one another in ways that we couldn't have predicted, however foolish that may sound. That was one of the big goals of this film.

MRWhen I saw the film at the Istanbul Biennial, I was the only one in the space and it was so wonderful.

In the critical moment when they meet, this platonic love blossoms and suddenly, the awkwardness you describe becomes a beautiful pas-de-deux ballet. They not only see each other in themselves, but they become—

RJConjoined.

MRIt reminds me of the Parable of the Good Samaritan, which Martin Luther King retells in Strength to Love (1963), in which two travellers are going up and down the road from Jerusalem to Jericho.

RJGood reference. Absolutely!

MRCollaborations are not easy and often far more complex and time-consuming than individual projects, and you had a lot of collaborators in the film. The music was composed by Antoine Baldwin; the choreographer, Claudia Schreier—who is also the choreographer-in-residence at the Atlanta Ballet—the dancers, and the film crew.

How do you find yourself managing such collaborations? Do they work well?

RJNo, not at all. It's quite astute. I think collaboration is important in understanding how something like this comes to fruition. I say this because I've joked in the past that artists are oftentimes not the best directors and collaborators, because we are often praised for individual thought.

We are given agency to live in our egos, to explore, discuss, and imagine our own ways of seeing the world. I've joked that curators would make far better filmmakers because they're really invested in dealing with lots of different egos and constantly.

As a director and a collaborator in a project like this, it's about navigating those egos and giving everyone the space to sing, flourish, and do what they do best. It was a real learning curve for me to not put my own concerns at the centre. It continues to be.

These collaborations have added to my interest in creating vehicles for folks outside myself. I'm super capable of creating vehicles for myself in the form of painting, sculpture, and to some degree, filmmaking, but I'm equally interested in creating opportunities to amplify the voice of others.

It's incredibly rewarding for me, and I can have that dichotomy; I don't have to be only someone who cherishes, examines, and tries to find space for themselves in the world—I can do both things.

Often, we're told that we can't, but if there's anything that I can give the folks who have stuck with us this long is that you don't have to be just one thing. If you are, you're doing it wrong. —[O]