Rayyane Tabet

in partnership with the 21st Biennale of Sydney

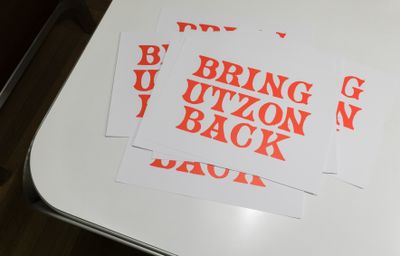

Rayyane Tabet, Dear Mr. Utzon (2018). Performance, podcast, 45 mins, reproduced 'Bring Utzon Back' leaflets. Installation view: 21st Biennale of Sydney, the Sydney Opera House, Sydney (16 March–11 June 2018). Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg and Beirut. Photo: silversalt photography.

Rayyane Tabet, Dear Mr. Utzon (2018). Performance, podcast, 45 mins, reproduced 'Bring Utzon Back' leaflets. Installation view: 21st Biennale of Sydney, the Sydney Opera House, Sydney (16 March–11 June 2018). Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg and Beirut. Photo: silversalt photography.

Beirut-based artist Rayyane Tabet's practice exists at the intersection of storytelling, sculpture and architecture. Here, the physical material—be it found architectural objects or material drawn from personal archives—is revealed to contain unresolved histories or buried narratives that are then exposed through the act of storytelling.

Heavily influenced by his training in architecture and sculpture, Tabet's artistic process is driven by an inquiry into how physical materials can be positioned within a more fluid understanding of history, in turn highlighting the personal and the emotional within the formal and the material. In Tabet's words, 'the question for me has always been driven by how one can find humanity—something more emotional—within the formal gestures of architecture and sculpture.' Tabet's sculptural installations are often large in scale and laborious to produce, using architectural artefacts from his native Beirut or excavating materials that represent the subject of his inquiry—as with his work Steel Rings (2013–ongoing), which saw the artist construct hundreds of steel rings to reflect the fragmented history of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline. Beyond merely representing the arduous process involved in their production, the works invite a reflection on the political conditions in which the artist operates, not least owing to the violence occurring across the Middle East region and beyond.

For his most recent intervention, Dear Mr Utzon (2018), a performance piece commissioned for the 2018 Biennale of Sydney (BoS) (16 March–11 June 2018), Tabet offers a discursive journey that moves beyond the work's site of the Sydney Opera House to reflect on architectural projects and untold stories that link Lebanon to Australia through the lens of global modernist architecture. Dear Mr Utzon centres on the life of Danish architect Jørn Utzon, the architect who designed the Sydney Opera House, from which Tabet weaves a personal story to reveal the contradictory histories of the building's past. Drawing heavily on devices found in fiction, Tabet's return to storytelling, reminiscent of his work Dear Victoria (2016–ongoing), centralises the stories of people who are closely or tangentially involved in the Opera House's history, in order to open up audiences to new imaginative possibilities that re-consider the building.

RSFI want to start by discussing your most recent work, Dear Mr Utzon, commissioned for the 2018 Biennale of Sydney (BoS). Your intervention focuses on the life of Jørn Utzon—the Danish architect who designed the Sydney Opera House, where your intervention is staged—and excavates the story of an unrealised architectural project he designed for the Jeita Grotto in Lebanon. How was the plan for this work for the BoS realised? And can you address how and why it is important for you to link these two disparate locations of Australia and Lebanon, apart from your own personal connection to Lebanon?

RTWhen I was invited to participate in BoS, it was under the premise that I could fill a space with large sculptural installations. However, I knew it would be difficult to spend sufficient time in Sydney and present a project in a country I have never been to, in a context I knew little about. Similarly, transporting an existing work to Sydney did not make much sense. Initially, I did not think I could participate, but, as these things always go, a large component of my work relies on accidents and side conversations. It was only when BoS Artistic Director Mami Kataoka mentioned that the Sydney Opera House was a biennale site—one she was interested in reclaiming—that the project began to take shape.

From an architectural perspective, I did not have much of a connection with the venue, apart from as an iconic, recognisable structure. However, when I came across an online article that mentioned Jørn Utzon had submitted a proposal to build a subterranean theatre in Jeita Grotto, Lebanon—a minor reference to an unrealised project—this offered me an entry point to look further into the history of Utzon and his architectural practice. From there I spent a day going down the rabbit hole, delving into Utzon's plans for the theatre.

Through my research I learned that Utzon was forced to withdraw from the Sydney Opera House project in 1966 after a protracted battle with the then liberal NSW State government over the cost of the project, which culminated in the government suspending payment to Utzon. Two years following his withdrawal, the first project he designed was the Jeita Grotto underground theatre. What is particularly interesting about this design is that Jeita is a cave and so it's impossible to bring a lot of construction material on to the site. Utzon's way around this was to orchestrate a procession of people carrying modular construction elements which would be built through a performative act—one where people would congregate and tell stories around a lit fire in the cave. The union of architectural construction, performance and storytelling fits perfectly with my own practice.

In this sense, Dear Mr Utzon is another facet for understanding how I work, which is often not only about the production of objects but about gathering the orchestration and details of a particular narrative which has the ability, hopefully, to transform an object that is already there. The research process opened up new ways of thinking about how I could make the iconic Sydney Opera House more human through the act of storytelling. Often buildings of the stature of the Opera House are less approachable and more distant to the public for reasons to do with conservation, stature and national identity. As such, my intervention seeks to re-humanise the building by making it more brittle, more complex, and by highlighting its contradictory position within the context of Sydney.

RSFAs you've noted, the construction of the Sydney Opera House is shrouded in a complex and controversial history (most notable for the creative and technical disputes that led to Utzon's resignation), one that is political in and of itself. How did you tackle this complex narrative through your intervention?

RTThe Opera House is one of the most fragile objects I have ever encountered, yet it puts on a together face: a contradiction that became attractive for me to tackle. At the heart of this project, then, is finding a way to disrupt the composed façade of the building. My intention is not to point a finger at its complex history, nor to accuse those who challenged Utzon, but to create an ambiguity through the act of storytelling, so that audiences are not even sure how they arrived at this history. In considering the process, I have relied on some devices to contain the complexity of the narrative.

There were two facts that interested me about the story. The first is that Utzon never saw the completed Opera House in person—after a reconciliation of sorts in 1999, when he was engaged to produce a set of design principles for all future changes to the building, he was by then too old to travel back to Australia—and so it is interesting to me that such an iconic building was never actually seen by the person who designed it. The project near ruined Utzon's career, but at the same time what he produced had so much potential. The second fact is that Utzon was (and still is) the only other architect apart from Oscar Niemeyer to have a building he designed become a World Heritage Site while still alive. This led me to ask: how do you make something that becomes a national and globally iconic success, at the centre of which is a great failure? Of interest to me in all the work I produce is to find a story that contains both of these conditions—the great potential, as well as the failure within that potential. In the act of writing, I'm walking a tight rope between two moments: potentiality and failure.

RSFDear Mr Utzon takes the form of you writing a letter to Utzon on the eve of his 100th birthday anniversary in April 2018. Does the confessional letter format allow for a more personal and tacit history to be articulated? One that moves beyond fact-based events by freeing you up to weave a collective historical narrative across borders and fixed temporalities?

RTDear Mr Utzon is a heavily written story that seeks to link events and happenings beyond simply Lebanon and Australia, offering a way to narrate an overlapping and complex history that repositions how we view the building we are in. The form of the letter gives me a structure where I can locate myself within this history—one that is not only about my personal connection to Lebanon (by way of Jeita), but about how I, or the audience, can locate him/herself within a space and setting as iconic as the Sydney Opera House. From the outset, the viewer assumes s/he is being taken on a narrative journey that is friendly and familiar, so the letter format is a narrative device that allows for digression and can lead us to reflect on darker histories contained within the building's history. For example, one story involves the kidnap, holding for ransom and subsequent murder of an eight-year-old boy in 1960, whose parents had won a substantial amount of money in a lottery held to raise money for the building of the Opera House, which again, implicates the building in multiple histories, personal and political.

What I propose through my practice is that in order to find yourself within major historical moments one needs to find a breach or a crack within the history in which to position oneself. For me the 'crack' is the dismissal of Utzon and his consequent plans for Jeita. In this sense, Jeita is the excuse, not the end product. This is not a nationalist project to insert Lebanon into Sydney, but rather it allows me to locate my voice more strongly in Sydney. Similarly, by staging my performance in the Utzon room, which will be turned into a domestic interior, it becomes a sort of entrapment for the audience by providing a safe familiar space that then guides us through an unexpected history of the building and its controversies. Many of the narratives I present seem stranger than fiction, and there has been a recent trend, or device, where artists locate themselves or a fictional character within a different history. What is apparent through my work is that you don't need to fictionalise reality. By simply excavating the history of the object or architectural structure, these links become apparent.

RSFIn terms of locating your intervention in the context of Sydney, a city that has a large Lebanese community, but a city that has also attracted media attention for the Australian Government's hostile and racist attitude towards those it calls 'illegal arrivals', what, if any, are the deeper socio-political or cultural concerns guiding this intervention?

RTWhat is interesting is how complex socio-political histories are occurring in one of the most famous and photographed buildings in the world. By highlighting the contradiction at the heart of the story, it allows us to think through our contemporary condition. Australia has an extremely complex and problematic relationship with the refugee crisis; at the same time, I'm not concerned with explicitly using this project to speak directly to the refugee crisis, but by way of Utzon's narrative this will somehow be addressed or reflected upon. For example, the ease with which Utzon was let go, partly because he was not a native Australian (with the public perception at the time being that an Australian could do a better job), places questions of nationalism at the core of the Sydney Opera House. Similarly, Jeita Grotto was used by right-wing Christian militias to store ammunition during the Lebanese Civil War (1975–90), something the journalist Robert Fisk has written about, and so, in this sense, the narrative of Mr Utzon hops between these two geographic locals even on a political level. I don't think it's accusatory; I'm simply opening the box.

RSFJeita Grotto, like the Sydney Opera House, is a national symbol and important cultural venue, having long been a site for artistic interventions, with notable musicians Karlheinz Stockhausen and François Bayle both staging performances in the space in 1969. The site was partially closed due to the civil war—a historical rupture that had detrimental bearing on the country's de-development and later re-development. I wanted to ask how your intervention reckons with these historical ruptures?

RTWhat is noteworthy about Jeita, or even Baalbek, is that they are both sites of national pride, artistic intervention and conflicting histories. I am interested in how iconic places, usually of an archaeological or geological nature, have been appropriated by politicians for various end goals. That being said, these sites have always been able to transcend the political agenda ascribed to them because they are bound to a timeline that operates on a million-year scale. Moreover, these archaeological sites are an accumulation of those moments that reverberate against each other. It's not about atonement or reconciliation for me, but rather about underpinning the contradictory conditions and transcending timely concerns in order to accumulate more or complicate our understanding of place and history. I am not interested in resolution or consensus because that creates a state of balance. For me, in terms of philosophical or artistic considerations, a state of balance is completely complicit in creating a condition of status quo.

RSFThere are other examples of modernist architectural projects from this period in Lebanon, such as Oscar Niemeyer's abandoned International Fair site in Tripoli, commissioned in 1963 and almost finished by 1975 when civil war broke out, again pointing to the overlapping progress and rupture in the country's architectural construction. This trend towards international-led modernist architecture projects that occurred before the war in Lebanon seems relevant to your project. As such, how do you position Dear Mr Utzon within the broader context of modernist architecture in the region?

RTIt's interesting that you say this. While I was doing research in the offices of Harry Seidler in Sydney—an Austrian-born Australian architect who is regarded as a leading figure in the modernist architecture of Australia and was good friends with Utzon—I came across a box of letters from leading modernist architects demanding that Utzon be reinstated as lead architect. It was a campaign spearheaded by Seidler, which led to Louis Khan, Marcel Breuer, Kenzo Tange, and others voicing their support not just for Utzon but also for the practice of architecture itself. One of the letters of support had been sent from Beirut by the Swiss architect Alfred Roth who, in collaboration with Alvar Alto, designed the Sabbagh Centre in Hamra, which made me think about the promise of modernism across the globe—not just in Lebanon or Australia—that was centred on the idea of a common architecture and design language that could transcend national concerns through a unified style. It also led me to think of the ways in which Lebanon and Australia were trying to invent or create an identity. At the time, Australia was looking to shape its identity in opposition to its inherited penal colony history; similarly, Lebanon was then a fairly recent republic preceded by 500 years of Ottoman rule and, more recently, the French Mandate period (1922–46). Thinking of modernism within this context could be read as a reaction to the inherited national identity of these two countries.

It's also interesting to note that it is not only international architects who come and work in Lebanon during this period in the 1950s and 1970s, but you also have local architects that are using that language of modernism, such as Joseph Philippe Karam or Antoine Tabet—and Pierre Khoury, who built most of the country. So, it's not about importing voices, but about asking how the modernist trend can offer a shared vernacular and unified voice. Moreover, this was a period where the practice, principles and ethics of architecture were different to those found today. For example, Le Corbusier, who at the time was the most important architect in the world, accepted a commission from Utzon—a lesser-known architect who was then only 39 years old—to make a tapestry for the Opera House. Today this would seem impossible, and I do not say that out of judgement or nostalgia, but because these are reflections of the time.

RSFI am interested in how your body of work addresses architecture's role in creating social exclusions. Here, I am specifically speaking about the sculptural installation Colosse Aux Pieds D'Argile (2015), which I saw at the Istanbul Biennial. What I found interesting about the work was how your use of material—found marble columns from a 19th-century villa and concrete cylinders used in the construction of a skyscraper that sit atop of the ruins—are directly involved in the exclusionary politics of 'place-making'. How does your practice as an artist, given your training as an architect, contribute to the discourses on broader socio-political and ethical concerns of urban reconstruction?

RTWhen I was studying architecture in Beirut, there was a lot of conversation around preservation and how to think through the past in relation to the present. I felt caught between two clans: the 'developer clan', who were keen to create a different kind of architectural language that could sustain the cities growth; and the 'restoration clan', who follow a preservationist approach to keep things as they are. I was never convinced by either of these positions, as I felt they were both guilty of producing hegemonic discourses. So when I came across the marble columns from the villa and the contemporary concrete materials that make up the sculptural installation Colosse Aux Pieds D'Argile (2015), it was interesting to find two different construction materials across a 100-year history on the same site. What is interesting is that at the time of its construction, the villa was a borrowed style that reflected an economic class that was a rupture to the city's surrounds—not too dissimilar to skyscrapers today. Yet, with our distance from the event, the villa now comes across as a humble traditional building (despite it being built by individuals who were funding the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), which resulted in famine in Lebanon). The temporal distance I sought to highlight in this work allows for a different material confrontation in which the marble columns foreshadow the concrete blocks, in turn positioning the skyscraper development in a different light. I think artistic production allows me to move between these multiple temporalities, which, through the present act of viewing, bring these materials together rather than positioning them as two opposing histories.—[O]

—