Redressing Gender Imbalances at National Gallery of Australia

Left to right: Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now co-curator Elspeth Pitt; Jessi England, Know My Name programme and campaign manager, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Courtesy National Gallery of Australia.

Left to right: Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now co-curator Elspeth Pitt; Jessi England, Know My Name programme and campaign manager, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Courtesy National Gallery of Australia.

The Know My Name initiative at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) wants to reframe the story of Australian art by adding to this history the voices of brilliant and creative women, too long unrecognised, and who continue to be under-represented across public and private collections.

Know My Name began with an exhibition pitch by NGA curators Elspeth Pitt and Deborah Hart of a survey of painting, sculpture, and art from all women artists since 1900. When Ocula Magazine first spoke to the gallery, the Covid-19 crisis was just unfolding. When the gallery closed, Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now transformed into a two-part show extending over a year into 2021, with part one taking place from 14 November 2020 to 4 July 2021, and part two scheduled to open in July 2021.

More broadly, the exhibition pitch sparked a movement across the gallery that resulted in a refocus on gender equality, led by NGA Director Nick Mitzevich. NGA programming became centred around this initiative, with an extensive (now virtual) conference with theorists and authors like Griselda Pollock and Jennifer Higgie taking place between 10 and 13 November 2020, a takeover in collaboration with oOh!media of over 3,000 print and digital billboards across the country with images of works by women artists, and a Wikipedia edit-a-thon, which saw 80,000 additional words added on Australian women artists.

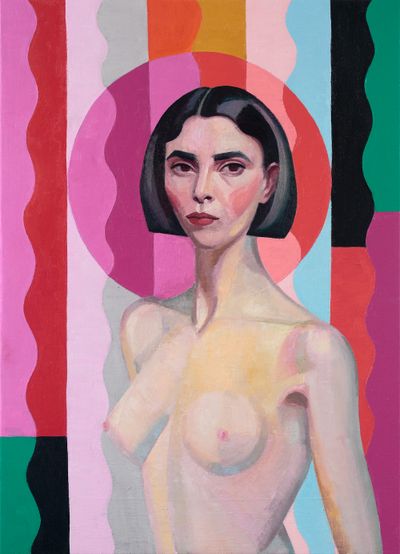

Additional exhibitions were also planned, including other Know My Name affiliated exhibitions such as In Muva we trust, a takeover of the gallery's façade by Warrang/Sydney-based collective, Club Ate (Bhenji Ra and Justin Shoulder) (28 February–9 March 2020), and The Body Electric (22 June 2020–January 2021), exploring sex, pleasure, and desire in the work of artists like Sophie Calle, Pixy Liao, Tracey Moffatt, and Cindy Sherman.

In this conversation, co-curator of the exhibition, Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now, Elspeth Pitt, and Know My Name programme and campaign manager, Jessi England, reflect on the critical reasons why art history has neglected women artists or failed to recognise their contributions, and the scarcity of information on the public record.

As Pitt and England note in this interview, intriguing threads have been revealed in the research undertaken by NGA, from hidden histories to previously unknown connections. The expansive Know My Name publication, with short essays and artist profiles, long-form essays, interviews, and a bibliography of over 113 authors on 150 women artists, will highlight some of these and anchor them in contemporary art discourse.

The gallery is also collaborating with The Countess Report, an online resource on gender equality in the visual arts in Australia, and initial data has revealed significant inequality in the gallery's collection, with Australian women representing 25.48 percent of the Australian art collection, men representing 72.97 percent, and no data on non-binary artists recorded. Know My Name sets out to change that historical gender bias within the collection, exhibitions, and public programming.

Recent global events that have woken the world to the equally concerning racism epidemic aligned with the gallery's focus on women artists of colour, amplifying the cultural stance of the gallery as an ally. As noted in this conversation, the position of the arts during these times is now being re-examined and questioned.

EKWHow did the Know My Name initiative at NGA begin? What was the initial turning point for the gallery?

EPIn late February last year, our director Nick Mitzevich was trialling a new exhibition pitch system whereby the curators would come together to pitch ideas over five minutes with a maximum of ten images.

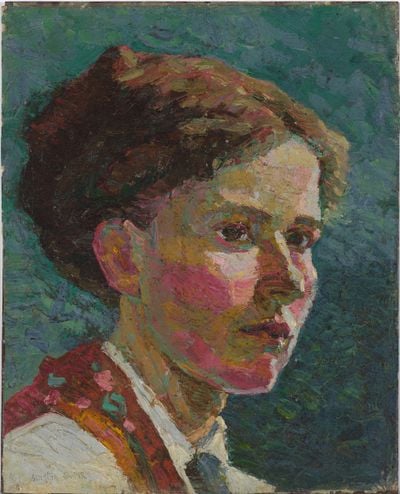

Deborah Hart, the head curator of Australian art at NGA, and I proposed an exhibition of Australian women's work—an intensive survey of 100 years of painting, sculpture, and art across the board. It was a slightly nerve-wracking process, but everyone was excited by the idea.

The introductory slide comprised a series of women's portraits and self-portraits. They looked so compelling, staring out at us all, and we stated that our aim was to make those women household names in the same way that artists including Brett Whiteley, Sidney Nolan, and Arthur Boyd, are.

The broader Know My Name initiative grew and progressed quickly from there—the exhibition certainly aligned with the director's broader ideas and vision for the gallery.

JEThe idea for the exhibition led to a broader conversation about how the gallery could engage more with global gender equity movements in the arts. It seeded and inspired a whole lot of thinking and very rapidly expanded from Elspeth and Deborah's idea for an exhibition, into a comprehensive initiative that could take in programming, partnerships, and connecting with the public.

It also really tied in with Nick's vision for the gallery; for the NGA to take a new position in terms of cultural leadership. As the nation's collecting institution, we need to be taking a more active role not only in terms of what we do as an organisation, but how we can take a position that encourages others—using our national voice to connect with broad audiences.

From a curatorial perspective, we need to look at the future and the past concurrently.

The NGA also connected with The Countess Report early in the process. The gallery had started to look seriously at its collection and recognised that only about 25 percent of the Australian art collection was by women artists. That was a real wakeup call and exposed an opportunity to not only own the reality of that situation, but also use it as a real instigator to bring about organisational change and do it in the public eye.

We aren't hiding these numbers; we acknowledge that this is where we are, and we are going to work across the board to shift this quite significantly. We're going to do it in a celebratory way, that also embeds organisational change in the process.

EKWCould you talk me through some of those methods that the gallery has implemented these efforts?

JEOne of the significant things that has come out of Know My Name is the implementation of new gender equity guiding principles across the organisation. This is a vision across programming, collection development, and our organisational structure that ensures we will be embedding gender equity moving forward.

In May, we established a working group of internal and external stakeholders to consult and collaborate on the development and implementation of a Gender Equity Action Plan, putting key actions into place across every aspect of the organisation to bring about change and ensure the commitment remains long-standing.

In terms of the collection, given the size and level of imbalance, parity is going to take some time, but by making that formal commitment, we're ensuring that shift happens. Enabling this through programming, exhibitions, public programmes, and how we partner, will bring this work into everything we do, not only gender equity but diversity more broadly.

We hope that one of the impacts of the exhibition and broader initiative will be to encourage artists, their families, collectors and colleagues to work with us to bring to light lesser-known and neglected works of art.

Even with the work done by The Countess Report, when they started to look at the process of the collection and the rationale of who created the work and their gender, it was noted, for instance, that gender wasn't always recorded—it was a very binary approach. But this research has brought about a whole lot of change moving forward in how we can think about embedding gender equity and diversity into collecting and recording data.

EKWHas there now been a conscious push to collect more artwork from women by the gallery?

EPYes, definitely. The gallery is committed to gender parity in its future acquisitions and programmes. But this has its challenges. From a curatorial perspective, we need to look at the future and the past concurrently. Certainly, that's been a focus of the exhibition, since, temporally speaking, it begins at 1900.

If we look at the NGA collection, there are no sculptures by women artists before 1920. To remedy this omission and imbalance requires intensive historical, archival, and private collection research. This kind of work doesn't occur quickly—it requires us to play the long game.

There's fascinating work in this vein to follow, but it won't necessarily come easily. We hope that one of the impacts of the exhibition and broader initiative will be to encourage artists, their families, collectors and colleagues to work with us to bring to light lesser-known and neglected works of art.

EKWI was thinking about some of the specific artworks that you may have found during this process. Could you tell me about a couple of artists that you may have unearthed from this research?

EPTo date, many of the acquisitions we've made have revolved around work of the 1970s and 80s. There was so much pioneering work being made in that second-wave feminist era, and one of the alarming things for me, both personally and as a curator, is that so much of that work—which is ephemeral, collaborative, performative—has not been collected deeply or holistically.

This is a significant failing, I think, on the part of many state and national art collecting institutions, although it is not necessarily surprising, given that most collections are object-based.

Among the acquisitions that I'm most passionate about is a group of works by Frances (Budden) Phoenix, an Adelaide-based artist who worked with embroidery and doily-making and subverted its ostensible 'prettiness' by embedding strident political messages within it.

The acquisition evolved over the course of a year, with assistance and introductions made to the artist's family by colleagues including Louise R. Mayhew and Julie Ewington, and travel and interviews undertaken with the artist's family before a group of works was assembled and acquired.

We've also made acquisitions by Mazie Karen Turner, who was the partner of the artist and poet Richard Kelly Tipping. Turner began making beautiful, sprawling, yet intricately detailed blueprints on the roof of her Bondi flat in the early 1980s after she had had her first child.

We endeavoured to identify moments in which women led progressive practice, or formed new types of art and cultural commentary, and the works included are diverse.

Turner spoke about 'scatter', and of having to become accustomed to the 'scatter of things' after having a child, and she began employing scatter as an aesthetic and as an art-making strategy. Assembling toys and domestic paraphernalia on long strips of photo-sensitised fabric, she would then expose the prints to the sun, recasting their patterns in vivid blue.

These are just two of a greater swathe of acquisitions that we've made and will continue to make.

EKWHave you found any interesting parts of Australian art history in particular that you'll include in the exhibition?

EPThe exhibition has a temporal spine or span, but it plays out according to a range of thematics. We endeavoured to identify moments in which women led progressive practice, or formed new types of art and cultural commentary, and the works included are diverse. Some are well-known, others are less so.

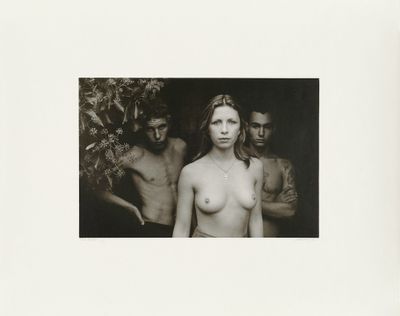

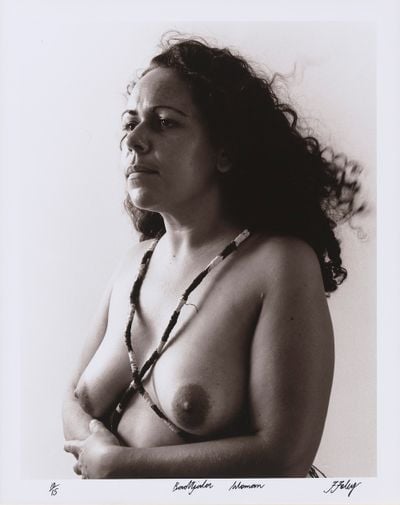

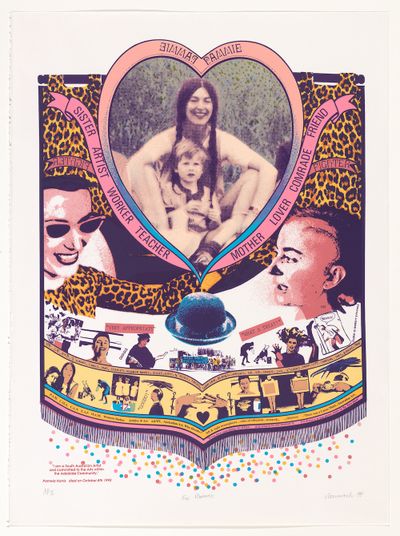

Among my favourite works are photographs originally published in A Book About Australian Women (1974), which featured Australian women artists, activists, mothers, and sex workers taken by Carol Jerrems with interviews by Virginia Fraser.

The intimacy of Jerrems' work is echoed in Fraser's interviews, in which the women reflect on themes including work, marriage, mothering, abortion, and feminism. At a time when women's experiences were not typically the subjects of art and literature, A Book About Australian Women was a significant gesture.

For me, it was one of the works that had to be in the exhibition. Although it, or parts of it, have been exhibited before, we also felt that it needed to be shown to a new generation.

EKWHave there been narratives that you've seen from the beginning of the exhibition to the end? Or reoccurring themes that you've noticed from the early artists to the artists who are practicing now?

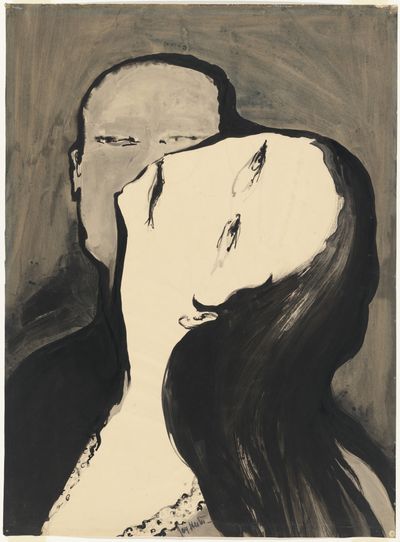

EPWe were just talking about this today. Again and again, so many of the artists included in the exhibition had to give up or postpone their careers in order to support those of their husbands, who were often artists themselves.

Within the scope of this project, we also wanted to 'play' with histories, and to form connections that one may not necessarily expect.

In a way, this is not something we necessarily wanted to draw attention to, as the exhibition aspires to demonstrate the achievements of women artists, but it is a theme that recurs, and one that weighs heavily. Equally, however, many of these artists came to achieve career success or formed ambitious bodies of work later in life, once children had been raised and, sometimes, after husbands had been departed from.

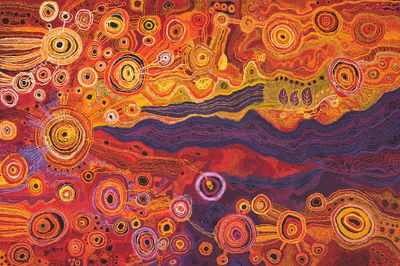

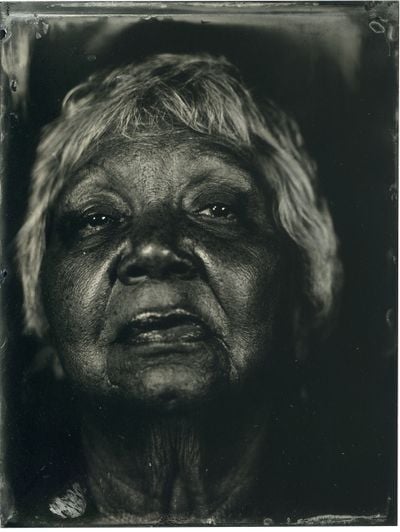

Certainly, the quantity and calibre of work by artists into their seventies and eighties is remarkable. Here I am thinking particularly of artists like Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori and Rosalie Gascoigne.

JEI know as well, Elspeth, that something that you and co-curator Deborah Hart have been very aware of throughout the show, is this idea of lineages across time.

EPDefinitely. That was something that we were interested in from the outset—in lineages or genealogies—because you can't forge a history without first sensing or apprehending the links between artists; be they real, suggested, aesthetic or creative.

We have to note that this is certainly not the first undertaking of its kind, and there have been a good many exhibitions that have focused on the work of women that have set forward histories and relationships between women artists through time. Among the first was Janine Burke's Australian Women Artists: 1840–1940 at the Ewing and George Paton Gallery in 1974.

But while these histories have been written, often, due to economic circumstance or lack of financial support, they have not always been reflected in substantial publications. So, although these histories exist, they're not always that well known, which seems remarkable, because you would think that by now, they would be.

Within the scope of this project, we also wanted to 'play' with histories, and to form connections that one may not necessarily expect. For example, we wanted to make selected aesthetic connections between artists through time, drawing together artists such as contemporary painter Gemma Smith, and Clarice Beckett, who had worked early in the 20th century. Both artists are exquisite and sensitive colourists, and it was fascinating to witness the resonance between their work.

There are other pockets of research that truly challenge the dominant histories. Take artists such as Margaret Worth and Dora Chapman. Both women had been overshadowed by their artist partners Sydney Ball and James Cant, respectively. While people tend to think that Worth took visual cues from Sydney, she learned the first principles of abstraction from Chapman, who had taught her at the South Australian School of Art.

These kinds of connections actually help us to reconsider the ways in which abstraction developed in Australian contexts.

EKWCould you talk a little bit about the intersections of different events and collaborations with the exhibition, as well as the publication?

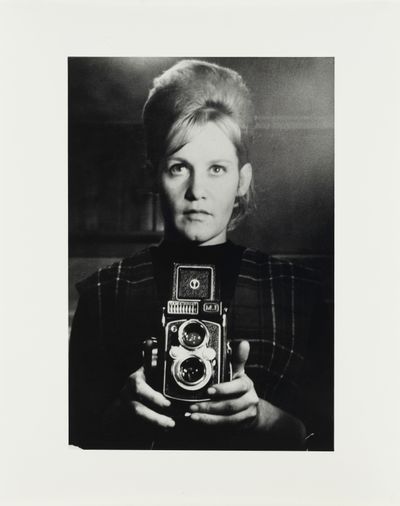

EPYes! There are many events and collaborations. One of these has been with Micky Allan, a feminist artist who emerged in the 1970s. Micky's first solo show in 1978, Photography, Drawing, Poetry: A Live-in Show, brought the domestic space to bear on the gallery.

Visitors could look at her work, they could read her poetry, make a cup of tea, watch TV, lie in her bed, relax, and experience art in a totally different way—as part of the rhythm of everyday life.

We've been working with Micky, not to restage, but to capture the essence of what she was trying to do at that time—to break down the seeming impenetrability of art and galleries.

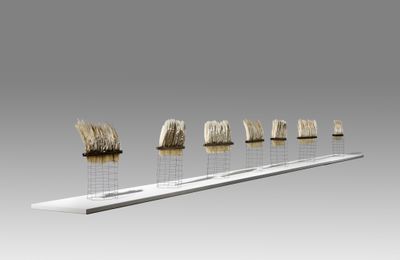

Along similar lines, we have also been working with contemporary choreographer and dancer, Jo Lloyd. We came to Jo with an idea, asking her to extend the prior practice of the performance artist Philippa Cullen, who began working in the early 70s but died very young at the age of only 25.

Philippa Cullen was a pioneering performance artist, but she is now little known within an art historical context. Cullen's principal interest was for the movement of the body to generate sound, and she achieved this by working with early electronica and theremin.

Jo conducted intensive and intuitive research within the Cullen archive and has developed a work that she considers to be a collaboration with Philippa. There are some beautiful synchronicities between Philippa, Jo, and their respective practices—even down to the fact that in the year Philippa died, Jo was born.

The work is an incredibly personal and considered response from Jo's perspective. We've been so fortunate to have the support of Phillip Keir and Sarah Benjamin, without whom this work would not have been able to come to fruition.

JEIn terms of other events, there's an extended series of collaborations and partnerships that have come out of Know My Name, and that are continuing to progress.

I've mentioned The Countess Report, and our work with them will be continuing. They've been involved in some of the public programming that will be happening in conjunction with the exhibition and have also accepted our invitation for them to join the Gender Equity Action Plan working group as independent external contributors.

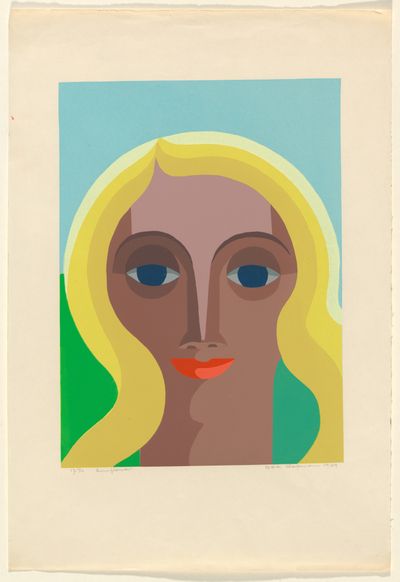

The partnership with oOh!media, one of the largest out-of-home advertising agencies in the country, has been a really significant collaboration—they partnered with us fairly early into the initiative. They own a vast array of print and digital billboards and assets in outdoor public spaces, train stations, bus shelters, in retail buildings and office blocks—thousands of people pass these sites every day, many who've never been into a gallery.

They were very keen to look at how they could support Know My Name and its intentions to celebrate and raise awareness of the contributions of women artists and utilise their spaces to support the project. As part of that partnership, we launched a national outdoor art event where 76 works from the gallery's collection by 45 women artists have been placed on digital and print assets across the country.

Phase one of the project was rolled out over six weeks from the end of February 2020. Phase one was about 3,000 assets. Phase two is launching in November and will run through to January. Although phase two will be slightly smaller in scale, it will also include a partnership with Google Australia using Google Lens technology.

The idea has been to take the collection and take the work of artists to a very broad public. It's aligned with the idea that came out of the #5WomenArtists campaign, which has had a wide influence, but also with Know My Name.

It's this idea of raising awareness and the profiles of Australian women artists to a broad public, reaching out to people who may not visit a gallery—people who are in their cars, driving down the highway, or in cities, in a shopping centre, and unexpectedly see these works of art; see these artists' names. It's an opportunity to use these amazing assets in a way that shines a light on the work of women artists, and it's been so wonderful approaching the artists.

So much of this project has been about inflecting the existing history with women's living memory, and what has previously been anecdotal in many cases, is now recorded in words that have substance and strength.

Many of the artists featured are living artists and hearing their responses from when we first came to them with the idea has been amazing. Artists like Margaret Worth, who said this was always how she envisioned her work, but never had the opportunity to have it at this scale.

As part of that partnership with oOh!media and AMP, who own the Macquarie Centre in Sydney, we had a two-hour-long Know My Name takeover of an extended selection of billboards within that shopping precinct.

EKWWhen it comes to gender equality across all the arts, are you noticing a shift in other galleries now and how they're doing things?

JEWe're very aware this is a global movement; the industry has become very aware of this need, and institutions across the board are working in their own ways to bring about change to focus on the work of women artists.

We have found with Know My Name that people are wanting to align with it and recognise its importance. This has included artists, arts communities, and grassroots organisations.

Prior to taking on this role, I was living in Newcastle, in regional Australia, and I remember the ripple through the art community when the launch of Know My Name first happened. After taking on this role, I felt a sense of how desperately this is needed.

Right now, given the crisis that faces everybody, the art community is really one of the industries that is under threat; women artists are so vulnerable in this space. So we'll be looking at how we can continue to support, and also continue to educate and inspire the public about how important the role the arts can have in these times, for everybody.

EPIt's been such a collaborative exercise. We're working with public and private collections, collectives, and artists from Australia and internationally. We are delighted and so grateful to our colleagues. Galleries across Australia have been so generous with loans of work, in facilitating and furthering research.

The related publication is a substantial undertaking that encompasses the work of some 113 authors writing on more than 150 artists. There are 150 short essays and artist profiles in addition to longer-form essays, interviews, and a bibliography. It's going to be a magnificent addition to the literature. We've been calling it a community-building exercise. Without wanting to sound saccharine, that's really what it has been.

There is so much interesting material coming to the fore. So much of this project has been about inflecting the existing history with women's living memory, and what has previously been anecdotal in many cases, is now recorded in words that have substance and strength.

JEOn that note, one of the other significant partnerships that we've had is with Wikimedia Australia. Over the weekend of International Women's Day, in partnership with Wikimedia, we ran a series of national Know My Name Wikipedia edit-a-thons at seven national locations, including one here at the gallery in our specialist research library.

That was amazing for a number of reasons. Only 18 percent of Wikipedia entries were about women, and in the arts, it's far less than that. We used this as an opportunity to have a focus on increasing information available about Australian women artists.

Over the course of the weekend, we had about 120 volunteers—many of them who were coming to Wikipedia editing for the first time—run by an incredible group of volunteer Wikipedia facilitators. We created 63 new pages about Australian women artists, and over 100 existing articles were edited. Close to 80,000 additional words were added to Wikipedia about Australian women artists. These are the kind of things that actually really change what information is available.

One of the things that struck me, because that was the first time I had encountered a Wikipedia edit-a-thon, is that everything has to be cited—there's a stringent process of editing anything that doesn't have a notable reference against it.

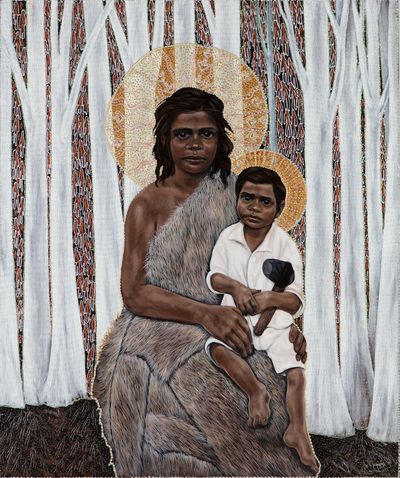

We also found that First Nations artists, or artists from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, often they are the groups of artists whose work hasn't appeared or been written about to the same extent.

There's this catch-22 of needing the information that has been published, people need to be researching and publishing it, and then once the material has been published, it enables broader distribution. It was quite profound in terms of how important it is for curators, researchers, and academics to be doing this work. It's all part of the bigger picture.

The other thing is the conference that we are planning in conjunction with the Know My Name exhibition, which includes a very exciting national and international coming together of artists, curators, and academics to talk through the past, present, and future possibilities.

This is a partnership with Australian National University, Canberra; the University of New South Wales, Sydney; the University of Melbourne, and the Australian Council for the Arts. We are working across the board with these partner organisations, who have a huge amount of enthusiasm and passion for this work. Know My Name provides a really great opportunity to channel this energy into enduring outcomes.

EKWYou mentioned the wider effect of this on First Nations women artists. Did the gallery have a response to the global Black Lives Matter movement, and was this something that came into the new programme?

JEBlack Lives Matter is an important cultural movement, but it didn't directly influence our programme. First Nations voices were always a priority for the Know My Name exhibition and conference.

As the custodian of the largest collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art in the world, the National Gallery of Australia is committed to sharing the stories of First Nations people. Conference keynote speaker Genevieve Grieves, a Worimi woman, will examine the role of colonialism in the gendering of Australian art and collections.

Dr Crystal McKinnon, a Yamatji woman, will lead a discussion on decolonising feminism for the NGA's Annual Lecture on 12 November. Dr McKinnon's presentation will be followed by a discussion on art, gender, power, and feminism with Kimberley Moulton, a Yorta Yorta curator, writer, and curator, and Wemba-Wemba and Gunditjmara visual artist, curator, community arts worker, writer, and academic Paola Balla.

The gallery is also embarking on a Reconciliation Action Plan and has established a working group to develop and implement change across the institution.

So gender equity and reconciliation will continue to be priorities for the institution. When Know My Name as a project eventually wraps up, those ideas will not be lost, because everyone here is so enthusiastic and so dedicated to what that means. It's really about an institutional shift and opportunity into the future.—[O]