Reiko Tomii

Reiko Tomii. Courtesy Reiko Tomii.

Reiko Tomii. Courtesy Reiko Tomii.

In 1969, Horikawa Michio, schoolteacher and member of the artist collective GUN (Group Ultra Niigata), filled out the customs paperwork to mail a one-kilogram river stone from Niigata, the proverbial 'backside of Japan', to President Nixon. In return, Horikawa received a thank you note for this 'most unusual Christmas gift'—a muted anti-war protest (an act of 'throwing stones'). This stone and its paper trail are just one of the many delights on view in Japan Society's Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s (8 March–9 June 2019), curated by curator and art historian Reiko Tomii. Over the last three decades, Tomii has worked assiduously to unravel the dizzying array of moments, movements, and counterpoints that make up Japanese art practices of the long 1960s. Thanks to her, messages like Horikawa's are no longer mere objects of curiosity, as they were to Nixon's White House, but critical tools for the writing of a global art history.

Growing out of Tomii's award-winning 2016 book of the same title, Radicalism in the Wilderne__ss centres on the work of artist Matsuzawa Yutaka, and artist collectives GUN, and The Play, with this tightly curated and archivally rich exhibition demonstrating how each developed practices that moved past the object, and into the—at times mental, at times physical—landscape. In the space of a few rooms, Tomii presents both connections (points of contact between artists, in exhibitions, publications, and correspondence) and resonances (the independent development of strikingly similar methods, terms, and artworks in contexts).

Based in Shimosuwa, a mountain town in central Japan and his ancestral home, Matsuzawa Yutaka developed a unique text-based practice that instructs viewers to visualise phenomena such as the artist's death, distant exhibitions, and—most commonly—the vanishing of civilisation. Informed by his study of parapsychology, esoteric Buddhism, and avantgarde modernism, Matsuzawa's work revises the traditional canon of conceptual art. In particular, his invocation of the Buddhist term kannen (meditative visualisation) in his 1960s practice parallels the invention of Western conceptual art, which would later be translated into Japanese with the more secular and scientific gainen, which is a newly made Japanese word for philosophy in the 19th century. Ironically, the politics of translation here foreclose alternative understandings of dematerialised practices that themselves relied heavily on language.

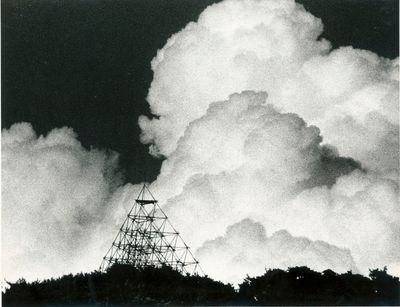

GUN, which was co-founded by the stone-collecting Horikawa Michio together with Maeyama Tadashi, is well known for their performance and environmental works, such as Event to Change the Image of Snow (1970), in which they dyed a field of Niigata's thick and fast-falling snow in red, blue, and green pigments. In a similarly whimsical vein, The Play, a collective of Kansai-based artists with a changing membership, dedicated themselves to a series of 'happenings' that took advantage of the nearby mountains, rivers, and fields, with the intention to create time, which they spent together. For Thunder, for ten summers starting in 1977, the collective built a pyramid topped by a lightning rod atop a mountain to collect lightning that never struck. Tomii notes that, in comparison to American artists, the modus operandi here was to work together 'in nature nearby'—as opposed to working solo in nature far away. It is this dedicated and accessible collectivism that still feels radical today.

Entering into conversation with Tomii is a reminder that art history, like the spaces these artists gravitated toward, is an 'open field'. In this discussion, she elaborates on Radicalism in the Wilderness, and the research and experiences that fed into it.

DBThe field of Japanese art in the expanded 1960s has itself expanded in the last decades. Can you tell us about the exhibition history of postwar Japanese art in the English-speaking world, and where you have chosen to focus your scholarship?

RTThe exhibition history of postwar Japanese art began in 1994 with Alexandra Munroe's Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky at the Guggenheim Museum, and it's been 25 years since then. Although we had no flood of exhibitions in this field akin to the number of exhibitions of Chinese contemporary art over the same period of time, what was shown is critically focused and extensive enough to survey a long stretch of the expanded 1960s. You can think of Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art: Experimentations in the Public Sphere in Postwar Japan 1950–1970 at the Getty Research Institute in 2007; Gutai: Splendid Playground at the Guggenheim Museum in 2013; Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha at Blum & Poe in 2012; Little Boy: The Arts of Japan's Exploding Subculture at Japan Society in 2005; or Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde at MoMA in 2012, among others. I was involved in them in one capacity or another and helped shape intellectual engagements, if not curatorial directions.

There has been a good deal of resource building in our field in the English-speaking world. And I was riding on this wave. In an ideal scenario, scholarship is not a solo endeavour, but a collective exercise. Many of us in the field of PoNJA—Post-Nineteen-forty-five Japanese Art—embrace Yoko Ono's instruction as our motto: 'A dream you dream alone is only a dream; a dream you dream together is reality.' I believe this motto can be extended to the larger project of narrating a world art history of modernisms, which is a huge undertaking that transcends individual scholarships. At the same time, I had been building my own scholarship, in which I consciously endeavoured to devise historical armatures, comprised of frameworks and concepts—large and small—to narrate postwar Japanese art history. Collectivism, conceptualism, performance art, Anti-Art (Han-geijutsu), Non-Art (Hi-geijutsu), Tricky Art, contemporary art (gendai bijutsu), and so on—they constitute structures of the narrative I was constructing.

DBLike your book, this exhibition focuses on the practices of two artist collectives and one artist. Juxtaposed, they make for fascinating study. How did you select these three? And perhaps more to the point, what are the stakes of deciding to focus on just three practices as opposed to a much more sweeping survey?

RTThis is an easy question to answer. I came to realise two things during the process I mentioned above. First, a survey exhibition is a great visual showcase but not necessarily a great intellectual classroom. In a mega-survey, individual works may revel in a 'wow factor', but often tend to fail in registering an intellectual impact. If we keep showing 'wows' without intellectual amplification, 1960s Japanese artworks will forever remain curios in a global wunderkammer of modernism. Here, 'intellectual' is not a comfortable word, but what I mean concerns the expansion of a knowledge base—to understand why artists create what they create, as they make certain decisions within the specific circumstances they are dealt with in a large history. My attention to history is bottom-up, starting with local examples, listening to local voices of artists and critics, thinking in terms of the local, with one eye however always kept on the global. I do not impose much of a top-down perspective based on an existing Eurocentric framework, concept, or movement, even though that nonetheless serves as a point of reference for ultimate comparison for me. The key to my project is the artist's decision.

I came upon this idea at the time of PoNJA's first conference in 2005. At PoNJA, in order to open our area of study to art historians outside our field, we have made it a rule to invite Western modernists at the host institution or in its environs. At the first conference, held at Yale, we invited David Joselit as a commentator to the panel 'Ephemerality in the 1960s'. He expressed his pleasure at learning about several innovative examples of performance art and installation art from 1960s Japan in his comments. So, after the panel, I asked him in private if he would be incorporating those examples in his teaching, to which he answered 'no', because he explained to me that he didn't understand those Japanese artists' decision-making. This was at once a revelation and a confirmation. A revelation because I realised that even an advanced modernist like him would feel the need to understand the artist's decision-making. A confirmation because that was what I had come to learn to pay attention to as a Japanese-trained graduate student who had come to the U.S. to become a specialist of postwar American art, which I had thought I would be. Lacking a broad understanding of American society and history, I had to learn how American artists of the postwar decades made their decisions informed by their American environments.

The second thing is related to this first point. How do we share the knowledge base with non-specialists? It is not enough to develop a repository of individual pieces of knowledge. They are no more than a set of dispersed points. Points alone do not make strong knowledge. Sometimes, points have to be strung together to make a line, or a narrative tangent. And points and lines thus formed must be hung on a solid framework—that is, say, organised in a perspective or under a concept—to amplify them.

In a way, I am old school. I do very basic art history by looking at an artist and his or her work, and develop an understanding of his or her decisions within a larger context. In doing so, I practice critical biography as a narrative strategy. In a sense, my scholarship has evolved around a critical biography of 1960s art in Japan itself.

DBYour recent book is subtitled International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan. As you've pointed out, we still work in a Eurocentric field. I'm especially curious about the tendency to identify equivalents or analogies from different artistic traditions.

RTI am a bit surprised to hear this from you and others recently, especially those working in area studies. I am surprised because I thought this was a question already settled some while ago. Then again, on second thought, I have to admit that influence is a perennial thorn in the side of the project of multiple modernisms.

It is human nature to try to figure out what's new based on what's known—in most cases, Euro-American examples—and this is where Eurocentrism creeps in. We cannot deny this human nature. A most telling example is Irving Sandler, who looked at the Gutai exhibition at Martha Jackson in 1958. As revealed by Ming Tiampo's archival research for Decentering Modernism (2011), Sandler made mnemonic notations to the Gutai checklist—such as Kanayama Akira looking like Pollock, and so on.

DBWhat are some of the ways that you think we can get away from vexed questions of influence?

RTWhat is vexing is not seeing analogies, parallels, or references with Euro-American examples per se. But if we stop at seeing analogies, we stay trapped in an ingrained Eurocentrism. What we must do is examine the work in question in its own right and explore its narrative tangents—how did an artist arrive at that decision in the locally or individually specific circumstances and in the globally informed contexts? That is what many of us have done as we worked in our own areas, and we will have to continue to do so.

Two things must happen after putting this foundation of local knowledge in place. One is to reexamine the meaning of influence, the other to amplify the contact points. The first question was introduced by Ming Tiampo, based on Harold Bloom's reflections on influence and originality in The Anxiety of Influence (1973), and I followed suit in my book. As I wrote in my exhibition didactic: 'Adopted from literary criticism, "interpoetics" means the enlightened learning of precedents resulting in an innovative response, or responses, to them.'

In the exhibition, GUN's Event to Change the Image of Snow (1970) was partly inspired by their visual knowledge of Dennis Oppenheim's snow-related works, which they saw in the art magazine Bijutsu Techō (Art Notebook), and imaginatively expanded upon in their specific, local situations. Thus, interpoetics differs decisively from facile, unthinking, or outright imitation. We must remember that interpoetics is what Picasso did when he saw African art and what American artists did, learning from and building upon by either following or rejecting Abstract Expressionism. It's a foundation for creativity in any locale.

DBWhat are the implications of this emphasis on contact points for an art historian?

RTThe foundational concept is international contemporaneity, derived from 1960s discourse in Japan, with contemporaneity (dōjisei or dōjidaisei) describing when two things are happening at the same time or era. This definition diverges from contemporaneity associated with 'the contemporary', used in the current global discourse on contemporary art, wherein contemporary, which means 'of this time', has opened a theoretical horizon to explore the temporal dimension of art practices.

What makes the discourse of 1960s Japan significant is that its construction of gendai bijutsu (contemporary art) not only articulated the sense of contemporaneity as dōjisei but defined postwar art, after gestural abstraction, as a distinct phase of the contemporary (gendai) as opposed to the modern (kindai). This makes 1960s Japanese art a precursor of today's contemporary art. In my methodological proposal, contemporaneity serves as a tool to apply analytical pressure from the periphery on the Eurocentric narrative of modernism in general and postwar art in particular.

Since contemporaneity manifests itself through similarities, a methodological foundation is comparison. Specifically, our comparison is intended to seek out similar yet dissimilar characteristics among a set of similar works, thereby going beyond surface similarities and expanding our local knowledge. By mapping similar works in a spectrum of dissimilarity, we can associate them while contrasting them. Comparison can be made on many different levels, including aesthetics, expressions, and operations, as well as larger contexts.

This last point encompasses the respective art world systems, or, yet on another level, their respective cultural spheres. In a given system, as much as the evolution of its cultural sphere, the development of an art world is highly localised. Multiple modernisms mean multiple stories of how each local system developed and functioned in its sociocultural milieu. These stories often diverge from those in the presumed centre. Furthermore, these local storylines are integral in studying the history of modernism. Other vital yet often hidden storylines include internalised local logics and discourses and international interfaces. In certain cases, artists' individual developments also constitute significant local storylines.

DBThis opens up art into an incredibly diverse field. What are the methodologies or approaches that can guide us through such a field?

RTThis is where I would like to introduce the methodological concepts of 'narrative tangents' and 'contact points' for further amplification. 'Contact point' represents a contact between the Eurocentric narrative and a local narrative, or among local narratives. A contact may be through connection or resonance. The former encompasses actual connections, such as interpersonal and informational encounters with counterparts, while the latter may be formulated post hoc among two or more similar works, where little such connection existed. Connections routinely constitute the basis of transnational art history, but they must be supplemented to factor the contemporaneity of resonating practices worldwide.

Connected or resonated, contact points serve as entry points to the local history and open up the existing master narrative and paradigm, thereby creating intersecting tangents that reflect local logics and contexts. With each contact point, the rigid linearity of the familiar narrative is loosened, with hitherto invisible narrative tangents newly uncovered and bound together like a cluster by contemporaneity.

Eventually, we have to magnify our comparative strategy to seek out similar yet dissimilar yet similar characters. Herein, we decentre, amplify, and regroup at two levels of similarity: while the first level of similarity offers contact and entrance points to the local, the second level of similarity offers a collection of larger frameworks that characterise the 1960s phase of modernism.

DBAnd how might these methodologies play out curatorially? I'm thinking of, for example, the way that you've included archival documentation of The Play's project, Thunder (1977–1986), alongside references to Walter De Maria's canonised land artwork, Lightning Field (1977), which comprises an assembly of evenly placed rods on a plain in western New Mexico.

RTThere are a handful of comparisons included in the exhibition. A comparison of The Play and Walter De Maria is actually the most straightforward because they are a rare instance of pure resonance. They didn't know each other's work, but both projects began in 1977 and both thematised lightning.

In the exhibition context, however, what sets them apart is hard to put on display without the aid of didactic text. Furthermore, the playing field in a comparison between a Western and a non-Western work is uneven, with the Western work often far better known than the non-Western one—that is, in the West, where I work. Or, to use the above figure of speech, the Western work is usually accompanied by an invisible line, such as the narrative tangent, that is already known to the audience, while the non-Western work is no more than a point to them.

In the exhibition, I supplemented the knowledge deficit concerning The Play by presenting a 20-year arc of the group's annual summer projects in a tangible manner. I expected an intuitive understanding to be formulated in the audience's part, so that they would understand the two practitioners arose from two different environments. Still, a didactic text was necessary to articulate the difference between the two works explicitly:

Representing pinnacles of land art in their respective locales, the two works cannot be more different. While De Maria enjoyed the sponsorship of a supportive funder, The Play was primarily self-financed. While the American artist had 400 polished stainless steel poles fabricated and erected, the Japanese collective built their 20-meter pyramid, one rented log at a time, with their own hands. Indeed, they became quite adept at their laborer's task. The strict protocol De Maria requires visitors to follow on a coveted viewing night is contrasted by the open and friendly invitation The Play extended through their posters. Ultimately, their respective goals differed. Whereas De Maria aimed for the transcendental experience of seeing the sublime in nature, The Play aspired for the communal sharing of restorative time while waiting in nature.

The display in the Sky Room, which is outside of the main exhibition space, focused instead on the process documentations to illuminate The Play's communal and do-it-yourself spirit.

Indeed, the greatest challenge for conducting a comparison in an exhibition context is to bring in an operational dimension usually invisible, on display to the discussion. Note, however, that it is also not easy to reference it in writing, as art history tends to focus more on expression than operation. Here, by operation I mean interface and interaction with the outside world. The terminology came out of my study of collectivism in modern Japan, in which I have defined two kinds of artist's labour: expression and operation. Expression typically takes place inside the studio, whereas operation concerns an artist's effort to make his or her work public and otherwise engage society outside the studio.

In brief, the basic principle behind comparison is that contemporaneity (similarity) in expression does not always mean contemporaneity (similarity) in operation.

DBFor many of the artists you study—perhaps most importantly, Matsuzawa—'nothingness' and allied concepts such as 'emptiness', and the 'non-', are not just important concepts but artistic strategies. Can you speak to the importance of these 'negative' approaches in the Japan of the expanded 1960s? What were they a continuation of, and what were they a rejection of?

RTIn my account, 1960s art in Japan unfolded in the expanded 1960s, which ranges from 1954 to 1974, with two dominant tendencies: Anti-Art (Han-geijutsu) and Non-Art (Hi-geijutsu). The spirit of Anti and Non are very much in the air and in action, certainly. However, again, what was at stake at the time must be carefully dissected.

Three practitioners in my book and exhibition give us a good example. In a broader sense of conceptualism, all of them—Matsuzawa, GUN, and The Play—engaged in institutional critique by rejecting or going beyond the conventional system of art-making. Their practices relate to productive negation through which they sought alternatives. In a larger framework, their rejection was aimed at modernism, or what modernity (kindai; also the modern) had engendered. Hence, their assertion of contemporaneity in relation to my own coinage, gendai, in the sense of the contemporary, as opposed to modernity and the modern. This is something that I discuss further in the Asia Art Archive questionnaire on the contemporary.

As for the three in my book and exhibition, they negated the existing system, first and foremost because it did not satisfy their needs: Matsuzawa's pursuit of expressing the invisible invisibly, GUN's frustration with distance from Tokyo, The Play's desire to liberate everyday consciousness from in the complacent trap of late capitalism. They then generated their own alternative sites and methods to pursue their own goals.

However, their negation was no ideology. When the system invited them, they responded in their own ways. Matsuzawa presenting an empty gallery space, and Horikawa mailing stones, both at Tokyo Biennale 1970, and The Play ingeniously brought the wilderness into the museum context in 1971 (Bench) and 1973 (The Bridge). Now, this do-it-yourself spirit is a DNA deeply embedded in the modern history of Japanese art. In that sense, they extended this tradition into contemporary art—I discuss this in an article for Field Journal.

As for Matsuzawa's approach to emptiness, nothingness, or the void, he tapped into a Buddhist source: as he stated in his 1965 work, Void: Collective Participation of 'Anti-Civilization' School, which is presented in the exhibition:

Let us think of the void [kū].

That is the whole character of all the laws.

It is not limited as existence [yū] or nonexistence [mu, also 'nothingness'.]

It is a dormant [myōbuku] state, neither the path of existence nor that of nonexistence.

Yet it is fixed when captured in each moment

If you say it's there and it's not there, if you say it's not there and it's there

DBOne of the key concepts at work in your recent projects is, as the titles would suggest, 'wilderness'. The turn to the wilderness by GUN, The Play, and Matsuzawa, on one level, seems to be a form of institutional critique, since it was a deliberate choice to eschew the exhibition venues of the metropolitan Tokyo scene, although, as you've pointed out, they also did not reject opportunities as they came up.

You have stated that these artists were doubly outside—outside of the West, and outside of Tokyo. Can you speak more to the question of wilderness as it appears thematically and methodologically in these artists' work?

RTThe wilderness, as I conceptualised in my book and exhibition, does not just relate to distant place or nature. That is only one aspect of the wilderness, which is the most visible and the most obvious. The wilderness is a multivalent concept, the essence of which I extracted from these three artists'—and other like-minded artists'—expressions and operations in 1960s Japan and articulated in narrating a local story, although I believe its spirit is not limited to Japan or the 1960s.

The wilderness in essence concerns the artist's mettle—this is not an easy word, but it encompasses courage, ingenuity, audacity, and endurance—to create his or her own space, in terms of expression or operation, in the unknown or the uncultivated, which I called, for the lack of better words, 'out there'. Or, we can call it 'out of the box'. In 1960s Japan, it took a range of forms in conceptualism, because conceptualism, as we came to understand after the exhibition Global Conceptualism [in 1999 at the Queens Museum] is not a matter of style but of diverse strategies to question and destabilise the seemingly unshakable status quo.

DBI was wondering if you could speak to the emphasis on the ecological and environmental within the turn to the wilderness; what were the cultural resonances of nature in 1960s Japan?

RTWith regards to nature, I don't characterise what these three artists did as ecological or environmental, as we understand and use these words today. In their efforts to seek alternative sites, they discovered nature nearby, as opposed to the distant nature in American Earthworks. But I would like to caution against the trap of cultural essentialism. It is true that traditionally nature has been part of Japanese culture. Granted, the presence of nature nearby historically engendered the Japanese affinity with nature. Still, these contemporary artists had to discover nature nearby as a potential site for their new activities on their own, least of all not because that's part of their native culture. Their modes of approaching nature are not traditional at all—that is, not Zen or tea ceremony ways. It's more a proactive approach than a passive one.

I would like to emphasise that these wilderness artists are thinking artists, who think as they work; who think on their feet, as opposed to working from on a set ideology or formula. Their work evolved organically as they tried to figure out solutions to their problems, some of which derived from their distance. Not that they didn't have an idea of their own; they did, but their works reveal many course changes in response to the reality they encountered as they progressed in their works. That's the sign of what I call 'thinking artists'.

DBHow do you hope for the legacy of the radical experiments that you have documented, first in your book, and now in your exhibition, to affect artists working today? And, relatedly, what future curatorial projects are in store for you, if any?

RTA book project in the immediate future is a monograph on Bikyōtō, an activist artists' collective, short for Artists Joint-Struggle Council, which came out of the late 1960s from the politicised campus of art schools. With this group, I go the opposite end of the spectrum: the group conducted institutional critique from within the institution—that is, the mainstreaming of contemporary art. The remarkable thing is that after the political defeat in 1970, when the state government crushed the radicalism that rose around the antiwar, anti-establishment, and student causes, the group shifted its front from politics to art and embarked on a serious experimentalism that examined the end of modernism both in theory and practice.

In the direction of the wilderness, I want to explore the so-called 'final frontier' space. Matsuzawa considered space as his subject from early on. Before he named his home Void/Imaginary Space Situation Exploration Center, he called it Outer Space Situation Exploration Center, and in 1971, he thematised outer space by calling for 'Dark Nebula Plan', in which an individual or a collective would forward their Dark Nebula Plans to him. A variation of his exhibition in 1964, Independent '64 in the Wilderness at Nanashima Yashima Highlands near his home in central Japan, attracted 22 plans. Matsuzawa's cosmic vision was by no means unusual considering his lifelong interest in cosmology, including the possibility of lifeforms elsewhere in the universe, which dates back to his stay in New York in 1957, when he heard the serious and in-depth discussions about U.F.O.s on a late-night radio programme, 'The Party Line'. In his 1986 solo exhibition at Okazaki Tamako Gallery in Tokyo, he created a bilingual work titled Far Away from Earth, the second in the series 'Quantum Art Manifesto 4' (1986). The work was bilingual in Japanese and Ummite, the language of Planet Ummo within the constellation of Pleiades.

I have to tell you that I already did one small intergalactic project with Matsuzawa in 2001, when I included him in Tate Modern's Century City exhibition, based on his biography he published in 1997 in To Spiritualism: Yutaka Matsuzawa 1954–1997, in an exhibition catalogue published by Kawaguchi Museum of Contemporary Art in Japan. According to that, he envisioned having a solo exhibition in 2001 at Lake Iasaaooa on Planet Ummo. So I asked him to share with me a work and show it in the London exhibition, and he generously heeded my request, producing a postcard painting titled An Exhibition of Final Art To Be Shown to the Lake. You know, this made me an intergalactic curator, and to organise another intergalactic project is my curatorial dream.—[O]