Remembering David Goldblatt: Gabi Ngcobo, Jo Ractliffe, & Oluremi C. Onabanjo

In Partnership With Pace Gallery

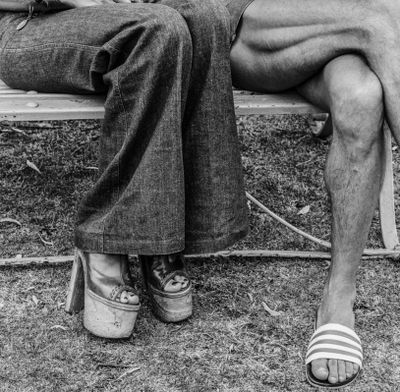

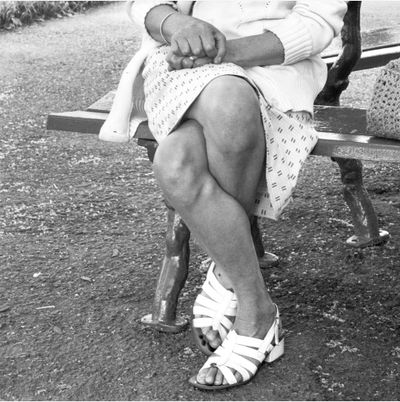

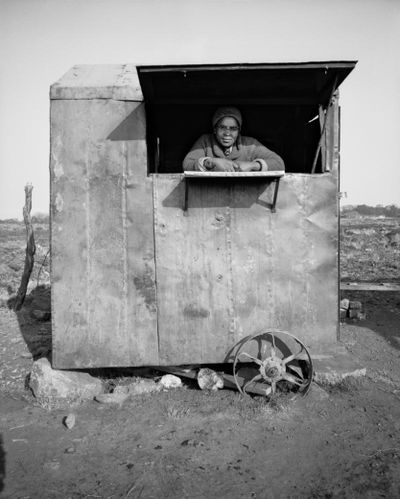

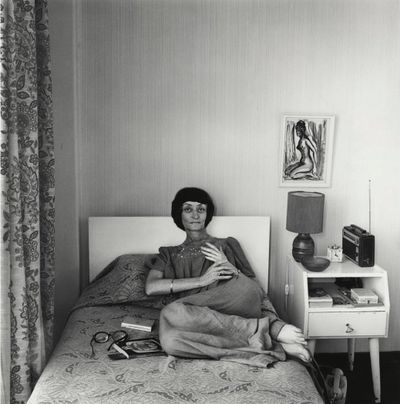

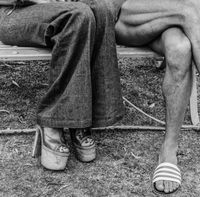

David Goldblatt, At 39 Soper Road, Berea, May 1972 (1972) (detail). Gelatin silver hand print. 27.6 × 27.6 cm image; 40.3 cm × 30.5 cm paper. © The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust. Courtesy Pace Gallery.

David Goldblatt, At 39 Soper Road, Berea, May 1972 (1972) (detail). Gelatin silver hand print. 27.6 × 27.6 cm image; 40.3 cm × 30.5 cm paper. © The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust. Courtesy Pace Gallery.

Curated by Zanele Muholi, David Goldblatt: Strange Instrument at Pace Gallery in New York (26 February–27 March 2021) gathered 45 works selected and arranged from various bodies of South African photographer Goldblatt's work, dating between 1962 and 1990.

The period tracks the height of apartheid policies, culminating the year that Nelson Mandela was released from prison.

Goldblatt is revered for having captured some of the most influential images of everyday life during apartheid. He did so with an uncommon sense of empathy, compassion, and care for his subjects.

As nations continue to contend with their own legacies of racism, colonialism, and state violence, there's certainly never been a time when it felt more urgent to attend the many lessons, challenges, and revelations that Goldblatt's work lays bare.

Zanele Muholi was not only Goldblatt's student, but also a close friend, and this is the first time the artist has engaged with or thought deeply about their mentor's work since his passing in 2018. The show is deeply personal, and in some a ways kind of elegiac meditation on the brutal beauty that Goldblatt's camera captured.

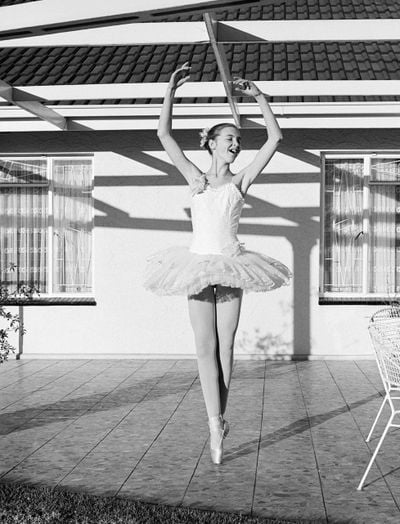

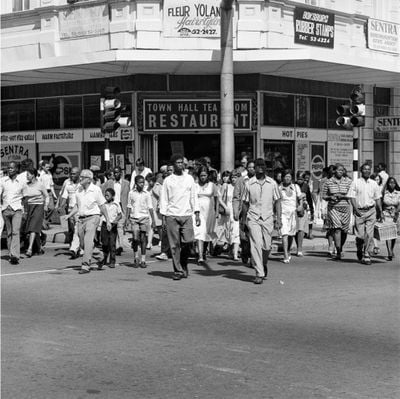

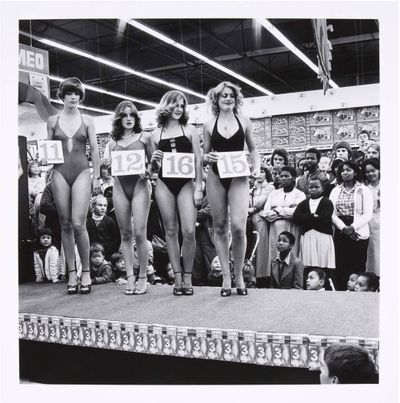

It interweaves his deeply arresting portraits with a wide range of subject matter, from the close-cropped images that he called the 'Particulars', to the landscapes and architectures that he called 'Structures of Dominion and Democracy', subterranean scenes of miners, middle-class white ballerinas and their backyards, and neighbourhoods that would be bulldozed and exist only in the form of Goldblatt's documentation.

All these were places to which what he called his 'strange instrument', the camera, granted some form of access, and the resulting project documented spaces of white privilege in segregated enclaves. It also captured images of black life under conditions of profound oppression, but also mobility and even joy. For Muholi, Goldblatt's enterprise problematises the very question of access, control of which was in many ways central to the system of apartheid.

The following is an edited transcript of a conversation that took place on 26 March 2021, for which photographer Jo Ractliffe, critic and scholar Oluremi C. Onabanjo, and curator and educator Gabi Ngcobo joined Pace Gallery's curatorial director Oliver Shultz, to consider the lives and histories captured in Goldblatt's images, as well as the influence of his work on subsequent generations of photographers and artists working in Johannesburg, South Africa, and beyond.

OSOf the three of you, only Oluremi was able to come and see the show in New York, so I thought maybe I would start with you, Oluremi, and ask if you might share a few of your impressions of the exhibition and what you came away from it thinking.

OOAbsolutely. Being able to go and see the exhibition really did feel like a gift, insofar as Goldblatt is significant to my understanding of South African photography, and photography full stop. He's oriented my thinking, and so to see work that is, for me, emblematic of this practice and really gives us an opportunity to engage with the intersection of social critique and photographic form was really wonderful.

But also, this is Goldblatt through the eyes of Muholi. So this is Goldblatt according to Muholi's categories, including 'On Textured', 'On Poverty', and 'On the Margins'. So it's not necessarily a straight art historical encounter with Goldblatt through the 'Particulars', which is a series that is super close to my heart, or Goldblatt through the photobook In Boksburg (1982) or On the Mines (1973). It's more a reorientation to his vision and the scope of his work. That felt really lyrical and poetic; it was a nice feeling to be able to walk with or walk in relation to Muholi's relationship to the work.

For me, the grace note of the exhibition is the last piece, and it's one category and one image: 'On Segregation, Racial Divides, Beaches Detected Social Distance Before We Knew About It'. That was a moment for me to say, OK, you know, this is the way photography can always speak to our context, and always give us something.

OSI wonder, Gabi, if you might say a few words about your understanding of Muholi's approach to photography as an artist and what it might mean to think of Goldblatt as this sort of canonical figure in the history of South African photography through the very particular interests of Muholi. What does that mean to you?

GNWe're talking about two people who have changed the landscape of photography as we have known it. Since Muholi started with the project in 2005, they were always concerned about representation, because there's power in representation, and they entered the practice from that angle of wanting to see oneself represented in culture.

I have been following their practice from the beginning, through to the projects that they are doing now, including painting, which has been quite an amazing journey to follow. Of course, the shock of moving from photography to painting and just seeing that relationship in an image has been quite an amazing gift.

In the context of South Africa, Goldblatt is a very important figure, mostly with the founding of the Market Photo Workshop, I think, because this has reshaped the way that we have thought about photography, and especially with young women. Seeing the world through the eyes of young black women has been a major shift in an art form that has been so gendered. So when I think about that space, I think about a lot of people.

When Goldblatt had an exhibition at the New Museum in 2009, I was invited by Eungie Joo to put together a panel, which we titled 'Mandela's Ego', which is taken from a book by Lewis Nkosi. I brought together South Africans who were already in New York at the time, to not necessarily reflect on the work of Goldblatt, but also to show another picture in response to his work, and talk about Afrikaans as a language and how it is used in hip hop, especially in Cape Town, but also, the intellectual history of South Africa.

I think it's always important to look at David's lens in relation to other lenses, and I think what Muholi has done is Muholi's queer eye. I think this is what they've been able to do—to queer the archive of David Goldblatt in ways that I have never seen the selection of work put together before.

OSThat was beautifully said, Gabi. I think it draws out so much that is at the core of what Goldblatt was trying to do, but at the same time, in ways that are very counterintuitive or unusual for those that know his careful practice of, for example, giving long descriptive captions that identify the people in the photographs, which Muholi has pushed against with categories that reframe the meaning of the works and bring them into interesting conversations.

Jo, since you know the work and knew David as a person, how did you respond when you saw the ways in which Muholi had engaged with Goldblatt?

JRMy initial response was that I just wished that David were here and in a room with Muholi and I could be a fly on the wall and listen to their conversation. Because he always loved debate and engagement and I think one of the things that he found difficult was that people sometimes weren't critical directly with him. And when I say critical, not simply criticising, but critically engaging with his work.

I remember in my very first encounter with him, the word 'particular' came up in relation to photography and I think that word describes him so well—and it developed over the years. If you look at the early work, the captions are shorter than in the later work, and I think that shows a different sense of relation to what he's photographing and a sense of responsibility.

When I first saw Muholi had disassembled the 'Particulars', I was a bit shocked. The 'Particulars' that Muholi disassembled is now about texture, about being gendered, and is about intimacy—it has floated into very different categories. I think this is very, very interesting because it forces you to look at the photographs in a very different way.

In terms of capturing the ordinariness of life, what Njabulo Ndbele has called 'the rediscovery of the ordinary,' he does that in very beautiful ways, and I think it's in the titling that things become more descriptive.

You can't have the old frame, in a way. It really does invigorate them. But I would be curious about what his response would be. I think he would enjoy the debate. I have no doubt.

OOI love what you said, Jo, about the question of critical engagement, because that is something I see in both Muholi's and David's work—it's the question of engaging and bringing things up to be questioned, to present a tableau and a scene and allow a viewer to engage critically. To see 'Particulars' in all sorts of places seeping through, I think it speaks a little bit to the question of what can be categorised or made the subject of something and then what is everywhere.

JRI think Gabi's point on queering would also be interesting for David. I remember once on a panel at the International Center of Photography, he was starting a series of work that I don't think has ever been published, but it was about photographing people naked. I accused him of having artistic pretensions and disavowing them because he would say that he wasn't interested in aesthetics.

In the panel, and it was part of the performance of our relationship, which was always slightly argumentative, I'd said that he wasn't known particularly for a sensual engagement, that he was seen primarily as an archivist. He got really cross with me and, in fact, referenced 'Particulars', and the sexuality of 'Particulars', and a number of other images.

He talked about those photographs in terms of sexuality, and not simply about intimacy or closeness. I might be wrong, but 'Particulars' tends, in my view, to be received as a kind of formal project, not in the way Gabi describes, which is exciting to think about.

GNYes, I read an interview where Santu is quoted saying that David Goldblatt, who was also the mentor of Santu Mofokeng, is interested in the 'thingness' of things, and he is also interested in the 'not thingness' of things. The poetries are different, but I still consider David's work very poetic, in a way.

I think the way that he's captured people in the parks, the images from 1975, are quite beautiful, which makes a lot of sense when people want to find apartheid in his work and they don't. In terms of capturing the ordinariness of life, what Njabulo Ndbele has called 'the rediscovery of the ordinary,' he does that in very beautiful ways, and I think it's in the titling that things become more descriptive.

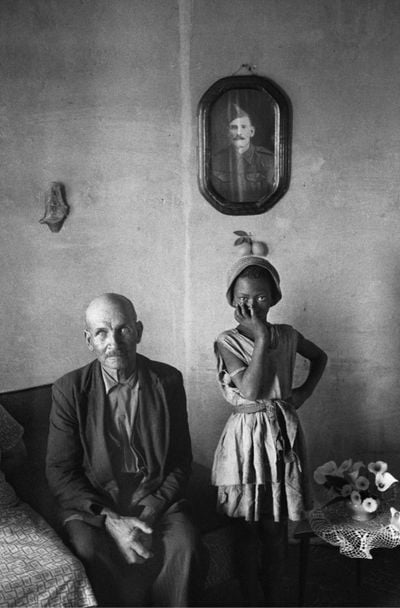

JRIf you look at 'Some Afrikaners Photographed' (1975), it's such a complex, layered, and nuanced body of work. There's one photograph of a young boy with his nursemaid, and he's a young white boy, in short pants, probably 11 or 12, and his nursemaid is a young woman, on the edge of puberty. There's something about the gesture, of the way her hand is on his shoulder and his is reaching around behind her, and he's cupping her heel in his hand. It almost makes me weep.

It's a photograph of such charged intimacy and tragedy because you know where the story is going to go. But there's something so beautifully poetic and nuanced about those tiny little observations that I think is really what is so extraordinary in his work.

He often used to drive me nuts. We would go on a photography trip and he'd come back and we'd look at the work and he'd say, 'What's the point of that picture?' And I'd say, 'I don't know, David, what's the point of the picture?' There would be a roundabout or a swing in a playground, and he would say, 'Look at the ground. Everywhere the ground is loose, but underneath this roundabout, it's hardened. And that's millions of tiny little feet that have been running around in this playground.' And it's that attention to detail that just blows my mind.

OSIt seems like nothing was without meaning for him. He could find social meaning in even the most seemingly background characteristics of a given scene. And I think that's also very apparent in his images of architecture.

In the 1980s, he started to focus on these images of churches, and at one point he spoke about how they were becoming increasingly bunker-like as the world was turning against apartheid, and there was an increasingly global movement. You see the white South Africans hunkering down in these bunker-like churches, and I wonder, too, about how he treated just landscapes and buildings.

He's very well known for his portraits, and maybe a little bit less so for these other kinds of scenes. But for you, Jo, landscape has been very important in your work. I think that the question of landscape and the politics of it are huge. So I wonder how we think about those kinds of images now, as well as not just the images of people.

OOI would say Gabi really got it with the quote from Santu Mofokeng on Goldblatt and the thingness of things. To me, that's where you get to the structures of life that Goldblatt is heralded for, in my mind; where he is able to give you a sense, from a slightly dispassionate, mid-range image, of exactly what is happening in this world, and that can be as structured, brick and mortar-wise, as the churches that you referenced, Oliver, but also the spaces in between.

OSAt one point, Goldblatt was having trouble publishing his work outside of South Africa with magazines that wanted to see documentation of apartheid, because it wasn't explicit enough for them. There was no obvious violence, there was no obvious sort of oppression.

Goldblatt grew up surrounded by gold mines. The land is such a charged figure in South African imaginary, to use a word that's associated with Jo's work, as a place that's constantly a site of contestation and struggle.

Also, in the way he's documenting black communities that are then bulldozed and destroyed, or communities of colour that are bulldozed and destroyed. That feels like an incredibly important function in his work, in terms of documentary practice, but then those images, as has been pointed out, are so beautiful. How do we reconcile the beauty of them with the devastating truth that they reveal?

JRI think certainly with the beginning of 'Structures', but actually even way before, with his photographs of Fietas and the Docrat's house and demolishing of that community, for example. When he started working with structures, I think something crystallised in terms of his own understanding of his project.

He talked about wanting to understand and know the world through photography. With 'Structures', he started talking about values, and there's something about how the values of apartheid are reflected in these structures and spaces in South Africa.

Landscape is such a difficult word, and I wish somebody would find another word for it, but there's something really interesting in the way that these bunker-like churches that you were referring to, Oliver, how they reflect values and movement across the landscape.

My access in the landscape is a particular thing: my work involves driving long distances. And I remember listening once to Santu talking about landscape in his work, talking about a lack of movement, and that the landscape was actually quite a frightening, threatening thing. For me, it was the total opposite. I just assumed that out in the landscape you could be free. It was a big awakening. And I starting to look at that quite early on, and looking at Goldblatt's images, you realise that landscape is not simply 'out there'.

There's one photograph of David's, and I think it's in Leeu-Gamka, one of the Karoo towns, in the middle of driving for miles 'nowhere'. There is a pedestrian bridge that goes over the railway track and there's a barrier separating black people and white people. They would walk alongside each other, but were separated.

It's a detail, you might not notice it, there isn't a sign, but if you really look at the photograph you see how deeply embedded apartheid ideology is. Its project and its enterprise was inflected in everything. Everything! And I think that's why there was no other project for him. It was his way of researching, investigating, trying to understand, being horrified and appalled. His own participation in this was really inexhaustible.

...that's where you get to the structures of life that Goldblatt is heralded for, in my mind; where he is able to give you a sense, from a slightly dispassionate, mid-range image, of exactly what is happening in this world.

GNI feel that there's no photograph that he didn't take, when I look at Goldblatt's work. I used to live in the Central Business District of Johannesburg, and I walked everywhere in the city. And I remember how many times I would encounter a moment or a spot from Goldblatt's photographic history in the city. One project that I really enjoyed, also, is when he went back some years after to the same spots where he had taken photographs in the 1970s, just to show the changes of the city and how Johannesburg became the African city that it is now post-1994.

JRThat's lovely. I mean, that's how he began as well, walking the city.It's how you get to know a place. But it's just wonderful to hear you talk about the way that your experience was framed by an image made by somebody else, decades before.

OSI think that was actually also one of the things that was most interesting to Muholi, too. Thinking about these places that are accessible in a weird way across time, because they're still there and some of them are not all that changed and so many of the conditions of life under apartheid are not gone, or they continue, as Gabi pointed out; especially in the 1990s and 2000s, as so many of Goldblatt's series explicitly attempted to point out, like in 'The Transported of KwaNdebele' (1983–1984).

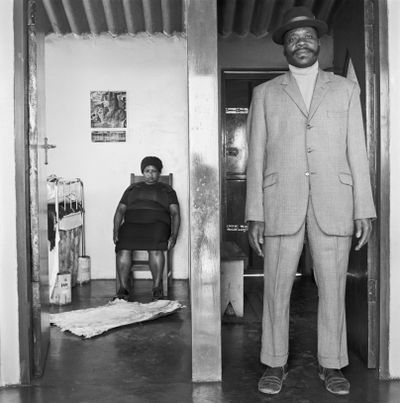

I think that's all so central to thinking about his work. But I want to also think about an image like this, George and Sarah Manyane, 3153 Emdeni Extension, August 1972 (1972), which I think is so extraordinary, not just because it's this amazingly fashionable self-presentation in which he's captured these two individuals in a way that doesn't feel, at least to me, invasive, even though he's coming into their home. But he's also in the photograph, because he's reflected in this central column if you look and see his shadow there.

There's something about Goldblatt's presence in the image here that reminds me that he is, as you say, walking through these—going to these places, going on his bicycle, and physically engaging with the communities that he's portraying.

So I guess that question of access is a really important one, too, for this show and the thorny, ethical questions of when does photography become an invasive or exploitative practice, and when does it become one that grants a voice and a presence to the person or people or things that it's depicted?

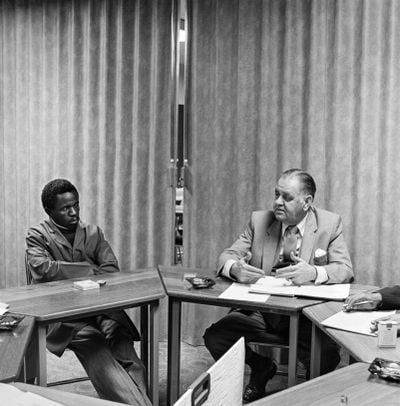

GNYeah, I think you're right. It's really important to think about the economies of access when we think of Goldblatt. Of course, he was a white man in a very divided society and this image reminds me of a project that a young photographer, Sabelo Mlangeni, who also studied at the Market Photo Workshop, undertook in a place in Johannesburg that is called Bertrams, which basically has low income, so-called poor white people around it.

He would go to make photographs in there and it's really interesting to look at this project, because I think there's only one image when he is allowed to come in the house. Most of the people, his subjects, do not allow him to come in. So all the images are allowed, but they are allowed from outside.

I think MoMA owns almost 200 of Goldblatt's images, maybe more. I understood that Goldblatt would go to New York or to many other places and he would knock on the doors of MoMA and they would buy from him directly.

It's important to know that so many other photographers, black photographers such as Alf Kumalo and Ernest Cole, didn't have the same kind of access. Ernest Cole had to change his name so that it didn't sound too African, change his identity, and smuggle his negatives out of the country, never to come back again. He died in New York. Those things are interesting to think about and they're critical.

JRI think he was very aware of that. I think certainly in the 1970s when apartheid so effectively managed to render invisible anything outside of its own interests. One of the things that really interests me, was that David was quite often criticised for standing apart.

During the 1980s, it was a time when there was a real emphasis on collectivity, and David was quite often criticised for standing apart. But Gabi, what you're talking about speaks to his motivation for the Photo Workshop. He was very involved in the beginnings of the Market Theatre and Market Gallery and he started the Photo Gallery.

The Photo Workshop came about after his experience of talking with young black people who came to these exhibitions and were interested in photography, but who had no access. He started classes, initially out of a room in the Market Theatre, and then it developed... Part of it was about people being able to tell their own stories so that their stories weren't being told by people like him.

He had his own story, and he was interested in the intersections of these stories, but I think that's the extraordinary legacy: his contribution of setting up and developing the Market Photo Workshop, and he was involved in it until he died, and that speaks a lot to his engagement and development of photography in South Africa. I think it's quite an unparalleled thing.

GNI almost don't know anybody who was not mentored by Goldblatt, you know.

OSFor someone who doesn't know, what is Market Photo Workshop? It's clearly a school, but it's also much more than that.

JRWell, it started out as providing photographic skills; equipping people, particularly young, emerging black photographers, so they could pursue a career in photography and create some sort of enterprise.

Back then it occupied a small space opposite the Market Theatre, which is all located downtown in Johannesburg, now in the cultural precinct, Newtown. The Market Theatre was quite famous. It began in the mid-1970s, started by Barney Simon, the playwright, and it was a space where black and white artists came together. Ironically it flew under the radar, it seems. John Kani and some of the great actors in this country started out in that theatre.

The Photo Workshop then moved to a different premises across the road, and the programme expanded. It took on exhibition projects, curating, mentorships, and a whole publishing programme.

I'm talking about it in the past tense, but it's actually alive and well in downtown Joburg. And Gabi you're right, he would come in, especially with mentorships and group critiques, and he would be present. There's the story about Muholi knocking on David's door and showing him their photographs and in fact, so many photographers did that.

After he died, we held a memorial at the Photo Workshop—and I'm going to get teary now. I mentored Sabelo Mlangeni during one of the fellowship programmes and I didn't know this at the time, but at the memorial, Sabelo spoke about how David had paid his rent for a year in Bertrams. But it's not simply that kind of monetary generosity, it's also that he would have time for people. That was his gift. He was himself in his work, but he was incredibly expansive in his commitment to photography.

Gabi, you were talking about his access and the resources he had. It's starting to shift with photographers like Santu Mofokeng, for example, but there are still so many photographers—I can list them—who really also need their work to be seen. The commitment of David's, behind Market Photo Workshop, was precisely not to be part of the 'structures of dominion'.

OSAnd much easier said than done, but he seems to have been remarkably successful in that way, and for you to say, Gabi, that you hardly know anyone who didn't in some way touch the Market Photo Workshop is extraordinary. Clearly, it's furthered the legacy of David and his hopes for it beyond maybe what he even would have imagined, which is, I also think, what this show is about too.

It's about looking at his work and finding things in it that are a plenitude beyond maybe what even he himself drew out of it, which was an enormous amount, which is all there for us and yet even more is there as we encounter it now.

As an art historian who's thinking about the histories of photography, Oluremi, in various other contexts in Africa, South America, and in contemporary art more generally, I think it's interesting to think, too, about how the reverberations of Market Photo Workshop impacted the history of photography outside of South Africa, for people who will never have heard of it. That, to me, is quite remarkable.

OOI was going to note, if we're talking about access and circulation, something that I find really important with considering in David Goldblatt's work is the relationship to text and also the photobooks. The photobook-making practice is so significant.

I actually was in conversation with a Ghanaian photographer, Eric Gyamfi, a couple of weeks ago, and we were talking about engaging with photographs spatially and on the page and via a screen, but also in moments of immense social-political turmoil. We discussed what it means to be a photographer, when it's time to put down the camera and start to pick up the pen to write, and we were talking about how Goldblatt and Mofokeng are two photographers who knew exactly how to do that.

They took unbelievable photographs that were socially critical and sensitive, but also had a power of the word and a recognition of how it works in tandem with the image, which you feel in Goldblatt's photobooks, that are amazing and so meticulous. They also were part of a collaborative practice—take his 1973 book with Nadine Gordimer, or even his 2010 collaboration with Ivan Vladislavic. Goldblatt had this sense of understanding not only how to photograph as you see something, but how in tandem with text it gives you so much more.

OSSuch an important point. Thank you, Oluremi, for that, and it couldn't be more relevant to this show and the additional layer of text that Muholi brings to complicate an already very richly complex configuration. As we're coming into our last few minutes of the panel, I want to just invite everyone in our audience to ask questions of our panellists using the Q&A feature on Zoom. A couple have already come through.

Here's one that I think is important. Someone asks, 'Do you think Goldblatt's Jewish background and being partly an outsider and not fully an insider in South Africa contributed to his hyper-awareness of what was going on and his interest in documenting?'

I think that kind of humanism is really informed, but I think he was also deeply aware of his own complicity in things, and I think at times that was something that he really struggled with.

Goldblatt, of course, was Jewish, and he was white, which gave him access to all of these places that if you were a person of colour or a black person, you obviously would not have had access to. At the same time, it's true. He was Jewish. He was in some sense apart from the Afrikaner community.

JRYes, I was chatting with Brenda Goldblatt, his daughter, about his youth. Two of his brothers fought in the war. And growing up in a town, Randfontein, where anti-Semitism was rife, I think he had a real sense of being outside of things and an understanding of what that kind of prejudice could do. I think it really honed his sensitivities, and that does make a difference in terms of an understanding of your place within things.

At the same time in a different context, by virtue of being white, he could occupy positions that are both inside and outside of things—what we were talking earlier on about access. But I do think that it must have informed him.

GNYeah, I think the South African Jewish community, in general, and their role as allies of black people, that can be said a lot in the history of this country. Ruth First, Helen Suzman, many, many people from that particular community who saw an affinity with the struggle of black people in South Africa. These are people you would find in the townships, you would find in so many spaces, trying to show a different kind of humanity than the dehumanising one of apartheid.

JRHe worked in his father's shop and one of the things that Brenda was talking about the other day was the training that he got in that shop, which was a men's outfitters. Brenda was talking about how for her grandfather, every single person who came into that shop was a customer and it didn't matter who you were, where you came from, or what colour your skin was. You were a customer in that shop.

I think that kind of humanism informed his approach, but I think he was also deeply aware of his own complicity in things, and I think at times that was something that he really struggled with. The limitations. It's not an easy position for someone who had his stature to occupy at times.

OSSuch an important point, I think, and I'm glad that you bring up his father and the shop because there's a question from someone asking whether or not his father, being a tailor, helped him see the details, like in the 'Particulars'. I love that question because there is something about the way he cut into the image that maybe is like being a tailor.

JRHe would boast to me that anyone could walk into the shop and he would know their shirt collar size; he would know all of those kinds of measurements. And in fact, I remember once when we were in Vryburg, we bought a gift for the people we were staying with. And there was a young guy at the till, who was trying to wrap this bottle of wine and box of chocolates and was hopeless at wrapping it properly.

David got quite impatient and took it from him and wrapped it absolutely perfectly. I was horrified. I mean, it was impeccable, and he looked at me and said, 'That's my training.'

GNThat's amazing.

OSAmazing, I love that story. Someone asked whether David ever used colour film, and the answer is yes, but not until later on in the whole history of use of colour photography. In a way, we need a whole other panel for that. But it does remind me of something we were discussing, which is the fact that David's work was presented here in an art gallery.

Muholi, of course, has a show right now at Tate Modern (5 November 2020–31 May 2021) and describes themselves as an artist and activist, whereas David seemed to be reticent to describe himself either as an artist or an activist. Yet, I think, clearly he was both.

What do these categories mean for us now? Artist, activist, photographer? I mean, you, Jo, I think, have thought about this and dealt with it, but I think all of you have thought a lot about these kinds of labels and categories that we use. What's at stake?

JRI hate them. I think it's about your intention and the space into which you want to produce. So often these categories are determined by some kind of weird idea of form and aesthetics and binaries that cancel them out.

Years ago, Muholi had an exhibition in a gallery and somebody was being quite challenging, if not critical, about why they were exhibiting in this white cube space. And Muholi's response was that it was a space of activism for them and it was a safe space. 'This is the space where we are not attacked, where our body is not the subject of violence'.

It really is about how you choose your space of production and reception. I don't know what 'fine art photography' or 'creative photography' means. I think if you want to call yourself a photojournalist and you make work for a newspaper, that's great. And you can be a whole lot of those things. That's just my feeling.

OSSomeone is asking, Jo, whether it's correct to say David's work is conceptual? I feel it's post-traditional documentary photography and photojournalism, which I think you just spoke directly to. Of course, it is documentary photography, and in many cases it's photojournalism. Does that make it not conceptual? Definitely not!

I think what we've shown here is that there's no way of disentangling those things, maybe. Maybe we bring our own conceptuality to it as well, that the work allows and offers that, and perhaps that's what's going on with some of these interesting ways that Muholi has suggested we might think about or engage with the work.

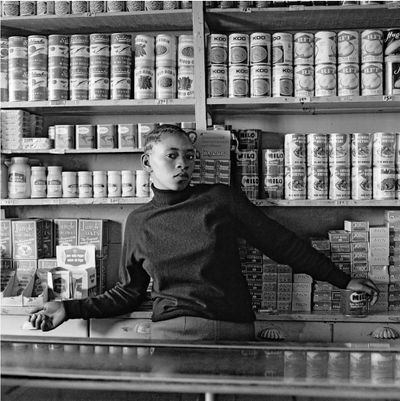

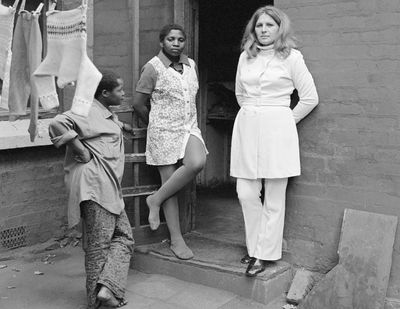

In our very last few moments here, I'll just share for everyone who can't see the show, the first pairing that you see when you come into the show is this, Queen Monyeki in her kitchen, 1388A White City, Jabavu, Soweto (1972) and A plot-holder with the daughter of his servant, Wheatlands, Randfontein (1962) and the category that Muholi gives us 'On Nurturing'.

It's very clear from the first image why you might use that. But then, in the second image, it's much more complicated. This is from 'Some Afrikaners Photographed' series and a very early work. The year before, actually, David closed down his father's shop and basically decided to dedicate himself entirely to photography.

So, there's a ten-year gap between these two images. They're from two different bodies of work. They're imaging completely different kinds of communities. They function in different ways. And yet, when you see them together, what does it mean to think about these both as images of nurturing? That, to me, was a very provocative way to start the show.

JRIt also speaks to the way that he approached photographing. Gabi, you were talking earlier about the threshold of being able to get inside someone's space to photograph. Can I share an anecdote about observing him photographing people? Because I think there was something quite extraordinary in his attitude when he was working on his project on asbestos.

We were in Vryburg where he was photographing people who had asbestosis and mesothelioma. And he was also working with the Asbestos Awareness Group and we went to photograph a man, who tragically died not very long after. The spokeswoman was encouraging the man to grant David permission, making an argument that it would be a good thing for David to photograph him and David said, 'No, this is not going to benefit you in any way.' He was very blunt and direct.

There was something also about when he photographed people: he took time. I sometimes got twitchy in relation to the time that he took, giving people the space to present themselves. But he also waited because when you take someone's picture, the person initially composes him or herself for the picture, in the attempt to present an external self—how you want to look. He wanted his sitters to move past that.

After a period of time, you could see them sink into themselves, in a way. I don't know quite how else to describe it, and he would wait for that. But there was always something very direct in that encounter of photographing people. You see it across the board of the people that he photographed. He treated everyone in the same manner, with the same respect, whether they were young, old, black, or white, whatever their station. And there is something about 'the encounter' that is very striking. And it's in these two images.