Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide): Healing Colonial Adoption Narratives

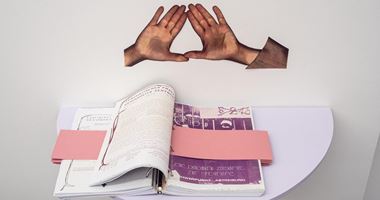

Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide). Photo: POC Stories, 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art.

Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide). Photo: POC Stories, 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art.

Practices of shamanism, the violent eradication of shamanistic cultures by missionaries, healing, ancestry, coloniality, and criminality of contemporary intercountry adoption are the subjects of Sara Sejin Chang's (Sara van der Heide) new body of work currently on view at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art as part of the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (The Crack Begins Within, 5 September–1 November 2020).

Chang's film installation, titled Four Months, Four Million Light Years (2020) is accompanied by 16 textile and paper banners, and a series of watercolours. Built in a non-linear narrative framework, the 35-minute film—which holds a central position in the room—addresses the stories of those forced to leave their families for the intercountry adoption industry.

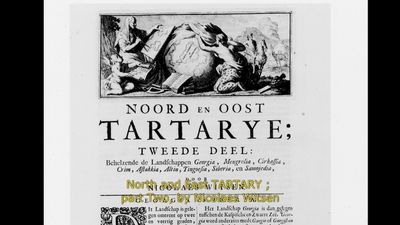

It is 'an embodiment of the stories of many', explains the Dutch artist. The colonial engraving of a Shaman or Devil's Priest (1692) by Dutch statesman Nicolaes Witsen acts as a pivotal point in Chang's research, with texts, songs, shamanic poems, watercolours, and the sounds of percussion connecting shamanic practices with colonial history. In so doing, Chang makes palpable a narrative about contemporary Dutch society, while critically re-reading its historical heritage in relation to the nation's participation in the Korean War (1950–1953) and the colonial descriptions of Asian people that it may have produced and circulated in the past.

Framed as part of the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Chang understands the project not only as an invitation to display her art, but as an opportunity to investigate the cultural and intellectual context that gave rise to the many ghosts of motherhood. Within the broader context of the Biennale, Chang envisions the installation as a contact zone with artistic practices and histories that go beyond those that she has been able to include in her work, namely with the contexts of Belgium, the Netherlands, and South Korea.

Four Months, Four Million Light Years follows on from Chang's ongoing project The Mother Mountain Institute (2017–ongoing), which collects and brings forward the stories of mothers from the Global South whose children are trafficked today for intercountry adoption.

First presented in 2017 as part of the exhibition To Seminar at BAK – basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht (11 March–21 May 2017), The Mother Mountain Institute focuses on the women who have been erased and silenced in the global adoption industry. The project's first iteration at BAK was composed of an installation, drawings, and sound focusing on the story of a South Korean mother. Situating the life of the birth mother within the constellation of the international and interracial adoption system, Chang created a large wooden enclosure painted to represent the solar system, with two spheres hanging overhead and rotating within the space, representing mother and child as the sun and moon.

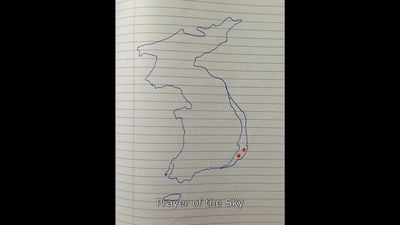

Chang's work traverses an array of formats and mediums, including drawings, installations, performances, film, and interventions. In The German Library Pyongyang (2012) project, first presented in Amsterdam in 2012 at the Goethe-Institut, followed by the 1st Asia Biennial / 5th Guangzhou Triennial in Guangzhou (11 December 2015–10 April 2016), and later the 6th Kuandu Biennial in Taipei, Taiwan (5 October 2018–6 January 2019), Chang recreated the German library originally opened in Pyongyang by the Goethe-Institut between 2004 and 2009, under the claim that it would help North and South Korea with the unification process through Bach and German literature.

Performing an imaginative journey to North Korea built on fiction and history through artistic, linguistic, and graphic interventions, the installation explored the imperialistic notion behind German libraries and learning centres, promoting German culture and values.

With repetition and insistence, Chang considers different angles of Eurocentric thinking and its penetration in all levels of life and society. Her artworks attempt to deconstruct the institutional bases of power, wherein objects, groups, and individuals are codified, managed, and selectively oppressed according to predetermined notions about their race, gender, and class.

In the film Brussels, 2016 (2017), which covers the period surrounding the terrorist attacks in Brussels and the Brexit referendum, Chang uses the format of a letter to address her mother in Korea, recalling her experience in the city at that time, as a resident at WIELS – Centre for Contemporary Art. Working with multiple registers and individuals inside and outside the institution, Chang sketched a poetic and political portrait of the Belgian capital.

Rather than mourning histories and personal trajectories, Chang is fascinated by how the past might be reanimated in the future. At the core of her project at the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art is a concern with how ideas are transmitted from the past to the present; from the dead to the living.

KBYour film installation Four Months, Four Million Light Years (2020) premiered at the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, and will be showing next year as part of Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Brussels (7–9 May 2021). How did it originate?

SSJAt the end of 2018, I felt the need to create a new work on my own terms, without a deadline, venue restrictions, or an overarching curatorial framework; without knowing, even, whether the work would ever be shown somewhere. The idea for this new work had been with me for some years, but I had to find the confidence, the right words, and the time to explore it and implement the project.

When I started Four Months, Four Million Light Years, I wanted to work without constraints. I think it is so important for an artist to reclaim this space, to have the freedom and time, with no deadlines, to experiment and conceptualise, whether that be writing, mixing colours, filming, making music and sound, or rethinking ancestry, place, and belonging in contemporary society. In a way, what you kind of imagine as a child what an artist does. Eventually, however, deadlines and the pandemic did kick in.

I wanted to speak about adoption, and the parts of life that exist before adoption takes place. Parts that are violently being erased, when individuals are being adopted to a white Christian secular country, for example. Intercountry adoption is still seen as an improvement by many, as if these children have been saved, without acknowledging the damage and loss to both the adoptees and their respective mothers. Young, vulnerable black and brown bodies that are taken from their families and environment, often by white families, and moved from country to country. For the sake of what?

I think it is so important for an artist to reclaim this space, to have the freedom and time, with no deadlines, to experiment and conceptualise...

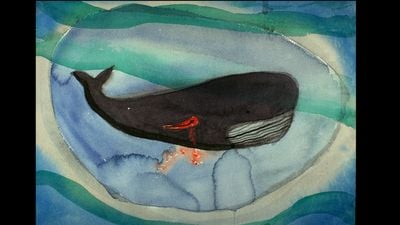

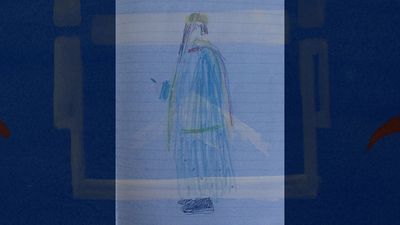

I wanted to find a language to speak about the unaddressed trauma that often goes with adoption, without victimising the adoptees. Without knowing the structure, form, or materiality of the work, I knew I had to make it. In my dreams and throughout time, I received messages and visions to go forward. A recurrent vision was of a painted reality depicting ancestors in very vivid colours. These visions were a bit strange, as they were clearly alive, yet timeless and painted full, with the most beautiful details and colours. So I knew I had to make watercolour paintings and project them. Colours and watercolours have always been very present in my practice.

I was born in Korea and have returned several times. In the 1970s in Korea, intercountry and transracial adoption reached its peak. Every year, thousands of babies and children went overseas to white families in Western Europe, the United States, and Australia. In response to high demand in the West, two to three hundred thousand Korean babies and children were sent for adoption to the U.S. and former allies of the U.S. after the Korean War.

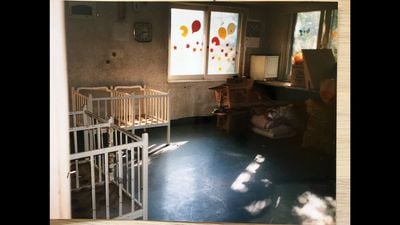

At the time, there were already signals to both the Korean and European governments that on a large scale, children were disappearing from Korea. Mothers were pressured to sign papers to relinquish their children, enabling the falsification of papers and child trafficking. In 2018, the orphanage told me that a law had been implemented to protect children and to prevent babies and children from disappearing in the illegal adoption system, without the consent of the mother and family.

This law stated that the children had to stay for at least four months in an orphanage before they were eligible for adoption. If no family member claimed the child after four months, they would be eligible for intercountry adoption, which involved a lot of money. This law seems a good measurement, but in reality, what happened was that babies were placed directly in orphanages after birth, without the knowledge of the mother and family. Often, young women were unaware that their children were still alive, or they were told that they were unworthy of keeping their child, or that their child would be much better off in adoption, and there is no maternal care or support.

Middlemen in the adoption industry tried to bypass the four-months bill by placing the babies in orphanages, without their mother, family, or the care they needed at a crucial time in their development. Babies need their mothers or direct family to regulate their emotions, as they are unable to do this by themselves. After four months, babies were then available for intercountry adoption after being exposed to high levels of emotional neglect and psychological trauma.

Those babies had already been exposed to the largest loss in their life—the loss of their mother and family, to whom they belong. The parameters are different, but the narratives are the same: countries that have been destroyed and plundered by imperialistic wars or colonialism are today suppliers to the adoption market of the Global North.

In adoption seminars and while speaking with researcher Chiara Candaele, a PhD candidate at the University of Antwerp, I was told that it is safely estimated that millions of BIPOC babies and children have been taken from their original families and adopted by white families. This was part of the global European civilisation project, of Christianising 'the savage'. I used my own position as an artist to highlight that it is important to discuss what the colonial narratives are around intercountry and transracial adoption, leading to new legislation and treaties, as clearly the treaties have failed.

KBCould you talk about the different narrative threads you bring together in Four Months, Four Million Light Years?

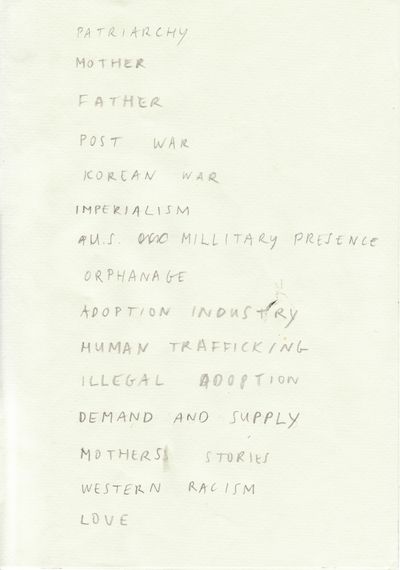

SSJI wanted to bring several threads together: shamanism, the violent eradication of shamanistic cultures by missionaries, healing, ancestry, the coloniality and the criminality of contemporary intercountry adoption, and also the current position of BIPOC adults with adoptee backgrounds in Western society.

As an artist, I am interested in forms of imagination and language that carry us to other realms of understanding.

Throughout my life, I have been drawn to shamanism and animism. In November 2018, I was in Korea and I had the great opportunity to meet Kim Keumhwa (1931–2019), a mudang, or female shaman, recognised by the government as the lineage carrier of Korea's Important Intangible Cultural Asset, who told me that if I had not left the country I would have become a mudang. She said that it is my destiny to be a shaman, but that it's fine that I have become an artist and that I fulfill my role in life in this way.

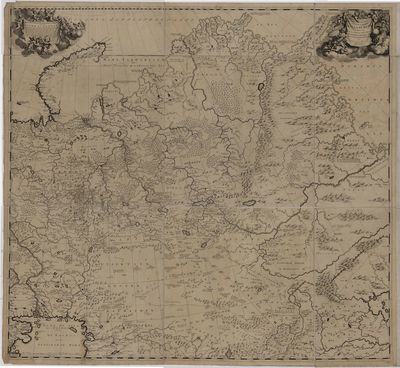

For me, it was important to go to the source of these narratives behind adoption and to give a face and forms to these invisible but powerful structures, that have and continue to have a dramatic impact on so many lives. One of the first Western images of a shaman is by Dutchman Nicolaes Witsen, Een Schaman ofte Duyvel–Priester (Shaman or Devil's Priest from the Tungus) (1692). The print is part of his extensive encyclopaedic study on North West Tartary—current inner Eurasia. In my visit to the Darkhad Valley, in northern Mongolia, I filmed the same site depicted in the print.

The publication was made to gather information on the region, its flora and fauna and people, for economic purposes, to see if these locations were suitable for Dutch lucrative trade—the start of destructive and shameless capitalism. Nicolaes Witsen was at that time governor of the Dutch East India Company. Together with the Dutch West India Company, the Dutch formed one of the most powerful imperialistic powers.

Growing up in the Netherlands, we learned that this violent time was called the Golden Age. Colonial images of people and cultures, that continue to be reproduced over centuries to eradicate shamanistic cultures, and where men and women of Asian descent were portrayed as inferior, infantile. Growing up in Western societies, this is the environment that adoptees of colour are exposed to. The paradox is that almost all intercountry or transracial adoptees come from animistic and shamanistic cultures. In the West, these cultures are perceived as uncivilised.

The film is maybe a reflection of my own brain: connected to several localities, ancestral visions, and methods of research, using historical sources and footage. But at the same time, the structure is set in an animistic and ancestral cosmology where linear time is dissolved. I would say that the film is structured in such a way as a CD, bringing together different songs, each having their own tone, melody, and rhythm under one umbrella.

Undoing Eurocentric hierarchies in terms of what is meaningful, or what is a reliable source of reference, is something that I love doing. This is a common thread throughout my artworks, but at the same time, I appropriate and unravel these methods, and by doing so I give them alternative meanings. I follow the rules of the documentary format, but at the same time I play with the structure and linearity of film.

The process of healing manifests itself in building a community and reaching out to people who have made the same journey.

For the film, I wanted a psychologist to explain the trauma that is caused by separation in order to make a child adoptable. Miranda Ntirandekura Aerts is a clinical psychologist and an adoptee herself. She is a powerful voice in the adoption debates happening here in Belgium, where she is part of an expert panel, where malpractices related to adoption are currently being investigated. Miranda and I often speak about how we can empower our positions as adoptees, as so often it is our family, strangers, and society who speak for us.

It was important to ground the work in the here and now, and to bring in several voices. There are moments in the film that are clearly rooted in the present, and embrace more scientific methods. As I don't speak or read Korean, for the Korean shamanistic part I depended on English sources on Korean shamanism and I reached out to friends and my network for support.

Initially the plan was to go to Siberia and northern Mongolia—where the first image of a shaman was depicted by Nicolaes Witsen, and where the Tungusic peoples are spread—and also to travel to Korea to ask Korean mudangs for a healing ritual, but because of the pandemic, I couldn't travel to Korea. Then, here in Belgium, I worked together with other Korean-Belgian adoptees to create songs. Lisette Lagnado, one of the four curators of the 11th Berlin Biennale, with whom I worked closely, described it as the following: 'One can feel a personal, but collective voice coming from a nation of children'.

KBThe layered quality of your film stems in part from the mix of archival footage, projected drawings, and scenes you've shot, including lots of natural imagery—forests, mountains. How does the natural environment figure in the intellectual and cultural contexts that are the focus of your research?

SSJIn most countries, people know that we have to listen to the earth. We inhabit the planet together with plants and animals, big and small. It is not the size of the brain or the size of a sentient being that matters, what matters is that we are part of one cosmology. In Korea, the mountain is seen as a bridge between the gods and the earthly world. Mountains, oceans, and lakes are seen as being wise beings, in their own ways. There is this deep sense of connecting, reading, and feeling the landscape.

In shamanism, the drum, voice, or other rhythmic sounds are often used as vehicles by the shaman to 'journey'—to connect with the ancestors and spirits. One could see the entire film as one shamanic journey or lullaby. That's why sound plays a prominent role throughout the film.

Apart from working with traditional Korean instruments, chanting, and songs, I also invited Belgian contemporary sound artist, Céline Gillain to bring the work more into the present and future. Together with Yan Vandenbroucke, who is a Korean-Belgian singer, we created two new songs: the first and the final song. The first song is in Korean, where the child says goodbye to their father and mother, supported and surrounded by ancestors.

KBIn the film, we travel through different timelines and spaces. You engage with buildings, places, sounds, and spirits both physically and viscerally, subjecting yourself to different valences.

How does travelling impact your observations on distance and communication? Did you reside in the various locations as you created the film, or just visit to shoot the film?

SSJThere are different methods of travelling: physically, spiritually, and with the internet. And in this film, there are no limitations to the means of travel: we travel on the spiritual plane, through Google Maps, a shamanic drum, and also real airplanes. There is no hierarchy in this.

Often, an unwilling rupture is at the core of the migration of adoptees, in relation to their family, culture, or land. Even when they don't know their bloodlines or are disconnected from family, and not physically living in that country anymore, it is painful, because the question always comes up: where is my family, and how does one connect with a culture one feels so alienated from, by not speaking the language, and so on?

The word 'adoption' is related to the word 'adapting'. Adoptees have to adapt themselves so much to their new family, and also a new country. In order to fit in, the brain literally disconnects with the memories related before adoption. Studies show that after adoption, children who were able to speak Korean and were adopted at the age of six, are no longer able to speak the language, as memory is connected with language.

As I mentioned before, my initial impulse was to travel in the spring of 2020 to Korea and learn rituals or ask if mudangs wanted to perform a ritual together with me. But because of the pandemic, there were a lot of unforeseen events. I decided to move on without actually going there and to find a way to work around that. In the end, I realised it wasn't necessary to go to Korea. I had access to a lot of Koreanness through distance, through books, and via mudang Jenn, who is based in New York City and is generous with sharing knowledge.

It can be healing to realise that there will always be the guardian spirits for you, who have travelled with you since you were born. Everybody is born with spirits alongside them. There are often ancestors who surround you, even when you are not aware of them. Once you connect with them you can work together and ask for support, without actually being in your country of origin.

Undoing Eurocentric hierarchies in terms of what is meaningful, or what is a reliable source of reference, is something that I love doing.

I was not interested in exoticising Korea, or making a traditional film. I wanted to make a film with and for the global adoptee community situated in the here and the now. I realised that it is not necessary to be physically present to heal. The process of healing manifests itself in building a community and reaching out to people who have made the same journey. The film is not restricted to Korean adoption; it reflects the stories of adoptees worldwide.

Lila John created these beautiful costumes, for which we looked at traditional Korean costumes, so this echoes through, but they are our interpretation of robes we perceived as suitable. We used a lot of golden fabrics and other colours different to the white, red, blue, and pink dresses the mudangs wear.

I respect the elders of the mudang community and their traditions, and I would not want to claim to be a mudang, as I have not received initiations. I received shamanic initiations and teachings here in Belgium. I did feel authorised to create ancestral songs with two other Korean adoptees.

In Korean, tradition shamans sing healing songs, while the ancestors sing through them. So the film starts with that moment. It starts at the moment before a child is born, and still resides in the sphere of Light, and the ancestors are speaking to him or her before they are born. And then we go to the Korean War, the imperialist war, which involved many European soldiers, including Dutch soldiers.

From the Korean War, we travel to the present, and Miranda Ntirandekura Aerts speaks about the psychological experience of adoption, filmed here in Brussels. This is followed by the historical journey back in time to Dutch colonialism and missionaries—the historical framework within which intercountry adoption takes place. Then the healing journey starts. We journey through the drum of the shaman, depicted and described by Nicolaes Witsen in 1692 as a devil priest, to the land where he was depicted, in current northern Mongolia, and where I went in December last year, just before the world went in lockdown.

It was minus 35 degrees Celsius in the Darkhad Valley, in northern Mongolia, where I travelled. Witsen marked the 'white salty lakes'—current Tsagaannuur—on the map at the end of the 17th century. I had the opportunity to stay there for two weeks and meet the elders, who performed healing ceremonies. We drove over the frozen lakes, and at night the stars were so incredibly bright it felt as if you could touch them.

During Christmas, the family I was staying with watched The Exorcist (1973) on a post-communist national TV channel and drank Coca-Cola, it couldn't be better! The shamans I met come from an unbroken lineage that is thousands of years old. They live with the spirits of the lake, the mountains, the land, the stars, and the animals. The shamans are considered as very powerful, they are welcoming, but also very conscious of spiritual tourism and are protective of their knowledge, as some Western neo-hippy charlatans have shown up and messed around with traditions and spirits, bringing themselves and others in danger.

KBYour approach is both imaginative and poetic, and at the same time you develop a strong historical context that is often lacking in discussions in Euro-American contexts about the Korean Peninsula. You clearly move away from the personal to focus on collective stories around transracial and transnational adoption, specifically the historical relations between the Netherlands and Korea.

Could you talk about your choice to not speak from your own perspective, using a neutral voice both conceptually and in the film's narration?To what extent do you consider Four Months, Four Million Light Years as a political project, triggering discussions around reclaiming the narrative of healing?

SSJThank you for this one. I don't believe in a pure academic understanding of the world alone, the intrinsic hierarchy that comes into play, and the disenchanted world it has created. Empirical studies are important, and it is incredibly urgent what Elvira Loibl brought together in her extensive research, The Transnational Illegal Adoption Market: A Criminological Study of the German and Dutch Intercountry Adoption Systems (2019). It is a meticulous study and it shows the criminal mechanisms involved in adoption, and it confirms what adoptees have been telling for decades.

As an artist, I am interested in forms of imagination and language that carry us to other realms of understanding. But the key to understanding and relating to one another is being able to see and understand the joy and pain of others, outside ourselves, and the capacity to see what we do to others and to ourselves. To transfer or deal with these raw emotions.

Four Months, Four Million Light Years addresses the pain, the loss, the coloniality of transracial adoption, white saviourism, and the healing journey adult adoptees have to go through. For many non-adoptees, the complexity of the related emotions and politics is unfamiliar, and it was wonderful to receive the feedback in Berlin from non-adoptees, who were grateful for what they learned from the film about intercountry adoption. I have also received feedback from adoptees who are appreciative of their story being shared with the public.

I felt it was important to take the time to research the form and my presence in the film. I was not interested in making a personal story about myself. It is the voice of a collective, or the story of 'a Korean-Dutch adoptee'. I am present in the work, but so are many others. The film is an embodiment of the stories of many.

It is also a principle of protecting myself, as it is a political decision to not include myself and my own story that much in the film. As an Asian diasporic woman in Europe, your body and story are exposed to the most ridiculous, diminishing, racist, sexist, and invasive projections, assumptions, and questions. The designated area where you can operate as a Dutch-Korean adopted queer woman of colour is still determined by others for you.

The identity and meaning of my work finds itself beyond these restrictions. My work and those structural restrictions are what I want to talk about. When I have to answer the question about whether or not I have found my mother, the one who asks the question does not have to consider their own position or think about the urgent questions I am raising through my work. I am not interested in becoming the subject of pity.

Through my artistic work, I want to return the responsibility of this violence and refuse the invitation to be subjected to highly problematic and racist norms. There is an oppressive framework at play in describing the work of BIPOC artists as 'personal' and subjective, continuing the process of othering and seeing BIPOC as 'savage' and irrational. When is the work of an Asian diasporic woman being perceived as 'neutral'?

In the process of healing, it is important that policymakers, caretakers, and friends enable themselves to take the position of listener and learn from the experiences of adoptees. There is so much knowledge through our lived experiences to take the debate around adoption, Western fertility problems, and global asymmetries to the necessary next level, in order for there to be change.

From an early age, adoptees have been embodying the narratives of others, and it is extremely important that they get a chance to develop their own narratives and methods of healing. It is okay to make room for a lifelong sense of loss, and each of us has to find our own way of dealing with this.

KBHow would you place Four Months, Four Million Light Years in relation to the broader narrative of the 11th Berlin Biennale? I understand that the title, The Crack Begins Within, are words borrowed from poet Iman Mersal, who explores the many ghosts of motherhood, tearing apart its contemporary morals.

SSJThe film installation Four Months, Four Million Light Years is presented in the themed chapter, 'The Antichurch', at the 11th Berlin Biennale. The curatorial statement is both poetic and powerful. Rather than questioning whether necessary transitions or transformations are happening, it suggests they are already here.

From different angles, forms of colonial patriarchy and the influence of the Church are being dismantled. Systems of care and love, kinship, healing methods, and motherhood are presented. I share the third floor of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art with artists who each have their own very strong visual languages, and we share this imaginative part.

I love working like a scenographer, playing with light, darkness, colours, and creating an immersive installation that transforms or invokes a different world. For the 11th Berlin Biennale, I created a shamanistic room. It is an immersive installation where you hear the rhythm of the drums, the voices, lullabies, and songs together, while viewing the drawings and the banners, calling upon the ancestors.

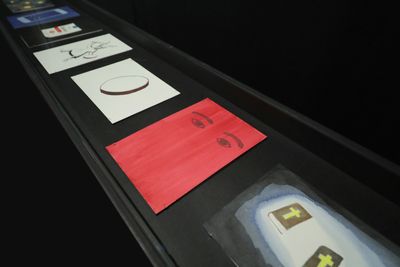

In Korean shamanism, each colour has a different meaning, referring to the several elements we are all made of. The film projection is in the front, accompanied on both walls by textile banners. On the opposite wall, there are two vitrines showing watercolour paintings. The paintings here are presented in object form, and in the film as fluid visions.

I like working with watercolours—the colours have a luminosity, vividness, and weightlessness that resembles dreams or visions. Yet you can also achieve realistic, photographic moments with them. In the film, the watercolours portray the past and what is still here. The ancestors are not dead, they are still here; objects are animated and time is dissolved. They are my observations and insights.—[O]