Sarah Sze: The Importance of Impossible Ideas

Sarah Sze. Courtesy Sarah Sze studio and Gagosian. Photo: Deborah Feingold.

Sarah Sze. Courtesy Sarah Sze studio and Gagosian. Photo: Deborah Feingold.

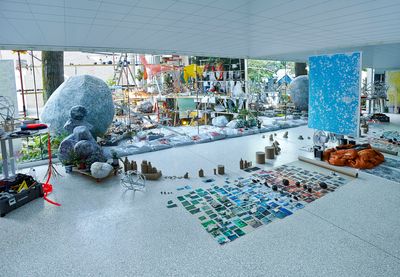

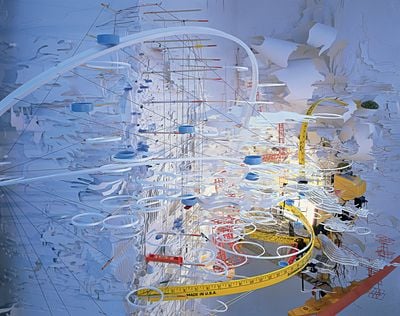

Sarah Sze's installations thrive at a tipping point. Frequently rendered to magnificent scale, they are made up of skeletal structures supporting a cosmos of matter: matches, buckets, dried paint, plants, and paper, to give but a sample of the elements frequently assembled in their orbit.

From afar, these structures tremble with precariousness—a feat of engineering that can be attributed to Sze's training as both an architect and a painter. Sze refers to herself as a sculptor, however, and at the heart of her practice is a concern for physical matter, which she feeds back as careful agglomerations reflecting the fullness of lived experience. There is, at the same time, an edge of loss in the promise of full experience: Sze's installations never can really be experienced in totality as a result of their vastness and extraordinary detail, which is a quality she attributes to the digital experience, and the sense of longing that comes with navigating information and images online.

Her latest installation, Plein Air (Times Zero) (2020), which opened at Gagosian in Paris on 18 March, has more explicit references to loss. One example Sze cites is after the death of her great aunt, she was invited to pay her respects by lighting a candle on a dedicated website, leading her to question the complexity of memorialising a human life in virtual space, and 'how much is lost in not hearing the strike of the match; seeing the smoke rise and the drip of the candle.' The crackle of a flame fills a dark room at Gagosian, where projections of disparate images flicker around the room like a mobile—the trickle of honey in one; an airplane moving across the sky in another. It is an invitation to open discovery, offering an experience of quiet contemplation, with each image adding to the viewer's internal world.

Sze's latest paintings have been created as portals, also. An image of a road beneath a vast, open sky has been shattered by elements in oil, acrylic, pencil, graphite and more in Ripple (Times Zero) (2020), for instance, suggesting a moment of total obliteration, where fragments can give way to new forms. While ushering us to see the world anew, Sze also brings us back to the materiality of painting, which she suggests holds added significance in the annihilation of the physical world in the digital age. It is a question that has become more prevalent in recent months, when life has shifted online as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, and perhaps in the starker consideration that 'big tech doesn't build anything', let alone basic necessities such as medical equipment, as David Rotman argues in a recent article in MIT Technology Review.

In this conversation, Sze discusses the threshold between digital and lived experience at play in her work, how art functions as a record of its time, and the importance of impossible ideas.

TMIn your practice, you set up dialogues with the physical world so that viewers can re-experience it in a new light. Painting—a medium that is fundamental to your practice, and that you return to for your exhibition at Gagosian in Paris—offers an immediate translation of the physical world, whereas your latest installation, titled Plein Air (Times Zero) (2020), is a multimedia installation that re-presents images from the world in a transformational state. It is conceived as a 'portable station for the interchange of images and the exchange of information,' to quote the press release.

As the world shifts online as a result of the coronavirus outbreak, and people turn to their own 'portable stations' of mobile devices and computers, I wondered what your thoughts were on this digital shift in relation to your own work? I'm thinking particularly of how you deal with notions of time and continuity—two themes that are facing the greatest interruption in recent history.

SSI think you're absolutely right—the disruption of time and continuity right now is going to be a historic and abrupt edit and cut in everyone's lives, in the way we measure time and space. Textural experiences are one of the biggest ways that we record memory and time, and everyone's measurements of that are very strange right now.

That confusion between the digital experience and what is happening in a specific time and place has been of interest to me for a while. The title of the sculptural video installation in Paris, Plein Air (Times Zero), is a reference to the experience of reflecting on life in situ. I started as a painter, and in some ways, I think the show represents a return to painting, and in others, I think it's actually really been the backbone to all of my sculptures from the beginning. When I've used sculpture, I've been less interested in the object than the relationship between objects, which is a fundamental filmic idea, starting from Sergei Eisenstein and how the metaphoric can arise through the juxtaposition of two completely disparate images to make meaning. In the age of the image, a painting is a sculpture, and it becomes even more of an incredibly lush experience, because we're so used to looking at many things through digital colour spectrums, whereas two centuries ago we perceived colour differently because we didn't have those processes.

In my paintings, I'm trying to use a palette that draws from this elaborate spectrum of colour that we now have available to us and that we're reading all the time when we're juxtaposing the screen and nature, in a complete flow of unedited information. That onslaught of images and how it affects the way we introspect with the textural complexity of seeing and experiencing real life—that edge is really what I wanted in the show. Much of the thinking around that is impoverished by the idea that the two are separate. There's a materiality to the digital, and alternately, the way that we experience the physical world is affected by how much of the digital we are seeing.

TMIt's interesting to think about all of this in relation to the museum and gallery exhibitions that have been moved online in recent weeks. Have you had to consider at all what a digital experience of your work might be like? Is that a hideous proposition or an exciting one? What challenges might that pose, particularly in relation to the experiences of micro versus macro at play in your work, along with viewers' sense of orientation?

SSThere are so many complexities, but for me I've always thought of the digital as a medium in and of itself. I've always been interested in what any medium does well or poorly that another one doesn't, and to play with that across mediums and with the idea of gravity. A lot my sculptures use gravity in ways that are intrinsic to the properties of sculpture. In painting I think about, of course colour, but also the potential of the frame; of the image of flatness and space; of figure and ground, and how to break that down in new ways, but in ways that are so intrinsic to painting. When I work with the digital, I'm interested in how it deals with time—with the asynchronous and the synchronous, and has a way of blending our real and imaginary worlds. It has a way of slipping into our inner images and confusing those with the outer. As a medium, it degrades, changes, and mutates faster than any other medium I work with, and is organic and fragile—though people don't often think of it this way—and in flux intrinsically.

In regards to the challenge of trying to experience an artwork that is meant to be experienced in life but has to be looked at digitally, what's interesting is to see what we can learn about it that we couldn't learn by seeing it in person, and to really focus on that potential in the reception of a work digitally. For example, to show someone a painting, but then to guide them into detail as to how that painting was made, and maybe the history or the references of that work—that's what's interesting about seeing an artwork presented digitally, because you can reveal things that you wouldn't have in real life. Of course, the things that you have in real life are spectacular and could never be replicated and we just have to assume that when you see something digitally and then when you experience it in real life, there's going to be this shift, a shift with any strong physical artwork that is additively spectacular—that you're not disappointed because it looked better online, that it is textured and based in the moment and its physical presence is transformative. The additive experience of digital information can allow you to understand an artwork in a different way.

The challenge now is to try and figure out how to make the digital textured—how you can reveal complex layers of information to show the history of references that you're trying to make or that have affected you in the making of the work. I do think that art—even online—provides what it always has, which is sustenance and a real reflection on what is happening in the moment it's created.

Throughout history, artists have worked through crises, and I think an artist in many ways always makes the record of their time, and of the humanity in their time. What I'm trying to help my students at Columbia with is to process what it is to be human in this moment. What it is to be human in this moment is so surreal, and so extreme, that the work that could come out of it—even if we don't understand what we're making as artists now—could be such an interesting and important historical document. We have literally walked off a cliff—we're in freefall, and we'll only understand it in retrospect.

To heighten the senses is the medium of any creative work.

TMThinking about works as records of their time, your Public Art Fund commission for LaGuardia Airport will be unveiled in a whole new light, when people begin travelling once more after months of global lockdowns. Has this global situation given you any new perspectives with regards to this project? Has it shifted your thinking around public art in any way?

SSFor LaGuardia, because it is a public transportation construction site, the art was designated as 'essential' and as an artist, I was an 'essential worker' during this time of the pandemic. It was interesting to reconsider the urgency of art in society in this context. From the beginning, I've always had a commitment to trying to bring art to the largest possible public, to make it accessible to all. The minute something is a public project, there are so many logistical and structural things that limit what you can make as an artist, but it is very important that part of the conversation is about pulling work from inside the museum or gallery and into public space. Bringing work to an audience who may not even recognise a work as an artwork—but that becomes part of the collective conscience in a more fluid space—that has always been really interesting to me. It's a privilege when you make work for a public space, you can talk to a larger audience about the experience of an artwork, and you can also have it be part of a daily moment.

LaGuardia as an airport is a portal—it's a location where you're in this disorientation of time and place, and that has to be one of the most live places to make a work that is fragile and intimate. The challenge is to bring an arresting intimacy into public space, and to make it feel like something you've never seen before. What keeps me very interested in the aesthetics of public art is that creation of a surprisingly intimate and fragile experience in time, and how a public work can be a marker for a location, and create a kind of community around it.

I do think that the re-entry to the world after the pandemic will be very profound in terms of people's attachment to being able to meet a friend in person, being able to take a flight, having chance experiences, and experiencing material things. The volume of that shift will be dramatic with the freedom to move, to explore, and the freedom that comes with a sense of a functioning structure of stability and security. I think it will be a kind of revelation in that experience that will be very profound, and because we are experiencing this at a global level, we will all be experiencing it.

An interesting anecdote about the transition from the virtual to the real is when I was in grad school in the nineties, I went to a lecture by Jaron Lanier, who was one of the early inventors of VR, and at that time there was a huge backlash to its development. Lanier talked about his very first experience using VR, after having developed the technology for years. When he put the headset on, he had this unbelievable experience, but the thing he said he remembered the most about it was not the VR, it was this moment of transition, this moment when he took the headset off and he was looking down at the rug of his studio. He had always thought it was grey, and for the first time he saw the studio rug was made up of all these flecks of red, orange, green, and blue, that kind of melded from afar into a grey tone, and he had never understood how vivid the colour of real life was, until that moment. It's a very beautiful story about that transition, and perhaps people's senses will be heightened. To heighten the senses is the medium of any creative work.

TMI wanted to ask you about the globalism at play in your work, in its dealing of information in the digital age. To what capacity do you perhaps see your practice as an antidote to nationalist thinking and the closing of borders that has spiked over the past few years, in relation to what you were saying about public art, and creating communities for people through material things?

SSI love that question because I think being an artist in many ways is a political act, whatever your politics are. Without it being explicit in subject, I'm always focused on it being political in form; in the breaking of boundaries. Any time you reach one location in the work—whether it's in painting or sculpture—you are forced as a viewer to constantly reconsider what you have just seen, and you travel through levels of information that inform each other within that information, in a kind of confusion of hierarchy and a questioning of gravitas.

I hope to have a questioning of the medium itself in an artwork—one that reflects the the complexity and fragility of the experience of being in the world, and forms my philosophical basis for how an artwork is made: to be in constant debate, to try and understand how an argument is made, what is factually true, and how a fact morphs and changes over time. I think that an artwork is this unbelievable medium that does not have to be shackled or limited by the shortcomings of language. Whereas a word can be interpreted in a very hard way, the ambiguity of colour, an experience, or a note in music allows for a complexity in a way that language—while it can be used in the context of poetry, for example—often isn't. Art allows for an experience that encourages questioning, and that spills out into daily life with a subtlety and complexity that mirrors the way information seeps into the world.

TMI understand from your 2012 New Yorker feature with Andrea K Scott, that during your exhibition at Asia Society in 2011, visitors felt compelled to participate in the work by leaving behind small objects, like bus tickets and lunch receipts. How much does the participatory dimension inform your creative process?

SSAny time you move an artwork from the studio to the public realm, it's an experiment. As an artist, you don't know how people will react, no matter the context, and that transition is very interesting. Exhibitions are live experiments that can be thought of as laboratories for human behaviour around an object or an image. What I think is really interesting is that across the board, people's reactions to my work have been to move slowly; they behave differently. If anything, they don't take from the work, they add to it, and that's really from a 20-year experiment of putting extremely fragile works in major spaces, like the stairwell of SFMoMA and the American Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale. At the Venice Biennale, the pavilion was packed with very, very fragile work and five thousand people moved through it a day, and there were no problems with it over that time.

What the digital does in many ways, ultimately, is it creates a kind of longing. There's longing and desire, and those are real emotions.

Part of the participatory dimension of the work is being able to imagine how the work was made, and how it will live after that moment. That's always been interesting to me; that the experience of the work is live, and that you have this fragile moment in your relationship to that work, and part of realising that you're in a fragile moment is that quick wondering of, 'How did it get here?' 'How was it made?' 'What will happen to it?' And then, 'Here I am.' That heightening of a moment is different in the digital. What the digital does in many ways, ultimately, is it creates a kind of longing. There's longing and desire, and those are real emotions. That may be what the digital expresses best, which has complicated implications for both its strengths and its weaknesses as it ever grows as a medium.

I started making work in the nineties, and one of the things I've always done since then is I've always photographed my own work. I've always been really against installation photography, where you see poorly lit rooms with track lights; I'm much more interested in giving the viewer an experience that photography can give, which is a desire for more, because it has edge—it's all about how much you frame. There is longing and desire, and perhaps with that, a kind of grief or excitement, because your emotion is lit, but never fulfilled. That is very much how the web operates: around a creation of mystery and desire that is rarely fulfilled.

TMIn 2010, you presented a work titled The Guggenheim as Ruin as part of the exhibition Contemplating the Void: Interventions in the Guggenheim Museum. The title of that work makes me think about Robert Smithson's 'inverse meanings'—sets of contradictions that are in line with his thinking around entropy, such as margin and centre, or centre and circumference, order begetting disorder, and ruins built in reverse, which is particularly relevant to the title of your work, Guggenheim as Ruin. Would you consider the concept of a 'ruin in reverse' as fitting to your overall practice?

SSThat was an important work for me actually, and I don't know how well known it is. I had been doing a lot of printing and collage, mostly as gifts to museums for fundraising, so it didn't have any purpose other than being a gift, although in some ways the intimacy and a lot of the themes in my work are present in it.

A painting or sculpture can remind you of the new and old spaces that you are leaving, at all moments.

This idea of a ruin in reverse has always been really central to me. There was a piece I did for the first Berlin Biennale called Second Means of Egress (1998), and it was made in the studio of Albert Speer, who was Hitler's architect. I did a lot of research at the time on Speer, and one of the things that was part of the grotesque insanity and in the implicit evil of everything that they were planning was the design for a new capital, Germania, and they started with the idea of what it would look like as an architectural ruin. They studied Pompeii and Rome, because they knew that some day it would be a ruin, and they wanted it to be the most beautiful ruin in the world. For Speer it was a megalomaniac notion of an idea being taken to its hideous destructive end, but also that fragility of knowing that anything made holds the potential to become a ruin.

The work I built in Speers' studio followed an organic crack in the wall that travelled from floor to ceiling and had occurred after the bombing of Berlin during World War II. To take it away from that loaded context, and back to Robert Smithson, Smithson always used the faultlines, the ruptures, and the voids as materials. Part of his idea of ruins in reverse and of order begetting disorder is part of the structural discomfort that I am interested in revealing. I've always thought of my works as landscapes. But not as depictions of what they look like, rather experiments in how they behave. Part of what's interesting about this idea, that all new construction eventually becomes ruins, is how you can breathe life into a moment of experience: we define things in time through it's having an end. To have that end always be a part of the conversation is a way of making the value of life and the question of what it is to be human highlighted as an experience. This idea of a ruin in reverse is threaded through all of my works, and that fragility is part of creating a live experience and the instability that is built into my work.

TMIt is a dizzying experience to imagine all of your projects. When I was researching your work, I found myself entering a headspace where all your projects were sort of colliding and coming into play with one another. I wondered if you've ever imagined your works existing in one infinite realm, or does each work very much exist in and of itself?

SSThis idea of how something generates one thing to the next has always been a fascination. That's why really full catalogues are incredible, because as an artist you can observe how in any artwork, there are a multitude of directions into the next work. It kind of relates to this filmic idea that it's not the endpoint, it's the decisions in between—it's the step in between that creates this movement or flow in an overall body of work. There's this idea that some artists have these bodies of work that jump all over the place, but I think actually they don't; I think they're all generative, and that one work generates the next. For me, it's interesting to make that a subject of the work—that you see a body of work in its generations of itself, and that's very much something I've been doing more and more in the work, as in the show at Gagosian in Paris. There's actually one series there that's really about taking one image, and having that image generate the next, and to play with this idea that an image can grow, accumulate, and appear; but also disintegrate, ruin, and fall apart, and there's beauty in both of those directions.

TMI wanted to continue on that idea of the boundary, which is artfully navigated in your works and provides them with extraordinary tension, so that they seem just on the cusp of a tipping point but are meticulously organised to avoid that happening. This was very explicitly demonstrated in your work, Triple Point (Pendulum) (2013) at the 55th Venice Biennale, which incorporated the pendulum to delineate that boundary. What other strategies of boundary-making do you incorporate in your work?

SSIt's always a question that I want to have brought up, no matter the medium, in relation to the edge and the boundaries we are creating in how we participate in the work. One of the things with the pendulum is that it is a work that makes itself. When you install the pendulum, you use it to measure out how the piece will be made, and as a viewer, you know that. Even with the paintings, there is this idea of showing you what you might not be able to see in life, or what the experience would be, so that you can set that anticipation. As you move closer, for example, there's a kind of tipping point of thinking you've seen an image in a certain way, and yet you're seeing it in another way. A drip of paint, for example, might actually be a photograph of a drip of paint, and something you think is a photograph is actually paint, and something you think is paper is actually acrylic, and your movement towards those elements involves crossing those boundaries of experiencing what an image or what a sculpture is, and flipping between the two.

The paintings at Gagosian are three panels of a different depth, and you don't understand that unless you move around them, and then you see the image fall apart as a plane. In any piece, the boundaries are highlighted, as in LaGuardia, where the piece will go through the floor, so even the architecture's boundaries are highlighted—you're standing in departures, but right below you there is a flow of humanity arriving as you leave. A painting or sculpture can remind you of the new and old spaces that you are leaving, at all moments.

TMElizabeth A. T. Smith has referred to your intelligent design as a marriage of 'rational conception' and 'intuitive execution'. With the immense scale of many of your works, I wondered if 'impossible conception' has also been a feature of your design?

SSOf course, it's a very central idea to architecture and urban planning. I don't know what the exact percentage is, but for sure over 50 percent of an architect's projects are never realised. This idea of modelling, conceptualising, imagining, and even this idea of imagining the past from the future and the future from the past through a visual means—whether that's a modelling or a drawing of that information—is definitely in the work.

In an architect's bodies of works, it's not just the building, it's the trove of ideas that didn't happen, but they in and of themselves are works of art. That idea of, exactly as you said, the impossible, or the potential of those things that can only be imagined and not achieved, is what you want to do as an artist. It's a dimension of time that you want to be thrown into, and it's the potential of an artwork: to put you into that world of imagination. In the midst of this crisis, I think the idea of re-imagination is especially relevant.—[O]