Sawangwongse Yawnghwe's Historical Minimalism

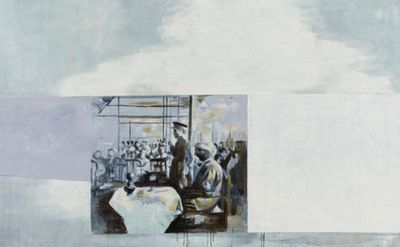

Sawangwongse Yawnghwe. Courtesy: the artist.

Sawangwongse Yawnghwe. Courtesy: the artist.

A direct descendant of the royal family of the Shan State in Myanmar, Sawangwongse Yawnghwe knows history and archives do not always tell the whole story.

Working across painting and installation, Yawnghwe examines patterns of political abuse, military repression, and the inadequate treatment of ethnic minorities in Myanmar by introducing new perspectives to make sense of social and personal relations.

Born in the Shan State of Myanmar, Yawnghwe is no stranger to political unrest. Yawnghwe's grandfather Sao Shwe Thaik was the first president of the Union of Burma following the country's independence from British rule in 1948.

Sao Shwe Thaik died in prison after the 1962 military coup carried out by General Ne Win. Yawnghwe's family was driven into exile in 1972, escaping first to Thailand, then to Canada, where Yawnghwe was raised. The artist has been trying to make sense of Myanmar's political developments since.

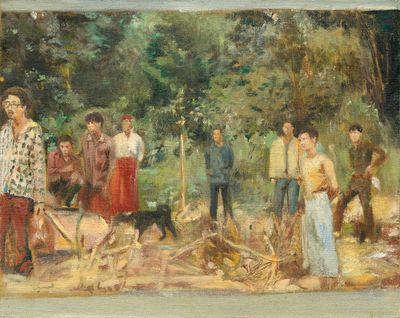

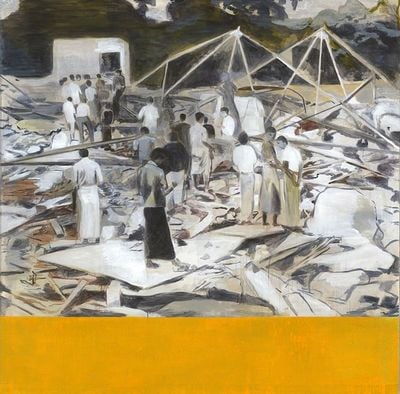

Early works show realistic portraiture alongside personal histories that resonate more broadly with Burmese society. In Their Newfound Freedom II (2005), a cluster of citizens are gathered mid-jungle, alluding to the SSA army camp where the artist was born.

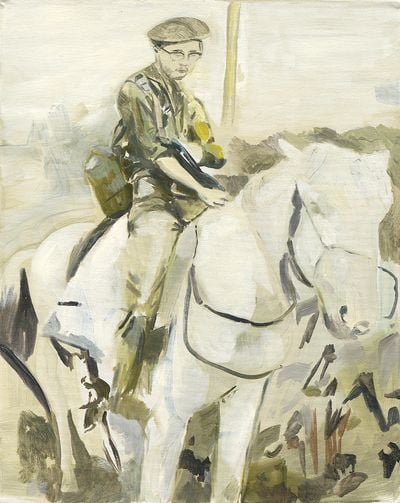

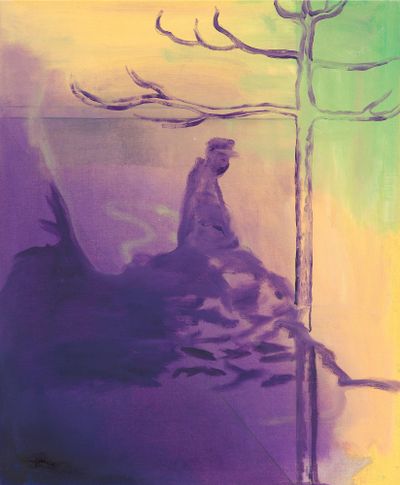

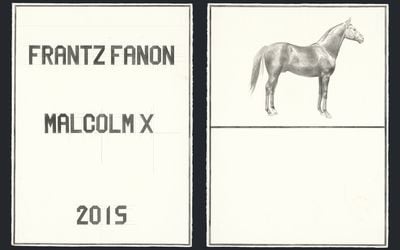

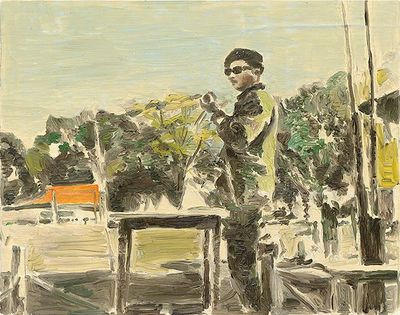

Yawnghwe's father returns across the artist's paintings, often rendered with a gentle expression as in My Father (2005), showing the patriarch riding a horse, wearing dark shades and a military uniform. Yawnghwe's grandfather, on the other hand, fades into memory—rendered as a faceless outline in oil on linen, on a parchment-like backdrop in My Grandfather (2004).

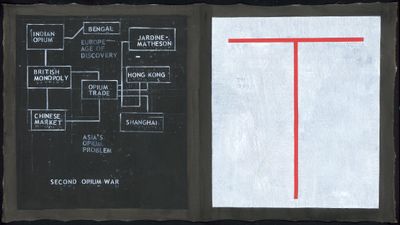

Yawnghwe's paintings evolved to blend figuration with abstraction, showing bright squares painted in a range of colours besides otherwise realistic portraits and landscapes.

Colour operates symbolically across canvases like affective notes, often rendering historical events against abstract colour grids to structure paintings and generate a sense of order.

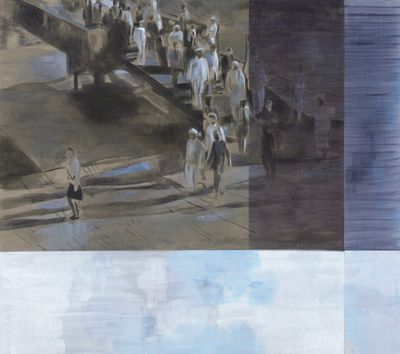

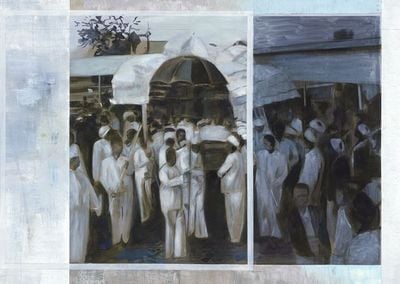

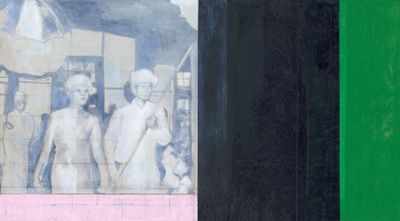

In My Father (Black) (2019), the portrait of the artist's father takes up less than a third of the linen canvas, with the remaining space submerged in black oil paint, while Midnight 1947 (2019), referring to the dawn of the general election for Myanmar's independence, shows a crowd from afar framed by lilac and white tiles, with glimmers of colour entering the grey-toned scene.

As with the artist's paintings, his installations reference the political climate of Myanmar, drawing from current events, family archives, and Burmese history with an emphasis on the Shan minority (to which the artist belongs), which is represented by only ten percent of the country's population.

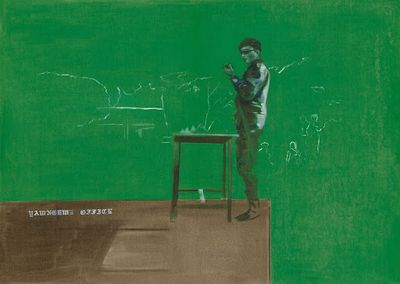

Recovering concealed histories, Yawnghwe Office of Exile at TKG+ in Taipei (11 May–7 July 2019) was formed as a 'State Museum' narrating stories of exile and ethnic cleansing, otherwise censored in Myanmar, where the military rules under the name of democracy.

Narratives presented as 'fiction' are partially abstracted across a series of paintings depicting men in military uniforms against bright red and green backdrops.

Partial truths and memory are reorganised in Yawnghwe's new series of paintings, made in response to the Myanmar military coup in February 2021, when a military government in Myanmar seized power, declaring the outcomes from democratic elections in November 2020 fraudulent.

The protests that culminated in over 900 deaths and 5,000 arrests served as the starting point for Cappuccino in Exile, the artist's solo exhibition at Jane Lombard Gallery in New York (10 September–30 October 2021).

Arranged in geometric grids following the golden ratio, paintings are organised into ordered segments, providing the foundation for a process that is mostly intuitive.

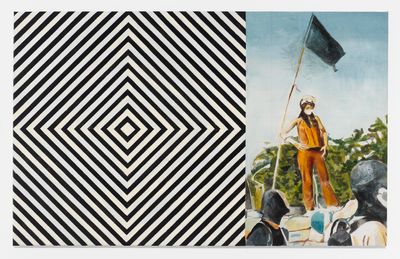

Resulting works like Bill Young and Protest III (both 2021) set geometrical patterns aside portraits of figures associated with Burmese politics and revolution, amongst which Bill Young, commanding officer of the C.I.A, and a masked female protestor evoking collective dissent.

In the first monochrome painting, the officer is shown as a faceless young man across one third of the canvas. On his right, a large diamond-like shape is rendered against a black backdrop alluding to the sinister occupation of the missionary's son turned hitman.

The same distribution between pattern and figure can be found in Protest III (2021) where a monochrome grid occupying two thirds of the canvas precedes the young woman leaning against a black flag.

Paintings like Louisa Benson with rifle (2021), showing the former model turned revolutionary—this time, across the larger section of the canvas—address the immediacy of revolution and the new faces that may lead it.

In My Grandmother/Shan State War Council (2019), for instance, rectangles of red, black, and blue—recalling the old flag of Myanmar—surround a female figure wearing black shades and rendered in grey tones.

The artist's propensity towards serialisation generates narratives weaving past and present across patterns, figures, and shades. Amongst recurring figures is Burmese politician and revolutionary Aung San, first sighted in Aung San in Palong (2019), overlooking the signing of Burmese Independence.

At Jane Lombard Gallery, the politician is shown on his deathbed, with his body tucked away in the lower right-hand corner of the canvas in The Funeral of Aung San (2021), stripped of its commandeering authority.

The following transcript, edited from a conversation that took place on the occasion of Cappuccino in Exile, is being released ahead of the Kathmandu Triennale (11 February–11 March 2022), in which Yawnghwe is participating, with a focus on cultural narratives from communities that have undergone internal colonisation.

KWCould you tell us more about how the work that composes Cappuccino in Exile came about? What kind of materials did you use? Why did you choose to place the arch of garments hung along a clothesline at the entrance of the show?

SYIt relates to the Spring Revolution in Myanmar in February 2021, when clotheslines were hung up in the streets to prevent police and military from passing through.

In Myanmar, there's a belief that men shouldn't walk under women's garments because they could lose their power. The arch is a gesture showing that the protest continues in the gallery space.

I got the silk pieces from a collector who had them since the late 1970s and 80s. They are all antique pieces that have been titled 'Yawnghwe Office in Exile', based on the exhibition of the same name that was hosted by TKG+ in 2019, and are editioned and numbered. They are readymades, in a way.

KWCould you say more about the patterns? As far as I know, some are replicated on the paintings as well.

SYYes. I work the patterns into the paintings alongside photographs that are either drawn from historical archives or recent images from social media, including Facebook posts showing protestors across Myanmar. This show includes both contemporary images and historical images.

The patterns have changed the way I look at the paintings. They bring me to a place of unknowing, adding a degree of uncertainty as with the political situation in Myanmar.

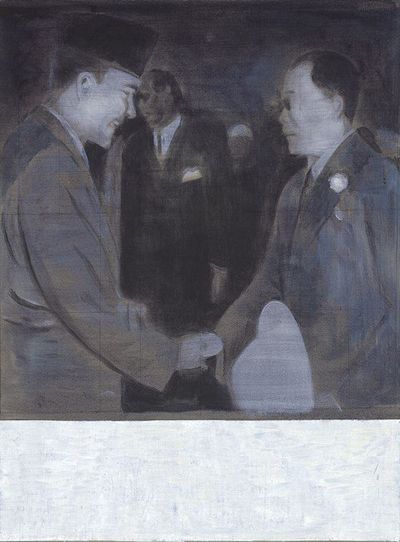

KWCould you tell us more about Aung San, Atlee and U saw in London (2021)? Which meeting does this represent?

SYIn the middle, we have Aung San, the leader of the independence movement in Burma in the 1940s. Former British Prime Minister Clement Attlee is depicted to the left, and Burmese politician U Saw is the man in sunglasses immediately behind Aung San.

The original photograph was taken in London, I think, when Aung San went to England to negotiate the Independence. He was later assassinated. U Saw was arrested and hung for it. It's a mystery who killed Aung San. There's a document that claims the British orchestrated the assassination.

KWAung San was also the leader of the Burmans, right? The ethnic group.

SYDuring the war in 1943, Aung San was a part of this group of 30 comrades who joined the Japanese. His troops came from the Thai prisons found evading British Burma. They invaded Thailand together, going all the way to Northern Thailand where they committed a lot of atrocities.

Churchill wanted to trial Aung San for his crimes, but the history is complex. One minute Aung San is working with the fascists, the next he becomes the George Washington of Burma. I explore these complexities across the visual elements in my work. It's a recurring theme linked to family archives and history.

KWIs your family related to Aung San?

SYNo, but there's a lot of photographic documentation of my grandfather and Aung San together. I believe Aung San stayed at my grandfather's place in Yawnghwe. I think Aung San was a very good politician.

The Panglong Agreement (1947), which brought all these ethnicities together to form the Burmese Union, was an attempt to look towards federalism. That would have been ideal. Unfortunately, Aung San was killed the same year.

KWIf I remember correctly, Aung San was also the father of Aung San Suu Ki.

SYYes. In this sense, the image also relates back to the current political situation in Myanmar.

KWCould you talk more about the pattern that makes up at least one to two thirds of the composition of these paintings? Why did you decide to combine this pattern with the work?

SYPrior to the pattern, the painting was monochrome. For TKG+, the monochrome paintings were made from a single colour and image. Red, white, and blue were selected to raise association with local tribes, as they are the commonly used colours, because indigo is easily accessible. The red oxide rust.

Patterns and colours on the painting form an image, but they are also set besides a photograph resulting in a new composition.

I feel like the juxtaposition of bold colours with the photographs is very violent. It reflects what I want to say. It's always fascinating to see what happens to the surface of the painting, and how it reads. It moves beyond an image.

KWWhat do you mean when you say it moves beyond an image? Does it have a conceptual basis too?

SYYes, I suppose. Obviously, it's easier for me to read into the image, but the patterns have changed the way I look at the paintings. They bring me to a place of unknowing, adding a degree of uncertainty as with the political situation in Myanmar.

It would be a fool's errand to pretend to understand what's going on there. In reality, no one knows what is happening.

KWIt's interesting—I think about the figurative parts of your work as returning memories. The way they are painted makes them look like ghosts haunting the present. They almost resemble Polaroids, or an aesthetic that reminds me of something from the past.

Should we walk to the next painting? Which one is that?

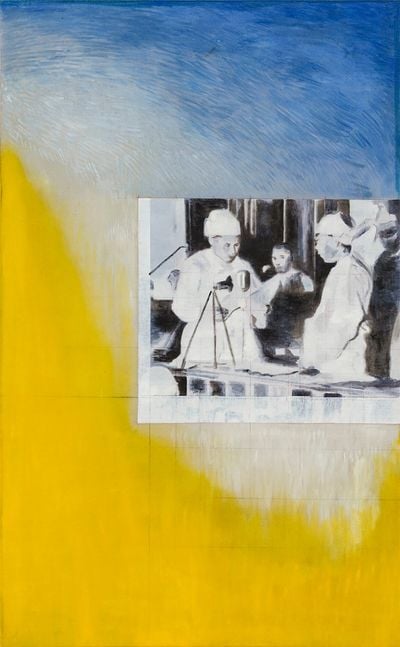

SYThis would be Aung San in China meeting with the Japanese military Aung San, April 1941, Hainan Island, China (to receive military training by the Japanese Army (2021). This was in the 1940s, when he was thinking about collaborating with the fascist military once more to liberate Burma.

They succeeded, but they had to leave. When the Japanese lost the war, Aung San quickly switched sides to align with the Allies.

KWIt's an interesting history. Aung San had this connection and this belief in Pan-Asianism, until the end of World War II. The whole idea of a united Asia under Japanese leadership came to an abrupt end. Aung San seems to be a running theme in this exhibition.

As far as I can remember, there is another painting showing Aung San's funeral. This one is called The Death of a Revolution (2021).

SYAung San was a symbol of the 1988 protest, so he comes up a lot. When I make something, I tend to make a series out of it.

The painting references Aung San joining the Communist Party. The red and black planes refer to the fascist colours. These associations are processed through the act of painting, and this is what emerges. There's always an element of surprise in each work.

KWWhat I found interesting about this one was that you titled it The Death of a Revolution and it is dated to 2021. It does not say exactly which revolution.

Of course, we know what kind of revolution it might be because the person in the picture is Aung San, but could you say more about the kind of revolution you had in mind when you titled the painting?

SYThe title came from a friend to whom I had sent the image. When he said, 'The death of a revolution', he was referring to the political struggles in Myanmar since the coup and the general reaction to the event from local and international communities.

Of course, it's still unfolding, but there had been a lot of military brutality. Protestors had to run away or risk being jailed, tortured, and killed. The painting referenced these events and Aung San became a symbol for the 1988 protests.

KWThere have been so many revolutions in the region that is now Myanmar. Perhaps you thought it unnecessary to specify the revolution in your painting.

SYYes.

KWThe woman wearing a face mask featured in Protest III (2021) is a contemporary protestor, whose image came from Facebook, right? Did you know her personally?

SYNo. The image was captured during the nationwide protests on 22 February 2021. There were many women acting in defiance to the military. It was very encouraging for us to see. Under military rule, it represented a new modernisation of ideas and attitudes. The black flag was very fitting—it's almost like a void that carries a foreboding feeling, as if something bad was going to happen.

KWIs the black flag also from the Facebook image?

SYIt is. It was in the image.

KWThis painting has a similar ratio to other paintings.

SYYes. It's called the golden ratio. If you take the height divided by the width, you get 1.6. The formula follows the Fibonacci sequence. I have a fascination with this type of division at this size.

It has to be this ratio specifically, so you get a square and another one that's a little bit more than half on top. It's a visual tool but also like a game for me. It gives me a solid structure so that I can have freedom within the limitations.

I really like how both images get interrupted by each other but remain a single image.

KWDo you do this for all your exhibitions? You create a common denominator for the paintings in the show and for this one, it's the golden ratio?

SYNo, I've been using the golden ratio for some years now. It's become a kind of obsession. I find this cut very visually pleasing and so I get a kick out of it. I enjoy the fact that the two images have nothing to do with each other yet sit on a single surface.

KWIs that how you bring the two elements together? The figurative and the abstract?

SYYes. Usually there's a big risk involved. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't. There were others you don't see here that were failures. I had to do a lot to arrive here.

KWIf you look at the figurative parts, it's like a visual memory that is recognisable. On the other hand, there are abstract parts that remind me of the gaps in memory and in history that cannot be explained and are not accounted for.

I find the opposition between the abstract and the figurative very interesting, but I don't know if that's something you've been thinking about.

SYYes. Each section is polluted with the other, and that's what makes it work. I've tried to replicate the pattern by itself. It looks really boring somehow. For me, it doesn't work.

There are many patterns, but they function just like one. It could be a single colour by itself, like red or blue, and it would work just as well as an element in the painting.

But in the end, it's something I have to work through to find out what comes after. The difficult part is always going to be what comes after.

KWI think we are back where we started when I quoted Sawang saying, 'It is a single-minded effort to bring discernible order to complex political situations'.

Your life and work as an artist is connected to these complex political situations and you try to bring order to this thinking about Myanmar right now, but also in the past and how it connects back to your life.

You said each section is polluted with the other, but still, I see that you are drawing lines and these lines are certainly very personal. These visual stories are written in your handwriting.

SYYes. The question that remains constant is this idea of the lack of roots and what you make of it. For instance, do I go back to find my roots? What does the lack of it mean? It's a recurring theme.

On the other hand, it's just like a painting made with tape or with a spatula. Two different things, but when it works it becomes one. And for me, that signifies freedom.

KWCould you tell us a bit more about the process of making the images? Do you plan before you paint?

SYI usually start with a grid to transfer the image. It provides a good structure and I go in with the brush right away. There's no drawing. When the photographic image is almost finished, I start thinking about the left side. The abstract pattern. Sometimes it works out and it's good, sometimes it doesn't.

So everything comes down to the pattern. I don't have anything planned—everything is decided during the process of painting. I figure things out along the way. Maybe I have a good idea and then I try it. If it works, it works. If it doesn't, it gets covered up again.

KWIn Western art history, in the history of modern art especially, grids are important as they offer frames to think through. I was wondering if you were using the grids to incorporate the historical themes from your work in contemporary art—if it was maybe an attempt to bring more Asian or Burmese history into the history of art.

I know you are very interested in historical paintings—an interest you developed during your time in Italy following your studies in Canada.

SYOf course, painting itself is a language, one that I belong to. Giotto, the Italian painter, was my earliest influence. He made the greatest impression on me during my time in Italy. I fell in love with painting ever since.

When I immigrated to Canada at the age of 12, I saw on the news that Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers (1888) sold for ten million dollars in Japan, which was eye opening. I remember thinking, wow. Being an artist is a real job in the West.

KWWould you agree that one of your intentions is to bring Burmese history into the history of art as well, and give it a place there?

SYOf course. In this case, it would be the history of the Shan minority and the ethnic struggle in Myanmar against military rule.

KWI wanted to go to the Bill Young paintings, because Bill Young is another recurring subject in your work.

SYBill Young was the son of a British missionary. He grew up in Burma, learning different local languages, and lived with the tribespeople.

KWIn the late 1950s, Young started working for the C.I.A. He became involved in anticommunist activities in the region later on. Was Young a friend of your father's?

SYThey were not. They were probably working together. According to the stories, Bill Young and my father came up with the name for an army. The Lao army, or something of the sort. I'm not sure of the name.

While the C.I.A. is not some secret no one knows about, these are all personal stories in many ways. The stories are all told by my father. I can't know for sure if they are true. Bill Young ended up telling his story to someone in Hollywood. The story is on the shelf somewhere.

KWThere is another person who also appears in the exhibition twice: Louisa Benson. Before joining the rebel army, she was a beauty queen. From her dress in one Louisa Benson II (2021), she looks like she is from the 1950s, and she appears again is in a swimsuit. I guess that was from her beauty queen days.

Then in another painting, Louisa Benson With Rifle (2021), she is dressed as a rebel. When was that? In the 1960s?

SYI think it was around 1964. She was married to a commander of a Karen National Union troop who led the fifth brigade. He led them into the jungle and was assassinated. I knew Louisa personally. She would often visit my father when he was ill. So again, this is almost a part of the family archive, drawn from people I know who are related to the family.

Of course, this exhibition, in light of the coup d'état, is focused on symbols and signs of protest and dissent. It is also a reaction to what happened in Myanmar during the coup in February 2021.

KWI like that in this exhibition, you emphasise the role of women in the struggle as well. Your aunt and your grandmother appear in previous exhibitions, but it's always good to see images of female fighters. They remain rare, especially in historical contexts.

SYThe pattern in Protest V (2021) is from the Shan flag, which is the flag of my ethnicity. I wanted to make a monumental painting about it, because it represents protest and I wanted something that gave it importance, hence the red and blue patterns.

KWDo you know where the picture was taken? Under a bridge, perhaps?

SYI think either in Tao Chi or in Yangon. It looks like Yangon.

KWYou said you were drawn to the Shan flag in the painting Protest V (2021), but you did not draw it on the patterns besides the image inspired by the sarong in Protest V?

What is the reasoning behind this? Or was it an intuitive decision?

SYIt was a painting decision. I didn't want the same colour to come up again. I needed two opposing images to achieve the effect—it's like a distinct cut of an image.

KWI find it so interesting to see the order in this exhibition and on the canvas, because your studio is always filled with oil paints, tubes, pencils everywhere—it's one big chaos, though probably not for you as you know where everything is! It's good to see the paintings spread out in this space.

SYThe worst place to look at painting is my studio. The magic for me is when it goes on the wall—that is the moment I also get to enjoy. This is why we need exhibitions. Otherwise, the painting is not complete.—[O]