Sim Chi Yin and Maaza Mengiste: Intervening in Colonial Archives

In Partnership With Zilberman

Left to right: Sim Chi Yin. Photo: Joel Low; Maaza Mengiste. Photo: Nina Subin.

Left to right: Sim Chi Yin. Photo: Joel Low; Maaza Mengiste. Photo: Nina Subin.

Singaporean artist Sim Chi Yin has developed a research-based practice that excavates historical moments, looking at the continuing effects of the past on the present.

Based in Berlin, where she is represented by Zilberman alongside Hong Kong's Hanart TZ Gallery, Sim works across film, photography, and text-based performance to document far-reaching topics.

These have ranged from the depletion of sand as a resource, the subjugation of Chinese workers to 'black lung disease' as a result of dust from mines, or migrants in Beijing referred to as the 'rat tribe', living in windowless housing beneath the ground.

In 2017, Sim was commissioned as the Nobel Peace Prize photographer to delve into the work of that year's winner, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. The resulting commission, Fallout, was presented at the Nobel Peace Centre in Oslo (12 December 2017–25 November 2018).

That project led Sim to the North Korea-China border and the United States, where she photographed landscapes related to nuclear events and activities. Pairing images from each nation side-by-side, the eerie photographs relay the silent threat of nuclear activity.

A video installation of the diptychs, titled Most people were silent (2017), was shortlisted for the Aesthetica Art Prize in 2019, having been included in an exhibition of the same title at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Singapore a year prior (21 July–10 October 2018).

Two works from the series are also now on view in the group show Devour the Land: War and American Landscape Photography since 1970 at the Harvard Art Museums (17 September 2021–16 January 2022).

For the past decade, Sim has also been investigating the 12-year anti-colonial war in British Malaya, which was termed an 'emergency' by British colonial powers. The work traces the path of her paternal grandfather, a journalist and left-wing intellectual who was deported by British Special Branch officers to southern China before joining the Chinese Communist Party guerrilla army unit, and remains a taboo topic in Sim's family.

Through her grandfather's life, Sim reflects on the ghosts of British Malaya's anti-colonial war—Britain's longest overseas conflict following the Second World War—drawing images from the colonial archive at the Imperial War Museum in London, which she photographed on a light table to reveal markings on their backs before exhibiting them as glass plates.

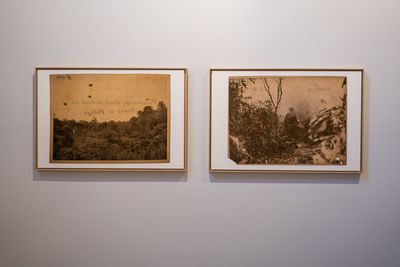

Titled 'Interventions', the images were presented for the first time at Les Rencontres d'Arles (4 July–26 September 2021) in an installation curated by Sam I-shan, previously curator at National Gallery Singapore, Singapore Art Museum, and Esplanade Visual Arts, before being shown at Zilberman in Berlin (One Day We'll Understand,14 October–27 November 2021) in a new curation by Lotte Laub.

The exhibition included the artist's 'Remnants' (2017–ongoing)—eerie photographs of conflict sites of memory across Thailand and Malaysia—as well as a video installation capturing former deportees and exiles performing revolutionary songs.

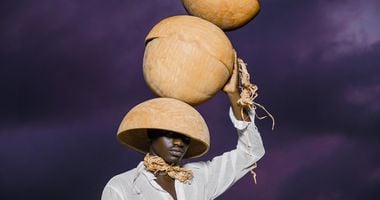

On the occasion of the exhibition, Sim invited writer Maaza Mengiste to discuss intersections in their works, in particular Mengiste's book The Shadow King (2019), set in the second Italo-Ethipian war of the 1930s. This edited transcript of their conversation will also be included in an upcoming catalogue published by Zilberman.

MMQ Placeholder

SCYThank you so much, Maaza, for joining me at the opening of my first solo exhibition in Berlin. This work is very close to my heart, and I have been working on it for almost nine years, so it's really meaningful to discuss this with you, as there are so many overlaps in our work.

To begin the talk, I will first recite a letter to my grandfather, and then we'll use extracts from Maaza's book The Shadow King (2019) as jumping-off points to talk about some of the themes we share in our work.

Dear Granddad,

I never met you and the family, from the time I was a child, never talked about you. Except once. Dad mentioned in passing that you had died in China in the 1940s and, for some reason, had a monument built to you.

I thought it was strange that you—having been born in Hong Kong but then taken as a baby to Malaya, where you grew up, lived, and worked—would have died in our ancestral village in China. Your father had left the village at the turn of the 20th century, along with a wave of migrant Chinese labourers headed for Southeast Asia, America, Australia, and Africa.

And why did the family never talk about you in the 60 years since your death? Why does Grandma's gravestone not bear your name?

One Chinese New Year, on my visit home, my mum handed me a black and white photograph. The man in the photograph stood confidently, hands on hips. He was not tall, had a high forehead and thick lips... and a camera was slung around his neck. Another photographer in the family? I was intrigued.

I've driven around northern Malaysia and southern Thailand, in the towns where you'd lived and worked, in the so-called 'black areas' where the Communists were active. Where they had ambushed Commonwealth soldiers, shot British rubber estate managers, where they hid in limestone caves, lived with tigers and elephants in the jungles. I visited old tin mines founded by the British, and that jail where they had kept you...

I went to the cemeteries of Commonwealth soldiers who were killed by 'bandits' and 'communist terrorists'. One of their graves reads 'One Day We'll Understand'.1

MM'It is the land that carries our suffering when we die. It is the land that remains the same, no matter what we call ourselves... only soil will remember who we are, nothing but earth is strong enough to withstand the burden of memory.'2

When I first walked through this exhibit, I was reminded of this passage, which is from my novel The Shadow King. I was particularly struck by the photograph that opens the show, of an elephant in a dark forest at night.

Chi Yin, could you explain what is in the image and what that represents to you?

SCYThis project, which is titled One Day We'll Understand, is made up of three main parts. One part is called 'Remnants', another part is called 'Requiem', and the last part is called 'Interventions'.

We chose to begin this particular installation with 'Remnants', and specifically the series of landscape pictures I took around northern Malaysia and southern Thailand, revisiting what I call 'informal sites of memory' from this conflict. They're informal because this war has never been officially memorialised.

I came upon these sites through research into places where something happened in this war, like an ambush or gunfire fight, or a particular cave that the communists were known to have hidden in before taking a strike against the British.

This series of landscape pictures work with this idea of the land as an unspoken archive of a war that was never declared a war. The British extracted a lot of rubber and tin from Malaya, which was an important colony for them post-World War II, especially when rubber prices were high.

This series of landscape pictures work with this idea of the land as an unspoken archive of a war that was never declared a war.

For insurance purposes, they could never call this war a war, and they always said it was an 'emergency'. So with these landscapes, I sought out traces of this past that has never been officially memorialised.

The elephant picture was taken in the jungle that was the base of the leftists' army. That encounter was quite magical, because it was my first night in this jungle. I had gone to look at what I was going to photograph from the next morning onwards, and on my drive back on the highway, which now segments the habitat of the original habitat of these elephants, I saw a family of elephants and took several pictures.

In this frame, the baby elephant has locked eyes with me. I shot many frames that were perfectly sharp, but in this particular frame I moved, I think maybe out of fear, or the baby elephant moved as well, so it created this blur. Once I shot the picture, I knew there was something special about it.

There was something in this land that humans did not want to remember, or humans don't articulate anymore, but there's something about how the non-human actually remembers. And of course, we know all about elephants and memory. And so there was something about this encounter in this picture for me that opened up this quest to try and photograph traces of this conflict in the land, because the land has a memory.

MMOne of the things that I noticed immediately from that photograph is the blur, and it's also a night shot, so it's full of shadow and you cannot see things clearly.

I don't know if there is a better metaphor to represent what it is like to look back in history, maybe your own family history, when the only documentation you might be able to find are those that have been created by colonial powers. Trying to find intimate stories from state-approved documents is a blurry project, quite literally.

I wondered about this impulse of colonial powers to document everything that they have done, and your role in trying to intervene in the photographs and documents—could you talk about that process?

SCYMy base medium is photography, so I, too, have an impulse to document. But of course, when we're looking at archival topics, we are really looking at the documents and photographs that were left behind.

Unfortunately, they're predominantly colonial sources, because the 'other side'—usually the losing side—did not have the same kinds of resources to photograph, document, circulate, and preserve their own records.

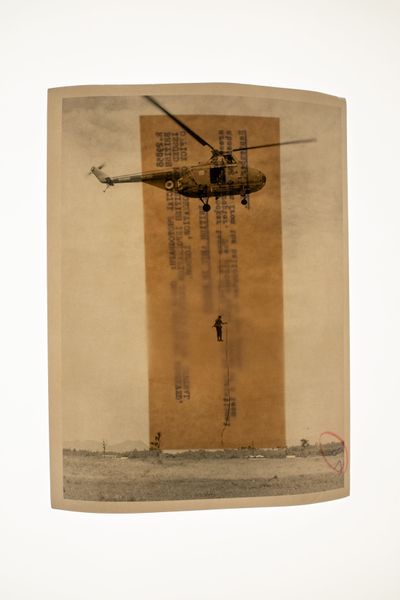

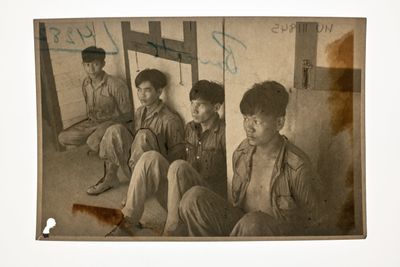

The 'Interventions' series, which are presented on glass, are pictures that I selected from the British colonial archives, primarily the Imperial War Museum archive in the U.K.

I have looked at the representations of this particular war and its combatants. And of course, this being the British military archive, it's predominantly showcasing the triumphant white bodies that smashed this local leftist insurgency.

I reinterpreted those images visually by using a very strong backlight to merge the backs and the fronts of the prints into one plane. In doing that I'm trying to unpack and unveil the layers of indexing and indexicality that go on in the colonial archive.

There are different coloured wax pencil markings on the backs along with punch holes; black outlines that suggest particular images have been circulated to the press for propaganda use, and things like that. That's why I decided to show the prints with verso and recto merged into one plane.

For this show, we printed them on glass instead of regular paper, because I want to work with this idea of legibility and illegibility and transparency; it's a kind of seepage across materiality and time. In printing on glass, I've done these multiple transfers, and we're reverting them into glass negatives.

I'm starting to think about the medium of photography and what it meant in colonial times, to consider the colonial eye, the colonial camera, and the role of the photographer in colonial wars, which is something that you write a lot about in The Shadow King.

MMI think these photographs were never made with the intent of having someone like you or me, decades later, look at them, and I think they're supposed to be looked at straight on. In comparison, the way that you process your works is at a side angle, and you're looking at it from the back. It's a prismatic view, whereas these images were made to be looked at only for their straightforward nature. I think that's what makes this exhibit so powerful.

SCYIf there are no names and no photographs, how do we mourn and how do we remember?

MMI'm going to read a very small section of my novel that is about an Italian colonial officer wanting to document certain scenes, and then I'll just read a very short section of a photograph that was made, but I describe that photograph through words in my novel.

'Go meet my convoy when it arrives. We'll start documenting this new prison from the beginning. We'll record everything. They'll remember what we did to build this empire. He is a body suspended in the mean play of light. A figure deformed by obedient shadows. There he hangs in a beam of dying sun, held up by a tree bowing from his weight. See his head and its bloom of curly hair, the shorn ear that appears like a dip on a narrow jaw.

MMWhat is plain to see: a neck arching horribly, the spine distended, a mother's son pinned against a ripe afternoon sky. Behind him, the valley shrinks from the eager eyes of uniformed men. And what are they, after all, but the other sons of other mothers, and he the glorious proof of their mechanised ambitions?

What we see: a boy pulled into manhood, a soaring body held back by gravitational laws. See him stretch against the terrifying rope, note the legs that kick against the downward tug: behold the rebellious silhouette spinning in a burning sun.

MMAnd there, see him, too, at the edge of the frame, the taker of this photograph, the thief of this moment, there he is, almost out of view, made visible in the shadow stretching toward the elevated feet, a dark figure of a man firmly in focus, the camera pointed toward that defamation.'3

I'd like to talk a bit, Chi Yin, about the work that you do in the archives, that counter-archiving, and something that I work towards: moving against the grain of what we find documented. Could you talk about some of your experiences in the archives and some of the inaccuracies that you've discovered?

SCYAs I alluded to earlier, this is the British military archive and the pictures were taken for two main purposes, one was propaganda and the second was military intelligence. I went in with the hope of finding more representations of the 'enemy', but of course I was to be disappointed.

And where the insurgents appeared, they were always nameless, and they were often in postures and gestures of subjugation.

They were often arrested, or they were being paraded as trophies of some sort, or they were seated on a police station floor looking quite defiant but also tired at the same time. And they were always nameless, while of course on the colonial side the names were quite detailed. Even the dogs had names.

Place names are often mangled. There were place names written in the local languages that were misspelt. I was told that a lot of the place names were deliberately left vague for military intelligence reasons.

Even to find my grandfather's name in the archive was very difficult, and it took about six years, because he has a Chinese name, and of course in the British records it was rendered in English, so it was some kind of Romanised Chinese written in letters.

I had no way of finding his name. I used multiple permutations and I simply couldn't find it. Finally, I used the last photograph that what we have of him; it's his prison photograph and it's very faded and torn. I could really not tell what letters they were but over time, we managed to piece it together and find out. You had a similar process with your uncle, right?

MMI'll tell you the story of my uncle, and as I speak of it, I want all of us to try to imagine how many thousands or millions of lives, of existences, are completely erased simply by spelling errors in museums and in archives.

I was at Oxford University several years ago working on something completely separate from my research, but I knew that, in one of these museums, there was a photographer who had travelled through Ethiopia during the war with Italy and that he had bequeathed his archives to this museum.

I knew that he had passed through a section where my family lived, and that my great uncle had been his guide, protecting this photographer against Italian fire while he was going through this area.

MMMy great uncle's son asked me to look and see if my father's picture was in the archives. So I contacted the museum curators and asked them if I could look at everything that this photographer had taken. They brought out all his negatives and all of these albums and I started going through them. They asked me for my great uncle's name, and I gave it to them, Haile Yesus, and they said, 'There is nothing here with that, but you're more than welcome to look.'

I kept looking, and at some point I'm getting these locations that are very close to my family home. I turn the page and I see a row of men with faces just like mine, and I looked at the name and it was so butchered—it was nothing like my great uncle's name.

I called the curators over and said, 'That's my face.' And then I told them, 'This name is not my great uncle's name, but I can correct it for you, if you'd like.' It also said that the war in Ethiopia, which began in 1935, had begun in 1940, which is also completely incorrect. It's just only when the British got there that the war actually started, according to this photographer.

MMSo they went through and corrected all of this. They were kind enough to give me a copy of a photograph. I took it to my uncle and he told me, 'This is the first photograph I have seen of my father at this age.' In that photograph were my father's older brothers, which is where the striking resemblance came from. I didn't know that they'd all participated in this war.

SCY... I'm trying to unpack and unveil the layers of indexing and indexicality that go on in the colonial archive.

MMSo that's just one story from one album of one photographer of one year. And hearing you speak of your own experience, how many spelling errors could there be in these archives? How many do we have that don't translate so easily to English? And how many family stories have been completely erased or lost, even now, because of something that simple?

MMI was really struck by the care that you have taken in recording your family's stories. That is, I think, the only way, not only that your family story can be known, but if there's anyone else in this room that might have any connection to this history, there is a possibility that you might find a path that leads you to your own family story, which is why these exhibits and conversations are so important.

SCYWhich brings me to one of the things in your book, which is that you try to give names to people. You know, the battalion of women who fought in this war, you name them one by one, even if one is just called 'the cook', but all of them have specific names.

If there are no names and no photographs, how do we mourn and how do we remember? It makes me think about Judith Butler's writing about 9/11 and the hierarchy of bodies worth mourning and grieving.4 How do we grieve if there is no trace of a person?

I've written about the way that disappearances have been used by different regimes, not only as a way to quite literally get rid of a problem if a person is rebelling against the system. It disrupts that process of grief that could bring healing, and then might create more anger and more action, say from the side of the family.

What do you do with the absence of a body when the absence is felt but you still don't have anything to fit into that moment? You have a pocket of space where grief should be, but it's incomplete.

I thought about these stories that have come to me ever since my novel was published. Ethiopians have emailed me, Italians have emailed me, people from different parts of the world who have a connection to this history in one way or another have said to me, 'My relative was disappeared by the Italians. Can you help me locate them somehow?' Or, 'My grandfather was a soldier in the army for Italy. He died but the Italian government wouldn't acknowledge that soldiers were actually killed by Africans.'

And so there was nothing that the family really knew. I've created an online website that features some of the photographs I've been collecting for a number of years from the Italian archives.

I have a page that's called 'Memories without Faces', so that people can share their own family stories with the absence of photographs. This is an online archive that's continuing to grow. I'm getting stories from all over the world. These stories are everywhere, and I think that the overlapping nature of the histories that we're talking about might surprise us.

SCYSometimes the only faces that we have of these people are them as dead people. I've been interested to find post-mortem photography from this particular war. There's this one image, which I'm sure was at some point removed from the official colonial archive because I found it on eBay, and a friend bought it.

That leads to questions of the multiple violences that occur in such wars and subsequently in the circulation of images, in the commodification of some of these images, and where they end up.

This particular image shows a guerrilla fighter who was obviously killed in the jungle and carried out on a wooden stretcher or ladder. He's clearly dead, but he's propped up against a wall and photographed, and I've seen multiple images like this from this conflict alone.

I've become interested in this practice of post-mortem photography. I understand that it probably was for intelligence purposes, but it really opens up questions of the violences that visit these bodies.

MMIt makes me wonder about how you avoid falling into those traps of looking at a colonial photograph. These post-mortem photographs, how do you reinvent that image into something else?

SCYWell, with this particular body of post-mortem photos, I've chosen not to do anything with them so far. I've just shown them very sparingly, usually just one in each exhibition, just to register the fact that there were these violences in this war, but I show them unembellished.

I do not do the interventions that I did with the colonial pictures of military action, because I just don't know that it's right to do so. With the rest of the colonial archive, you could say I've cast a sort of disobedient gaze and reinterpreted things, and I'm trying to use that material to re-narrate this war and tell the other side of the story.

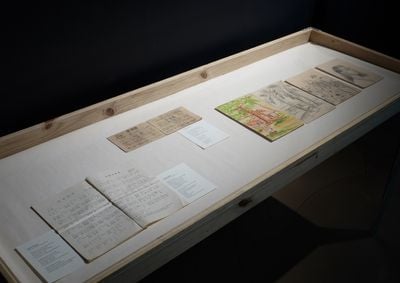

It's a bit frustrating for me, because I'm still using the master's tools to try and dismantle the master's house,5 which is probably impossible, but it is all we have. To balance that, I have these other elements of the counter-archive that I've made on my own by doing 35 oral history interviews with former leftist fighters spread out over five countries over the past several years.

The objects you see here are things that they kept from the war and some of them are individual people's things. Some of them come from certain platoons in the guerrilla army. I also created a two-channel video installation of the songs that they remember from this war. The intention is that the songs flood the entire gallery, even as you look at the colonial representation of it.

So, this is where I'm at currently. This is all I can do as a researcher/artist, which is to try and re-narrate using the material that either I make, or re-make, from the colonial archive, and with other stuff that I've counter-collected. That's my little effort in re-narrating, and that brings us to the big theme of memory and remembering, and restitution of some sort.

It's a bit frustrating for me, because I'm still using the master's tools to try and dismantle the master's house, which is probably impossible, but it is all we have.

There's one part at the start of your book, and I'll just read a little bit: 'She can hear the dead growing louder: we must be heard. We must be remembered. We must be known. We will not rest until we have been mourned. She opens the box.'6

I wonder if you can speak a bit about the constructions of public memory and how they are informed by these archives?

MMI've thought a lot about what these colonial photographs are supposed to represent. I've begun to think of these images and even maybe those post-mortem images as self-portraits of the photographer; that these images are really not the person in the image, they're a photograph of power, and that power is held in the hand of the photographer. It is a reflection.

These photographs are of the British Empire and British power. The human being in each photograph is supposed to be irrelevant, but it's when someone like you looks at it that the relevance starts to really emerge.

The images of Ethiopians that were taken by Italians in the war were supposed to represent Italian might. Even if those photographs depict someone who is a warrior and who may have a rifle or a spear, what that photo is actually transmitting is: I am an Italian, I am in this human being's land, he has a rifle and he cannot kill me.

Every picture trumpets that kind of power, and I think about the ways that memory begins to counteract against that narrative. The photographs don't counteract. Their story is not finished until someone else who knows better stands in front of them and begins to speak against what's been done.

MMMy novel begins with a woman trying not to remember something and yet memories continue to come up. What is it that we remember and what are those things that we cannot forget, even if we try to forget?

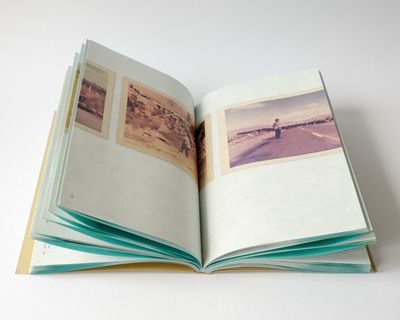

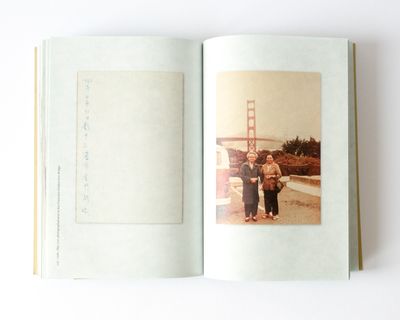

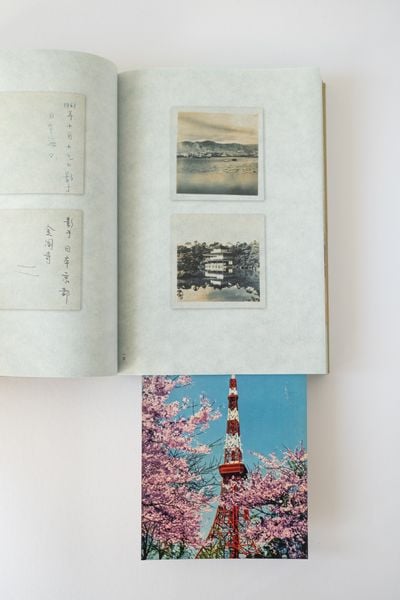

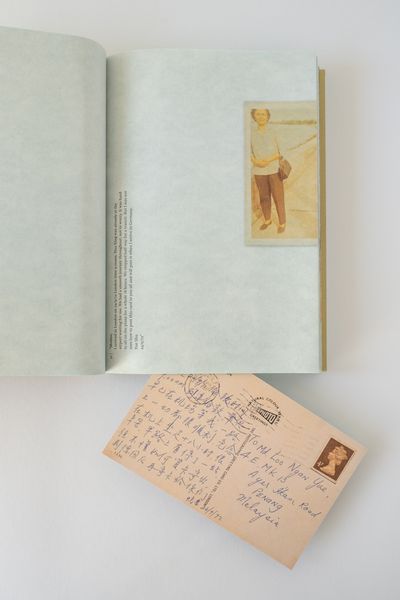

I think the book is about memory, but the flipside of memory is not forgetting—it's the inability to forget. I was struck by that with your beautiful photo book. This is a story of your grandmother, She Never Rode that Trishaw Again. There are pockets in the book, and inside will be writing and also some postcards slipped inside with writing on the back, reproductions of family postcards.

Chi Yin, could you talk about your grandmother's story, and the way that you constructed the book? Because it functions very much in a way that I think memory works and family secrets work, which is always a story on the back side, covered up by something else.

SCYI worked with a designer in Amsterdam, Teun van der Heijden, over the course of a couple of years. We were actually trying to produce another book about my grandfather and then it emerged that my grandmother has her own story to tell, so we decided to use that as the first of three books and this is intended as a prologue to the series.

The book is constructed such that there's a sense of discovery and a sense of a hidden story, literally between the pages. I've used the visual device of vacation photographs, so the pictures are mostly cheerful and happy, and they work against pieces of text that are much heavier and more moving, in a way.

They are pieces of oral history interviews that I did with her oldest son, recalling the lifelong trauma that she lived with after she was widowed during the Cold War when her husband was executed for his politics. There are so many gaps in the narrative for her story, because, like I said earlier, I never knew her and I couldn't figure out how else to fill in those gaps, but with artistic licence you can make a book like that and sort of let the silences almost stand on their own.

It's an attempt to pay tribute to all the women who lost their partners and spouses in the decolonisation wars. I do think that we're at the tail end of being able to bottle these histories from all the decolonisation wars that happened across the so-called 'Third World'.

This is my one little attempt at doing it through the prism of my family history, but I think it should resonate more widely with different people with their own histories. I mean I think we all have skeletons in our family histories wherever we are from.

MMThis is the first of three books—could you tell us about the two others?

SCYI went to the designer to make one book, but then over the years collected more and more material, and he said, 'Stop, we can't make one book now, we're going to make four books.'

I think we're going to stop at three, if we can. The other two books haven't been made yet, because I'm so slow. But the idea is that the second book will take in the main pieces of this project, a wider look at the Malayan war, but through the prism of my grandfather and what happened to him.

And the third book is meant to deal more with the colonial archive and the counter-archive that I've made with these 35 individuals that I've gone and photographed and interviewed and filmed.

This first book has been self-published, because I wanted to keep artistic control of the production, and these books are costly to produce, so there's a lot of fundraising and seeking out support in addition to the creative work.

With that in mind, maybe we should close up by giving some thought to history, historiography, and memory and these small attempts by individuals like you and me trying to re-narrate pieces of what has been prescribed to by colonial archives. There are more and more artists and writers and other practitioners chipping away at this meta-narrative of what happened.

MMLately I've been thinking about a quote by Walter Benjamin who said: 'not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.'

I thought a lot about that when Trump was president, about what would it mean, not only to the future but to the past, if he won another election.

I think that we are going through a very interesting time in the world right now with the rise of the right and conservatism, and there's a responsibility that writers and artists have. Not only to the future, not only to those who are not yet born, but to those that have passed; to the dead and how we speak of them. —[O]

1 Sim Chi Yin, One Day We'll Understand, performative reading text, 2018–ongoing.

2 Maaza Mengiste: The Shadow King, New York: Canongate Books, 2019, p. 298.

3 Ibid, p. 261.

4 Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence, New York: Verso, 2004, preface.

5 Audre Lorde, 'The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House', pp. 94–101, in: Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua (eds), This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, New York: Kitchen Table Press, 1983.

6 Mengiste, The Shadow King, p. 6.