Sophia Al-Maria: The Girl Who Fell to Earth

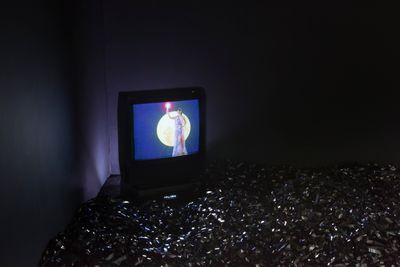

Sophia Al-Maria. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Laura Cugusi.

Sophia Al-Maria. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Laura Cugusi.

In the East London apartment where Sophia Al-Maria lives, a large bookshelf covers one of the walls. Both apartment and bookshelf belong to the translator Yasmine Seale who, Al-Maria reminds me, has recently completed a new translation of Aladdin and is currently translating One Thousand and One Nights. How Al-Maria came to call this apartment home while assuming the role of guardian to Seale's collection of books is, like much of the artist's creative life, a story wrapped in equal parts fortuity and an openness to what she calls a 'certain kind of magic'.

While discussing the act of spiralling, Al-Maria's eyes land on a book behind me titled Spirals: The Whirled Image in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art (2017) by Nico Israel. It's the first time she's noticed the book. As it happens, her new commission for the Serpentine Galleries—a sculpture in the form of a public stage, which will be titled Tarraxos—originates from the spiralling pattern of a dandelion seed head.

It's moments like these that mark the 'magic' that Al-Maria refers to—a term that might just as easily be used to describe coming across the right book at the right time, as it might be applied to finding the right interlocutors in moments of creative inertia. But an openness of mind, I soon learn, is the key ingredient to how the Qatari-American artist, writer, and filmmaker makes something of such moments of possibility.

'I've come out of a period of extreme anxiety and fear of the future, into one of feeling hopeful through being open to change,' says Al-Maria. 'It's not that there's nothing to lose. At some point it becomes clear there's nothing to have.' At a Q&A for her most recent work, Beast Type Song (2019) at Tate Britain, where it is showing until 23 February 2020, Al-Maria glossed over the racism and homophobia that shrouded her experience as a writer for television in the U.K., careful not to give too jaundiced an account of the sordid affair.

Al-Maria has been a screenwriter for several years, but is only recently returning after a hiatus. Beast Type Song, when taken as the acronym B.T.S., hints at the preoccupations emerging out of this other side of Al-Maria's professional life—one which has been made to connect with her own art in ways as profoundly cathartic as they are puckishly stylised.

The act of reading collectively is central to this new work. Over the course of Beast Type Song's 38 minutes, the Lebanese actor Yumna Marwan excerpts In Tangier (2010) by Mohamed Choukri; the British-Nigerian performer Elizabeth Peace quotes from her own dissertation—a postcolonial study of gay life in central Africa; the French-Algerian filmmaker Farida Khelfa reads from Unthinking Eurocentrism (1994) by Ella Shohat, and Al-Maria recites passages from Caliban's Daughter: The Tempest and the Teapot (1991) by the gay Jamaican-American writer Michelle Cliff. Central to the film, however, is Etel Adnan's epic 1989 war poem The Arab Apocalypse, read by the performance artist boychild. Like Adnan's poem, which uses graphic marks and small glyph-like symbols on the page, Al-Maria shuttles between the written word and a more gestural idiom, whose charge finds its most lucid, kinesthetic expression in boychild's drone-recorded dance.

Unsurprisingly, when describing the process of creating Beast Type Song, much of which was made in response to colonisation and various other forms of structural violence, Al-Maria uses terms that are evocatively visceral and bodily. 'There were all these subjects, phrases, quotations, images, locations, and snippets of videos that had accrued in some tract and needed to be cleaned out', she explained in an interview for Artforum. 'Beast Type Song was like a nasty hacking cough that turned into a beastly roar.'

Ahead of Bitch Omega, her first solo exhibition in Germany that opens at Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf this March, Al-Maria discusses her relationship to literature, screenwriting, and poetry; the significance of editing to her practice, and her forthcoming commission for the Serpentine Galleries, set to launch in summer 2020.

TJMWhen you studied comparative literature at the American University in Cairo, did you have a particular focus?

SAMI had particular interests, but it was an undergraduate degree, so it was quite general. There was a lot of reading of Arab and African novels, which I'm grateful for. It was a canon outside of the western canon. I had professors who were really broad in terms of what they considered important for us to read, and they would also come with their own particular author-interests. One of the professors had done Chinese literary translations, so we read a lot of Chinese novels, for example. That is, I suppose, where my interests really went and stayed. I was really interested in pre-Islamic poetry and still am.

TJMHow did visual art and filmmaking come into play?

SAMMike Vazquez—who was and still is an editor at Bidoun—was actually the first person to encourage me to write, and he suggested a course that Kodwo Eshun [of The Otolith Group] had started at Goldsmiths. I thought it was a production course, since it was called 'Aural and Visual Cultures'. Right after college, I was trying to be a video editor; I was working in a book store and also as an assistant editor. I had given up on trying to live in the U.S., where I was for a little while after Cairo. I didn't have all the apparatus it took to be a person there. For example, I had no credit history, because I had never lived off anything other than cash in Egypt. I was giving up when my roommate called and said: 'There's this envelope from the university in London. Do you want me to open it?'

TJMWhat would you have done if you hadn't received that invitation from Goldsmiths?

SAMI had delusions of grandeur that I'd write a young adult fantasy novel based on pre-Islamic poetry: a sort of pan-dimensional mythic quest with a lot of djinn, like Harry Potter or His Dark Materials, but based on non-western magic. A lot of poetry I was obsessed with at university involved spirits, ghosts, animals, and witchcraft, so I wanted to do something with those things. I still want to write it someday, but I'm really grateful for Kodwo's course, because even though it wasn't really an art course—it was more of a philosophy course—it completely opened the world to me in a way I never thought was possible.

One amazing task that I had was archiving photographs from the 1990s and early 2000s, when all these artists were coming to Qatar. I remember being really struck by Ala Bashir, whose terrifying art is still really interesting to me. He was Saddam Hussein's surgeon, but he also made these paintings of furniture made of human flesh.

TJMThen after Goldsmiths you went to live in the Gulf?

SAMI was living there after Goldsmiths and working in the contemporary and modern art museum, Mathaf, before it opened. I was working towards opening it with Wassan Al-Khudhairi and Deena Chalabi—both curators working in the States now, and it was really just the three of us at first. There was an existing collection that belonged to Sheikh Hassan [bin Mohammad bin Ali Al Thani], who had really focused his art-collecting on Arab artists. He ran a sort of unofficial residency for a lot of legendary artists from across the region, including Iraq and Sudan. They would stay and work in this villa he owned, which was a kind of private museum slash salon.

One amazing task that I had was archiving photographs from the 1990s and early 2000s, when all these artists were coming to Qatar. I remember being really struck by Ala Bashir, whose terrifying art is still really interesting to me. He was Saddam Hussein's surgeon, but he also made these paintings of furniture made of human flesh. I was also tasked with meeting and interviewing artists like Hassan Sharif or Zineb Sedira—that was my real art education. Having that proximity was, in a weird way, how I got into artmaking.

TJMWhat relationship, if any, has emerged over the years in your work as a writer, editor, and filmmaker?

SAMI fell into film through video editing. I had done a video editing course—one of those New York film school-type things where you get a crash course. It was really great, actually; I learnt how to use editing software in a couple of weeks. It became a way of playing not just with image and sound, but narrative. I think it helped me tremendously in terms of writing because later, when I had to write The Girl Who Fell to Earth (2012), which was four years overdue in fact, that editing background was so useful. For example, the practice of 'logging' and 'binning' footage. I did that in writing, but with themes, anecdotes, photos, and snippets of conversations, which I pulled out as the book began to weave together.

With the series of texts and performances that I created with Victoria Sin, I wanted to cast a constellation of seemingly unrelated memories, rants, poems, videos, and events out into the audience and leave space for them to make the historical connections that I perceive but can't articulate.

One of the first jobs that I had was assisting with the editing of a documentary that involved video cameras that had been sent to five teenagers in Baghdad in 2006. When they sent the tapes back, my job was to log and capture what was happening in each scene and organise them all for the editor. I was ingesting all of this information, and quasi-translating if there was any Arabic in it, and I could start to see how this volume of footage or material coming in could be strung together into the story of a life—albeit a highly expurgated one!

TJMYou were a writer in residence at Whitechapel Gallery in 2018, and as part of this year-long project you explored a series of what were referred to as 'mini-mega narratives' that brought together 'unlikely events, images and thoughts'. What were some of the ideas you looked at over the course of that period and in the culminating exhibition, BCE (12 January 2018–28 April 2019)?

SAMWith the series of texts and performances that I created with Victoria Sin, I wanted to cast a constellation of seemingly unrelated memories, rants, poems, videos, and events out into the audience and leave space for them to make the historical connections that I perceive but can't articulate. For example, the assassination of the first Moroccan aviatrix Touria Chaoui, a medieval gynaecology text, the cover art of an Alice Coltrane album, and a poop emoji pillow found in the gun aisle of a U.S. supermarket. While I read, Victoria Sin tattooed my grandmother's brand onto my head. It was like writing and performing pieces of a puzzle for the reader and audience and myself to put together, together.

TJMThere's a section in your latest film, Beast Type Song, which includes an excerpt of voicemail from your mother. I'm curious about the significance of the image that accompanies her voice when she speaks.

SAMThe image is a poster by Palestinian artist, Abdel Rahman Al Muzain. In that part of the film, my mother is talking about a poster we had in our apartment. She described it as having a striking image of a Palestinian woman, and the poster by Abdel Rahman Al Muzain made sense, date-wise—there's something familiar about it. In the centre of the poster, there's this folkloric character who is surrounded by different figures who resemble a calligrapher, a cameraperson, and a painter. So there's poetry, film, and art surrounding this character, who represents the homeland—the motherland. Amidst all that, there are also these little political slogans like, 'Jerusalem is Palestine'. I found that to be a really potent reference for Beast Type Song, because the underlying theme is very explicitly colonialism, which is why there's reference to Caliban's Daughter: The Tempest and the Teapot by Michelle Cliff.

I am interested in the way that a 'weed' like the dandelion propagates, and how that might be a model for ways of seeding those difficult-to-articulate thoughts and feels through movement or meditation.

There's this amazing thing online called The Palestinian Poster Project Archives, which has all of these posters—not just from Palestine, but from all over the world—that were being printed in solidarity. A lot of the posters contain graphic art and there would be commissioned artists, especially Palestinian artists, and other Arab artists. There are recurring symbols in these, such as the dove, which became a prominent motif in Beast Type Song and remains an important one for me.

TJMYou were recently commissioned to produce a new work for the Serpentine Galleries, which will be launched in summer 2020. What can we expect as part of this work?

SAMI'm building a stage called Tarraxos, which will be my first outdoor sculpture. It's intended as a foil to the ranting space at speaker's corner a little way across the park. Tarraxos will essentially be a soap box for those who want to use non-verbal communication. The work involves a geometric pattern akin to a dandelion clock. I am interested in the way that a 'weed' like the dandelion propagates, and how that might be a model for ways of seeding those difficult-to-articulate thoughts and feels through movement or meditation. I am in awe of the way in which dance can open time and space and can communicate so clearly without a single word. This is why I invited boychild to inaugurate the stage. Her work is a tremendous inspiration to me, and so the piece wants to be a kind of amplifier for the performance she'll bring, and a beacon and portal for anyone who comes to use it after. —[O]