Thukral and Tagra

Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra. Courtesy the artists.

Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra. Courtesy the artists.

Over the past 15 years, Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra have developed a collaborative practice of painting, sculpture, design, installation, interactive games, and experimental participatory exercises. Their work spans a range of interests and subject matter: from their early explorations into globalised consumer culture and diasporic Indian communities, to a recent introspection on symbolism and meaning in Hindu mythology. Their unique approach tries to break down complex cultural matter into something that is experiential, interactive, and even playful for their audience—as exemplified by Bread, Circuses & TBD, an exhibition of paintings and an interactive game that inaugurates The Weston, a brand new visitor centre and gallery at Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP), designed by London architects Feilden Fowles (30 March–1 September 2019).

Developing the exhibition in tandem with the gallery's construction, the artists had the opportunity to work closely with curator Helen Pheby to design the exhibition as a response to the light-filled glass and concrete structure, which is subtly embedded into the natural landscape. The exhibition was also inspired by the Don Pavey Collection of art and games, which is held at the National Arts Education Archive at YSP. Through research into Pavey's collection, Thukral and Tagra sought to apply a certain logic of organisation and movement that could help the audience encounter the complex data on the agrarian situation in India that is the spine of this project. The focus of this exhibition is the devastating issue of farmers driven to take their own lives as the only way out of crippling debt. The narrative of struggle is here told through the analogy of the kushti (a traditional form of wrestling) of rural Punjab, which is closely linked to the farming communities through local akhadas (community gyms). The absence of the farmer's figure in Bread, Circuses & TBD calls attention to the disappearing body of the farmer across the Indian landscape.

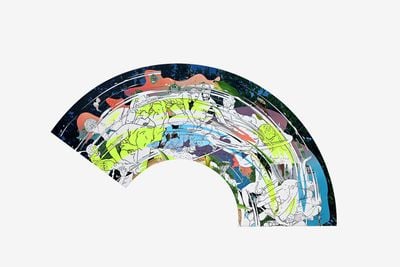

At the centrepiece of Bread, Circuses & TBD is a game based on kushti, through a round wrestling mat marked with different symbols and numbers installed on the floor. Viewers are invited to immerse themselves into the farmer's struggle by momentarily adopting a 'pose' read from the corresponding key on the wall. As the players go through the manoeuvres, they learn about the different challenges experienced by the farming community and temporarily implicate their bodies in a struggle against an invisible force. Surrounding this game board, seven large pieces formed from a single, circular canvas are mounted on the walls. Within the paintings there is a dense, layered visual narrative in which one encounters a collage of elements, symbols, and styles. Hyperrealistic depictions of grains, trees, and natural elements are foregrounded by comic book-like sketches of wrestlers writhing in contorted formations on the ground. The wrestlers, much like the paintings themselves, seem immune to the pull of gravity: arms, limbs, and torsos all flail helplessly without the once-stable earth beneath them.

In this conversation, Thukral and Tagra discuss their role as artists and how they are responding to what they deem as one of the greatest socio-economic crises of our times.

SCWhere did your interest in sports and games first begin?

TTST: Our interest in sports and of looking at their aesthetics developed very early on when we did the exhibition Match Fixed/Fixed Match at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in 2010. The project developed while we were doing our research on the Indian diaspora. We encountered the Doaba region in Punjab, where there were over 30,000 reported cases of women who have been abandoned by their NRI [non-resident Indian] husbands. These girls are trying to live out their dream of 'going abroad' and end up getting married to these NRIs who come on a holiday to India for three to six months. They live and spend time in the women's houses, make a lot of false promises, and end up going back and disappearing. This actually came to us as an idea of 'match fixed, fixed match' because of the location of two entry points in a square space. We wanted to play on the idea of the arranged marriage through the metaphor of a manipulated game of sports, so we decided to turn the whole exhibition space into a kabaddi match. We had six life-sized golden trophies to represent the idea that these NRI husbands were life-sized 'catches'. On the other side were interviews with some of these women who had been abandoned by their short-term husbands. We documented their stories with the help of shaadi wala video people [local wedding videographer companies], because we knew we needed an intermediary to help us speak to these women. That work is actually showing again after almost a decade's gap at Le Tripostal in Lille in April 2019. Our vocabulary of games has extended so much since this first project, so we are interested to see how this older work will be received after a long break.

SCSince Match Fixed/Fixed Match, you have had several projects that have referred to games or used the metaphor of sport to tell another story. It was not until Games People Play at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Mumbai (19 April 2015–28 July 2015), that you really started to explore the history of Indian games and develop your own methods and rules for play within the vocabulary of your exhibitions.

TTST: Match Fixed/Fixed Match was our first scaled up exhibition where we were trying to juxtapose two seemingly unconnected things. From this point on, the entire dialogue between sport, game, and the aspirational nature of middle-class Indians actually became a really large exercise and we could see scope to develop it further. On one side we have this very painful narrative about aspiration and middle-class Indian dreams. On the other side was the idea of sports, the idea of playing, and the act of making the 'rule sets', which normally govern the play, but in this instance govern the experience of viewing an artwork. It is also interesting for us to think of the moment of witnessing something. A game is like a mega-event that is happening, and as the audience, everyone is present to bear witness to the play. I think we are also attracted to the spectacle of the game. We've always said that the exhibition should look like a powerful magnet to bring people together. We like to imagine that our exhibition could give the feeling of a 'mega-event', which is very close to the feeling of a sporting event, with people queued up outside the arena or thriving on the energy of the players. We respond to this idea of a mega-spectacle, and that's where the idea of scale comes into our work. Our continued interest in games, play, and sport comes from a point of view of taking the complexity of social issues and refreshing the way one approaches this subject matter. We are not reporters, nor are we social activists in the normal sense. We're trying to figure out how an artistic process elaborates these complex social issues. I think that's the key aspect.

SCJiten, your father is a very well-known and well-respected akhada wrestler in your hometown of Jalandhar. There is a long, personal family history here, but you always say you never liked sports and games. Does your personal history inspire, or perhaps help you to problematise the place of sports in the cultural landscape of Punjab?

TTJT: Professionally, my dad is an artist and managed a studio of painters in Jalandhar, but his other passion is wrestling. The akhada that appears in our film Q (2013) is the base of our interest in wrestling. This akhada is managed and looked after by my dad and his four friends. It has a very interesting story: the land was given to them after partition, and they were charged with using it as a non-commercial space. Through the akhada they are trying to keep the wrestling tradition alive.

When I was growing up, I was used to seeing people all around me paying to use the gym. Every month they paid a fee to use the equipment. In Jalandhar, every gym was free for me because of my father. I was allowed to go to any sports complex or participate in any academy for free. But in reality I never went to an academy, I always hated it, and I didn't want to go. We used to get free equipment because of my other family members, who were manufacturers of school sporting goods and kit bags. Jalandhar has some of the largest manufacturers of sports goods from India. Up until I was in sixth or seventh grade, my dad would take me to the akhada almost every day. We used to exercise and even have our daily showers there. It was a huge part of my life as a child. But the more I grew up, the more I started hating it; but maybe through our paintings, I have started to develop a new relationship with this history.

SCBread, Circuses & TBD looks at the social condition and the livelihood of the wrestlers. Can you explain a bit more about the relationship between wrestling and farming?

TTJT: The project refers to a general routine practised by the people of Punjab who are—broadly speaking—a farming community. There were no 'gyms' as we now know them. Those only started in the 1990s. Before that, people used to go to local community gyms like akhadas, where they would exercise through kushti. There wasn't just one akhada, either. There used to be at least 10 or 15 spread out across every city. The various akhadas in the cities would enter league-style kushti competitions called dangals. The dangals were divided by their own logic of hierarchy, such as weight, or age of the wrestler. The highest category was called pagdi, which recognised the former champion's turban. Previous dangal winners were given a piece of cloth or fabric, which they tied around their head as a pagdi, which showed their status. Now, of course, the system has changed and you win a lot of prizes, like a bike, a car, a tractor, or a cow! The bike and car actually came much later on, in the 2000s, when the sport of kabaddi became very big. Why a cow as a prize for kushti? This is the essential link of Farmer is a Wrestler (2019), which was an earlier iteration of this exhibition, shown at the Punjab Lalit Kala Academy, Chandigarh. A cow is given as a prize so that the winner can sustain themselves. And you must imagine, if someone is being gifted a cow, the assumption is that he knows how to take care of the cow. All the people who own cows are not shehri [city folk], but farmers—village people. Early morning, they would get up and cut the fasal and chara [crops and grains] and then go to the mandi [wholesale market] to trade and sell their wares. After this, they would meet at the local gym. The akhada became a meeting ground for these communities.

SCCan you explain a little about the intertwined history of Sikhism and the history of Punjab? How do you see this affecting your research and your work?

TTJT: Punjab is the birthplace of Guru Nanak Sahib and Sikhism, which is the fifth largest religion at present. I grew up in a multi-religious household, where we practised different cultural elements of different religions. This included Sikhism, which is of course a dominant faith and is very closely linked to the history of the region, and therefore to the subject of Farmer is a Wrestler itself. Wrestling is a popular sport in Punjab as it fits naturally with the tradition of agriculture. Both activities assess the strength of body and mind. In fact, the second Sikh Guru Angad Dev established many mal akhara [wrestling grounds] so that followers could harness the human strengths needed for an honourable life. I feel that is where the belief that the Sikh are a 'martial race' or a warrior class who are trained to fight, stems from. Sikhism also has a very particular and complex relationship with the idea of battle, and one can see the legacy of this in different fighting techniques still practised today in gatka, which is an ancient martial art associated with Sikhism. The main thing to understand here is that the history of this land and its people is an agricultural history and a martial history. The techniques of martial arts used in battle also trickled down into the akhadas. The akhadas were a place for exercise and entertainment, but they were also a serious training ground.

In our paintings in Bread, Circuses & TBD we are trying to draw out the parallels in the physical gestures used by the wrestler and by the farmer. For instance, godna is a practice of aerating the soil by hand to make it more fertile for crops. The wrestlers of the akhadas [wrestling grounds] practice the very same motion of 'shaking' the soil by hand before engaging in kushti to ensure the soil is soft before it touches the skin. The physical action is identical.

SCWhen you started your research into this project, you decided to work on a '100-point agenda', which relates to challenges of agriculture worldwide. It seems that many of these topics are addressed with Indian problems, however.

TTJT: We didn't just want to address the issue from an Indian perspective—we wanted to address this as a global issue around farming crises. In India, one of the most basic crises is the arhtiya, or middleman. A farmer can't access formal or government structures to secure loans for matters such as education and access. So they end up going to arhtiya, which eats up most of the money, leaving the farmer in debt. This is happening on a small scale in India. Internationally, the same transactions take place on a much larger scale. The arhtiya might be a company that puts pressure on farmers to grow certain crops. For instance, farmers in the U.S. are educated about the land and about biodiversity, yet they only grow corn because of external demand and pressure!

ST: The language within the artwork doesn't just apply to a localised context—it opens up a much larger, cyclical dialogue of which we are all part. We want to create something that any person can respond to, based on their own personal experience or level of understanding. The problem we describe is largely a misunderstanding about food resources and how the farmer is struggling in today's economy.

SCAs you have just explained, the work builds up from a long and detailed narrative that derives from the history of Indian sport, religion, and sociopolitical history. There is a rich cultural reading that can be interpreted from these paintings. Do you think these specificities are accessible to an international audience? Are there elements in the show that you've included as devices for translation?

TTST: We have decided to make this wrestling ground on the floor. It's a game, or performative piece, that sits in the very centre of the exhibition. The mat is divided into seven parts, as there are seven canvases and seven broad categories through which we have organised the main issues as we see them. Each can be seen as a level of comprehending the entire problem. The participant can actually be a part of the exhibition space, and feel that he has actually touched the subject matter. In this game, we decided not to show the wrestling in a direct way, and instead ask people to come in and 'bout' with an invisible set of circumstances, which are really important to this narrative as a way to understand and comprehend what it feels like to be a farmer, and what he is going through. Also, there is this instructional choreography, which is interesting in the way that you get 'magnetised' to the rules. The game is a self-motivated activity to learn different moves of wrestling, in response to the issues of farming faced today. If the player is able to complete all seven manoeuvres, he is awarded a stamp of completion, which certifies his sincerity of trying to understand and comprehend this situation.

SCWhat is the role of interaction and participation in your larger body of work? What kind of experience do you hope to create for your viewers? I'm thinking about the development of this intention from one of your earliest projects, PEHNO - Put it On (2010), and how you managed to get a general public to start discussing an extremely taboo topic of aids and safe sex, through an intervention of selling instructional flip-flops at a street market stall in New Delhi!

TTJT: PEHNO - Put it On was probably when we started thinking about how to cut out the 'middleman' in communication. We realised that even though people might be receiving information via the TV or newspapers, they don't always really receive it until there is a significant moment of exchange or information sinking in. PEHNO - Put it On was our first experiment on how to make a viewer actually act out something rather than just read it. It became a way for us to get a message across in a very different way.

SCI'd like to talk to you about how you see your ethical responsibility towards the people whose lives you are depicting in Bread, Circuses & TBD. You've been given incredible access to the private and painful details of these farmers lives. You've had the opportunity to speak directly with family members whose loved ones have committed suicide over the burden of their debt. You've been into their homes to research, understand, and document their experience. How do you make sense of representing their stories in your exhibitions, and what do you hope might change or improve in their lives because of these exhibitions?

TTST: Meeting with these families was a ground check—a primary hearing from the victims fuelled the depth in the process. Being privileged, we don't understand what it means to live in a situation of pain. We never wanted to use the pictures of people, as we didn't feel right to intrude on their pain. Rather, our research and our work is an attempt to absorb and comprehend and to try to find alternatives to narrate the issue. From the beginning, we felt the process of addressing this should be an honest approach to understanding the problem. It does come in layers and we try to understand and take the measure of the situation, but also think of limitations, as this is probably the biggest issue of our times.

The project has quietly been developing for many years in our studio in Punjab, and we work closely alongside social service organisations in Punjab who try and help the widowed wives of the deceased and their families. They are the ones who helped us in our research, and we continue to try and support them as they are trying to save families who are in similar situations. We are thinking about how to free kitchens in some of the affected villages as a way to provide employment for the widows and of course as a place where the families can also get fed. They have to help develop economically self-sustaining models, as any monetary donation we make will only go so far. We have a few iterations of this exhibition planned in India in the coming year, and we hope to work with the free kitchens in some way. —[O]