Trinh T. Minh-ha and Irit Rogoff on Feminist Aesthetics and Cinematic Reflexivity

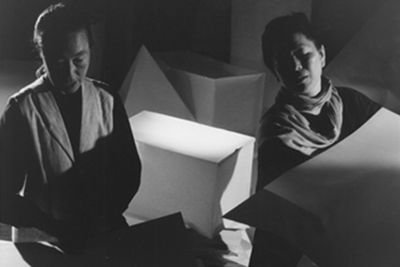

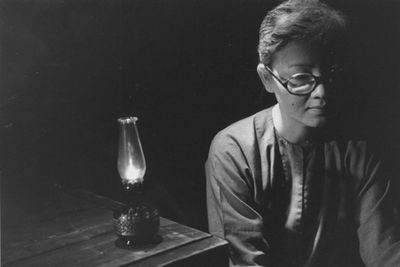

Trinh T. Minh-ha. Courtesy the artist.

Trinh T. Minh-ha. Courtesy the artist.

Vietnamese-born Trinh T. Minh-ha is a writer, theorist, composer, and filmmaker whose practice, spanning some 30 years, is positioned within the fields of feminist and postcolonial studies.

A professor of Rhetoric and of Gender and Women's Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, Trinh studied music composition, French literature, and ethnomusicology at the University of Illinois after leaving Vietnam during the country's war in 1970 at the age of 17.

As an exchange student, she attended the Sorbonne Paris-IV, and after finishing her PhD, she went on to teach in Dakar, Senegal for three years. Senegal was the focus of Trinh's first 16mm film, Reassemblage (1982), which documents the lives of women in rural Senegal.

Reassemblage exemplifies the way the filmmaker approaches the subjects portrayed in her films—a position she has described as 'speaking nearby' rather than 'speaking about'. Trinh posits her works as 'boundary events', existing in a zone between labels—a place where new labels might form or dissolve or cross over one another, and which allows her works to evade categorisation. This is enhanced by reflexive cinematic techniques and editorial processes that challenge the traditional documentary form and deconstruct modes of thinking and looking at different cultures.

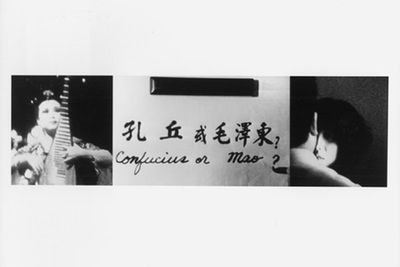

A multi-layered enquiry into the shifting culture and politics of China post-1989, Trinh's 1992 film Shoot For The Contents is distinctive of the filmmaker's approach to cinema as a means of deconstructing modes of thinking and seeing.

This intricate, cinematic layering reflects on a statement made by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1956, 'Let a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend', and enters a complex and poetic exploration into questions of power and change, politics and culture against the backdrop of the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989. Infusing popular songs and classical music, as well as intimate footage of various subjects and stylised interviews—the film confounds viewers who seek a traditional, informative documentary format and offers instead an insight into the creative processes of filmmaking.

Between 2 and 9 December 2017, the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London presented a retrospective programme of Trinh's work. The following interview is an edited transcript of a discussion held between Professor of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, Irit Rogoff, and the artist on 7 December 2017 as part of this programme. The conversation touches on issues of post-colonialism, 'feminist aesthetics', and cinematic reflexivity, and is the second of two discussions that took place as part of the ICA Retrospective.

These conversations are being published in the lead-up to Art Basel in Hong Kong this March, when ICA with M+ and Hong Kong Arts Centre will present Films by Trinh T. Minh-Ha at the Hong Kong Arts Centre, building on the recent retrospective at the ICA in London. This programme is organised in collaboration with the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies, Faculty of Arts, Chinese University of Hong Kong, and in association with Art Basel Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong screenings will be followed by two discussions. On 28 March, a screening of The Fourth Dimension will be followed by a conversation between Trinh and artist Wolfgang Tillmans, chaired by artist Linda Chiu-han Lai. On 29 March, Trinh will be speaking with Professor Jia Tan and researcher Chương-Đài Võ after screenings of Forgetting Vietnam and Reassemblage.

IRI wanted to start by unpacking your film, Shoot For The Contents (1992), in which there is this extraordinary layering of all kinds of knowledge—mythological, folkloristic, philosophical, poetic, urban, rural, as well as both popular and high culture elements.

Everything seems to operate as an effort to grasp something about this enormity that can't be grasped. Though it's not the fact that it's ungraspable, it's the fact that nothing can be reduced to a single identity. Can you discuss this process of layering?

TMYes, I must say that the reason I work with the dragon as a symbol of power is mainly because it has, as an image, gone through many stages. The dragon is supposed to be an animal of peoples' imagination, but somehow, in the process, it was appropriated as the symbol of power in imperial courts in China, and people were then forbidden to use dragons on their clothes or on furniture, or whatever they might have come up with.

Of course, people didn't go by that rule, because the dragon is an animal that was created by the imagination of the people. And to continue on what you said, this is really the symbol of the people, so why would power appropriate it for itself?

So people continued to use the dragon in their symbolism, and later on, the five-clawed dragon became the image of imperial might, while the four or three-clawed dragon was renamed accordingly when used among people. As you can see, the politics of naming and representation arises even with the image of an animal like the dragon.

When I was working in China after the Tiananmen Square event, people were very much on edge and were also very suspicious of someone like myself, because at the time there was ongoing conflict between Vietnam and China.

As long as they didn't ask anything it was fine, because they would just think I was from Beijing and that I didn't speak any of the dialects from the province. But as soon as they found out I'm from Vietnam, people would look at me as though they couldn't believe they were in front of the enemy.

It was a very specific moment in China's history, and one could see it as a trial phase, with much effort to grasp and hold on to something.

At the time, everyone was trying to understand why this massacre of students and workers had happened, and there were many assumptions. But for me, it's mainly that I didn't want to give knowledge to any one faction or to let knowledge of one faction dominate. So that's why you have this variety and multiplicity of knowledges and positions that coexist without anyone being on top or having the last word.

IRShoot For The Contents is suspended between, on the one hand, essentialist identity politics that tie down an identity with a very particular representation or a very narrow understanding; and on the other, the entire gamut of postcolonial study and theory that was very present at the time.

The period in which we knew each other well, the nineties in California, was suspended between these two things. How do you place your practice between these two?

TMMy book Woman, Native, Other (1989) is very critical of identity and closure; but after finishing it, I encountered many good people who are precisely on the side of raising strong boundaries in terms of identity politics, and I had to step back and accept the fact that these enclosures are created in a very situated context.

Depending on the context, why would people come up with these kinds of boundaries? Not only in relation to the other but also for themselves? Every wall that is put up is a wall against the other, but also a wall that confines oneself. I had to take that into consideration.

The way that I understand postcoloniality is very different from what people attribute to that term. My take on postcoloniality corresponds very well to what today's decoloniality has claimed. The question of decolonalisation can be thought of in relation to the sixties, because that's when nations in Africa gained independence.

There are so many things that were written on decolonalisation, and then suddenly more recently, you have people starting to reclaim the term decolonalisation; it's very weird. But it's something that comes as a kind of cycle.

For me, the 'post' of 'postcoloniality' has to be put in the context of a notion of time that is not linear. If you put it in the context of linearity then you can say that 'post' comes after colonialism, and is also situated geographically—related only to the countries that have been colonised. But postcoloniality happens now, all the time, right in the White House. Some people might say postcoloniality is over, but it is absolutely not over and has actually spread much wider than the confines that one tends to give colonialism.

Colonialism is not merely specific to a period and a location. It is widespread and persistent and determines the way that we presently think. That's why in relation to the film, I would definitely not only work with my own relation with China, which is a relation of coloniser and colonised.

If I am in Vietnam, that relationship is definitely an antagonistic one, but if I'm in the West, then I can stand with China, because there is a certain solidarity—and the way I bring in the figure of the Black interviewee Claremont in the film is precisely for that kind of solidarity: South-South.

IRThere is a recapitulation of a very traditional kind of colonial perspective on China as an endless market. I was once interviewed to head a national art academy in the Middle East and at the end of the interview, they asked me if I had any questions and I said, 'I'm actually quite worried that this is a very provincial place; you can't be a national art academy if you're very provincial,' and they said, 'We too are very worried about this, what do you think about China?' And I thought 'China? For this art academy in the Middle East, what's it got to do with China?' And then I understood that China defined their notion of an international or a global market.

TMIn the example that you give, we can say that sometimes—as related to marginalised and oppressed peoples—you are given the worst to live with and when you revolt against it you actually accept it in order to re-appropriate it to your own ends.

If China has been associated with commerce or trade, it's because that's the part China has also taken on, developed, and has tried to run with even faster than the West, which is a way of turning back and beating the master at his own game. This is what China has picked up and pushes to the maximum in its drive towards modernisation.

IRIn several of your films that deal with East Asian histories and identities, like Surname Viet Given Name Nam (1989) and Shoot For The Contents, you put the narrative in the hands of women who live out women's histories in a very specific way and who occupy double and triple positions.

They're traditional characters, contemporary characters, historical, fictional—and there's this slippage all the time, and it's always in the hands of women; it's the women who are performing the multiplicities of identity all the time.

TMI would say there are two ways to approach 'feminist aesthetics' in cinema, and one way is to point towards women as a field of departure. For me, when people talk about feminism as being all about women I would say no. Although it's important to begin with, women as an initial reference from which to depart, ultimately the goal is not merely women—it's the wellbeing of society.

Because of the historical repression of women's voices, we can start somewhere that gives women the agency to narrate their situation or the situation of a country. All around the world, there is this tendency to always make women bear the responsibility of the nation's image. In war, for example, rape is prominent as a way to take vengeance; men often collectively rape women from the enemy's side.

Humiliation of the enemy was always through women. So women are made to bear the honour of a nation and if anything goes wrong, it's their problem. You see that, for example, with Frantz Fanon and 'Algeria Unveiled'—it's incredible to take for granted that women have to bear the image of a nation.

So in that sense, yes: I am committed to putting agency and multiplicity in women's voices and to expanding their roles. But one can always see the other side of a 'feminist aesthetic', which, more importantly, is not only to focus on women. It's to make films for the feminist viewer.

It doesn't matter if the feminist viewer is a man or a woman; if you give yourself that goal, you'll speak, show and tell slightly differently and people can certainly recognise that. Maybe not in a rational way, but you certainly have a difference that is being created just because your goal is not any viewer, but a feminist viewer.

IRGoing back to the notion of decolonisation, I agree with you that there's a cyclical eruption of decolonisations, but this moment of decolonisation is very much about a recognition that a colonial mindset is something that we're still in the grip of, whether we hold the territories and fortunes of other people in our hands or not.

It's a recognition that the West is, despite all the processes of actual decolonisation, still in the grip of a certain colonial mindset that dominates an entire set of cultural values, curricula in universities, and notions of significance and of achievement.

It seems to me that, in that sense, there's a lot of decolonising going on in your films and that that decolonising has to do precisely with the fact that there is no fixed position from which to see something. That the only way to see something is through a multiplicity of positions, of facts and fictions, of political analyses, and giving yourself over to the poetic, to the mythological. You can't just be a 'Western rationalist', you have to be all of those things in order to see something.

TMYes, I think that's very nicely put. Going back to postcoloniality as I expanded on it earlier, if you put it in a linear sense of time then the 'post' is always after. But if you think of time as a spiral, which is how many people in the world receive time, for example among indigenous peoples like the Maori people, the 'post' can be 'pre'; it can be before depending on which way you go.

In that sense, postcoloniality continues to happen over and over again, and in this case there is room for more than one kind of knowledge, and more than one kind of narrative. At the same time, as you refer back to tradition in order to find something different to counter the dominance of Western thought, you are also not caught in tradition; so you have this situation where you are constantly engaged in at least two movements at the same time.

IRIt's one of the fascinating things in the film that you feel the weight of somebody trying to grapple with something that is China and then at the same time an absolute refusal to sustain one way of thinking. Normally, when we are faced with an enormous burden such as class injustice, there's one pathway through which we can organise our political stance militantly; but in your film, you diffuse that one pathway into multiple, myriad pathways and yet the sense of burden remains.

TMThat's something very relevant to mention. You might think of this film as being dated because it was shot just after the Tiananmen Square event. But the situation is still very current, and a main writer, philosopher, and political activist like Liu Xiaobo, who wrote this wonderful poem on June Fourth—because in China it's actually called the June Fourth event, not the Tiananmen Square event—was recently put in prison.

He's the one who got the Nobel Prize in absentia. The chair was left empty, and his absence, and the absence of anyone who could represent him, is very telling of the situation today. So the Tiananmen Square event is what officially the government does not want to be reminded of, and anyone who tries to bring it back to memory has been kept under strict surveillance, if not sent to prison, as Liu Xiaobo was.

IROne of my favourite texts of yours is called 'Cotton and Iron', and it starts with a situation where a storyteller is recounting a tale to a group of listeners but he interrogates the tale, asking, 'Tale, are you truthful?' There's a kind of constant interrogation of the very form which you're enacting and performing.

I wanted to ask you about that within filmic practice: that constant disruption of the ability to comfortably settle in the film and know where you are. In a way, you're asking the film all the time whether it's truthful, whether it has the capacity to convey what it claims.

There's something about not quite giving in to the illusion of film by questioning its voracity, its capacities, and being a little dubious about its ability to create perfect illusion.

TMDefinitely! I think we can see it as a critical approach to cinema, but I think we can also see it simply as a way of tuning in to the nature of cinema, the nature of image.

When I look at myself in the mirror, my image is there where I am not. It's simply the nature of reflection, the nature of an image that you're pointing to.

Thank you very much for that association between the beginning of 'Iron and Cotton' and the questioning of film images. Unfortunately, the reflexivity at work in my films often tends to be confused with a form of breast-beating and of self-criticism.

For me, reflexivity is so much wider because it's not only about yourself. You are yourself a reflective surface, and hence when you are trying to project something to yourself it comes right back to you.

But on the other hand, reflexivity can happen between one element of cinema and another element. Someone tells a story and suddenly someone else without intending it tells another story and the two stories suddenly reflect one another, or one story comments on the other, for example. So that kind of reflexivity again breaks with linearity, and in that reflexivity every time you show and tell something—it shows you, or you show something about yourself.

What we see in an image is a manifestation of how we see in it, so the 'what' and the 'how' are always together, and self-reflexivity is a way of expanding and receiving the world.—[O]

—

The first conversation with filmmaker Xiaolu Guo, was staged at the ICA on 6 December 2017, and can be read here.