Verina Gfader

Verina Gfader. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Stephan Köhler.

Verina Gfader. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Stephan Köhler.

A quick tally of the number of international art book fairs may be all that's required to quell any doubts as to the state of art publishing. This provides temporary respite from the steady stream of new tech gadgets and digital platforms that are nonetheless causing seismic shifts in the creation, production, distribution, and engagement of art in print.

Verina Gfader is among those for whom art publishing still resonates and constitutes a significant part of their work. She received her PhD in 2006 from Central Saint Martins College in London, before pursuing postdoctoral research. Gfader's initial thesis framing fine art animation within a western context led her to focus on Japanese independent animation while at Tokyo University of the Arts (or Geidai), and resulted in her 2011 publication Adventure-Landing. Conceived as both a book work and map, the compendium of conversations with artists, architects and researchers traces animation through its use as an artistic medium of production, while making structural ties to other geographical, institutional, and social concepts. Gfader also conducted research at Aarhus University in Denmark through a project there, entitled 'The Contemporary Condition'. It investigated 'contemporaneity as a defining condition of our historical present [through] contemporary art and experimental artistic practice'—with 'particular interest in the role of contemporary media and computational technologies'—in order to question 'the formation of subjectivity in time and the concept of temporality in the world'.

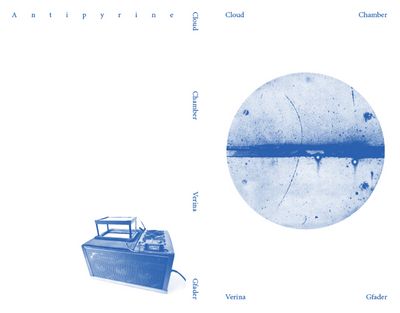

Rooting her overall practice at the nexus of the ephemeral and material, Gfader has at times embedded fiction as a mode of enquiry and used intervention as a strategy to procure a sense of engagement. One example is her recent project, The Guests 做东 (2016). In the performance for the 11th Shanghai Biennale, costumed amateur actors conversed with exhibition visitors in order to generate a 'future folk tale'. The recently published artist book and edited volume Cloud Chamber (2017), is also rooted in the visionary plot of Gfader's performance.

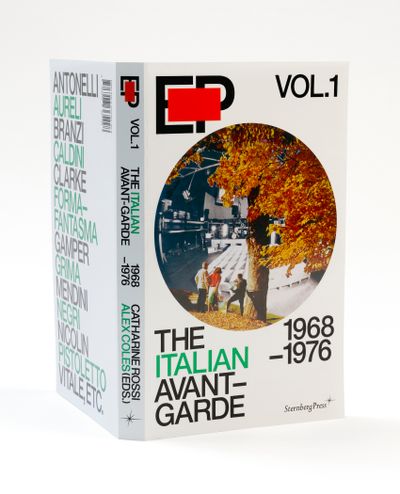

Alongside her work as an artist, Gfader serves as Creative Director for EP, a book series published through Sternberg Press in Berlin spanning art, architecture, and design; volumes include The Italian Avant-Garde: 1968–1976 (2013) and Design Fiction (2016). For Gfader, the capacity for publishing lies in the opportunity to query, mine, and rethink its function as an intermediary between anything from print to performance. This is achieved by orchestrating her practice within organised fields of research aided by drawing, spatial models, text-based performance, and fictional institutions that utilise publishing not as a means to an end, but as a way to contemplate the conditions of how modes of inscription take shape.

This view of art in an expanded context led Gfader to Hong Kong in December 2017, as part of an Asia Art Archive artist residency co-hosted by Spring Workshop. While there, Gfader conducted a talk, 'Wild Iconographies', which was staged in four episodes and was presented with visual aids and print ephemera, as well as a corresponding programme, 'the New Year Intensive'. As a whole, Gfader's AAA programming was conceived as 'an encounter with past magazine movements through today's image worlds unfolding across the material and immaterial'. By channelling the spirit of those spearheading these movements and using performative action and public engagement to do so, Gfader offered a vision for how printed matter could become 'an agent for collective action, social thought, and "world imagining".'

ICBefore this trip to Asia you participated in the 11th Shanghai Biennale (Why Not Ask Again?, 12 November 2016–12 March 2017), with a project entitled The Guests 做东 (2016). The project took place over several days in and around the rest of the works on display, and as a central part of the Biennale.

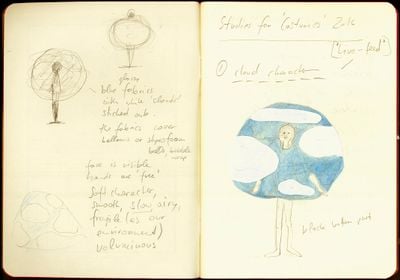

Being new to Asia at that time, how did this influence your choice to formulate an intervention whereby a group of volunteers, ranging in age and dressed up in cloud-inspired costumes, engaged visitors in conversations as a way to produce what you refer to as a 'future folk tale' through this dialogue?

VGI would describe The Guests 做东 (2016) project as a 'performance publication' that functioned as a discreet 'blink and you miss it' event during the Shanghai Biennale. It involved four performers, including one child, who were dressed in specially designed 'cosmological' costumes and equipped with audio recorders. They approached any willing visitors with a particular set of questions. Their scripts also included poetic, partly nonsensical statements that enabled conversations and disputes, as well as stories to emerge. Their responses were then collected, translated, and transformed into a semi-fictional novel—a 'future folk tale'—whereby the audience became its co-producer and co-author.

ICWhat is the difference between a folk tale that already exists and refers to its own oral history each time it is retold, and a folk tale that you qualify as belonging to the future?

VGThe folk tale was a means to meditate on emergent forms of post-literacy, and by exploring the supernatural in our 'post-human' world. At the core of The Guests 做东 was its reference to the rich, mythic, and animistic world from Wu Cheng'en's 1592 novel Journey to the West, and what was left out of the first substantial and most popular English translation by Arthur Waley that was published in 1942, Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China. I had an interest in people's present fears and inner disputes, their manoeuvers and plots in a climate of transnational confusion and heightened sense of un-translatability. How do you find ways out from yourself? Can today's art fundamentally form a space for both real and magical rediscoveries? Perhaps this can be through the imagination, and in formats such as storytelling or animation.

ICYou stated in your Asia Art Archive talk 'Wild Iconographies' that, as an artist and researcher, your work is 'a frozen embodiment of social relations' involving a strong interest in publishing as a way of bringing people together. This got me thinking about the relationship between print and performance.

As a curator, what I've come to understand in terms of the publication as an art form is how artists use publishing as a tool. In some sense, its distributional aspect enables the publication to perform itself by entering into unknown territories and sets of social relations—over time, space, and seemingly endless encounters with people that the artists will never see or meet. How do you conceive of social relations in terms of its role in publishing, performance, and your own practice?

VGI hadn't necessarily thought of my work as being about a network or trying to enact one through an accumulation of social relations. But in relation to the talk, I would say I was pursuing the temporal character of objects, text and image, plus print, so as to consider aspects of time, ephemerality, and suspension; as well as my interest in analog forms in the classic sense that connects to actual, concrete material. All 'stuff', basically, that moved into my engagement with publications.

As I turn more towards printed matter, I think about what it is now, and what its future is. How can we reinvent our relation to books, artists' books, and books in general? Through my Asia Art Archive talk, I tried to address three dynamics: first, print and its reparative function, or its relation to repairing the unseen and hidden; second, print as a discussion of inequality; and third, print's relation to a coherence of a community and as a form of 'world imagining'.

ICIn terms of retaining a classic sensibility, I would say that there's still a respect for printed matter in the region. Asia Art Archive is a good example of an organisation that is rooted in its collection of books and other materials in print alongside its more recent shift in focus on a digital platform; the soon-to-open art and heritage site Tai Kwun and its collection of artists' books from the region is another. So there's definitely a vested interest in retaining material histories.

More broadly, print culture seems alive now more than ever despite any discussions or theorising of the contrary when looking at the art book fair world. What is your experience with working in print? What have you found through your research and what have you experienced in terms of how your projects actually manifest?

VGI am less invested in medium specificity or the idea of overcoming the digital because, as you said, my experience is that more and more books are actually being published and there is increasing hype around all kinds of printed matter. For me, publishing is used as a frame of reference and where printed matter becomes a form of image ecology. So rather than thinking necessarily about a 'book' or a 'text' in definitive terms or within a specific archetype, they function as environments where relations are formed and then re-formed, discussed and then re-discussed. They emerge as communal space. It's like what you touched upon before, about how there is no immediate sense of control over what happens when you put these things out there. Especially with books there is an object somehow whereas within the electronic sphere it's a completely different kind of modality with different possibilities and ways of re-thinking publishing—or print, perhaps.

So the book is less of an object, but more of a discursive platform; an accumulation of desires, and way of bringing people together—or pulling them apart.

ICDo you think about your talks as a form of 'lecture performance'? What does it mean for you to share information in this context?

VGPerformance. For me, personally, it is a performance, even if it's an academic talk that involves the public in one way or another.

As for lecture performances, these do allow for certain things. You can really play around with the potential of this form because it's flexible but also very structured when you need it to be. I'd say it allows for speaking in many voices while inhabiting a story, or within a chosen narrative, and so much more in-between. These forms of agency are more like a script to me, and writing and developing them as you go along enacts a kind of rhythm.

ICLike actors in a workshop or rehearsing a play?

VGYes, there are some similarities. There is a certain crafting of language, of speech, and of thinking about its potentialities from the very beginning rather than closing it down in a contained, sealed form. It's exchangeable.

By this I mean that the potential even exists for someone else to do my talk instead of me, like an understudy in a play who is no longer only bound within the framework of rehearsal, quite literally.

ICThat makes sense. Even if the audience doesn't know it's a performance, what does register is that they're in a different set of circumstances than what they're used to.

Since we're on the topic of approaches used to activate art for an audience, you kept mentioning the idea of 'drifting' during your Asia Art Archive talk. What does that mean to you?

VGThis is tricky to describe in a few words, and I'm unsure about wanting it to be written down necessarily, but a drift is a liminal register. We live in geographies of drift. Drift has this quality of something shifting, of never becoming centralised or totally perceptible. Instead it kind of moves away, or has some strange dynamic in the way it exists. I can relate drifting to the book, Cloud Chamber, which was produced on the basis of The Guests 做东 at the Biennale. This was intended to be spawned from the future folk tale but in the end it became something very different. As a book, Cloud Chamber is itself a drift and moved away entirely from my original intentions for it as part of the work—thus, it transformed the work itself having emerged from and continuing to produce, a strange and convoluted temporality.

ICI like the idea of the 'future folk tale'; it is similar to the lecture performance because it has some sense of a standardised format. In this case, that is because the 'folk tale' is a recognised literary form but invokes a different register or tone, if you will, both textually and visually.

VGYes! I love that.

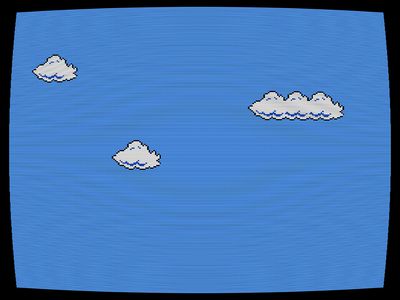

ICWhat about digital formats or what could be described as your occupation of the 'cloud realm'? Besides your book, Cloud Chamber, in your Asia Art Archive discussion you projected Super Mario Clouds (2002) by Cory Arcangel—one of his early works that references older forms of gaming technology, and which exists among a history of 'cloud art' works.

VGI just try to get material where I can. Regarding Cory Arcangel's work, it was about the cloud image in that particular manifestation—no fuzz—and the image-game economy.

ICYour work is definitely grounded in some form of material reality even when you're referring to something outside of it. Because of this consistency, an element of the subjective remains; for example, you can still 'handle' the cloud through its physical manifestation such as with the poster you circulated during your talk, or imagine it in reference to your book.

VGThis is more unconscious though; so not deliberate. I try to work less on the computer anyway, these days, and hope to do so more in future. But in general my investment into the materialities of whatever source changes over time. External changes have a significant effect–like if we talk about currencies of our present, here and now.

Also as part of my Asia Art Archive residency, I conducted the 'New Year Intensive'. It was an experiment because I worked mostly with people coming from the performing arts for the first time: experts from theatre and choreography. You could say that they are all experts on 'time'; including dancers, card readers, gamblers, and visionaries of all sorts.

During the programme we worked on questioning the book as performance, the book as a character or actor, and printed matter as ritual and celebration. Our prompts were: How to turn a performance in an exhibition or other physical space into a book? In what way does the book or artist book perform? Is it already always choreography? Is there something like an infinite space of a book as a relation between performance, the choreographic, and print? Can we reverse the temporal dynamic of a private print process or invisible production and publication? Essentially, we were investigating how the various pathways and layers of composition, adjustments, and production stages of a book could become one enlarged temporality and remain like that.

ICGiven your ongoing interest in utilising fiction, but also that of others such as those who contributed to your artist book Cloud Chamber, how do you see your role in relation to the artist as author?

VGI'm not necessarily invested in examining that as a question or using it as some sort of strategy per se. But from my more academic position I have looked into the phenomenon of fictional collectives for quite some time now; about how these fictional collectives keep popping up and have spread enormously over the last couple of years in particular.

ICYou referred to The Atlas Group in your talk, but what collectives or fictional collectives are you thinking about?

VGThere are so many! If you look at any bigger exhibition or biennale being announced on e-flux and other promotional channels—by this I mean what art, information, or otherwise circulates among the more obvious, visible, and seemingly domineering art world—all you see is repetition: the same artists' names, and in this case collectives, keep popping up. Why all of these fictional collectives? These are certain phenomena, certain drives if you like, that fascinate me. Thinking about them, the collectives, is really the point.

ICThere are many reasons why people get together and feel the need to have a unified voice, but you're asking how and why these collaborative entities exist.

We already spoke about the ways in which artists find agency; one of them is through collectives or through the book. But another that you mentioned in your talk is what we're doing right here, right now: the 'conversation-interview', which you describe as 'a space of exchange of ideas and histories.' Could you speak more about how the interview functions specifically for you?

VGAs a kind of drift, but in a similar sense to how I spoke about the talk as a medium of time. The interview brings other things into play in terms of its dynamics. It's curious to visit someone's home or a certain spot chosen by the person you're speaking to, wherever really. I'm also quite attracted to having someone in their own environment when speaking to them. It's not just about the person and the thinking around the conversation but the actual conditions surrounding them, its particularities as a unique encounter including the specific demographics, spheres, inhabitations, desire lines at play and the like.

On a more theoretical level, at the moment I'm looking into the notion of what sociologist Paul Ricœur describes as 'linguistic hospitality'. So the question of un- or re-translation and the dynamics of hospitality come in quite a bit. Then regarding the place of Asia you've been talking about, my curiosity lies in the economies of mis- or un-translating, and how these can be used in a way that plots or creates new translation spheres rather than only aiming for a binary interpretation between one language and another. Because aren't we always constantly in translation? So, mistranslating or un-translating, and 'foreigning' oneself might be more apt in response to our present condition.

ICSometimes these instances are more productive because they bring up underlying issues that get to the heart of what may really need to be discussed or worked out. Curatorially, there is the opportunity to find and create new platforms for artists as their work continues to grow and change. These are questions that seem constant amidst new and shifting conditions in terms of spaces of exchange, production, and display, from printed matter to digital platforms.

VGThe 'dark spots' when talking about space, so to speak. But again it's as we've already mentioned and what I referenced throughout my talk. There is a relationship between the material and immaterial through the book object and its symbiotic counterpart in electronic formats. It's also a question about resources because with books, as you know, there is a real cost and you have to place them somewhere. What budget do you have and how do people get around that? How far do you want to become visible or invisible and maybe less productive? I'm hoping to become less productive, in the sense of producing less overall. Or rather: we need to invent new vocabularies for the making we do—the relations we form in the various societies and communities, and with the cosmos.

ICYou are certainly bringing up some productive queries that prod and move the dialogue along.

VGHence the clouds, drifts, and riffs.—[O]