Zac Langdon-Pole: Lines of Flight

Zac Langdon-Pole in his Berlin studio. Courtesy the artist.

Zac Langdon-Pole in his Berlin studio. Courtesy the artist.

Over the last few years, New Zealand-born Berlin-based artist Zac Langdon-Pole has cultivated a practice of elegant, if at times uncanny, elisions.

His recombinations of objects, words, and images—poetry, meteorite fragments, literary translations, furniture, photographs, mollusk shells—emphasise, with a fine-tuned lyricism, the fallibility and incompleteness of how we tell stories of the world around us. Among Langdon-Pole's many approaches, he often zeroes in on nomenclature as a prompt for his audiences to drift through etymological use and misuse; at other points he exposes the colonial provenance buried within certain objects and their functions.

Paradise Blueprint (2017) and Tomb(e) (2016/2018), are both iterations of work related to the so-called 'birds of paradise': a species native to the Pacific Islands of Papua New Guinea, which were once a form of currency between European explorers and indigenous Papuans. In this body of work, Langdon-Pole focuses on colonial exchange and its concomitant taxonomies, built on the fault-lines of misguided scientific apprehension.

His presentation of re-prepared taxidermised bird specimens with their legs removed, stems from the long-held belief by European naturalists during the 16th century that these specimens, which they received with their feet missing, must not have needed feet because they lived perpetually in flight in a paradisal realm, only falling to Earth when they died.

Guided by inscriptions of this misconception, which found its way into numerous 16th-century encyclopaedias, the artist collaborated with a taxidermist to remove the legs of already taxidermised birds of paradise—a nod to the Papuan tradition and an invocation not only of pathos but of the poetry in the old scientific misapprehension-turned-myth, which gave the bird its name.

For his fully funded research trip, awarded in 2018 at Art Basel's flagship fair in Switzerland and realised under the auspices of BMW's Art Journey prize, Langdon-Pole returned to the avian world for inspiration. This time he used the flight paths of migratory birds, in part, as an itinerary for a trip through Western Europe from London to the Netherlands and France, through the Pacific Islands of Samoa, Hawai'i, and the Marshall Islands before its conclusion in Aotearoa New Zealand—the artist's country of birth. During his five-month tour of roughly 20 stopovers, Langdon-Pole worked closely with key interlocutors—scholars, artists, and sailors—at each stage of the trip to research places and their histories, using writing and photography to document many of these encounters. Central to his research was the artist's interest in celestial mapping as a kind of 'ground zero of meaning-making and storytelling' across civilisations and millennia.

The trip synthesises several years' worth of work and research by Langdon-Pole on movement, migration, and travel. Early in his career, for his graduation exhibition at Frankfurt's Städelschule, he facilitated for his then-professor, artist Willem de Rooij, a trip to New Zealand to take a single photograph at a specified location, while the artist himself remained in Frankfurt. The destination: a part of the Coromandel Peninsula known as Cooks Beach located on the east coast of the North Island where the artist and his family have regularly spent their holidays. The site is also where, on 15 November 1769, the eponymous arch-colonist Captain James Cook observed the transit of Mercury and raised the British flag in the name of King George III. The place is now called Cooks Beach and the surrounding area Mercury Bay, thus eclipsing the Māori designation, Te Whanganui-o-Hei (The Great Bay of Hei), after the Māori Chief Hei, who arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand on Te Arawa waka more than 500 years prior to Cook, and whose descendants form the iwi (tribe) Ngati Hei, local to the area.

The photograph taken by de Rooij is of a tree-lined river captured at a point where it connects to the Pacific Ocean. Langdon-Pole has re-printed and exhibited this same image several times, with each iteration being given a unique title and having corresponding material surreptitiously mounted to the verso of the photograph's frame, an activity the artist says he will continue by himself and in collaboration with others indefinitely. In one we find the title motherland (2015), which features on its reverse a sculpture made of seashells by the artist's mother, housing a plastic figurine of the Virgin Mary; another, The Torture Garden (2016), quotes from the opening passages of Octave Mirbeau's 1889 anarchist novel; and yet another, end of history (2015), borrows from an attached article by writer and scholar Miri Davidson critiquing the motivations behind the then-Government's plan to change the New Zealand flag and reach 'full and final settlement' in all land disputes between the Crown and Māori.

What the artist refers to as acts of 'interpolation' are assemblages of found material pulled into at times unsettling and unexpected communion, bringing into focus the histories of their formation, circulation, and transformation. With the piece emic etic (2018), for example, he brings together a 19th-century cast iron 'calf weaner'—a device invented during the industrialisation of farming practices to separate calves from their mothers—with a pearl-encrusted tiara acquired by the artist from the Buckingham Palace Royal Collections gift shop. Or in the subtly ornamental series, 'Passport (Argonauta)' (2018), for which Langdon-Pole brought together nine paper nautilus shells, placed directly onto a wall in a line, each housing one of nine unique meteorite pieces collected from different sites across the planet. Carefully shaped, polished, and etched to cut back their surfaces, the meteorite fragments reveal their inner material structure: 'a window,' as the artist says 'onto ancient geological time, older than earth itself'.

Langdon-Pole's presentation at the 2019 edition of Art Basel Miami Beach, running from 5 to 8 December 2019, will involve the launch of his multi-authored monograph Constellations. In the new year, Michael Lett Gallery in Auckland will present his solo exhibition Interbeing (29 January–29 February 2020). In this conversation, Langdon-Pole elaborates on how addressing travel, migration, and displacement has allowed him to work with and respond to the continuing impact of imperialism and develop a practice of drawing connections across history and its varying orders of scale and magnitude.

TJMYour journey for the BMW Art Prize began with the migratory lines of flight of the white stork and the Arctic tern. What drew you to using these birds as guides for your project's itinerary?

ZLPThe idea for structuring the itinerary around the migratory flight paths of birds was a preliminary one, inspired in part by Jon Bywater's essay Interrupting Perpetual Flight (2009). It was devised for the proposal I'd submitted in the intervening time between being shortlisted and eventually awarded the prize. As it turned out, my travels didn't strictly follow both these birds but learning more about them did provide an expanded way of thinking through travel and migration. As a guiding principle, it was one that could sit both outside, and also at the intersection of, human experience.

As with the white stork, I'd been researching how a number of German natural history museums house several specimens called Pfeilstörche, which translates as 'arrow storks'. The name originates from the 19th-century account of a man in northern Germany who had shot down a white stork with his rifle and on closer inspection found that it had a wooden arrow pierced through its neck. The arrow itself had originated from Central Africa, believed to be from a Congolese tribesman, and somehow the bird had survived its return migration north alive with the arrow still embedded in its body. Until that moment, European naturalists didn't have a scientifically robust explanation as to why storks disappeared or where they went for half of the year.

The second line of flight was that of the Arctic tern, which migrates biannually between Antarctica and the northern Arctic. This is the longest migration of any animal on the planet. Over a lifetime, a single Arctic tern can travel the equivalent of three round trips to the moon. Arctic terns, among other birds, were used by Polynesian seafaring navigators as guides between the islands.

I was drawn to these lines of flight not only because of their analogical potential in understanding migration on a 'global north to south' axis, but also as a way of de-centring human perspective and opening it up to the flows and interdependencies of the natural world, of which we are an inextricable part.

TJMWhere did you stop during this journey and what were some of the observations you made along the way?

ZLPThe trip unfolded in two stages. The first was within Western Europe from early December 2018 to early January 2019. It began in London, where I visited the British Museum, the Royal Observatory, and the National Maritime Museum to research celestial mapping, in particular how the Southern Hemisphere's skies have been mapped and imagined from European perspectives. At the time, the Royal Academy was also hosting Oceania—one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of art and culture from the Pacific region to be presented in Europe to date.

I then went on to Amsterdam and Dordrecht, where the research on celestial maps continued while I also looked at Dutch Golden Age representations of birds, in particular Abraham Busschop's trompe-l'œil painting, Ceiling Piece with Birds (1708). I then travelled to Paris and south to Lascaux, where, on the walls of 20,000-year-old caves, there are paintings of what are believed to be the earliest depictions of stars.

The second stage of the journey, from January to April 2019, involved travels across the Pacific Islands. It began in Hawai'i, where I visited Mauna Kea on the Island of Hawai'i and the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Mauna Kea is a phenomenal place, by far the highest mountain in the region. Its summit, which peaks high above the clouds, hosts a number of the world's largest and most sophisticated astronomical observatories whose presence is contentious given Mauna Kea's status as a sacred site to the Native Hawaiian people. Visiting this sacred site amplified my appreciation for the ongoing struggle of indigenous Hawaiians to protect Mauna Kea from the plans to build another enormous astronomical telescope at the expense of its environmental and cultural significance.

I then travelled to Majuro in the Marshall Islands and from there moved further south, to Apia, Samoa, where—among other destinations—I was travelling with Samoan-New Zealand artist-composer Michael Lee. The journey concluded in Aotearoa New Zealand where I was able to consolidate some of the research accrued over the preceding months.

TJMYou've mentioned previously not only the immediate effect of the climate crisis but the ongoing impact of imperialism and colonisation present in many of the places you visited. You spent ten days in Majuro, in the Marshall Islands, which is part of an archipelago of islands that includes Bikini Atoll, where the United States in the 1950s detonated multiple nuclear devices to ongoing disastrous effect. What came out of your time there and the encounters you had with local interlocutors about these islands?

ZLPIn travelling to Majuro, one person who was particularly inspiring to meet was Alson Kelen, the director and co-founder of WAM, or Waan Aelõñ in Majel ('Canoes of the Marshall Islands'). WAM is a nongovernmental organisation that teaches students how to build, sail, and navigate canoes incorporating traditional methods, skills, and philosophy. Alson actually grew up on Bikini Atoll before he and his village were unjustly relocated to make way for the atomic weapons testing programme. With his time there being formative for him in later becoming one of the custodians of traditional 'wave-piloting' knowledge, he's a crucial link to his communities past. Of course, the Marshall Islands are some of the lowest lying lands on the planet. And being some of the most remote islands, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, it's not like there's much higher ground to flee to during a high tide or with the current and impending sea level rise. So there's a lot at stake for the ways in which he and his community are seeking to link their past, present, and future. It was humbling really, just to be there and listen. One of the things we discussed was how to act local and think global. In this regard, it was enlightening to learn how even the most specific skills or tasks can have multiple reaches, far beyond the task itself.

TJMAmong the ideas informing your recent research, 'averted vision' stands out as a device through which the studied obliqueness of your work might be framed. What's your understanding of this term and how has it informed the making of your book Constellations subsequent to this trip?

ZLP'Averted vision' is an astronomical observation method I learned about during a visit to the Mount John Observatory, at Lake Tekapo in New Zealand—another one of the destinations of the BMW Art Journey. It's a technique one employs when it's difficult to discern distant or faint stars through a telescope. With this method, instead of staring directly at an object, one looks slightly away to its periphery. Due to a blind spot at the centre of our eye's optic nerve, stars will appear significantly brighter when viewed at their edges. This method can mean the difference between an object—or, better yet, a subject—being visible or entirely invisible.

In the making of the book, which both documents my travels and provides a survey of work I've made over the past six years, averted vision served as a useful structuring device to set up relationships between numerous divergent threads. One section of the book is a kind of photographic essay that's composed of a selection of some of the thousands of images I took throughout my travels and research. Laid out non-chronologically in constellated double page spreads, the proximity of one image to another affectively 'averts' the readings of the one next to it, allowing for a sharper image to emerge at the interstice between them. You might find, for example, a photo of a Dutch 16th-century trompe-l'œil depiction of the Greek fable of the Bird in Borrowed Feathers, next to images documenting the deep geological history of the earth as an assemblage of innumerable collisions of meteorites. Or photographs documenting the encyclopedic systemisation of the natural world at Paris' Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, beside ones taken at the customs gate of the U.K. border. In all these instances, the concept of averted vision encouraged me to work through the knowledge that whatever's at the centre of our attention and whatever is at its periphery is always interdependent.

TJMYou've also worked with historical misapprehensions, particularly in scientific histories, like the story of the bird of paradise and how it got its name. Could you elaborate on some of these errors, misnomers, and misapprehensions and what it is that draws you to them?

ZLPI initially came across the birds of paradise through Bruce Bagemihl's book Biological Exuberance, a compendium of homosexual behaviour in the animal kingdom. But it was the name that really stood out to me. While they're now probably most popularly known for their astounding mating rituals, in digging a bit deeper into this name I found that its genesis was further freighted with compelling complexity. When European explorers first came to the South Pacific, a number of these 'bird skins' were traded with indigenous Papuans. Only, as part of a local preservation tradition, Papuans would remove the feet of the birds. Either unbeknownst to the Europeans or simply lost in translation, once a number of these specimens reached Europe, naturalists of the time sought an empirical reasoning for this missing part of their anatomy. They concluded that these birds mustn't need feet because they live perpetually in flight in a paradisal realm above the earth and only fall to our world once they die.

At the time, I was interested in how an event like this is analogous to what is now called 'fake news'. I was thinking that the divisions we deem between the historical and the contemporary might not be as decoupled as we think. As I was undertaking further research on these birds during a residency in Singapore, a Dutch friend of mine pointed out that to call another person a 'bird of paradise', is meant as a euphemism for cultural difference. Like, 'Oh, don't mind him acting—or looking—strange, he's just a bird of paradise'. In all this is really a hard-boiled exemplar of exoticism, and by the exotic I mean in the sense that Peter Mason defines it, as something that is never at home. To me, this story poignantly laid bare the ingredients required in processes of making 'the other'. As beautiful and wondrous as the projection of a bird from heaven living perpetually in flight is, it's also rooted in a kind of violence, a severance. That all these visions spawned from a gap, an amputated part of a body, as well as the amputation of that body from its environment, spoke volumes to me about the ways we've engaged with nature and culture and fissures we create between these two categories.

For the first pieces I made in relation to these birds, I worked with a taxidermist from a Museum in Wiesbaden to re-prepare an already taxidermied bird of paradise in accordance with how they were initially traded and had traversed between worlds. This meant transforming a bird from its animated action pose—as they are so often presented within natural history museums—to a restoration of it as no longer alive-looking with its legs removed. Iterations of these re-prepared birds have been presented varyingly in gallery exhibitions. As, for example, with the installation Tomb(e) (2016) at Michael Lett Gallery where the bird was installed, as if fallen, on the floor of a former bank vault in the gallery's basement. I then had the bank vault door sealed with a glass pane so visitors could only view the bird from this threshold.

TJMAs with other bodies of work, you've returned to the bird of paradise as subject matter a few times, but often with a different set of materials and a shift in emphasis, conceptually.

ZLPRight. For the piece Paradise Blueprint (2017), I used the bird legs themselves as the basis for a wallpaper. This was made by placing the disembodied legs directly on top of photo-sensitive paper to make cyanotype photograms of them. More commonly known as blueprints, cyanotypes were an economical way to reproduce engineering or architectural plans, which also have an antecedent in the 19th-century botanist Anna Atkins' documents of plant specimens. By employing this particular method, the amputated bird legs register their forms as ghostly white absences amidst the deep blue of the cyanotype background. This image was then transferred into a pattern where the legs rotate clockwise and anticlockwise in alternating rows across the strips of wallpaper. Most often, the wallpaper gets installed at scales that fully encompass rooms so the effect is dizzying, with the legs becoming like negative shapes in a blue sky, at once made visible and yet rendered absent, tumbling somewhere between falling and flight.

TJMAnd from great heights you've descended to the oceans to make work using seafaring organisms in the series 'Passport (Argonauta)'. In that work, you've paired delicate marine mollusks with meteorite fragments, collapsing dissonant timescales and material qualities. There's also a geopolitical thread to this work, along with intimations of travel on more than a single level as seen in the title. Could you tell us more about this work?

ZLPThe 'Passport (Argonauta)' series refers to one of the oldest thought experiments in Western metaphysics, which poses the progressive refurbishment of Theseus' ship—the Argos—as a question on the foundations of 'being' and 'identity'. This thought experiment asks: if the components of the ship Argo are progressively replaced over time, can it still be identified as the same ship? I first presented this suite of work at Art Basel Hong Kong in 2018. There, it consisted of nine unique meteorite fragments handcrafted to fill the apertures of delicate paper nautilus shells, made by the genus of octopuses known as argonauts. Each of the nine meteorite fragments is shaped, polished, and etched to reveal the age-old geological processes through which they have been formed.

Calling the works 'passports' was a kind of open-ended provocation. On the one hand, I was thinking about how a passport is literally these sheets of paper, bearing inscriptions, that effectively decides who can travel where. The fact that the world's geopolitical borders and our identities are contained by these fragile pieces of paper is kind of confounding. Selecting meteorites from land sites from different parts of the world was a latent way to probe what is a relatively recent human invention: nations and nationality and their imagined essence. On the other hand, to me at least, there's a more planetary dimension to these pieces: one that's premised by a strong sense of fragility.

TJMThere are several new series of sculptures that you've developed and presented in the publication. One of these, 'Cleave Study' (2019), exemplifies your approach to 'interpolation' as a device, like montage, which informs your sculptural sensibility. How do you define this term and how would you characterise its function in your work?

ZLPInterpolation is inserting something of a dissimilar nature into something else. 'What belongs where?' is a question that often underpins my work and operates on multiple levels within each project I undertake. Sometimes it is literally expressed by bringing together specific objects or texts that might not usually belong together. Other times it is a more systemic question, with the work addressing how classification systems underpin how we relate to the world.

The word 'cleave' in 'Cleave Study' (2019) conveys two contradictory meanings: first, 'to strongly adhere, cling or attach to'; second, 'to split apart, sever, or divide.' In each 'Cleave Study'—(i) and (ii)—a Xenophora shell is attached to one half of a split anatomical model of a human tongue. Xenophora are small gastropod sea snails that, throughout their life, collect the debris of their environment—smaller shells, rocks, bits of coral, sponge—and affix these fragments to the outside of their spiral shells.

The Greek word, 'phora' comes from 'phero', which means 'to carry'. Xenos' standard definition is 'stranger', but it can also signify conflicting meanings, from 'enemy' all the way to 'guest-friend'. The latter is a hallowed concept in the cultural mores of Greek hospitality. When combined, these two parts of Xenophora become 'bearing—or carrying—foreigners'. The poet and translator Lyn Hejinian writes that 'The host is no host until she has met her guest, the guest is no guest until she meets her host.'³

TJMIn your 'Punctatum' series of 2016–2017, which has a strong familial dimension to it, you've considered a more specific set of guest-host relations: those surrounding colonisation in your country of birth, Aotearoa New Zealand. Can you elaborate on the series and how it extends your ongoing concerns with movement, displacement, and travel?

ZLPThe 'Punctatum' series consists of wooden furniture items—a longcase clock, a music shelf, and a writing desk—that were shipped from my family home in Aotearoa New Zealand to be exhibited within Europe. These objects were all once infested with borer beetle larvae—a non-endemic pest introduced to the ecology of Aotearoa New Zealand as stowaways in chattels brought by European colonists to the South Pacific. When my parents wanted to get rid of these items due to their degradation, I was fascinated by how even the tiniest hole in a piece of wood could be a lens through which to perceive and document the transformation of an entire landscape. So, following a kind of repatriation of these objects—time travelling from where they came—I then capped these tunnels with gold. While the method might echo the Japanese technique of kintsukuroi, or 'golden repair', which treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise, it could equally allude to the illuminated manuscripts of Christian scribes, who embellished words and letters with gold leaf to give them material value and thus ensure the preservation of their ideologies. On the one hand, the use of gold here quite simply makes the micro histories of these objects and the macro histories within which they've travelled visible, while on the other, it is really quite perverse.

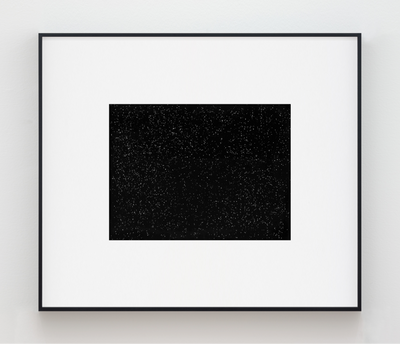

TJMCan you tell me a bit about these new night sky pictures that will be presented at Art Basel Miami Beach and in your upcoming solo exhibition, Interbeing, at Michael Lett Gallery from 29 January 2020? What's behind the title of the latter exhibition?

ZLPThis is an ongoing body of work that's steadily been accumulating over the past year and a half. Throughout my travels, I've been collecting small samples of sand from particular locations—think of the amount that might end up in your pockets after swimming at the beach. I've then made photograms of these, with each specific sand sample being poured evenly, by chance, over a light sensitive sheet of photographic paper. At first glance they resemble starry night sky pictures, but up close they reveal the ghostly minutiae and particularities of each grain.

Every photogram is titled according to the time and place that the sample was collected. In this sense, these works carry a torch for On Kawara and his 'Date Paintings' series (1966–2014), only yawed toward more speculative futures. Sand is of course a material endlessly freighted with associations—from being an analogy for time, as with an hourglass, to the infinite, as with Jorge Luis Borges' short story, The Book of Sand (1975). A more implicit context for the sand of these works is as documents of sites threatened by the prevailing forces of climate breakdown: the erosion and submersion of shorelines and the desertification of landscapes. So there's an acute twist to the aphorism 'as above, so below' involved in these works.

The exhibition title Interbeing derives from a term I first heard being discussed in relation to Richard Power's recent novel The Overstory. It's a term coined by the monk Thích Nhất Hạnh used to describe overarching tenets of Buddhism. The analogy for interbeing is 'to see a cloud in a piece of paper': the idea being that paper is made from trees, trees create clouds, and clouds feed trees, which make paper. —[O]