Zheng Bo: How to Live on Planet Earth

Zheng Bo. Courtesy the artist.

Zheng Bo. Courtesy the artist.

Hong Kong-based artist Zheng Bo's social, ecological, and community-engaged art practice has, in recent years, focused on moving beyond a human-centred perspective to an all-inclusive, multi-species approach. He takes up marginalised plants and communities of people as subjects in his large-scale interventions, which reintroduce wildness into institutional and abandoned spaces.

Plants Living in Shanghai (2013), for example, was an intervention Zheng realised at an abandoned Shanghai cement factory as part of the 2013 West Bund Architecture and Contemporary Art Biennale, for which he preserved the site for a period of time before its intended transformation into a bustling public plaza.

Zheng introduced more local plant species to the site, turning it into a community botanical garden, and to further contextualise the project, collaborated with local scholars specialised in ecology, literature, Chinese medicine, and architecture to organise an eight-week online course on MOOC with on-site activities taking place every Sunday.

This served as a way to investigate the past and activate present-day social and environmental issues in Shanghai through its plants.

Zheng has witnessed first-hand the dramatic changes in China. Born in Beijing in 1974, he grew up observing how the country became more and more affluent (in parts), whilst facing increasingly complex social, ecological, and environmental issues.

This return to close encounters with nature and other non-humans for Zheng is an urgent call to expand notions of human communities and publics, and 'think about interspecies communities and interspecies publics.' Nature becomes an expanded field offering a site for both radical thinking and experimentation for a future of equality for all.

Plants Living in Shanghai was a precursor to later works with weeds and plants, including Weed Party (2015–ongoing), an ongoing project exploring the relationship between plants and the political history of China, with its third iteration recently shown at Parco Arte Vivente (PAV) in Turin (Weed Party III, 4 November 2018–24 February 2019), after two weed garden installations were made for the interior spaces of Leo Xu Projects, Shanghai in 2015 (18 July–23 August 2015), and ferns introduced to TheCube Project Space, Taipei in 2016 (3 September–13 November 2016).

More recently, the artist's video installation series 'Pteridophilia' (2016–ongoing) has been shown at Manifesta 12 in Palermo (16 June–4 November 2018) and the 11th Taipei Biennial (17 November 2018–10 March 2019), and will also be included in the group show Garden of Earthly Delights at Gropius Bau, Berlin (26 July–1 December 2019).

The video posits the potential of eco-queer theories as a tool for connecting 'queer plants and queer people', and shows intimate encounters between plants and young men in a forest in Taiwan. In one part of the work, a man makes love to a bird's nest fern (Asplenium nidus), which he then eats, thus complicating the 'natural' habit of eating plants through the enactment of the tender yet 'unnatural' act of making love to them.

The video ends with local BDSM practitioners expanding their practice with three fern species—green penny fern (Lemmaphyllum microphyllum), flying spider-monkey tree fern (Cyathea spinulosa), and elephant fern (Angiopteris palmiformis).1

Blurring relations between ecology and human sexuality, the work reflects on a central critique of the eco-queer movement: that it is still a projection of human needs onto nature, which still cannot object to what is done to it.

For his forthcoming solo exhibition, Dao is in Weeds at Kyoto City University of Arts Art Gallery (1 June–15 July 2019), Zheng probes the dramatic changes that have occurred in the Suujin area of Kyoto leading to population decline in the working-class neighbourhood, while proposing future ecological solutions for the area as KCUA moves in as a catalyst for change.

As we move towards a period that theorists—and architect Liam Young—describe as the 'Post-Anthropocene', where technology and artificial intelligence are increasingly capable of computing, conditioning, and constructing our world, Zheng's works use weeds and plants to draw attention to the overlooked and the forgotten, whilst highlighting the power of marginalised people, plants, and other non-human forms to overcome imposed structures, and in turn, offer new models for reconnecting to the planet.

In this conversation, Zheng discusses the limitations of a Western-centric Anthropocene model, socially engaged art in China, multispecies interaction, along with equality conscious and eco-queer futures.

JDYour practice in recent years explores the relationship between plants, society, and politics. What specific urgencies led you to this focus?

ZBIn 2012, I moved to Hangzhou in Eastern China from Beijing to teach at the China Academy of Art. The city is very green, and the entrance to the academy is lined with large and beautiful plane trees.

I found myself in this green city famous for its West Lake and tea production, which is in contrast to what I knew growing up in Beijing—a city defined by its human politics.

This experience led me to a realisation of moving beyond politics and connecting more to the environment, and was a prequel to a project that I was invited to do at the cement factory in Shanghai called Plants Living in Shanghai (2013).

On my initial site visit to the factory in Shanghai, I was particularly amazed by the weeds that had been able to grow in the absence of human activity as the factory had since been moved out of the city.

I've spent the last few years learning how to live on the planet to see things as they really are and spend time with plants.

This absence of human intervention for a few years meant that the plants went wild and this was such a beautiful sight. The district government's plan was to transform the industrial site into a plaza for concerts. I decided to work with the weeds on site to try and keep them there a little longer.

This is how I began to work with weeds, but for a while, I didn't quite know why. After a few years, I realised that I was fascinated by marginality. I also began to notice similarities between marginal plants and marginal people—migrant workers, queer persons, and so on. For example, migrant workers in Beijing live on the peripheries of the city.

When gentrification happens, they get kicked out as well, which is kind of similar to the situation with weeds in urban environments. The intersection of nature and the city, and politics and marginalisation led to this interest in weeds. I work with plants as a medium for both learning and experimentation.

JDPropaganda Botanica (2015–ongoing) repurposes Marxist slogans by using plants to expand notions of 'equality', 'workers-rights', and 'socialism', while the eco-queer underpinnings of 'Pteridophilia' present new ways of thinking about male bodies in the natural environment alongside negating what intimacy means today in a disconnected world.

Beyond the human, you present engagements with nature as a non-judgmental and radical space. Do you view self-awareness and collaborating with nature as essential to creating future interconnectedness with each other and the non-human liveness around us?

ZBRecently on Instagram, I began posting images of my surroundings and for a while used the hashtag #returntoearth, because I feel most of us are not really living on earth anymore.

People talk about living in virtual reality and most of us are, in a sense, already doing this in our day-to-day lives. But even beyond virtual or digital simulation, most of us are not paying much attention to anything outside of human construction. We don't see plants, animals, insects, and we also don't think about or see the natural landscape.

Like I said previously, I've spent the last few years learning how to live on the planet to see things as they really are and spend time with plants.

I often think that my projects would look ridiculous to people living a hundred years ago, as they were not so cut off from nature. In the past, you didn't need to go to a museum to reconnect with weeds, and this is true for people living outside of modernity, who are more connected with other species.

JDArts and cultural institutions seem bound to the capitalist, neoliberalist, and neocolonialist system, more so than ever. How do the themes of 'revolution' and 'radicality' in your practice engage with the institutional frameworks that you often show in, and which some of your work directly contests?

ZBThe way I work with plants within an institutional framework is very 'weedy', by which I mean opportunistic. For example, with the film series, 'Pteridophilia', the first part of the film was made during a residency I undertook at TheCube Project Space in Taiwan in 2016, which involved engaging with the community nearby. This film and subsequent additions can now easily and readily tour.

For more site-specific and community-focused projects, these are contextually framed and ephemeral. When 'Pteridophilia' was shown at Manifesta 12 in Palermo, it wasn't made directly in response to the context of the biennial, unlike some other artists who were exhibited. I am not taking a radical approach and making a strong stance stating that I only work with communities, so this doesn't affect how I work with institutions.

I do however prefer to work with communities and with site-specificity even though I work between filmmaking, making slogans, research, and teaching. I don't see myself as being fixed to how I work, and I get joy in this almost 'weed-like', dispersive approach to the way my practice has grown.

JDAlongside making art, you taught at the China Academy of Art from 2010 to 2013, and currently teach at City University of Hong Kong, where you created the course Discovering Socially Engaged Art in Contemporary China. You have also recently established the digital archive seachina.net for the preservation of Chinese socially engaged art, supported by Cass Sculpture Foundation, The Space, and the British Council.

Such endeavours contribute to mapping the landscape of socially engaged artistic practice in China and furthering the discourse from a Western-centric view. What urgencies led you to teaching, and how does this relate to the establishment of seachina.net?

ZBDuring my MFA at the Chinese University of Hong Kong between 2003 and 2005, I began to develop projects dealing with social issues and minorities. At the time, no one was speaking about socially engaged art in this part of the world; my professors and I didn't know how to speak about these projects.

I came across a publication by Grant Kester called Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (2004), which I read, and that led to an awareness of the discourse on socially engaged art that I previously did not know.

I then decided to commence a PhD exploring socially engaged art in China after writing to Kester, who recommended I apply to the University of Rochester, where he studied for his doctorate, and where I received my PhD in Visual and Cultural Studies in 2012.

This led to me to return to China, where I began to teach socially engaged art, but I realised that, while my students were able to find information on foreign artists in this area, there was little on Chinese artists working in this socially engaged way.

The course at City University of Hong Kong and the digital archive were both born out of a necessity to change this lack through teaching, and it has since developed into an online course to further this area of study in China.

The archive also fills in gaps in the study of this form of practice, and gives a platform to artists whose work might otherwise remain unknown. It is hard for students here to find materials about Chinese art and our generation is responsible for making this change to create their own movements and discourses.

JDWhat does a future model for being look like to you? Can you also speak about specific artworks and themes you will be exploring for your forthcoming solo exhibition Dao is in Weeds at Kyoto City University of Arts Art Gallery (KCUA)?

ZBDao is in Weeds at KCUA deals with some of these ideas. KCUA will move from its former rural setting of Nishikyō-ku to the urban area of Suujin, which is populated with butchers, leather workers, and garden labourers; people described in Japanese as Burakumin, which translates to English as 'untouchable,' and encompasses lower-class workers.

The city government made the decision to move the university as the area's population decreased due to a decline in industry, and the area never really boomed because of the stigma towards the people who live there, even though it is five minutes from Kyoto station. The area has lots of empty plots of land, and half of the population is over 65.

I don't see myself as being fixed to how I work, and I get joy in this almost 'weed-like', dispersive approach to the way my practice has grown.

In recent times, the government tried to diversify the population of Suujin by creating public housing, which succeeded but didn't create a ripple effect. KCUA has already done previous projects in the area with artists and during my site visit in January, I met with architects designing the new university, a local activist, and an anthropologist, whom I will collaborate with to lead a workshop in late May to think about the ecological future of this area.

The history of the area is also interesting. In 1922, The National Levelers Association (全国水平社, Zenkoku Suiheisha) was founded here, and they published a manifesto that same year calling for equality all over Japan.

My proposal is that participants collectively update this manifesto for the next 100 years to move beyond the human and nation-state to the planetary and to all beings.

I strongly believe that we need to move towards this direction of inclusivity and equality for all humans and non-humans. The project will also consider ways to repopulate the neighbourhood without creating more buildings and expand capital value.

I really hope that this workshop will contribute to the future of the situation in Suujin. Inspired by Daoist interspecies thinking, I want to move this workshop and exhibition to really consider multispecies and eco-equality. A lot of people talk about rights of other species or rights of nature, but maybe because I grew up at the end of the socialist period in China, I feel more strongly about equality than rights.

JDYou graduated with a BA in Computer Science and Fine Arts from Amherst College in 1999: does this background relate to the way you engage with—and conceptualise a relationship to—nature in your work?

ZBMy studies in computer science actually made me realise how primitive digital technologies are. Recently, through my conversations with ecologist David Baker as part of my residency at Asia Art Archive, I learned that when it comes to storing information, DNA is so much more efficient than hard drives.

Like Eileen Crist, author of Abundant Earth (2019), I believe technologies cannot solve our ecological meltdown. It's only through transforming our worldview and scaling down consumption that we can possibly overcome this unprecedented ecological crisis.

JDFinally, you are also participating in the group show at Gropius Bau, Garden of Earthly Delights, which explores 'the motif of the garden as a metaphor for the state of the world and as a poetic expression to explore the complexities of our increasingly precarious world.' What will you be showing and how do you feel the work relates to the theme of the exhibition?

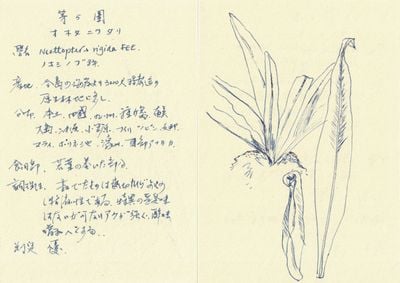

ZBFor Gropius Bau's group exhibition Garden of Earthly Delights, I will show 'Pteridophilia' along with Survival Manual II (2016), which is a hand copy of Taiwan's Wild Edible Plants published in 1945, in which Japanese colonialists suddenly realised the importance of ferns in Taiwan's flora when faced with the dire situation of survival.

The invitation to participate came as a result of curator Stephanie Rosenthal seeing 'Pteridophilia' at Manifesta 12 and wanting to further contextualise the piece through this exhibition, where the garden is used as a metaphor to bring together a varied group of artists in different global situations who are all concerned with the social, political, and ecological as this relates to their specific contexts.

In the conversations I have with young artists and my students, I feel like we really ought to be thinking about how we should live on planet earth as opposed to just focusing on what kind of art we make.—[O]