Zoe Butt on the Challenges and Rewards of Curating

Zoe Butt. Courtesy Zoe Butt.

Zoe Butt. Courtesy Zoe Butt.

Zoe Butt is the artistic director of The Factory Contemporary Arts Centre in Ho Chi Minh City, the first purpose-built space for contemporary art in Vietnam. Founded in March 2016, the Centre was designed by HTAP Architects in an old steel warehouse, with cargo shipping containers added to its structure. Initiated as a social enterprise multi-space, Butt joined The Factory in February 2017 after having worked as the executive director and curator at the independent artist-run space Sàn Art, also based in Ho Chi Minh City, where she developed projects such as Conscious Realities, an initiative that ran from 2013 to 2016 that saw thinkers, writers, and cross-disciplinary culture workers invited to partake in lectures, workshops, and a residency programme focused on shared histories of the Global South.

A few of Butt's key projects at The Factory include Poetic Amnesia, a solo show by Phan Thảo Nguyên (15 April–2 June 2017); Empty Forest, a solo show by Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn (9 December 2017–7 February 2018), and Spirit of Friendship, a group exhibition showcasing the history of artist groups and the development of experimental artistic languages across Vietnam since 1975 (29 September–26 November 2017).

In 2019, Butt was one of the three curators—alongside Omar Kholeif and Claire Tancons—of the Sharjah Biennial 14 (SB14) (7 March–10 June 2019), which presented three distinct curatorial perspectives encompassed under the title Leaving the Echo Chamber. Spread across the Sharjah Art Museum, Calligraphy Square, Al Hamriyah Studios, and Al Mureijah Art Spaces, Butt's exhibition, Journey Beyond the Arrow, was an effort to show the interconnection of the Global South. By introducing artists like Khadim Ali, Gudskul, Neo Muyanga, and Ampannee Satoh to broader audiences, Zoe Butt provided one of the few occasions where the context of the Global South is presented in such a comprehensive manner, in dialogue with other artistic perspectives and curatorial visions, while combining Western and performative aspects within the platform of a geopolitically key biennial, enabling further inquiry and conversation.

Drawing inspiration from historical circumstances of the Southeast Asian region in combination with local contemporary developments in cultural and artistic practices, Butt considers what it means to be brought up in and to navigate inter-colonially dense contexts, along with all the benefits and challenges this entails, attempting to untangle the complexities behind such sociocultural equations. From her institutional post with the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) in Australia, to working with the commercial gallery Long March Space in China and her voluntary post with Sàn Art, Butt discusses her trajectory to SB14 in this conversation. Reflecting on the challenges and revelations of curating multiple institutions tackling different censorship issues, she considers the complexities, awards, and challenges of her work.

MNTo start, could you talk about the key projects that have shaped your curatorial practice thus far?

ZBThe periods that have impacted my practice the most include the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art at the Queensland Art Gallery, where I worked from 2001 to 2007; Long March Space in China from 2007 to 2009, and Conscious Realities, a project I developed between 2012 and 2016 at Sàn Art. These three projects have shaped my ethical principles and my passion for interconnected histories, which has given me significant space and capacity to experiment with the kind of art I most want to support. My time with APT was groundwork for me as a young curator, where I questioned what it means to take production from undernourished contexts and communities across the Asia Pacific region and to bring it into Australia's highly interpretive and well-serviced infrastructure. It also taught me a lot about the differences in cultural thinking, the role of language in defining production once it has entered the museum environment, and curatorial responsibility. I left the museum world because I felt its exhibition structures were ignoring a whole set of responsibilities that were inherent to thinking about what it means to curate.

In 2006 I took up two positions—one in China and one in Vietnam, which I realised was not sustainable after going back and forth between the two places for three years. One moment that still resonates with me, though, is a discussion I had with Long March Space founder Lu Jie, who I was working with on projects that were engaging the differences between rural, urban folk, and mainstream ways of thinking about art, and what it means to have a comparative memory or comparative approach to making, writing, or speaking about culture. He taught me to respect and examine the local in a way that I hadn't before. Growing up in Australia, my sense of community was really confused. Being half Chinese and half British and growing up in a town where very few people were not white, I didn't really understand my place in the world. China was my turning point—I realised that where I commit myself to being a curator and writer goes beyond my cultural and genetic make-up. It is about community and understanding local nuances.

Consequently, I decided to stay in Vietnam, where Conscious Realities at Sàn Art, a public programme of lectures and workshops initially organised in collaboration with Vietnam National University in Hanoi and the University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Saigon, was an important experience. This was a series of guest lectures with invited scholars from across the Global South whose contexts had similarly undergone colonial rubrics. The project responded to the question of what it means to be conscious—that if we are conscious human beings, we should have a full canvas of the past, and should be allowed to interrogate what we think. However, in Vietnam and much of the world, it is not allowed. So how do we move between these landscapes? How do we share experiences as colonial subjects, to better understand our own histories from different viewpoints?

This decision to work on the Global South eventuated from a frustration of funding streams dictating content here in Vietnam, as so much money from Germany, France, the U.S., Britain, and Japan was being used to create programming oriented around those countries' own cultural histories. There was all this cultural memory that I felt was being drastically overlooked. Workshops and lectures were staged at Vietnam National University, the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, and Hoa Sen University where certain knowledges were unpacked relevant to each guest. Participants included cultural theorists and scholars like Ravi Sundaram from New Delhi, Prasenjit Duara from Singapore, and Ntone Edjabe from South Africa—all coming with different references, terminologies, and experiences to provoke and compare an understanding of our 21st-century selves from Vietnam. A textbook was created as a result of this programme, with all the texts translated into Vietnamese.

In addition to the workshops and lectures, Conscious Realities also included a residency programme run by Sàn Art called Prod/Ponder, where visiting artists from the South would stay for a month, working with local artist-residents who were guests of Sàn Art's main artist residency, Sàn Art Laboratory, which targeted Southeast Asian artists who would stay for six months in the same place the Conscious Realities guests were staying, which created incredible opportunities for discourse and collaboration. There were exhibitions and presentations taking place that shared context, intent, and method, and it was generally a very dynamic time to realise the sheer amount of work that needs to be done in terms of unpacking colonial subjects and subjective colonial experience.

MNIt's interesting that public programmes have been pivotal in the development of your curatorial practice—curators usually point to important exhibitions as milestones in their work.

ZBDue to ministry approvals, there have been many unrealised exhibitions. This lack of access to visibility led me to invest time into building residency programmes for artists and thinkers. Very interesting artwork was produced as a result of these—most of which it is sadly not possible to show in Vietnam. My ideas for SB14 were formed as a consequence of that work. For example, Kidlat Tahimik, Khadim Ali, Jompet Kuswidananto, and Adriana Bustos, who were in Journey Beyond the Arrow, were also part of Conscious Realities.

MNHow does your work at The Factory compare to your previous projects?

ZBIt is a totally different experience. The Factory is a private institution—the first purpose-built space for contemporary art in Vietnam—with a number of events and shows to be realised each year and a public mandate to follow, but I am enjoying the change thus far. At Sàn Art, the focus was to cater to the interests of artists, whereas the goal at The Factory is to reach the general audience and promote a wider understanding of the validity of contemporary art within the community, which requires a completely different type of aesthetic thinking. I do miss the occasional impromptu art conversation that at Sàn Art could be easily turned into an event.

MNDo you think it is possible to create and integrate artist-based rather than audience-based programmes at The Factory?

ZBYes, that is the goal, but there are time limitations, because 'visible' programmes have priority over those that are 'invisible', whereas at Sàn Art we would freely focus on invisibility because it was the only thing we could do. Being visible means applying for license and official approval. Being invisible means working only within your networks and offline. In terms of the 'invisible' side at The Factory, we are developing some important educational programmes with the team by collaborating with different local and regional universities to train artists to be teachers. There seems to be a major lack of practice behind the teaching part, and as a consequence, many of the graduating artists are treating their 'practice' merely as a commercial outlet where they repeat successful modes and images without the understanding of what it really means to think within an art context. One programme we are really trying to get off the ground, in collaboration with the university, is creating curricula that takes the learning of art to the artist's studio.

Another programme we are working on is focused on cultivating writing and reading through learning fiction, and what it means to be thinking about art, which is another thing that is generally lacking in Southeast Asia. What is the role of critique and what does it mean to have an opinion? In much of this region, having your own opinion is prevented, rather than supported. How can we create safe spaces for independent thinking and be openly accepting of the differences we have with our opinions?

MNThis is a timely topic. American art historian and art critic James Elkins' ongoing 'book project', The Impending Single History of Art: North Atlantic Art History and Its Alternatives, which is being loaded progressively to his website[1], discusses the fact that, despite recent efforts to include the periphery in the art historical canon, Western theoretical discourse does not only continue to dominate throughout, but has also managed to render most interpretive methodology uniform, leaving no room for indigenous or regional philosophical thinking or approaches. How do you hope to develop the more educational aspects of your programming at The Factory?

ZBThe project with the university is looking at training artists to be teachers and engage an understanding of practice through talking, as there is not a lot of ease when it comes to writing. From my experience here, I have found that if you can develop talking, then writing follows.

It is important to understand that in Vietnam, there is not a lot of writing that exists on aesthetics. In Southeast Asia, it could be said that Indonesia and the Philippines are the most sophisticated in understanding their modern and contemporary aesthetic language, and there is a decent number of people you can quote who can challenge Western paradigms. Beyond that, it is really difficult indeed, which is why a lot of young people in Vietnam quote Western theorists. My concern has always been why they don't quote Indonesian or Filipino writers, but this is due to a lack of access to resources—there are few libraries in this region. It is important to recognise the lack of access, circulation, and leadership when it comes to education, and to acknowledge that teachers need to open up their resource pores.

We recognise the need for teachers to be artist-practitioners, since the basis of teaching must come from experience of practice. But most of these universities are now governed like businesses—they need to show measured output, which is why they want a partner with community spaces that afford opportunities to show their teachers' and students' work. This has been an interesting learning curve when considering how education is geared; it's about peak performance, indexes, and how to ensure these students find future employment. These are the concerns I am returning to after having finished SB14, for which it was such a treat to be able to work with artists on solid, visible projects with a publication, and build so many critical relationships in such a short time.

MNSB14 was composed of three shows, each curated by an individual curator. How was the overall concept for the Biennial conceived?

ZBThe concept was decided early on at a meeting in London, in an effort to align three different practices together, between people who didn't really know each other. We all agreed that Omar's title suggestion of Leaving the Echo Chamber, 'echoed' our three voices well. Claire's focus was on reprioritising the senses in an effort to experience the visual arts through a sense other than seeing, and Omar's was about the notion and perception of time through material and virtual culture. Mine stemmed from a desire to connect artistic research of colonial histories and empathic gestures of survival, which are often overlooked or disregarded.

During our first meeting, we all had somewhat particular geographies of passion in our work, but we all also ended up doing research in other areas relating to our focus. I was keen to further explore West Africa, due to its connections to the globalising south colonial histories I was looking into. Even though I was unable to revisit West Africa due to time restrictions, I am pleased that I was able to help artists travel to conduct research. For example, Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn from Vietnam travelled to Senegal, where he interviewed the descendants of French Senegalese soldiers and their Vietnamese wives for his four-channel video installation, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming; while Jompet Kuswidananto, from Indonesia, travelled to Ghana to unpack the presence of the 'Belanda Hitam' (Black Dutchmen) or royal colonial soldiers whose stories hail both Indonesia and Ghana in his immersive music performance and installation at Al Hamriyah, Keroncong Concordia. Both of these examples look at notions around intercolonial communities.

For me, this Biennial is about human movement. I wanted to work with stories that show how human movement can challenge political histories and cultural memories in ways that we don't hear about in our dominant echo chamber. An example is the normalisation of violence in militarised histories, like the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia and its little-discussed impact to that region's sense of geopolitical unity. Another example of a deeper history is the role of the Arab world in parts of Southeast Asia, as well as China's migratory movement south, following the collapse of the Ming dynasty. I wanted all of these histories of voluntary and involuntary mass movement to be present in the majority of the work.

Most of the artists I worked with were either refugees themselves or have directly witnessed such contexts, but the way they spin back their traumatic experience reveals marked resilience. I wanted to demonstrate that if we don't appreciate the value of human movement, we lack cultural introspection and innovation, and fail to understand the full capacity of the human mind, as human movement is as mental as it is physical. A lot of the artwork in the show reaffirmed my own commitment to curating, precisely because these works clearly render the role of artists and their movements—in research, ideas, and in the sharing of their practices—as the reason why art and culture is necessary in society today. Their stories tell us the relevance of ourselves elsewhere.

MNHow did the broader context of Sharjah affect your approach?

ZBSituating Sharjah within its geopolitical region and broader histories involved asking what the impact of this world and culture is on my geography. For instance, in one part of Journey Beyond the Arrow, I attempted to show how the Arab world has left an imprint on my region; how it arrived, conflated, or has become interwoven with debates of (neo) colonial influence, and how the Indian Ocean wrought trade and migration in the precolonial era. I found it fascinating that the U.A.E. local population is only about 20 percent Emirati, which, together with its traditional society's strict rules and belief system, reminded me of particular communities in Southeast Asia, like Mindanao in the Philippines. It also led me to consider how the U.A.E. and its Filipina overseas workforce recalls the Philippines' strategy to nationalise this workforce, and to remember that much of the Islamic community across the Malay Archipelago originally came from Yemen.

I was hoping that such connections might be visible to the local audiences of Sharjah, so that they might see a reflection of themselves in a different light, and understand that their community's cultural histories have a relevance to parts of the world they might not have thought about. It is very tough to form this kind of historical conversation in Southeast Asia. In that way, Journey Beyond the Arrow tried to offer a glance at different time periods, with much of the work revealing how history is repeating itself, and how a lot of precolonial memory still resonates with a lot of dilemmas not acknowledged by History.

The focus of my exhibition was about the movement of people, from Southeast Asia and beyond. It gave me the opportunity to re-consider how to look at my region by showing particular artistic views that engage with the cultural consciousness of the Afro-Arab world. It also forced me to re-examine what it means to be 'metis', or to think creole today—to not just assume that this identity is a product of inter-marriage between the colonial occupier and its occupied population, but also of inter-marriage between its colonial subjects.

MNHow was that reflected in your SB14 curatorial? Can you provide an example?

ZBThe basic premise of the show is an examination of what I call an artist's 'toolkit'. Journey Beyond the Arrow challenged our preoccupation with 'arriving', to focus instead on the context of departure, which, to me, is represented by the bow. The arrow is launched from a bow, but we don't spend much time thinking about that bow because we are constantly thinking of what occurs when that arrow lands. For me, the bow is the context of an artistic practice—it's the place and space from where the arrow has been let loose. For example, Tuấn lives and works in Vietnam, but his filmic arrow is aimed at the ghosts of Vietnam in Senegal through colonised descendants of the French Empire. Ahmad Fuad Osman's Enrique de Malacca Memorial Project highlights the life of Enrique of Malacca, the Malay slave of Ferdinand Magellan, whose ships encountered the entrepot of an Islamic cosmopolitanism in 15th-century Malacca in Spain's search for spice.

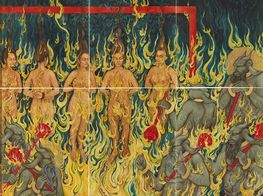

In the case of Khadim Ali, a Hazara refugee who now lives between Afghanistan and Australia, he continues to critique the international landscape of charity by demonstrating the Taliban exploitation of Rustam from the Shahnameh, as explored in his monumental mural from the series 'Flowers of Evil' outside Sharjah Art Museum. In his sound installation Urbicide (2019), Ali contrasts this terrorist ploy with the sound of religious extremist songs that populate Taliban-held areas of Kabul. It is the employment of tools such as ghosts, spices, mythical heroes, sound and so much more, that connects a lot of the work in the show. The Biennial focuses on the echo of the chamber as human ritual, tradition, language, memory, and cultural practice, whereby the idea of the flag, written journals, and all kinds of psychological and physical processes are identified as 'toolkits' of survival.

There were also two commissioned toolkits for SB14. The 31st Century Museum of Contemporary Spirit from Thailand, for instance, did a four-day intensive during the weeks leading to the Biennial, which involved the Sharjah publics. Participants were asked to bring an image or object that activated a memory that involved someone they didn't know. These objects and their owners then became part of the show. Their stories were subsequently placed inside an e-book that you can download from the Sharjah Art Foundation's website. These pages were also displayed on the wall of the exhibition in English and Arabic.

The other commission was Gudskul from Jakarta who offered an interactive toolkit, inviting members of the public in Sharjah to sit down in a choreographed space to exchange instructions of 'how to' knowledge, reversing the teacher-to-student relationship. Knowledges included how to cure a sprained ankle with traditional medicine, or fuel a car when you're out of gas. At the end of the session, each participant came out with a little book of 'how to' notes, which were collected and made into a book at the close of the Biennial. This interactive work took place across four different sites in Sharjah, including the city centre, along with Al Madam and Khor Fakkan.

MNWhat were the challenges you faced when working on the Biennial? Where did you have to compromise?

ZBAfter our first meeting in London with co-curators Claire Tancons and Omar Kholeif, we quickly realised that due to our other major work obligations, the opportunities to meet in a collaborative and consistent fashion required an administrative effort that would be unrealistic, so I feel there was a lost opportunity for a proper team collaboration. This could have been a bigger opportunity for me to learn as a curator, but in light of the situation, having three different shows was a necessary and productive compromise.

Also, the amount of history that is present inside Journey Beyond the Arrow was a challenge to facilitate due to its density and because it was coming from such a different part of the world than is usually attended by regular biennial-goers and Sharjah audiences, which made me worry, at times, as to whether it would be too overwhelming or feel too didactic. Therefore, I had to take care in making sure the exhibition text was informative, but not too literal, so that people would be captured by the mastery and allure of the works, and honour them with the appropriate time and contemplation.

Other challenges included the balancing of time and responsibilities across two major institutions within an unfamiliar context, in the case of Sharjah, and in the face of government restriction, in the case of Ho Chi Minh City.

MNSo you did not face censorship issues in the Middle East?

ZBSharjah was like a breath of fresh air for me in that regard. Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn and Phan Thảo Nguyên, for example, are sometimes very difficult to show in Vietnam due to the documentary material in their work, which is potentially considered historically sensitive. In other cases, Khadim Ali produced a lot of work in Kabul with women weavers: brilliant embroiderers, whose husbands would not allow their wives to continue working on the project because they were producing figurative visuals in the rugs that go against Islamic scripture.

MNWhat was the main lesson you took away from the experience?

ZBMany creative thinkers in my community come from contexts of violence and I often feel helpless with my work, questioning the relevance of the arts as too tenuous, at times pretentious and self-serving, compared to the world's real problems. Why am I losing sleep over an art exhibit when there are people dying and suffering? But writing and speaking about my Sharjah experience, I am again reminded that culture is one of the last grey zones of society. It is a space where we are allowed to contemplate the Other—a space of hopeful grace where we can come to an understanding and say: 'I don't understand what's in front of me right now and that's okay.'

I am grateful to the artists for making me stop and think and research. I have a whole other map in front of me, as a consequence of what these artists have shared, and I believe it is just the beginning. Because it isn't just about Southeast Asia for me, it's a much longer set of human equations that, for example, remind us of the connection between Yemen and Malaysia, and of figures like Enrique de Malacca, a slave who is believed to be the first to circumnavigate the globe—and not Ferdinand Magellan, as dominant history would account—who is today eulogised in near-religious ceremony in the Southern part of the Philippines. There is so much more to be done, and I am excited because I feel that this is just the beginning. —[O]

—