12th Bamako Encounters Explores Africa as a Planetary Concept

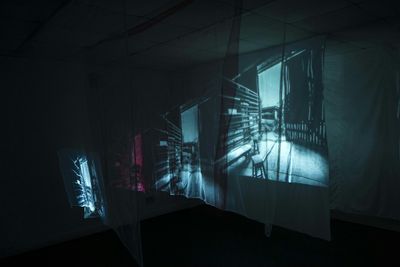

Christian Nyampeta, Sometimes It Was Beautiful (2017) (still). Courtesy the artist.

The twelfth edition of the Bamako Encounters Photography Biennial (30 November 2019–31 January 2020) is a varied lens-based inspection of the material and natural world, moving from postcolonial histories and imaginations to religion and the sacred, cycles of life and death, and transitory condition of places in-between. With works by 85 artists and collectives operating within Africa, its diaspora, and elsewhere, the show unites the global and local through the definition of Africa as 'a planetary concept' that relates to people of African origin 'spread over the world in Asia, Oceania, Europe, the Americas, the African continent.'

Organised by artistic director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung with co-curators Aziza Harmel, Astrid Sokona Lepoultier, and Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh, and artistic advisors Akinbode Akinbiyi, Seydou Camara, and scenographer Cheick Diallo, the exhibition title, Streams of Consciousness, outlines the curatorial inquiry: 'Can photography reveal the Streams of Consciousness that flow from and beyond the shores of the African continent?' This question unfolds across cultural landmarks, educational institutions, and private residences across Mali's capital, including Musée National du Mali, Mémorial Modibo Keita, Institut Français de Bamako, Galerie Medina, and Cinéma El Hilal.

Film contributions stand out, providing a change in pace to photography's static presence. Theo Eshetu's nine-minute film, Zar Possession (2018), presents a restaging of the ceremonial practice known as zar, an ancient ritual originating in Ethiopia that functions as a ground for liberation and invocation for women, now experienced in other parts of East and North Africa and the Middle East. Showing at the Musée National, the film opens with a black screen that intermittently flashes red and white before revealing a dimly lit room with a blood-red chair in the centre—red being a common feature in different variations of zar rituals as a colour that symbolises the mediation between the human and spirit worlds. An interlocking performance unfolds between a young woman robed in an off-white dress, an older woman chanting Arabic whose hair is concealed in a veil, and a man playing a flute, its high-pitched whistle billowing amid a medley of sitar-like instruments.

Throughout the exhibition, the line once separating artistic film from conventions of visual anthropology becomes increasingly blurred.

Reinstating the artist's longstanding concern for dismantling culture, perception, and the caverns of sacred being, Eshetu's film is well positioned within one of the Biennial's four chapters titled The Sudden Scampering In The Undergrowth: On Presence of the Invisible, the Remote, and other Ghostly Matters—a verse borrowed from a poem in Ghanaian writer Ama Ata Aidoo's play, The Dilemma of a Ghost. At one point a group of people grapple with a cow bound in red and black cloth, as part of a ceremonial slaughter, before a dark-skinned man with a white-powdered face cheers to the screen, smoke wafting from his pipe, as if to signal the ritual's end.

Expanding on artistic director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung's definition of photography, which asserts that the medium is not about what one sees but what it can conjure[1], the power of Zar Possession lies in its will to dominate the viewer. Alluding to carnal ties between humans, animals, bloodshed, water, and forces beyond mortal realms, the film feeds on the human need for spectacle.

Of course, Eshetu is not the first artist to draw on naked dark-skinned bodies yielding weapons in scenes where men taste knives bathed in blood. The artist plays up to the voyeur's senses and gains from the unaccountability of showing images that are nondescript yet feel deeply fetishistic, with the film's spectator receiving a carnival of sorts. Alas, people can be easily enticed by the fantasies of others and Streams of Consciousness offers a broad route to this state of wanderlust. Throughout the exhibition, the line once separating artistic film from conventions of visual anthropology becomes increasingly blurred.

In a hall located in the back courtyard of the girl's high school, Lycée Ba Aminata Diallo, Dicko Traoré's short film Djoliba, Fleuve Niger (2019) is presented on a black plasma screen affixed to a white pillar. The film focuses on the Djoliba, which is the Manding name for Africa's third longest river, the Niger River: an essential source of livelihood for more than one hundred million people in the West of the continent. Invoking the universe beyond mortal realms, Traoré summons the deities of the river to restore the ties that bind humans to water, with Malian dancer Fatoumata Bagayoko appearing possessed by the djinn, a spirit known for its ability to wield physical control over human bodies.

A split screen features throughout the film, with what appears to be the djinn visible on the right in the form of the rumbling river, its rupturing currents mirrored in Bagayoko's pulsating body on the left mirroring its temperament: a state of restlessness in the face of violent industrial invasion.

Situated in the same space is Other Side of the Creek (2019), a mesmerising film by Halima Haruna that examines Nigerian sociopolitics, environmental neglect, and natural resource mis/management within Africa's largest economy. Scenes show the artist practicing a ritual on grasslands within a bamboo cage, and nightscapes shot on the exterior of a petrochemical industrial site, signalling the enduring environmental pollution and loss experienced by communities in the Niger Delta where countless oil spills have decimated arable land and livelihoods. Establishing Haruna's concern for the preservation of Yoruba ancestor relations, the artist's sombre voiceover narrates the action, expressing a search for knowledge about the future from the elders that came before her.

There are a few artists in the Bamako Encounters Photography Biennial who integrate queer existences into their respective presentations. Pinned to the wall of a curved room in the Musée du District are black-and-white and colour images by Liz Johnson Artur: a series of photographs that are emblematic of the transient ties the artist forged throughout her journeys traversing continents and communities where queer and ethnic minorities collide in the U.K. and U.S.A. Youth appear in spaces of inclusion and communal jubilation, such as the annual U.K. Black Pride in London. As the only works in the space, their portraits take utter control of the room.

Within the Biennial's subtitled section, The Twig Shall Not Pierce Our Eyes: On the Possibility of Hope and the Future as Promise at the Palais de la Culture Amadou Hampaté BA, Dustin Thierry's large-scale prints focus on transnational queer ballroom culture, which entered the mainstream as a result of Pose, the cult American television series centring on gender-nonconforming ballroom culture in 1980s New York City. Intimate portraits immortalise the flamboyant and brazen in the backs of bars, urban dwellings in Paris, and other European cities: a material history of those who have chosen their own families after the rejection from those to whom they are related by blood.

Exhibited at the Musée du District is The Otolith Group's The Nucleus of the Great Union (2017): a film that blends historical archival imagery with contemporary digitised representations and interfaces in which the research process constitutes as the artwork. The work uncovers 1,500 images taken by African-American author Richard Wright during his journey travelling the Gold Coast on the Gulf of Guinea in the summer of 1953, moving in close quarters with political elites and experiencing unprecedented access to Ghanaian campaigning efforts for independents from British rule. Shorn of the writer's words, the images capture the apprehension of political transfer from the British Empire to the Gold Coast colony to Ghana, the post-colony.

Alongside these archival images is a screen display mirroring a MacBook desktop, with multiple open tabs and countless files in download mode, charting the arduous work it took to attain Wright's imagery from the special collections at Yale University, highlighting the widespread absorption of material histories by institutions beyond their borders. Another section of the film features iridescent coloured background displays and tracks Google Earth in use: a modern paradox when considered against the sober black-and-white photography that features in the film of President Nkrumah in the early days of his presidency in Ghana. Marked by idealist politics of post-independence Africa, Nkrumah's presidency instilled shared hope for redefinition: a stark divide from today's deep shifts towards conservatism.

With its overlapping and contrasting histories and spectres, Streams of Consciousness expands and challenges inherited tastes and perceptions: an epic curatorial approach that fits the landmark 25th anniversary of the Bamako Encounters Photography Biennial, founded in 1994. The mystified meaning of a stream of consciousness validates an undulating in subject matter, form, and messaging, not to mention the Biennial's multiple sub-themes, series, and segments, which at times prove difficult to decipher. With a headline argument noticeably lacking, the show sets itself apart from preceding editions, led by the late Bisi Silva and others, as a dense visualisation of visible and invisible trajectories, in which a central commentary remains obscured. —[O]

—

[1] Streams of Consciousness, Bamako Encounters Catalogue, (Archive Books / Editions Balan's, 2019), p. 32.