The 5th Aichi Triennale Is a Reminder to Keep Living

Watanabe Atsushi (I'm here project), The Moon Will Rise Again (2021). From the project The Day We Saw the Same Moon (2021). Photographs of the moon by I'm here project members: The Day We Saw the Same Moon, R16 studio (Kanagawa, Japan). Photo: Keisuke Ino.

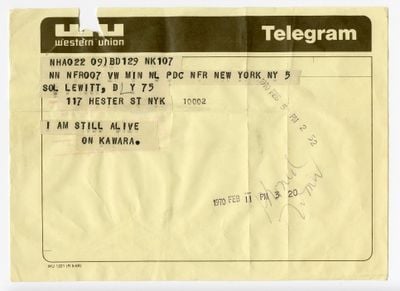

In 1969, the Aichi-born artist On Kawara began sending telegrams from his adopted home of New York to curators, collectors, and acquaintances across the world.

Each telegram expressed a simple message: 'I am still alive', a declaration of the artist's existence. On Kawara sent around 900 telegrams until 2000 and stayed alive for another 14 years, culminating in a life lived over 29,771 days, per his official biography.

As art historian Jung-Ah Woo writes, the 'trivial daily labour' On Kawara enacted could be seen as proof of the artist's survival: a contemplation on time, space, and history.1 These themes are extended in the fifth edition of the Aichi Triennale (30 July–10 October 2022), which takes its title from On Kawara's telegrams, STILL ALIVE.

Directed by Mami Kataoka, director of Mori Art Museum, works by 100 artists from 32 countries and regions, including Theaster Gates and Tuan Andrew Nguyen, are presented across the cities of Nagoya, Ichinomiya, and Tokoname, plus the town of Arimatsu, in Japan's Aichi prefecture.

At Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya, the show opens with 46 telegram papers from On Kawara's 'I Am Still Alive' series (1970–2000) displayed in glass cases like modern relics, alongside the names of sender and receiver, including collectors Dorothy and Herbert Vogel, writer Teresa O'Connor, and artist Sol LeWitt.

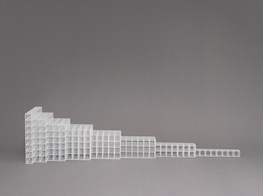

Nestled in the corner of the gallery space is On Kawara's 'One Million Years' series (1970–1998): a set of 20 leather binders, each 200 pages, divided into Past and Future. Ten are subtitled 'For all those who have lived and died' and include the years 998,031 B.C. to 1969 A.D. typed out. The other ten, subtitled 'For the last one', include the years 1981 A.D. to 1,001,980 A.D.

Despite conceiving of time on a cosmic scale, 'One Million Years' seems to reflect the tenets of the 'I Am Still Alive' telegram series. Both frame time through its subjective, multiple, and spatio-temporal variability. Across Aichi Arts Center, works expand these fractal ideas, with Pablo Dávila's Transference Harmonies (Armonías de transferencia) (2020) seeming to translate the intensity of 'One Million Years' into abstract images.

Made of around 9,000,000 digital pixels in white, black, and grey, seemingly infinite abstract patterns move on a monumental L.E.D. screen measuring 2.2 by 7.2 metres. They appear like a constellation of twinkling galaxies: an accumulation of temporalities recalling the cosmic expanse of time and space.

Dávila's A friendly reminder (2022), on the other side of the gallery, consists of three analogue tape recorders emitting a repeated two-second-long recording of stringed instruments and humming female vocals: a repetition recalling On Kawara's use of repeated acts to express life's profound monotony.

In the same venue, Jimmy Robert weaves On Kawara's spirit into the gestures composing Reprise (2010): three life-sized photographs, each picturing the artist making various ballet movements, positioned in three different sections of the gallery.

The first photograph, depicting the artist stretching his leg, is gently curled with a ribbon and placed on a stand on a wooden pedestal to one side. In the middle of the space, a long photograph held by the crack of a high table is draped like a stage curtain. At the end of the space, two reprints of the first image—one cut into puzzle pieces, and the other rolled up horizontally—are laid on a wooden pedestal on the ground.

Viewers can only see fragments of these images from any given position. This framing of each movement as both mutually exclusive and part of a larger composition extends to the Aichi Triennale's poetic engagement with a key question: What does it mean to stay alive in an era of constant crises, when the struggle to survive often trumps the ability to live?

With that in mind, artworks across venues activate a multi-layered conversation around what it might mean to live differently.

Taking up this challenge is another work at Aichi Arts Center by Aichi-born artist and architect, Shusaku Arakawa, known for residential works designed and built with Madeline Gins. Among them is Reversible Destiny Lofts—Mitaka (In Memory of Helen Keller), an apartment completed in 2005 in Mitaka, Tokyo: nine housing units primarily constructed using three shapes: the cube, the sphere, and the tube.

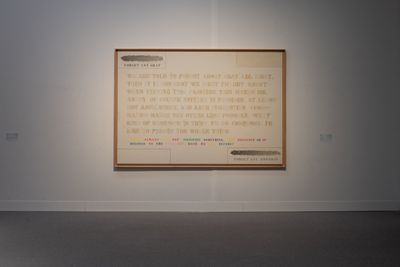

Arakawa's painting, PINK (1971–1972), depicts opposing propositions written on the upper left and lower-right side of a beige canvas: 'FORGET ANY GRAY' and 'FORGET ANY NON-GRAY', respectively. In the centre, the artist offers ten sentences, which are his analyses of the mental operations that arise in response to these phrases, like: 'Of course, neither is possible. At least, not absolutely. ... I'm so confused. I'd like to forget the whole thing'.

What does it mean to stay alive in an era of constant crises, when the struggle to survive often trumps the ability to live?

The meaning of 'GRAY' and 'NON-GRAY' in PINK remains ambiguous. In terms of STILL ALIVE, they could be associated with the dynamics of polarisation as much as the seeming opposition of life and death, in which living and co-existence become a matter of all or nothing.

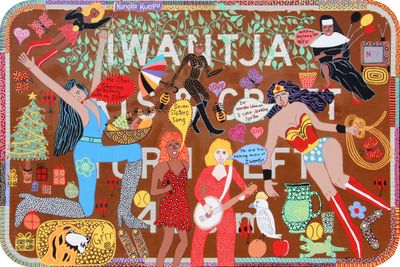

Within such dichotomous conditions, living otherwise becomes an act of vital resistance, as reflected in Kaylene Whiskey's single-channel video Ngura Pukulpa-Happy Place (2022), exhibited at the former Ichinomiya Central Nursing School.

In the video, the artist juxtaposes her traditional Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal culture and knowledge with Western pop culture. She appears alongside sisters from her community, Indulkana, on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in South Australia. Dressed for a party, these kungka kunpu (strong women) chant 'She looks so good/ She got the moves/ All of the ladies/ Nothing to lose' to music as they walk down a road dancing and singing.

As the chanting continues, illustrations pop up on screen of icons like Wonder Woman, superstars like Dolly Parton, plus colourful heart shapes, flowers, and animals. The artist draws these images on a canvas before they fly out over the scene, including depictions of the artist and her sisters as superheroes.

Recalling writer and activist Emma Goldman's famous declaration, 'If I can't dance, I don't want to be part of your revolution,' Whiskey's work represents life as a dynamic and joyful celebration that is rooted in community.

Community is a core theme across STILL ALIVE, where artworks have been curated to connect with the regional context. Mit Jai Inn's painting installation People's Wall (2022), integrates seamlessly into Arimatsu in Nagoya. Decorating the eaves of eight traditional houses and outdoor locations are paintings formed from pastel-painted canvas strips woven together to create hangings.

Resembling the colourful drape-like paper decorations at the Masumida Shrine in Ichinomiya, People's Wall mirrors the tie-dyed fabrics that abound as welcome signs hang outside shopfronts in Arimatsu—a connection to traditional Arimatsu Narumi Shibori tie-dyeing techniques that are famous here.

Artworks in Tokoname, where pottery production has been at the centre of local life since the 12th century, are also closely tied to place. Installed in the Former Earthenware Pipe Factory, Delcy Morelos' Prayer, Horizon, Tokoname (2022), fills the space with cookies and mochi rice cakes made from clay used in Tokoname pottery, mixed with baking soda, cinnamon powder, clove powder, and other ingredients.

Stimulating the senses of smell and touch, Morelos' vast work links Tokoname with Latin America, where rituals within the belief system of the earth-mother goddess Pachamama remain active in parts of the Andes Mountains. Among them, the burying of cookies in the ground to thank Pachamama for providing crops.

Morelos' homage to earth as a life-giving ecosystem, draws in a multitude of beings into the Aichi Triennale's central phrase: 'I am still alive.' Something that Claudia Del Río's enormous clay mural Candour, Anxiety and the Intimate Story (2022) monumentalises. Installed on the wall along a hallway at Aichi Arts Center, various beings appear in relief, from a rough heart-shaped mask with one leg, a couple with corn-shaped bodies, and a salamander with long legs.

Together, these forms extend the existence of 'I' from human to nonhuman—a gesture that STILL ALIVE repeats in its re-interpretation of On Kawara's interrogation of what it means to share time on this planet with others. —[O]

1 Jung-Ah Woo, 'On Kawara's "Date Paintings": Series of Horror and Boredom', Art Journal, Vol. 69, No. 3 (Fall 2010): p.68–69.