A report on Australian representation at the 56th Venice Biennale: 'All The World’s Futures' curated by Okwui Enwezor

On the 120th anniversary of its inaugural exhibition in 1895, Nigerian-born curator, Okwui Enwezor, has this year directed the 56th iteration of the Venice Biennale. Titled All The World’s Futures, the exhibition is centred on re-articulating the politics of representation in the wake of colonialism. Since the nineties, the spike in popularity of the periphery has provided new interest for the so-called Global South, with growing awareness in art from outside the centre. Despite this, international opportunity in both contemporary art, and in life more broadly is certainly far from horizontal, which is why the politics driving the methodology of All The World’s Future, is timely. A total of 136 artists, from 53 different countries appear in the exhibition, including the highest number of Australian artists in the biennale’s history.

Furthermore, this year Australia opened a new pavilion, a moment of spectacle, comfortably positioning the country further within the scope of the international art world. Artists from Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and the central desert region, presented a challenging array of perspectives addressing urgent socio-political issues through painting, social-sculpture, event-based publishing, protest and performative modes of display.

Daniel Boyd presented new painting works for All The World’s Futures in both the Giardini Central Pavilion and the Arsenale sections of the biennale. Boyd’s practice targets a colonial gaze, and engages with a re-articulation for the representation of Indigenous Australians throughout history. In the Central Pavilion, the oldest building in the Giardini, Boyd’s painting is placed in dialogue with artist Robert Smithson, despite their trajectories; this could be a nod towards both artists connection to land. In addition to the Central Pavilion, two paintings by Boyd are also positioned in a long corridor within the Arsenale.

Daniel Boyd, Untiled (TI4), 2015. Oil and archival glue on linen, 164 × 198cm. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia As a starting point in his practice, he visits international archives and historical museums, researching anthropological information pertaining to the history slavery and genocide of aboriginal people in Australia, one such site is the First Fleet section at the National History Museum in London. Throughout this specific archival research, he develops motifs, re-appropriating colonial imagery derived from figures such as Captain James Cook. This figurative layer is placed in conversation with a ‘veil’ of traditional Indigenous Australian dot-painting. This veiling technique allows the artist to draw linage to traditional Indigenous Australian dot-painting practice, but furthermore forms an active dialogue between the two contested modernisms; that of Indigenous and colonial Australia, thus providing a level of transgression. What Boyd fosters is the awareness of the valorisation of colonial histories and the consequences these historical ghosts have upon Indigenous Australians.

Emily Floyd is concerned with the relationship between play and pedagogical infrastructure. The early 19th-century German educator Friedrich Fröbel imagined what we know today as colourful building blocks, which were designed to expand children’s learning capabilities. Similarly, he and his peers developed theories surrounding the criticality of play in relation to a learning environment during formative years. Inspired by these forms and associated theory, Floyd draws reference to these objects as a framework to explore ideas concerning protest, typography, public art, design and the legacy of modernism, often within an overall binary comprised of education and art.

Emily Floyd, Abstract Labour, 2014. Aluminium, two part epoxy paint 300 x 200 x 40 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney and MelbourneHer project for All the World’s Futures is positioned within in the garden in the Arsenale’s Giardino Delle Vergini. Titled Labour Garden (2015), the work is a continuum of Floyd’s public artwork practice. Expanded within a new socio-political context, the sizes of the building blocks are larger than much of her previous work. Indeed, the installation resembles the size of a children’s playground or even an adult’s folly vis-à-vis architectural plaything.

Imagined as a public library, the sculptures house a selection of curated texts dedicated to critical perspectives on work and labour conditions. These documents are seductively published in similar primary colour hues as her sculptures. The collection consists of readings from publications such as Asia Art Archive and e-flux, among others. These pre-existing readings and are then placed in context with newly commissioned texts by the artist. Floyd here re-distributes the collection of documents to new networks. Due to the works location, the site becomes an ideal setting for a moment of retreat and reflection from the overall biennale.

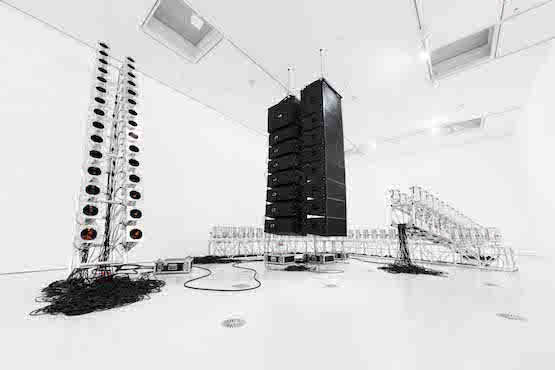

Through a combination of a leftist lens and an interdisciplinary practice, Marco Fusinato explores extremist concerns within art, sound and politics. In the Arsenale, Fusinato’s work From the Horde to the Bee (2015) is positioned within an intersecting rhombus chamber. Within an exhibition crowded with didactical works, Fusinato’s contribution presents an active break from a more normalised system of display. Upon witnessing the work, the viewer is faced with a large table, with publications stacked up around the edge and in the middle of the table are some discarded Euro notes. The viewer is invited to take a publication upon exchange for a payment to be left on the table. Over the course of the exhibition period, the monetary value in the middle of the table will increase, and the amount of publications surrounding the table will consequently decrease, clearly documenting the process of a capitalist exchange-value.

Marco Fusinato, Aetheric Plexus (Broken X), 2013. Exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne and Sydney, Australia The work is more than this public event; the remaining funds will be re-distributed to Archivio Primo Moroni, a self-organised archive in Milan. The publication itself is a DIY anthology of writings from the archive, including critical and militant writing from the 1960s to present, which aims to juxtapose leftist ideology. Apart from providing a fascinating archive, Fusinato employees the consumer spectacle as a conceptual basis but also demonstrates the relationship between spectacle and audience, and exchanges of action and reaction. Using rhetoric, the artist questions prevailing conditions and behaviours derived from capitalism, and reminds audiences of the prominence of these tropes within our lives while questioning their authenticity.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye (1910 –1996) was among the first generation of Indigenous Australian artists who resisted the Australian government’s policies of assimilation; instead opting for Indigenous autonomy. Kngwarreye is an Anmatyerr woman, and central to her practice is the exploration of her history as an Indigenous Australian woman, specifically aboriginal concerns pertaining to oral histories and sacred relationships to land. Her practice emerged alongside the growing interest in Aboriginal art from the centres of the art world, which grew rapidly from the 1970’s onwards. Kngwarreye is famous for shifting the expectation that aboriginal art must be bound to traditional iconography, instead exploring colour-based abstraction.

In All The World’s Futures, audiences can see Kngwarreye’s work Earth’s Creation (1994) in the Giardini Central Pavilion. The painting is an abstracted representation of the Australian north-central desert region of Alhalkere after the rain season. As mentioned in the didactics accompanying her work, the artist said that the painting represents ‘green time’. In a crowded exhibition, it was refreshing and comforting to see the work given an entire room of its own, allowing for a certain respect for the artist’s spatial concerns and connection to land. In context of the biennale, Earth’s Creation, even today, challenges the tropes placed on Indigenous Art from a colonial gaze.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Earth’s Creation, 1994. Synthetic polymer paint on linen 4 panels, each 275 x 160 cm. Courtesy of Mbantua Gallery and Cultural Museum, Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia Photograph: Mbantua GalleryAlthough not an official participant at the Venice Biennale, Brisbane-based artist Richard Bell staged interventions at various sites across the city with collaborator and fellow Indigenous rights activist and broadcaster, Alec Doomadgee. They together presented multiple encounters of Bell’s work Aboriginal Tent Embassy. The work draws reference to Redfern based Aboriginal activists Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Tony Coorie and Bert Williams, who in 1972 set up a protest camp under a beach umbrella on the lawns of Parliament House in Canberra that they named the ‘Aboriginal Embassy’. The Aboriginal Embassy’s protest at Australian Government policy is pivotal for Indigenous Land Rights Movement and placed issues of Indigenous Land Rights, health and housing at the forefront of Australian politics. This new iteration by Bell and Doomadgee continues this linage, but furthermore aims to highlight contemporary issues facing Indigenous Australian’s today, most notably the forced removal of regional Indigenous communities in Western Australia. For the Venice Biennale, Bell and Doomadgee staged many pop-up protest events, which happened in real time and were also documented extensively through social media channels. Controversially, one such staging provocatively took place outside the opening of Fiona Hall’s exhibition at the new Australian Pavilion.

Richard Bell and Alec Doomadgee, Aboriginal Tent Embassay. Image courtesy Richard Bell and Alec DoomadgeeIn an exhibition dedicated to politics of representation, though not officially connected to the Biennale, Bell’s intervention is a timely reminder of what actually art can do in terms of mediating an activist agenda to a public. In light of this questions are raised including; what happens to politics when they become institutionalised? Does seeing certain work in the biennale assist in changing our collective reading of a canon, history or peoples? How does it make a difference if a protest is staged in a museum or on the street?—[O]