Ai Weiwei 'Evidence' At The Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin

Ai Weiwei, 2012. Photo: © Gao Yuan.

Ai Weiwei's current survey exhibition at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin marks the artist's largest solo project to date, consuming 18 rooms and 3,000 square metres of the institution's floor space. Only open to the public since April, Evidence has already experienced an overwhelming reception that has become the standard for Weiwei as one of the world's most prominent contemporary artists.

Featuring pieces spanning from the late 80s to the present, Evidence contains a mixture of the artist's modest student-era works alongside his more ambitiously scaled productions of the last few years. The centrepiece of these recent projects is_Stools_ (2013), an installation of 6,000 wooden stools from the Ming and Qing dynasties set in the gallery's main atrium. The dimensions of these simple chairs are roughly uniform, yet their gradating colours have been assembled to reference the colour scheme of the gallery's tiled floor, rendering the work site-specific and historically situated at the same time.

Regrettably, the artist could not be present for the installation of this monumental work, nor is his attendance during any point of the exhibition likely due to the confiscation of his passport by the Chinese state. For this reason, Evidence speaks to us from an unfortunate, yet equally unique standpoint — instead of presenting this exhibition to us in person, the artist speaks to the Western viewer from his studio outside of Beijing. The overarching message Evidence attempts to relay to the viewer, however, lacks the conviction one would expect from an endeavour this comprehensive and ambitious.

When reviewing the timeline of Weiwei's artistic and conceptual development over the years, the title Evidence can be interpreted on a number of levels. His earliest ready-made sculptures mimicked the devices of the evidence object (often from a Dadaist standpoint) to cast light on the draconian policies of the Chinese nation-state in humorous and ironic ways. From the mid-90s to the mid-2000s, Weiwei channelled his practice into an exploration of state control and repression by documenting everyday life and the Chinese people. Such documentation was clearly a political act given that China controls its international image to such an intense degree that any alternative representation would inevitably contest its propaganda.

If there is one constant throughout the ebbs and flows of Weiwei's diverse practice, it is the grappling with history and its uses and abuses ...

This utilisation of the art object as evidence would eventually impact Weiwei's own liberty when in 2011 Weiwei himself was detained for 81 days in a secret government holding cell, an experience which can be seen to have shaped much of his artistic output since. To the credit of curator Gereon Sievernich, these varying expressions of evidence were apparent throughout the exhibition, as well as the curatorial ambition to articulate a wider dialogue between the ideological terrains of the East and West.

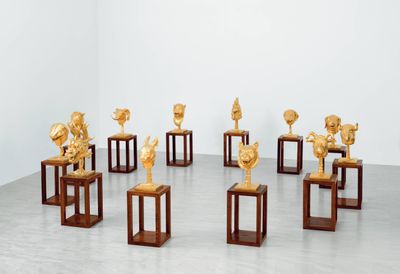

This theme informs interpretation of Weiwei's most recent works, which explore the concept of evidence quite literally to foreground topical events and issues within China. His project to document the victims of the Sichuan earthquakes of 2008 (which left 70,000 dead, including 5000 children) and the sculptural project that rose out of this investigation—Forge (2008-2011)—presents a clear example of this.

Because these works operate so literally as types of evidence objects in their own right, large amounts of information is required to comprehend the artist's motivations and underlying intentions. As crucial as this comprehension is for totalising Weiwei's practice in any meaningful way (particularly his most recent works), it leaves little room for the viewer to assess the pieces in terms of their aesthetic success.

Many of the catalogue essays and critical responses to the exhibition take cue from this situation, and remain focused on summarising and repacking this information (particularly in regard to the artist's biography) to fully explain the exhibited works, rather than making an argument or assessment of how effectively the exhibition functions as a whole.

When we consider the exhibition in this way, many gaps remain within the ideas Evidence offers regarding Weiwei's stylistic and conceptual direction (aside from the blatantly apparent 'progression' of the artist having more money and resources at his disposal). Ideas about why the artist marries particular concepts to aesthetics are thin on the ground, superseded by simpler explanations of how Weiwei and his assistants executed each project.

Asking why he was motivated to make these pieces becomes particularly important when many exhibited works appear to be either rehashing versions of older series, such as Han Dynasty Vases with Autopaint (2013) which mimics his 1995 photographic series Dropping a Han Dynasty Vase; or the inclusion of Studies of Perspective which, although completed during 1995-2008, is presented as a 2014 re-edit. Likewise, many works referencing the artist's incarceration find their impact through banking on the spectacle of this event, but hold little impact in any other respect.

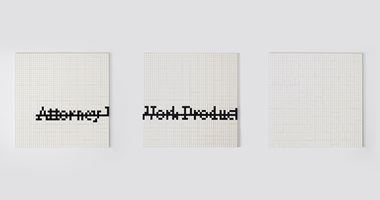

The recreation of Weiwei's cell which viewers could line up to walk around in, or the installation Untitled (2011), presenting all the hardware confiscated from Weiwei by the state in a grid formation on the floor, have little aesthetic value outside of their role as evidence objects. Alternatively, some of these newer works seem to return to the artist's troppe of casting everyday or 'worthless' objects into sculptures of significantly expensive materials such as marble, jade and stainless steel. This time, these sculptures were of handcuffs, coat hangers and containers referencing Weiwei's time in detention. Their rendering into new materials is undeniably beautiful, though stylistically predictable.

If there is one constant throughout the ebbs and flows of Weiwei's diverse practice, it is the grappling with history and its uses and abuses — history which spans centuries, but also the history that is being made as we speak.

It remains unclear whether Evidence is a demonstration of Weiwei's attempts to lend cohesion to a practice which now deals not just with the national history of China and its relation to the West, but also with his personal history as a dissident artist, or whether it demonstrates the artist forgoing the presentation of a vision to ride on his immense celebrity status.

Although containing some significantly historical works from Weiwei in a space which surely does them justice, Evidence does not maintain this energy when it comes to the showcasing of his current practice and its potential rationales. —[O]