‘An Opera for Animals’ at Rockbund Art Museum

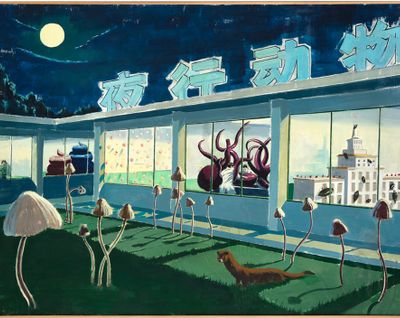

Yang Shen, Nocturnal Animals (2012). Oil on canvas. 150 × 200 cm. Courtesy the artist and MadeIn Gallery.

An Opera for Animals was first staged at Para Site in Hong Kong between 23 March and 2 June 2019, with works by over 48 artists and collectives that use opera as a metaphor for modes of contemporary, cross-disciplinary art-making.

The exhibition's second iteration takes up a large portion of the Rockbund Art Museum (RAM) in Shanghai (22 June—25 August 2019), where works by 53 artists have been curated by Para Site's Cosmin Costinas and Claire Shea, along with RAM senior curators Hsieh Feng-Rong and Billy Tang.

The exhibition's shift to Shanghai has resulted in changes to its substance, given the fact that the force of its main theme—the developed world's fraught relationship with modernity—has less impact in China, where a strong belief in progress still persists.

While the number of artists has increased, several key pieces could not be presented, which points to possible political sensitivities surrounding the exhibition. These particularities serve to make the show's transition from Hong Kong to the mainland more pertinent, especially given the tense political climate in the former British colony.

An Opera for Animals is loosely divided into five untitled acts that play out from the second to the fifth of RAM's six floors, with a billboard by Yee I-Lann, Kerbau (2007), depicting traffic cones and water buffalo, situated outside the museum's Huqiu Road entrance, and one video work by Angela Su located on the sixth floor, depicting figures that shift between animalised humans and anthropomorphised animals (Voigt-Kampff Test, 2019).

Entering the museum on the second floor, viewers encounter Great Performance (2014), an installation combining video and sculpture by Zhao Yao that at first resembles a pair of animal pelts hanging from the ceiling in a manner reminiscent of Chinese funereal banners.

These pelts are in fact synthetic leather printed with a pattern derived from two newspaper photos and treated with a kaleidoscopic effect using photo editing software. A video displayed next to these 'hides' shows dancers wearing them in an outdoor performance reminiscent of tribal rituals, thus conveying this exhibition's key concern: the collapse of the modern and the pre-modern.

The vernacular in which the show communicates its theme is made evident as viewers pass through black velvet curtains on the second floor and enter a passageway painted crimson—a colour reminiscent of the fabric used for curtains and seating in theatres.

Beyond its associations with performance and opera, curator Costinas claims the colour carries connotations of colonialism, a theme explored in greater depth in Hong Kong, but still resonates at RAM, which is situated in a building established by the British Royal Asiatic Society in 1932.

Beyond this crimson passageway, several works level critiques at governmental authority. In Indonesian artist Heri Dono's installation Born and Freedom (2004), which expresses cynicism over the supposed liberalisation of Indonesia following the downfall of President Suharto's military junta in 1998, five fibreglass human-bird gods with radios for chests play a distorted version of John Barry's song 'Born Free'.

These figures are placed in a line along the wall, each with a lead attached to a dog-like creature with pointed horns and a grinning mouth that stands on the floor in front. Continuing on the second floor, Colombian artist Beatriz González's Interior Decoration (1981) is a massive silkscreen on fabric that hangs across a false opening on the wall, resembling a curtain.

Its surface depicts Colombia's then-president Julio César Turbay Ayala partying with guests, turning a blind eye to the hardships the people of Colombia were suffering at the time as the country experienced a succession of insurgencies.

Other works consider the mystical qualities of contemporary urban landscapes. Cui Jie sees architecture as a contemporary manifestation of tribal totems in works such as Escape (2017), her oil painting of the Hangzhou Honglou Hotel, and, beside it, her 46-centimetre-tall white 3D-printed model of the Chongqing Marriott Hotel (2019), both of which are augmented with her own fantastical forms.

Nearby, Korean artist Lee Bul's Untitled Sculpture W1 (2005) hangs from the ceiling. Made of building waste materials arranged to resemble an elegant chandelier, Lee makes visible the latent primitivism of contemporary construction, just as Cui Jie uncovers its magic.

On the third floor, the show progresses with a number of works that draw visual or metaphorical inspiration from animals and nature. Several ink on rice paper scroll paintings by Guo Fengyi, an outsider artist born in 1942 who passed away nine years ago, include SARS series (2003), Lugu Lake — If Women Ruled the World (2002), and The Human Brain, From The Beginning up Until Now, Has Passed Through All of These Animals (1995).

These hang side by side in their own designated space, and depict half-human and half-plant figures in fine and delicate brushstrokes. Elsewhere, Vocal Communications (2014) by late Inuk artist Tim Pitsiulak captures a mermaid wearing a mask: a combination of the natural and the imaginary that characterises Pitsiulak's practice, conveying his respect for Inuit beliefs and visual culture.

In Healing lions on a shingles sufferer, drawn by Lok Chitraka (2019), composed as a series of three photographs, Nepalese artist Lok Chitrakar documents the process of painting 'healing lions' on the body of patients in order to help them gain strength from the sacred animal.

Next to Chitrakar's photos is Panorama 3 (2019), a site-specific installation by Wang Wei: a curved wall painted with a forest scene taken from a fresco from the Nocturnal Animals Section at the Beijing Zoo, turning audiences into the animals in an enclosure.

The mythical, natural, and technological continue to converge on the fourth floor, where Visible Woman (2018) by Jes Fan presents a female body that references the pull-apart 'visible man' models used to illustrate human anatomy.

Made of semi-transparent resin, female organs displayed on oversized runners found in model-making kits highlight the ability to change the human body, adding and subtracting almost at will.

Nearby, a giant silver cockroach resting upon a bed-like structure forms American artist Candice Lin's Metamorphosis in Space (human sized cockroach) (2013). Recalling Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis, in which the main protagonist, Gregor Samsa, awakes one morning to find he has transformed into an immense insect, the cockroach has been given a human vagina.

The addition of this anatomical feature makes reference the Coridromius insect in Australia, which has developed paragenitalia as a response to traumatic insemination by male insects, preventing it from being severely wounded during excessive intercourse.

Here, evolution serves as a metaphor for a kind of postmodern progress in which being human is no guarantee of ascension into the future.

On the fifth floor, a final act interrogates opera as a Western art form, with works that use modern forms of documentation as a tool to preserve and disseminate the traditions that it threatens to make extinct. (Despite the location, Chinese opera is only touched upon briefly in this show in a photograph by Chen Qiulin on the second floor, which references the epic love story, Farewell My Concubine.)

Whistling and Language Transfiguration (2012) by Gala Porras-Kim, for example, comprises a collection of notation diagrams of the Zapotec language, a form of whistled communication belonging to the indigenous population of the Tlacolula Valley in Oaxaca, accompanied by recordings of a collection of local stories that the artist turned into an LP and musical score.

Similarly, Mexican composer and musicologist Gabriel Pareyon spent more than ten years researching musicology and linguistics to create a notation system for the native instruments used in Xochicuicatl Cuecuechtli (Ribald Flowersong) (2012), the first opera in the Nahuatl language of the Aztec Empire that uses indigenous instruments from ancient Mexico.

As curator Hsieh Feng-Rong explained during the exhibition's press preview, while 'the Western concept of modernity might be the starting point of the critical context here,' An Opera for Animals does not focus on the 'differences between Western modernity and other cultural systems, but how these systems interact, co-exist, and understand each other, or even repel each other and generate new consciousnesses.'

Scottish artist Euan MacDonald's 9,000 Pieces (2010) seems to anchor this sentiment neatly to the context: a video that captures an instrument factory in Shanghai, where 9,000 different piano parts are being tested.

Presenting an emblematic source of classical music as a form of industrial noise, 9,000 Pieces echoes the transitions that have taken place in China, where both the piano and opera were used to promote Communism, itself a Western import, before the instrument fell out of favour during the Cultural Revolution.

China is now the largest piano manufacturer worldwide, producing 80 percent of the global supply, with piano classes playing an important role in delineating the classes that Communism was meant to abolish.—[O]