Snowed Under: Armory Week 2018

Hans-Peter Feldmann, Woman with lipstick. Oil on canvas. 74.9 x 63.2 cm. Installation view: 303 Gallery, Independent New York (8–11 March 2018). Courtesy Ocula. Photo: Charles Roussel.

At the opening of the seventh edition of the Spring/Break Art Show (6–12 March 2018), people were already talking about the blizzard. The neon lights glaring through the windows at number 4 Times Square gave the former floors of Condé Nast an atmosphere of urgency. The exhibition platform, which hosts curator-led projects, seemed as guerilla as its earlier editions, but perhaps just a smidge too large. Launched in 2012 in St. Patrick's Old School by Andrew Gori and Ambre Kelly as a low-cost antidote to art fairs, Spring/Break has clearly grown, receiving over 500 applications this year for around 150 spots, compared to 39 selected curators in 2014 and around 80 in 2015.

Spread across two floors and arranged in a series of conference rooms and former offices, curated spaces were found in every conceivablesquare inch, including the hallways and lobbies. Responding to the curatorial theme 'Stranger Comes to Town', curators focused on work thatbent the edges of the familiar, calling for interpretations of 'foreignness, migration, assimilation, and the alchemy of two or more dissolving into each other'.

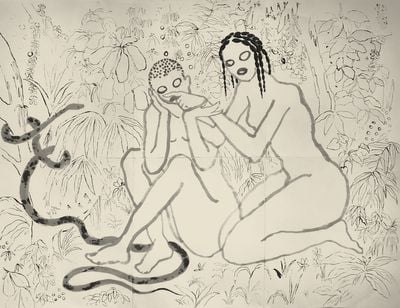

The variety of practices on show mirrored the fair's affordable scale, from the free exhibition space and low entry charges (5 US dollars) to the art on sale; and what could be seen in the flesh can also be seen on the fair's online selling platform, springbreakartfair.com. Risa Hiratsuka, curated by Brooke Nicholas, showed cute wax candles sculptures of cartoon animals, going for between USD45 and 60, while Chioma Ebinama's series of Japanese monoprints and ceramic sculptures of anthropomorphic and humanoid figures curated by Raphael Guilbert—including Grace (2018), an Adam and Eve-like couple in a forest—are priced between USD1,500 and 3,500. A naïvely painted hot dog by Walter Robinson, curated by Arielle de Saint Phalle and Taylor Roy, is USD4000, while Bailey Scieszka's coloured pencil and gold leaf drawings on paper of fairy-like characters chewing on Tide Pods—a reference to a recent wave of young people doing exactly that—are USD1,900 each. (Scieszka was curated by Emily Davidson and Samantha Strand.)

It is almost impossible to follow trends at Spring/Break, as the omnivorous show puts forth what amounts to a bit of everything, from neons to installations, small drawings, paintings, photographs and editions. Amid the creative chaos, I found respite in moments of clear vision, gravitating towards Andy Harman's solo booth at the entrance. A suite of crushed-velvet orange sculptures, which looked somewhere between appendages, Cheetos, and molecular forms, were arranged against walls and floors, sometimes slumped between both: a collapse that felt appropriate in a space like Spring/Break, which is dominated by the interplay of transparencies and structures absorbed into larger structures. This is but one fair of many taking place in New York City this March, after all.

Matthew Morrocco's 'Complicit' series (2010–2015) of framed colour photographs offered another reprieve: intimate, mostly nude images of older men whose creased faces and frail bodies gave a presence to those lovers left behind after the AIDs epidemic. 'While most art fairs focus almost entirely on sales, I thought it was a welcome relief to be in a place where showing the work was paramount', the artist noted in conversation. Like his work, which features tender moments between strangers, Morrocco felt it was important to protect his subjects and images through context. 'In my mind, this work lives in a place between the weird corporate enterprise and a more fluid earnest and inclusive place that Spring/Break seems to offer.'

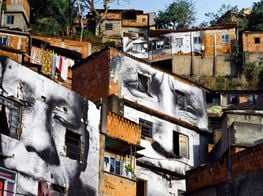

I took this thought to bed and woke up to less snow. But on my way to Piers 92 and 94 for The Armory Show (8–11 March 2018), the flakes began to swell. By the time MoMA Director Glenn Lowry and fair director Nicole Berry began their opening remarks at the 7 March press conference, the flutter became a deluge. The VIPs arrived anyway, greeted by So Close (2018): JR's billboard-sized outdoor installation of black-and-white images depicting cloaked immigrants sourced from the archives at Ellis Island, which were manipulated to feature the faces of those living in the Zaatari refugee camp on the border between Syria and Jordan. Visible from the highway, the installation set a sombre tone at The Armory Show's entrance.

Inside, things were more colourful. Gagosian's booth was visible from check-in. The blue-chip giant re-joined The Armory Show this year after a four-year hiatus, with an eye-popping solo presentation of works by Nam June Paik, including Lion (2005), a flashing temple of televisions installed in the centre of the booth with screens looped on footage of lions roaring. Galerie Perrotin showed small chromogenic photographs from the series 'Riffs on Real Time' (2002–2009) by Leslie Hewitt alongside Pieter Vermeersch's gradated paintings, a few of which covered the booth walls with tones of bright orange.

Down the aisles, a focus on things that could be flat-packed emerged, with very few site-specific installations or large sculptures to speak of. Instead, there was a stream of photographs and paintings, from Zanele Muholi's photographic series of self-portraits from 2016 at Yancey Richardson, Annette Kelm and Roe Etheridge's prints at Andrew Kreps Gallery (archival pigment and dye sublimation on aluminum respectively); to André Butzer's paintings of wide-eyed lawyers at Nino Mier Gallery, and P.P.O.W. Gallery's selection of contemporary and historical paintings, photographs, and prints by Ramiro Gomez, Joe Houston, Erin M. Riley, Hunter Reynolds, Betty Tompkins, Robin F. Williams, and David Wojnarowicz

One successful aberration was Vanessa Baird's An amazing thing happened to me: I suddenly forgot which came first, 7 or 8 (2018), which transformed OSL Contemporary's booth into a Paul McCarthy-esque nightmare by cloaking the booth walls with large, curtain-like scrolls covered in furious paintings of cartoon characters such as SpongeBob SquarePants and Snow White engaging in erotic and murderous escapades (sometimes both). When I mention McCarthy to OSL Contemporary director Emilie Magnus, she nodded; the artist met McCarthy recently and they became 'fast friends'.

More familiar faces could be found at PSM, where the Pink Panther and Smurfs lurked in the paintings of Nadira Husain. But it was cartoon cats at OTA Fine Arts that stole my attention: a 2018 series by Nobuaki Takekawa, which comprised colourful feline-filled woodblock prints on paper touting art fair appropriate one liners including: 'Believe the Conspiracy Theory and Gnaw Your Right'.

My preconceived ideas about The Armory Show this year were largely proven untrue; the neons and mirrored trophies I was expecting to see were at a minimum. A new layout designed by Bade Stageberg Cox and a reduction in exhibitor numbers made The Armory Show's 24th edition feel more polished and international than ever before, with 198 galleries from 31 countries and 66 new exhibitors, including Galerie Eigen + Art and Regen Projects.

Likewise, dealers expressed a renewed sense of purpose, despite the bad press art fairs continue to receive. Rejecting the backlash—and withdrawal—was Daniel Roesler, Senior Director and Partner of Galeria Nara Roesler: 'Fairs are an essential element of the work that we do', he noted. The gallery's booth offered a beautiful display of paintings and sculptures by artists including Julio Le Parc and Vik Muniz, whose photographic print of a gravelly, re-staged version of Tarsila do Amaral's painting of a fleshy distorted body next to a cactus, Abaporu (1928), connected with Amaral's current exhibition at MoMA (Inventing Modern Art in Brazil, 11 February–3 June 2018).

Thursday brought its own onslaught of activity, with the snow melting to clear the way for the vernissages of Independent New York, NADA, and Collective Design Fair (all 8–11 March 2018). The former was located in Spring Studios, just a ten-minute walk from the latter two, which were hosted in the Skylight Clarkson building on the Westside Highway with completely different attitudes.

With over 100 galleries from 36 cities, NADA served up a rambunctious mix of naïve paintings and naughty ceramics. I found myself ensconced once again in solo booths focusing on artists like Willie Stewart, whose coloured pencil drawings and inkjet printed sculptures of colour charts and postcard perfect imagery were showing at Moran Moran; and Genesis Belanger's pastel-coloured tabletop sculptures from 2018 of cigarettes, bouquets and pill-topped tongues at Mrs. Gallery's booth, which had sold out by the time I got to it.

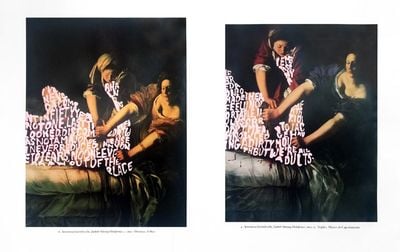

Offering a more critical, context-specific slant with regards to the political situation in the United States was Alexandra Bell at Recess. Bell's diptych of digital prints, A Teenager With Promise (2017), depict two front-page stories from the New York Times about Michael Brown, the unarmed teen shot dead by the Ferguson police in 2014. Bell's prints censored out almost the entirety of the article leaving only a few key phrases behind, so the article read: 'Officer Darren Wilson fatally shot an unarmed black teenager named Michael Brown'.

Dealer Ellie Rines of 56 Henry showed BIG BAD PICKUP (2017), a guitar decked tower vibrating with music, by Nikita Gale. The booth felt like an extension in some ways of Rine's New York space, where she is also showing the Los Angeles-based artist (Extended Play, 17 February–25 March 2018). Tactile, playful and critical of the art establishment's investment in the dominance of minimalism, Gale's stepped sculpture exemplified the art on view throughout NADA, despite its booth-dwarfing size.

One door down at Collective Design Fair, a design and contemporary fair now in its sixth edition, things were more communal. The fair, which hosted around 30 exhibitors this year, felt like a large roaming salon, with booths by galleries such as Carpenters Workshop Gallery and Nina Johnson arranged over a large industrial floor into neat squares surrounded by open space.

The main attraction came in the form of Collective's commissioned architectural interventions that surrounded the formal booths. Walking through Justin Moran's dreamy curtain forest made of transparent ombre fabrics felt otherworldly, as did a bubble structure made from polyethylene fire retardant plastic sheeting designed by writer and artist Jesse Seegers and landscaper designer Brook Klausing. I found Klausing and Seegers hanging out inside their incense-filled garden surrounded by plastic walls on opening day. 'They breathe', said Seegers, as he opened the zipper flap of the inflated hallway, which softly collapsed as each person entered, displacing the air inside.

My moment in the design bubble didn't last long, but long enough to take Harry Nuriev's purple dining-room table for a spin at Crosby Studios' booth. Built on a kind of carousel, the purple metal table, titled My Reality (2018), spun guests around to view a panoramic photograph plastered onto the booth walls that surrounded them. The image depicted an apartment complex that the designer lived in while in Moscow (he recently moved to New York to found Crosby Studios).

Further downtown at Spring Studios, Independent New York picked up accolades for its sunny, floor-to-ceiling windows and finite offerings. Helmed by artistic director Matthew Higgs, the invite-only fair has matured into a place where collectors can expect works, both historical and cutting-edge contemporary, at approachable prices (USD100,000 and under). This is a stage where galleries like Clearing, Canada, and David Kordansky Gallery—whose exemplary tastes have been backed by both museum and market interest—thrive. Their solo booths, respectively focusing on Ruby Neri's ceramic vessels covered in bare-breasted women, the painted tabletop handball courts of Harold Ancart, and the black and white ceramic vases of Elisabeth Kley, sold out within the first day.

In conversation, Independent New York Director Alix Dana considered this Independent the best edition to date, with 57 galleries participating, including 303 Gallery, Jan Kaps, Karma, and Marlborough Contemporary. Commenting on the difficulties galleries face, which similarly impacts an art fair's success, Dana pointed to the consideration that Independent takes not only when it comes to planning or staging the fair, but also what happens afterwards. While emphasising the importance of 'a tight focus on the content of the overall presentations' during the fair itself, Dana explained: 'Every decision we have made around this year's event has been towards supporting our participating galleries and artists beyond the four days of the fair.'

Highlights at Independent included Rebecca Ackroyd's solo presentation at Peres Projects, her first in New York. The booth showcased gouache, charcoal and soft pastel on somerset satin paper renderings of flowers zoomed in (Civil Soup and Rot, both 2017); and a wall-assemblage evoking a metal door shutter made from jesmonite, graphite powder, photocopied images, and tape (Carrier 2017 UK, 2017). At the centre of this arrangement were Glory Still and Glory Slips (both 2018): two life-sized figures seated on the floor made out of steel rebar, chicken wire, plaster, wax, acrylic, synthetic hair, and jesmonite, with red-tinted windows for chests, kneecaps and genitals. 'I like the idea that there is this collapse between inside and outside', Ackroyd told me. 'There is something beautiful and tragic about this demise of boundaries.'

Ackroyd's work felt aligned with Harman's Cheeto-coloured sculptures at Spring/Break in their allusion to boundaries and the dispelling of them within structures that already exist—but thanks to the rigidity and freneticism of fair week, there were very few moments for visitors to thoughtfully connect the dots between booths, let alone the fairs themselves. Instead of shuttles between the locations, for instance, there was only a sense of every collector, visitor, and curator for themselves.

This disconnection felt compounded by The Armory Show's decision to move its dates one week later than normal, leaving ADAA (the Art Dealer's Association of America) to open one week before the other fairs (28 February–4 March 2018).

But while reports noted an absence of international visitors at ADAA's 30th Anniversary edition at the Park Avenue Armory, the quality of work shown by the 72 galleries—many also participating at one of the Armory Week fairs—was far from lacking. Continuing a trend for solo booths was Casey Kaplan's stunning selection of paintings by Jonathan Gardner; Pace Gallery's concise 30-year survey of Tony Smith's modular oil paintings and sculptural maquettes from the 1950s to 1970s; Galerie Lelong's focus on Mildred Thompson's singular abstract paintings, also on view in the gallery's New York space (Radiation Explorations and Magnetic Fields, 22 February–31 March 2018); Marian Goodman Gallery's collection of candy coloured polyurethane, lacquered aluminum forms by Nairy Baghramian; and Cheim & Read's colourful paper over chickenwire wall sculptures by Lynda Benglis that covered the booth.

If Armory Week 2018 is anything to go by, it seems that in Trump's America the New York art world is rather content with remaining entrenched in old divisions. There is such a wave of collective energy around the fairs that it seems strange this has not been nurtured more by a week that brings so many people from around the world together. Yet, with a contracting market and a rising number of participants, wouldn't the art community be better served by banning together against the storm? —[O]