Artful Manifestations

For the first time since 1996, this year’s edition of Manifesta was curated by an artist, German-born Christian Jankowski. Titled What People Do For Money – Some Joint Ventures, the labour-themed biennial was all about collaboration with unnamed specialists. Frankly, it’s not that different from the usual working process of many contemporary artists, with the artists responsible for conceptualising the work, giving orders to a team of collaborators and getting all the credit, but… whatever. Given Manifesta’s budget of a reported 5 million euros—with a rumoured 8000 euros going to each of the artists to produce work, the biennial would have been better titled ‘What people do for no money’.

Straight off the plane, I ventured into Zurich’s apocalyptic ‘summer’ weather and headed to the Löwenbräukunst, a converted brewery and one of the main Manifesta venues. I found myself standing in a room full of shit, and by that I don’t mean bad art fuelled by boredom and dilettantism, although there was still your fair share of that, but literally Swiss shit. LA artist Mike Bouchet presented The Zurich Load: a day’s worth of processed and compressed human faeces arranged in cubic blocks, produced in collaboration with the Werdhölzi Wastewater Treatment Plant, or as the artist says, ‘in collaboration with the entire city’s population’. It takes a village. In an attempt to make the work more bearable it was treated with a ‘unique’ fragrance—something between the rotting breath of Nosferatu, merde, and the chemical smell of a morgue. But it still didn’t come up smelling roses and clung to me for the duration of the day. Next, I wandered over to a massive wall of vaginas and female masturbation portraits, a collaboration between Andrea Éva Györi, and a ‘sexpert’, which gave me some welcome relief from the bowels of hell. Welcome to Manifesta!

Downstairs at the Schwartzescafe, a black box room-cum-cafe designed by Heimo Zobernig and decorated Wunderkammer-style with various artworks, I bumped into Polish artist Paulina Olowska and the space’s curator, Niels Olsen. I enlisted them in an impromptu photo shoot with Karen Kilimnik’s Rosemary’s Baby installation and pile of party favours scattered on the floor, which wouldn’t have looked out of place in Keith Richard’s ‘medical’ cabinet. Nearby, witnessing our antics, Miami collectors, the Rubells, were lunching on bratwurst, practically the only thing on the menu after a 30 minute wait. ‘Look at that! They came all the way from Miami to eat Swiss sausage!’ commented a collector companion. Later I spotted Hans Ulrich Obrist having a self-reflective moment, having recognised his own likeness in a work by Megan Marlatt which consisted of large papier maché reciplicas of the heads of the Serpentine curator and critics Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz. Manifesta curator Jankowski, was spotted around the biennale sporting the big head.

On Sunday at Galerie Gmurzynska, a wonderful Kurt Schwitters: Merz and Zaha Hadid exhibition brought together 75 works by the Dadaist within a space designed by the late architect to pay homage to Schwitters’ Merzbau. Since Galerie Gmurzynska happens to be in the same building that was once home to the famous Galerie Dada, and Zurich is in the throes of celebrating Dada’s 100-year anniversary, the exhibition couldn’t have been more timely. Although outside and over cigarettes, exhibition curator and director of the revived Cabaret Voltaire Adrian Notz informed me, ‘Dada is dead … She is a whore who has been f*&%ed too many times, from behind'. Instead, Notz plans to usher forth a new era of Dada. ‘We want to destroy ISIS through Dada’. More on that in a later interview.

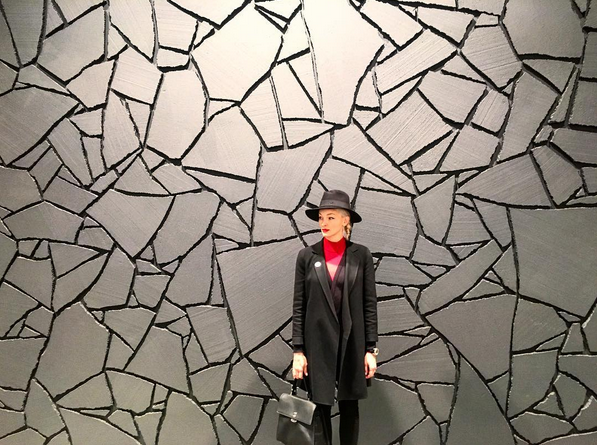

The turnout at the Gmurzynska opening typified the conflation of art, entertainment and money that makes drinking at openings so fun and so necessary. Proudly wearing my souvenir from Sylvie Fleury’s Manifesta exhibition, a badge reading ‘We don’t need more balls to play’, I bumped into one of the British Kents (the Duke or the Prince, I couldn’t be sure, pressed up against Hadid’s curved futuristic iceberg wall); Zaha Hadid’s right-hand man, senior architect Patrik Schumacher, who saw the project to completion; and Lindsay Lohan (God please don’t tell me this is potentially another Hollywood star planning an art career?!), who was easily missed amongst the handful of former Swiss beauty contestants onto husband number three. In the heartland of private Swiss banking, this was the place to find husband number four. Notz cheekily played on this, naming the gallery ComMERZ Bank for the duration of the exhibition. What people do for money, indeed.

Post-Manifesta, it was a hop, step and a jump to a former psychiatric clinic in St. Urban for a Chinese contemporary art exhibition presented by ShanghART, where collector Uli Sigg gave a talk about his collection. And from one cell to another, once in Basel I checked into a former prison and monastery (I’m not sure which came first), while my chain-smoking Parisian companion checked into a hotel with the vibe of a modern asylum (there’s a theme here)—an ugly glass building with sterile plastic furniture and suicide-proof windows. ‘Darling, I can’t even kill myself if I try in that room. And it’s so depressing you really want to. Where will I smoke??!!’ Accommodation in Basel can only be likened to Scottish boarding school food. It’s the bare minimum and gets you through the week, but no more. Call it character building. We headed to Unlimited as fast as we could.

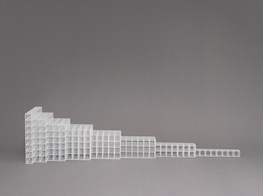

This year was one of the most crowded previews since its inception in 2000, but it was also one of the most exciting. The Gianni Jetzer-curated Unlimited section delivered an impressive section of institutional (big) scale works, with a selection of historical and new pieces. Historical art is so now. There were installations by Hans Op de Beeck, whose Collector’s House (2016) was an Instagram sensation; Sol LeWitt, with his 1993 black and white Styrofoam wall; Gilberto Zorio’s sound installation Microfoni (1968) where I once again took the microphone and cleared the room with my rendition of Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’; Joseph Kosuth’s 1968, Titled (Art as Idea as Art); as well as newer works by William Kentridge, Chiharu Shiota, Ai Weiwei, AA Bronson and Kader Attia’s colonial critique installation.

The Art Basel First Choice VIP opening Tuesday morning saw a line of hundreds of fairgoers huddled under umbrellas in the rain. It was like witnessing a queue of creatives at a public pillorying of Boris Johnson. Apparently 1000 people were cut off the first choice list this year, but with new security measures in place following last year’s Miami knife attack, and because ‘these are changing times,’ says Marc Spiegler, getting into the fair took a lot longer than usual. ‘Seriously, what’s the worst someone will walk in with at Basel? An oversized Panerai that can be used as a weapon?’ quipped one irate collector in front of me. We just cut the queue and went through the uncrowded Unlimited entry. Queues are so pre-perestroika.

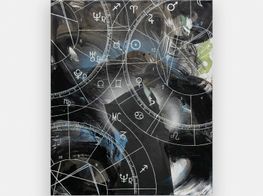

Hours into the opening I heard a gleeful collector declare in the VIP lounge, ‘Painting isn’t dead!’ Indeed, painted works on canvas were on offer from a number of galleries: Günther Förg’s works seemed to be everywhere, as were Pamela Rosenkranz’s colourful smears, and works by Albert Oehlen, Josef Albers, Alice Neel, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. I too got caught up in the enthusiasm for paint and bought a work which only later occurred to me had no way of fitting through the door of my Hong Kong apartment.

There were artists floating around in abundance this year too. I spotted Tracey Emin, and Robin Rhode, whose enthusiasm and cheeriness were a welcome panacea to our exhaustion and cynicism. The artist delightedly showed us his recent Hatje Cantz published book. ‘It’s like a weapon. It’s so heavy it can decapitate Ned Stark', he declared. Good luck getting that past security then. I chatted with designer and artist, Arik Levy who was enjoying his latest ‘French strike app, so now you can always know when there is a strike’ (every day, it seems). Hong Kong artist Samson Young came all the way from Hong Kong (as did quite a number of collectors this year… the Asians are out in full force) and was showing a politically loaded installation at Unlimited. There was Belgian installation artist Arne Quinze; Oscar Murillo; Berlin-based artist Jonathan Meese who had announced his involvement in next year’s staging of Parsifal for the Vienna Opera; and Cao Fei who was also attending the BMW cocktail where she had collaborated on a project. Perhaps of more interest than the brand’s artistic collaboration was the advertising used to promote their arts involvement. A large banner hanging over the UBS building, featuring a tiny boat stranded in the middle of the sea, asked us to ‘Join the Journey’. ‘Is that a photo of the boat refugees?’ one guest asked aghast.

Much has changed on the art world food chain it seems. Situated across from one another, Hauser & Wirth and White Cube exemplified this. The former had a large stand packed with visitors, and was manned by an ex-White Cube staffer (awkward). Overwhelmed by art and people overload and schvitzing like Fassbinder on barbiturates up a flight of stairs under my layers of woolens, I walked through the more relaxed booth of White Cube (it was a 90s redux with YBA’s aplenty). I thought I could hear the sound of crickets chirping, and… what’s that? Jay Jopling standing alone? Errr…was he just nodding a hello in my direction!?? I looked over my shoulder to see if a Mugrabi was perhaps standing behind me. There was a time the dealer would not acknowledge your presence unless you were a celebrity or had your G6 parked out the front, or were a hot 25 year-old curator (oh, wait…). Yes, plus ca change. —[O]