At the Asia Pacific Triennial, Universal Concerns Are Personal

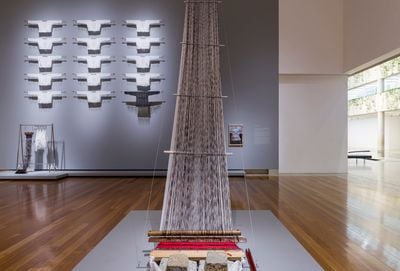

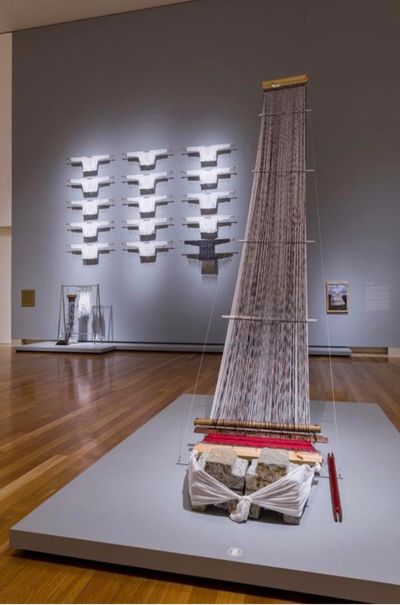

Front to back: Grace Lillian Lee and Ken Thaiday Snr, Suggoo Pennise (2021) (detail); tepo (mats) by Bajau Sama Dilaut Weavers (Purchased 2021). Exhibition view: The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane (4 December 2021–25 April 2022). Courtesy the artists. Photo: Chloë Callistemon, QAGOMA.

Since the early 1990s, the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) has reshaped the way that art from the region is presented.

APT's inception signalled a departure from the Bjelke-Petersen era in Queensland, which was defined by conservatism, cronyism, and corruption. The demise of premier Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen coincided with reforms to Australian foreign policy under Foreign Minister Gareth Evans, who in 1989 called for a 'cultural relations' approach to regional security.

Produced by a committee of curators and partner organisations throughout the Asia Pacific since its inception, APT is distinct from other recurrent international exhibition series as it operates without an overarching theme. This year's tenth edition (4 December 2021–25 April 2022) is no different.

With a curatorial team of 15 headed by QAGOMA's Tarun Nagesh, Reuben Keehan, and Ruth McDougall, 69 projects by 150 artists presented across the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art interrogate traditions and technologies, both old and new, while countering a Covid-related increase in digital reliance with an emphasis on tactility.

From the main entrance of the Queensland Art Gallery, a descent on the escalators provides a glimpse of Hairloom (2021), an installation by Rocky Cajigan, who was born in the Cordillera region of the Philippines in 1988 and hails from Fontok and Kankaney heritage.

Suspended at height is a choir of cotton shirts, typical of garments made using backstrap looms for indigenous rituals, with human hair woven in.

Evidence of weaving dates back to the second millennium BC on the archipelago, which would become the Philippines under Spanish rule during the 16th century. In keeping, a loom forms this installation's central component, secured to the ground by backstrap using piedras, building blocks used to make roads and churches in colonial times.

A poignant homage to the artist's displaced ancestors, the loom is threaded with dark brown hair collected from salons in the municipalities of La Trinidad and Bontoc, the latter where Cajigan's mother ran a souvenir shop. Warp fibres reach 12 metres towards the ceiling into an implied ancestral realm.

Where Hairloom investigates colonisation, an array of ceramic sculptures from 1973 to 2021 by Kimiyo Mishima installed in the adjacent gallery relate to global capitalism.

Working in parallel to the Japanese avantgarde group Gutai, Mishima has been meticulously replicating commercial packaging in ceramics since the 1970s. Presented on a large plinth are a selection of these replicas—including fruit boxes, paper bags, and soda cans—much of them originating from multinational corporations including Heineken, Chiquita, and Coca-Cola.

Whereas between the 16th and mid-20th century, physical force was the principal method of procuring resources including land and labour, the 20th century saw this violence extend to the economic realm. Multinational corporations created demand for foreign commodities within third world countries and also monopolised the distribution of cash crops.

Extending colonial histories into the 21st century is another ceramic artwork by Yasmin Smith, which illustrates relations with China from an Australian perspective

Flooded Rose Red Basin (2018) is a barrier-like installation slip cast at the Jinhui Ceramic Sanitary Ware Factory in Sichuan Province—'Basin' in the title references the bathroom sinks produced by the factory.

The artwork is composed of ceramic bamboo reeds with a subtle graininess, and eucalyptus branches whose translucent surfaces are disrupted by a viscous gum-ash glaze creating hairline cracks in the amber-olive colour surface.

The rose gum species of eucalyptus, encountered by the artist whilst on residency, was introduced to China by foreign diplomats during the 19th century, while the eucalyptus on the Australian five dollar note was adopted as a totem from Australia's indigenous communities.

Amid the combinations of scales, colours, materials, textures and sounds, a rhythm emerges in the exhibition that signals divergent—specific, contextual—but not divisive concerns. While copious and, at times, conflicting content can be difficult to negotiate, a poignancy results from context-specific yet relatable narratives.

Rathin Barman engages concrete to explore how the architectures of Kolkata are inhabited and change over time.

A series of Barman's small sculptures called Notes from Lived Spaces 16 (2021), which at first glance appear like small piles of pavers, and a monumental concrete rendition of a building façade titled Reconstructed Living Spaces (2021), are works that greet visitors at the main entrance to the Gallery of Modern Art.

Cool modern white brick forms are juxtaposed with red ones embossed with architectural features during the casting process.

The distinction in styles signify the culture of the occupants and the time of occupancy: like the venetian shutters on the arched window of Notes from Lived Spaces No.4, an attribute of colonial mansions built during the 19th century occupied by Bengali families.

Resembling tetris blocks, the bricks are irregular in shape, creating voids and interruptions of colour and form when stacked. These absences and intrusions convey allegories of human displacement and rapid urban development, as families are forced to leave and buildings are adapted for commercial enterprise.

Despite the geopolitical specificity of Barman's artwork, gentrification is not an isolated concern. Similar to real estate, water security is also a universal problem, as demonstrated by Alia Farid's In Lieu of What Was (2019).

Farid's installation, positioned around the corner, in the central ground floor gallery, features a set of sabils, public water fountains installed across Islamic cities. One of the five styles represented is a component of the Abraj AI-Kuwait, the World Heritage-listed set of mushroom-like monumental water towers in Kuwait, which Farid's model reduces to a height of three metres.

Farid is concerned with the high consumption of water in Kuwait, which is disproportionate to its supply in a country with 'no rivers'. This concern translates into a proposal, through the other cast renditions in this installation, increased in size to match the fountain model.

Each cast charts the development of water vessels in West Asia—from the re-usable clay hebs, earthen zamzamiyahs, and jarrah copper water pitchers to the ubiquitous, disposable and wasteful plastic bottle of today.

The form of the vessel extends to the nation state in Construction and Deconstruction 2021 (2021) by Myanmar-based performance collective 3AM.

Responding to a landslide in the state of Kachin in 2020, a catastrophe that killed more than 160 miners, many of whom were domestic migrant workers, the single-channel video is shown on a 40-inch flatscreen on the second floor installed between flights of escalators and stairs.

The video documents a studio performance involving the collective's three artists—Ma Ei, Ko Latt, and Yadanar Win—drawing coloured liquid representative of the Myanmar flag from earthen vessels and mixing it with flour.

The artists knead the dough until the red, green, and yellow segments become indiscernible: a commentary on the construction of nationhood and the erasures that occur therein, which extends to the uncoupling of peoples and statehood that unfolds across APT10.

For nearly three decades, APT exhibitions have always placed primacy in providing space for artists to reflect, reconcile, and reconstruct ideas and conditions that concern them.

APT10 continues this focus by pushing back on the resistance of some governments in the region to acknowledge diverse and complex communities that often extend beyond the borders imposed upon them. —[O]