The 14th Gwangju Biennale Repeats Planetary Themes for a Reason

Meiro Koizumi, Theater of Life (2023) (production still). Five-channel video installation. Dimensions variable. Commissioned by the 14th Gwangju Biennale and Han Nefkens Foundation. Courtesy the artist; Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam; MUJIN-TO Production, Tokyo.

At the 14th Gwangju Biennale's press conference, a local journalist probed artistic director Sook-Kyung Lee on the difference between this edition's themes and the one before it.

It wasn't a bad question. soft and weak like water (7 April–9 July 2023), which takes its title from the Tao Te Ching, explores 'our shared planet as a site of resistance, coexistence, solidarity.' Its framework echoes the 2021 Gwangju Biennale, Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning, which 'delve[d] into a broad set of cosmologies, activating planetary life-systems, queer technologies, and modes of communal survival.'

Of course, ideas of alternative, planetary globalisms have informed biennials for years, which is fine unless that repetition is read as a sign of the global art world's failure to develop solidarity beyond its representation in international exhibitions that barely connect to their contexts.

soft and weak like water seems to have pre-empted that critique by curating an impeccable show, whose relational flow is defined by an arrangement of artworks by 79 artists and collectives that feels measured to the millimetre.

Drawing on the Taoist belief that water can facilitate change across scales and speeds—from an erosive slow drip to a destructive tidal wave—the show opens in the dark, ground-level space of the Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall. There, Buhlebezwe Siwani's immersive installation An Offering (Umnikelo) (2023) forms a multicoloured forest of hanging wool ropes.

Referring to belts worn by Zion church members in Southern Africa, they cluster around a soil landscape that frames a path to The Spirits Descended (Yehla Moya) (2022). The three-channel video, where female spirits of nature move through different terrains before congregating in the sea, is projected onto two walls and a water pool between them.

From here, Seung Ae Lee's mural covering the wall lining the ramp leading to the first floor, The Wanderer (2023), draws on purification rituals for the dead found in Korean folk religions. Forms recalling forest spirits performing rites within a magical landscape were made from paper cut-outs textured with pencil rubbings on wood, stone, and soil.

This introductory pairing of works invoking animist traditions from here and elsewhere, sets the stage for the first of four chapters composing the Biennale Hall's central show, with works by Yuki Kihara, Candice Lin, Yuko Mohri, and Naeem Mohaiemen, among others, showing in four additional sites across the city, from Gwangju National Museum to the Mugaksa Buddhist temple.

'Luminous Halo' functions as a bridge between the 'spirit of Gwangju'—referring to the May 18 Democratic Movement named after the 1980 Gwangju Uprising that was violently suppressed by a military dictatorship—and 'transnational movements for democracy, justice, and equality'. The section opens with Gwangju Blooming (2023): hanging banners by Malaysian collective Pangrok Sulap, who explored woodcut printing traditions that document and memorialise the May 18 Movement.

The rose appears across images of resistance, celebration, and mourning. Scores of them are thrown to jubilant crowds in one print, while in another, a rose appears on top of each coffin. The flower seems to gesture towards a 2021 memorial organised in Gwangju by Myanmar-Gwangju Solidarity, when roses were laid to honour the victims of Myanmar's democracy protests.

From here, instances of relational encounter continue. Letters for Occasions (2023), Farah Al Qasimi's wall-spanning installation of photographs taken inside the artist's home in the U.A.E., extends towards the wall where Jiwon Yu's sculpture Terminable Destiny (2023) begins. Yu's irregular, honeycomb grid made from painted cardboard and cement covers three walls like architectural fungi, evoking the compressed view of an apartment block with its outer wall ripped off.

Such movements from realism to abstraction extend to Yeon-gyun Kang's 'Petrified Wood' series (2017–2023), where white branches form organic, grid-like networks on black grounds. The series marks a shift for Kang, whose realist drawing series 'Between Sky and Earth' (1981–ongoing) depicts the May 18 Movement—a shift that mirrors the Biennale's intentions to explore solidarity as a plateau of trans-temporal interconnections in which Gwangju is but one node.

Of course, ideas of alternative, planetary globalisms have informed biennials for years...

Larry Achiampong's Reliquary 2 (2020) creates a firm point of global resonance. The single-channel video is narrated by the artist reading a letter to his children written over the Covid-19 lockdowns. Over images of industrial coastlines across which an animated astronaut walks, Achiampong talks about pre-pandemic life, when survival was the central focus in a world that moved too fast, and life after, when governments continued to put profit before people.

Achiampong's observations recall a woodcut by Oh Yoon, a member of the 1980s Minjung art movement, which was influenced by the Gwangju Uprising. Presented among a group of the artist's works on view behind Gwangju Blooming, Donghak (1980) shows rifle-bearing peasants standing shoulder to shoulder—a reference to the 1894 Donghak Peasant Revolution that espoused equality.

Donghak responds to the issue of repetition in the recurring theme of planetary co-existence across biennials by drawing a long view. Amid centuries of ongoing systemic inequality worldwide, the struggle for equality continues.

That transnational, transhistorical mission expands in 'Luminous Halo', with installations by Christine Sun Kim and Oum Jeongsoon illuminating how art is experienced beyond sight and sound.

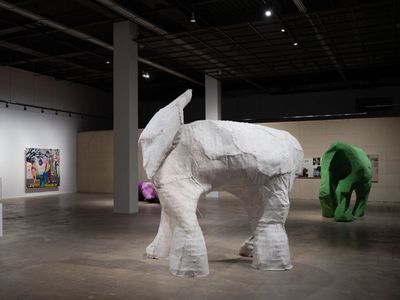

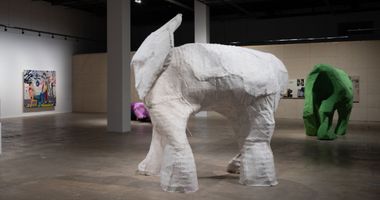

Kim's Every Life Signs (2022) projects hand signs onto the floor to articulate variations by which gestures for numbers can communicate different meanings for the hearing impaired. Oum's Elephant without Trunk (2023) presents large patchwork-covered elephant sculptures, whose forms were interpreted by the visually impaired—it was awarded the Gwangju Biennale's first Park Seo-Bo Art Prize of USD 100,000.

Indeed, while struggles for equality have endured across centuries, conceptions of equality have expanded in the present, which explains why biennials keep seeking to redefine notions of the universal in a world that has historically relegated people to violent and exclusionary hierarchies.

soft and weak like water seems to have pre-empted that critique by curating an impeccable show...

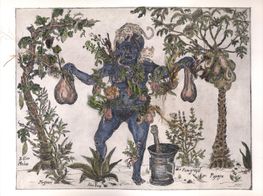

'Ancestral Voices', the next chapter, considers these realignments. It opens with Noé Martínez's Bunch 3 (Racimo 3) (2022), a circle of 11 humanoid ceramic vessels referring to the artist's 16th-century Indigenous ancestors, who were transformed into tradable objects when European colonisers trafficked them from the Huasteca region of Mexico. At the centre of the circle hangs a collection of ceramic bodies tied together with white string—as if to visualise the bondage that Martínez seeks to release his ancestors from.

This sense of inter-generational purpose connects with the acrylic-on-paper paintings lining the shelved walls bordering the installation by Aboriginal artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Kngwarreye is an Anmatyerre custodian of Dreaming sites—places of all-encompassing spiritual, historical, and cultural significance—located in the desert region of Utopia, Central Australia.

Kngwarreye, who began painting in her 70s, created lines inspired by the markings made on women's bodies with ash, ground ochre, and charcoal during Awelye, an Anmatyerre ceremony defined by matrilineal kinship, shared knowledge, and Dream-time stories. Awelye became central to the Aboriginal land rights struggle in the 1970s, which lead to the Utopia Pastoral Lease of 1979 that returned ownership of Utopia to its traditional custodians.

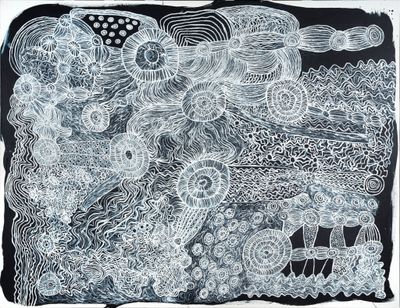

The idea that art can function as an inter-generational tool for resistance and recovery is equally expressed in paintings by Betty Muffler, a Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara artist and ngangkari, an Anangu healer.

Responding to the impact of British atomic testing in Australia in the 1950s and 60s, which killed and displaced many of Muffler's relatives, five works from the artist's painting series 'Ngangkari Ngura (Healing Country)' (2017–2020) are on view, each mapping healing sites in Muffler's home Country with white markings on black grounds.

Distilling these cross-temporal and generational connections across 'Ancestral Voices' is a central installation by the Aotearoa-based Mataaho Collective. Using traditional Māori weaving techniques, a central mat made from orange and grey ratchet tie-down straps and fasteners used to secure cargo during transport, is raised by its fastenings to three pillars and two points on the floor.

The orange refers to Parawhenuamea, the Māori embodiment of fresh water, while the grey refers to Tuakirikiri, the ancestor of gravel and small rocks. The tension created from their interweaving, the artists state, reflects their reliance on one another to create an environment. The same tension mirrors the enmeshments, both natural and man-made, that have shaped life on Earth across millennia.

All this leads to 'Transient Sovereignty' and 'Planetary Times', the two final chapters, where hybrid forms open future horizons. Yuma Taru's The Tongue of the Cloth (2021) is a hanging sculpture of four handwoven cloths, whose ribbon-like twists and curls visualise a belief among Atayal Elders, an Indigenous group in Taiwan, that 'words should be soft like cloth' and thus expressed without harm.

Yet the sculpture also reflects Taru's roots as the daughter of a Han Chinese father and Atayal mother, who began exploring Atayal culture in her late 20s and relocated to her maternal village to learn, preserve, and promote Atayal weaving traditions.

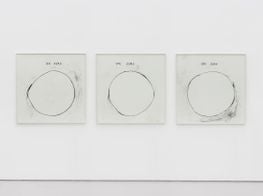

Meiro Koizumi's five-channel video projection Theater of Life (2023), which layers footage across a large corner of the hall like a new-media pediment, likewise dwells on embodied hybridity. Children of the Korean diaspora in Central Asia, who now live in Gwangju, were filmed engaging in a drama workshop exploring their place in a history that extends beyond Korea's borders.

The transcending of borders, both geographical and temporal, also informs Guadalupe Maravilla's four healing sound instruments arranged just before Koizumi's projection. Created from steel skeletons coated in a bone-like material made from microwaved fibres, each form features objects the artist collected and commissioned along his childhood migration route from El Salvador to the United States, including loofahs, stone carvings of body parts, and tools.

Reflecting their function as instruments for sound baths that fuse healing traditions from Indigenous cultures in the Americas and elsewhere, each 'Disease Thrower' (2019–ongoing) holds a gong tuned to a specific planetary frequency.

These gongs, Maravilla explains, were made in the U.S. and Germany based on data collected by NASA, making every sculpture a fusion of grounded-yet-futurist forms, as with the gong tuned to Earth for the bed-shaped Disease Thrower #11 (2021).

A return to Earth seems to be soft and weak like water's guiding proposition—an invitation that comes off as a challenge in Emilija Škarnulytė's Æqualia (2023). The monumental film, screened in a black-box room with a mirrored ceiling, follows a figure wearing a mermaid tail swimming down the blended line where the milky waters of the Rio Solimões and the black waters of the Rio Negro meet. First, the body is viewed from above as it swims. Then, the camera enters the water, where pink dolphins, whose forms recall the swimmer's suit, come into close view.

Æqualia's intimate encounter feels terrifying at first, sublime even, which is to be expected when creatures and forces that normally remain at a distance come into close contact. Maybe when such fears are overcome, the need for international exhibitions calling for planetary solidarity will subside. —[O]