Art Fair Philippines and the Manila Biennale: Between Art Fair and Bayan-ale

Kawayan de Guia, Lady Liberty (2015). Installation view: Manila Biennale: Open City, Intramuros, Manila (2 February–5 March 2018). Photo: Stephanie Bailey.

Martha Atienza's single-channel video Our Islands 11°16'58.4 N 123°45'07.0'E (2017) shows an underwater procession based on the Ati-atihan festival, which emerged during colonisation in the 16th Century, and blends animist and Catholic symbolism. Filmed in the waters of Bantayan Island, where cross-dressing and role-playing intermingle with representations of baby Jesus during festivities, the video shows costumed compressor divers moving ethereally over the seabed. Among a host of characters is Christ carrying the cross, a Typhoon Yolanda survivor, and a drug dealer with a sign commonly seen in Duterte's war on drugs: 'DRUG LORD AKO WAG TULARAN' ('Drug lord don't imitate me').

Awarded the Baloise Art Prize at Art Basel 2017, Our Islands was beautifully installed in the fountain area of Tower One and Exchange Plaza in Makati City, Metro Manila, for the '10 Days of Art' initiative (23 February–4 March 2018) spearheaded by Art Fair Philippines. One news report described the public presentation as a homecoming for a work that speaks to the current state of the Philippines, from its culture, politics and industry to its natural environment.

The video's launch on 26 February was an apt prelude to the the sixth edition of Art Fair Philippines (ArtFairPH, 1–4 March 2018). As with the Ati-atihan parade, ArtFairPH is a hybrid, homegrown affair, which reflects the country's complex and evolving identity, not to mention Metro Manila's composition as a sprawling city of cities.

ArtFairPH has been staged at The Link carpark in Makati since its 2013 launch, growing from one floor with 24 galleries in year one to six floors in 2018. For its sixth edition, three of these levels hosted 36 local galleries, including 1335 Mabini (where works by Kiri Dalena, Federico Solmi, Buen Calubayan, Mark Salvatus, Jess Aico and Pandy Aviado stood out), and 15 international spaces, such as Gajah Gallery (presenting fantastic paintings and bronze sculptures by Yunizar). ArtFairPH/Photo launched with six curated booths (plus one project and special presentation), including Mabini Projects' focus on ethnographer Eduardo Maferré, whose prints from the 1930s to 1950s of Cordillera's tribes sold out by the vernissage's end.

Dispersed throughout the fair were seven ArtFairPH/Projects, including Lyra Garcellano's two-channel video installation Tropical Loop, which challenged the image of the Philippines as a place of servitude and sun. Accompanying this was a neon sign reading 'SOUTHEAST ASIAN ARTIST / To be or not to be', which was shown as part of Garcellano's 2017 exhibition at Finale Art File, Gordion Knot, challenging the regional term as a construct reinforcing geopolitical hierarchies.

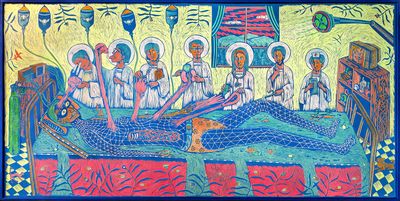

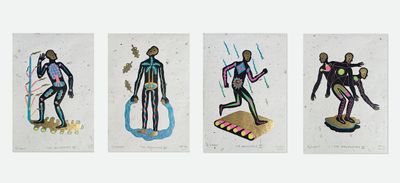

In general, depictions of Christ were everywhere, with Leonardo Aguinaldo's project booth offering the freshest approach. In one set, lines carved into large rubber sheets linocut-style create brightly coloured compositions that seem to draw equally from folk art as they do from comics. Mahal na Dasal, or Expensive Prayer (2017), shows art handlers holding Da Vinci's infamous USD 450 million Salvator Mundi; I See You (2018) depicts seven 'saints' pulling a woman's pink organs out from her body.

Paying homage to an unofficial national symbol—not unlike the crossbred Ati-atihan festival and its mix of indigenous and colonial influences—were Lara De Los Reyes' colourful knitted yarn banners at Taksu, which were arranged in a grouping that included Juni Salvador's tongue-in-cheek pop-infused 2018 collages of Very Cute Pussies. Reyes' banners emulate decorations that adorn the Jeepney: a public transport vehicle that originates from the re-purposed American military jeeps used to get around Manila after the city's cable street cars were destroyed in World War II. 'PUTANG INA' reads one, 'NANLABAN' reads another—the former, a common Tagalog swearword; the latter, a justification for drug war killings, meaning a perpetrator 'resisted' arrest or questioning.

Everyday Impunity's black-box booth was more explicit in its critique. Curated by Erwin Romulo, it re-created the scene of a shooting in Payatas of a young girl's father, an accused drug dealer, by bringing the couch where he died and the bullet that killed him into a space filled with images by Magnum Foundation grant awardee Carlo Gabuco, who has documented the drug war since it began.

Contrasts between play and dismay, fantasy and reality, figuration and abstraction, were a defining characteristic of the fair, where heavy salon-style hangs outnumbered minimal arrangements. Commenting on the deluge was Nilo Ilarde's project covering one booth floor with 24,124 small, multi-coloured die-cast cars. This site-specific vehicular tapestry plays on Douglas Huebler's 1968 quote about not wishing to add more objects to a world already filled with them, with Ilarde updating the statement with the title: The art fair is full of objects, more or less interesting; I wish to add 24,124 cars (2018).

Small assemblages by Ilarde at the artist-run MO_Space hung next to large collages by his teacher Roberto Chabet, godfather of Philippine conceptual art, in a Mariano Ching curated booth—the third edition in the gallery's exhibition series Objects, Paintings, Sculptures. Small constructions by artists such as MM Yu and Micaela Benedicto were arranged on two tables, with broke-down architectural structures by Eugene Jarque and Jiddu San Jose echoing Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan's larger cardboard house models at STPI (Dwelling, After In-Habit: Project Another Country III and III, both 2017), and Ryan Villamael's intricate paper-cut home at Silverlens (Unknown Land I, 2016).

The domestic/architectural thread continued beyond the fair at Isa Lorenzo and Rachel Rillo's new project space Calle Wright, which launched with an intervention by Heman Chong and Gary-Ross Pastrana in the former residence (Never is a Promise, 27 February–26 May 2018). Structural references expanded at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, where Flatlands (7 December 2017–4 March 2018), curated by director Joselina Cruz, considered 'constructed environments built for public housing or private homes' as sites where the contradictory processes of decolonisation and globalisation occur.

Flatlands opened with a wall of photographs of modernist structures from Africa, including Rwanda's Kigali International Airport: part of James Beckett's installation Negative Space: A Scenario Generator for Clandestine Building in Africa (2015). From here, works by Hrair Sarkissian and Eugenio Tibaldi led to Amie Siegel's Provenance (2013), which films the journey taken by Le Corbusier and Jeanneret designed furniture from European collectors' homes to their site of origin in Chandigarh, one of India's first planned cities. Provenance was screened alongside Siegel's film documenting Provenance's Christie's auction, Lot 248 (2013)—an effective pairing that articulated inherent connections between local form and an expansive, tainted, and ever-circulating market-driven globalism.

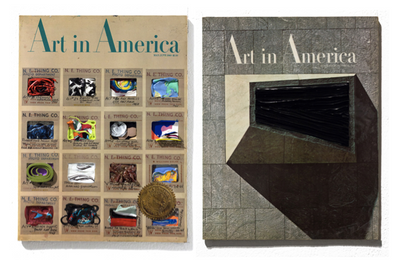

Such enmeshed local/global interrelation was expressed throughout ArtFairPH. Award-winning filmmaker Kidlat Tahimik's project installation, WW3–the Protracted Kultur War (2018), united two figures in a landscape of wooden sculpture: Inhabian, an Ifugaos deity, and Marilyn Monroe. Monica Delgado at Galleria Duemila intervened on a series of old Art in America covers with abstract expressionist flurries of acrylic paint. At Vinyl on Vinyl Gallery, where Agung Prabowo's small prints of black silhouettes with gilded skulls shone, Kobusher formalised animated characters into minimalist near-abstractions, including one canvas showing the South Park four becoming one face (Fab Four, 2018).

Colonial dialectics was the subtext of '110 Years of Filipino Artists Elsewhere', curated by Lisa Guerrero Nakpil and organised by auction house Léon Gallery with the Asian Cultural Council Manila, whose fellowship programme—which Léon supports—offers international residencies for Filipino artists. Paintings by 12 artists ranged from Miguel Zaragoza's 1887 oil on canvas study, The Presentation of the Indigenous Filipinos to the Queen Regent Maria Cristina and the Princess Mercedes of Asturias at the General Exposition of the Philippine Islands, to Filipino-American artist—and hard-edge pioneer—Leo Valledor's irregularly shaped minimalist canvases, In the A.M and Opuscope (both 1985).

Elsewhere, Salcedo Private View showed works on paper that National Artist awardee Arturo Luz made during his 1960s travels through Italy—one of the many government grants the artist, also an accomplished gallerist and museum director, received. Luz's minimalist, geometric paintings and sculptures at The Crucible Gallery included an aluminum wall piece, Black Forms on White Space (2012), which mirrors the artist's Black and White painting that lines one wall inside the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP). This extraordinary floating volume construction, built in 1969 under the Marcos regime, was designed by Leandro Valencia Locsin. Its brutalist exterior contrasts with an organically curvaceous interior, where works by National Artists—including fantastic paintings by Ang Kiukok, Romulo Olazo, and Cesar Legaspi—are installed. Temporary exhibitions featured Rene Aquitania (Walking Still, 25 January–4 March 2018), and Dex Fernandez's comic character Garapata (GC: 1, 2, 3, 3 February–4 March 2018).

A brisk walk away at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila (where Luz was the founding director), Legaspi's Bar Girls, a 1947 painting of two green-faced women who look remarkably like Tretchikoff's 1952 Chinese Girl, forms part of The Philippine Contemporary: To Scale the Past and the Possible, curated by Patrick D. Flores. This excellent permanent exhibition covers Philippine art from 1915 onward through an extensive artist list, including Evelyn Collantes, David Medalla, Lena Cobangbang, Catalina Africa, and Raymundo Albano, whose material abstractions came to mind at Brisa Amir's stunning show of terrazzo-esque works on paper, Slow Painting (15 February–10 March 2018), at Art Informal's Karrivin Plaza gallery, where works by Tosha Albor and Christina Dy were also exhibited.

At the museum, Elmer Borlongan's temporary show, An Extraordinary Eye for the Ordinary (22 January–28 March 2018), consisted of some 150 social realist paintings populated by mostly bald figures, which sometimes recall Yue Minjun's cynical canvases, albeit without the laughter.

There was a real sense of osmosis between ArtFairPH and Metro Manila's museums. Three shows at Makati's Ayala Museum included Alfonso Ossorio: A Survey 1940–1989 (27 February–17 June 2018), where thickly laden abstract expressionist works connected with canvases throughout the fair. These included Charlie Co's apocalyptic acrylic and modelling paste fever dreams at Gallery Orange and Viva Excon, where Co's portrait of a deranged Blue Suited Lone Wolf (2017) was on sale to fund this 28-year-old biennial's next edition (November 2018, Roxas City); and Ronante Maratas' manic oil and collage explosions at Ysobel Art Gallery, out of which sinister-yet-comic figures, from God Eater to Naysayer, barely emerge.

Urban Labyrinth (23 February–15 April 2018), an exhibition Ayala co-organised with Arndt Art Agency, is dominated by Rodel Tapaya's densely populated paintings of folklore-infused urban jungles; while a 2018 stop motion animation, Kalahati Dalamhati, touchingly conveys the experience of Overseas Foreign Workers and their families. (Tapaya was represented by a number of spaces at the fair, including Arndt and Soka Art Center.) Contrasting with Ossorio and Tapaya is Fernando Zóbel's permanent exhibition of minimalist drawings, prints, and paintings from the 1950s to the early 1980s, with Zóbel's work showcased by Galería Cayón at the fair. (Ayala Museum presented Zóbel's work in a collateral exhibition at the 57th Venice Biennale, some 50 years after his 1962 debut there.)

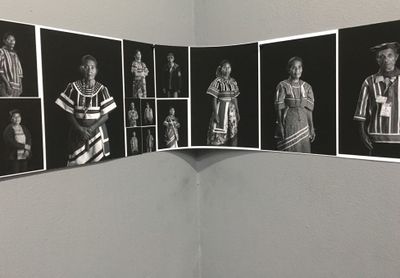

Institutional-art fair connections continued in ArtFairPH/Photo, which included Neal Oshima's project booth of photographs portraying indigenous tribes, 'Kin', and Provocations, a survey of 14 Philippine documentary photographers—from Gelay Concepcion's moving portraits of Manila's Golden Gays to Jose Enrique Soriano's 1991–1994 photographs of Metro Manila's health institutions—curated by Oshima with Angel Velasco Shaw. On loan from New York's International Center of Photography was a special exhibition of prints by street photographer Weegee, honouring a sharp and witty eye. Alongside crime scene snaps from 1930s New York, for instance, was a 1937 shot of a firetruck extinguishing a building fire, the sign 'simply add boiling water' on the structure's façade.

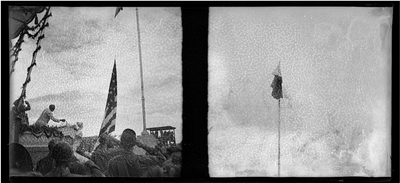

Silverlens's participation in ArtFairPH/Photo, separate from the gallery's main booth, included Wawi Navarroza's stunning print Tabula Rasa (2015), which frames a dust-covered marble-slab-holding worker from the marble-rich Romblon province like a classical Greek statue. It was positioned near 1946 prints by Teodulo Protomartir, whose negatives were discovered in 2007 by director/screenwriter Uro dela Cruz. (Silverlens staged Being There 1946: The Legacy of Teodulo Protomartir in summer 2010.) One image, Legislative Building in Ruins (No. 23C), recalls a 1945 Fernando Amorsolo painting of the same name housed at the National Museum of Fine Art, which documents the destruction of the National Museum and Library collections after the Battle of Manila that year.

Protomartir's photographs of the American flag being lowered and the Philippine flag arisen on 4 July 1946—the day the Philippines regained sovereignty—were included in Open City, the inaugural Manila Biennale (2 February–5 March 2018). Curated by Ringo Bunoan with Con Cabrera, Cocoy Lumbao and Alice Sarmiento in the walled city of Intramuros (the oldest part of Manila), this artist-run, community oriented, site-specific exhibition took the Battle of Manila as a point of departure—what executive director Carlos Celdran, himself an artist and activist, describes as the moment when 'Filipinos lost a reference to their culture'.

One work installed at Plaza Roma, a park located in front of Manila Cathedral, expands on Celdran's statement. Carina Evangelista's Liwayway ng Kalayaan: The Dawn of Freedom (2018) consists of painted billboards depicting scenes from 1944 Japanese propaganda film, The Dawn of Freedom. One shows a banner that reads 'Open City', which references the signs put up throughout Manila in December 1941 to signal the abandonment of all defense efforts weeks after the Japanese invaded. The Japanese bombed the city anyway, with Japanese and American forces finishing the job in 1945, obliterating 95 percent of Intramuros' structures—and 400 years of history—in the process.

Indeed, the re-constructed San Ignacio Church, where Protomartir's photographs were installed, was one of many casualties of the war. Recently reconstructed, the chapel hall's stark white cube shell effectively framed Roberto Chabet's silver G.I. sheets laid out on the floor from entrance to altar (onethingafteranother, 2011). This metallic monochrome was bordered by 15 photographs of acrylic lightboxes that Friar Jason Dy created with pedicab drivers from the area, who filled each box with what they deemed sacred.

As Celdran explains, the Manila Biennale was created especially for Intramuros, and locally, it has come to be known as the 'Bayan-ale'—Bayan translating loosely into 'town', 'nation', and 'community'. This communal sense was palpable in another Plaza Roma installation: Aigars Bikse's pink Soviet-style sculpture-cum-slide of a fallen soldier, Red Slide (2012), which proved popular with neighbourhood kids, despite the work's violent—and political—homage.

The balance between play and critique continued at Fort Santiago, where a significant part of the exhibition was located. National hero José Rizal was jailed here before his 1896 execution, the year the Philippine Revolution commenced, and only a few years before the Malolos Republic—the first republic in Asia—was declared in 1899, despite Spain ceding the Philippines to the U.S. a year earlier.

Rizal's footsteps to Bagumbayan are commemorated around the fort with brass plaques; just one tracing of many traumas and heroics that the Manila Biennale similarly remembers. Boni Juan's installation on the steps leading down to a dungeon cell, for instance, references his grandfather: a guerilla fighter during the Japanese occupation, who was imprisoned here. Large jars filled with water, each containing a photographic portrait, stand for those who lost their lives in these cells. Elsewhere, histories of violence were brought into the present tense with Felix Bacolor's monumental Thirty Thousand Liters (2017): 150 metal drums painted UN blue and stacked into two rows to commemorate the 'systemic industrial purging' taking place in the country today.

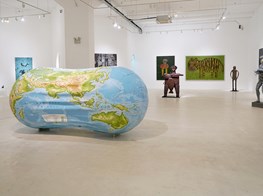

Throughout Open City, a complicated relationship between an entangled past and an equally entangled present was brought to the surface. At the very tip of Santiago Fort, Lady Liberty (2015), a monumental two-headed version of the Statue of Liberty that Kawayan de Guia made out of fibreglass, wood, and Intramuros-sourced scrap embodied this complexity. The sculpture was positioned to face Tondo, the most densely populated part of Manila known as a slum district, where the infamous former dumpsite, Smokey Mountain, is home to thousands. Coming from ArtFairPH in Makati, the financial capital of the Philippines, de Guia's double-faced liberty brought two opposite ends of a spectrum—as exemplified by Metro Manila's art fair and biennale—into stark contrast.

But that is not to say these two events—and what they represent—don't share an affinity with one another. Take Lady Liberty, which de Guia left open for viewers to vandalise, as noted in the explanatory text next to it; an assembled fusion in an ongoing process of coming together and apart. Perhaps it is at this junction that ArtFairPH and the Manila Biennale meet. —[O]