Betye Saar Transforms Objects into Art

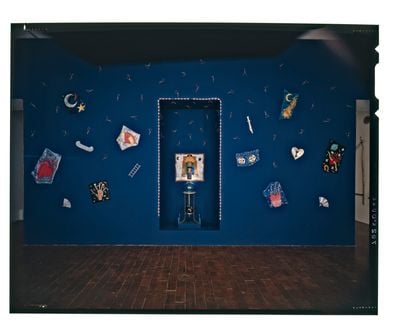

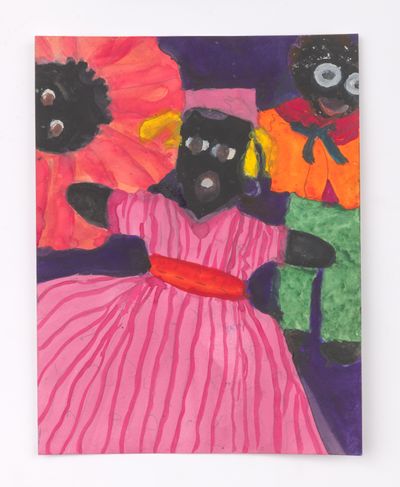

Exhibition view: Betye Saar, Black Doll Blues, Roberts Projects, Los Angeles (18 September–6 November 2021). Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects.

When Angela Davis spoke at the L.A. Museum of Contemporary Art in 2007, the activist credited Betye Saar's 1972 assemblage The Liberation of Aunt Jemima for inciting the Black women's movement.1

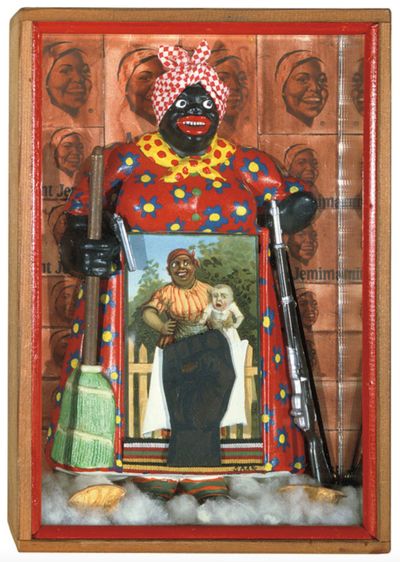

Encased in a wooden display frame stands the figure of Aunt Jemima, the brand face of American pancake syrups and mixes; a racist stereotype of a benevolent Black servant, encapsulated by the character of Mammy, played by Hattie McDaniel, in Gone with the Wind (1939).

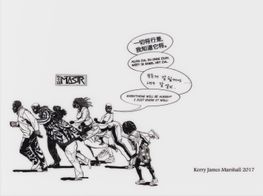

Akin to Sutapa Biswas' iconic 1985 painting of a housewife as goddess Kali in Housewives with Steak Knives—and resonating with the clear-eyed intensity of Saar's one-time student Kerry James Marshall's 2011 Portrait of Nat Turner with the Head of his Master—Saar's Jemima holds a rifle: a call to arms.

Behind her, Jemima's portrait is pasted across the box frame backing like a Warhol print, while a postcard of Jemima holding a white child rests under her bosom. Reaching up from the scene is the unequivocal gesture of a raised Black fist.

The work responds to Martin Luther King Jr's assassination in 1968, but is infused with the anger of the Watts Rebellion too, which happened in the California neighbourhood where Saar grew up.

Unable to attend marches as a mother of three, Saar channelled her rage into a sculpture whose form signalled the artist's encounter with Joseph Cornell's work—she cites him as her earliest influence—at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967.

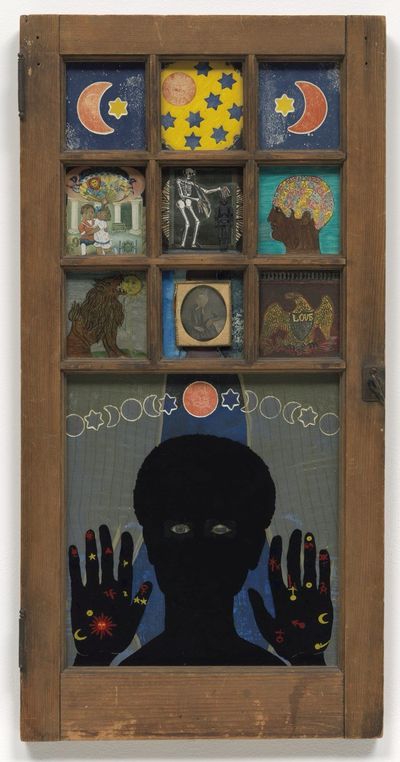

A defining moment came in 1969, when Saar departed from printmaking by installing collaged and mixed-media imagery into an old wooden window frame she found in San Bernardino. Black Girl's Window anchored Saar's 2020 exhibition at MoMA, the first examination of her printmaking, which showcased the cosmic iconography Saar would bring into three dimensions using found objects throughout her life.

Taking up the bottom half is a Black woman's silhouette with grey eyes, her hands held up with palms facing outward to reveal red and yellow astrological symbols.

Up top, nine small panes—three by three—display distinct images. Among them, Saar's cut-and-pasted paper image of a lion roaring at the sun (Saar's astrological sign is Leo), a tin-type of an Irish woman who could be Saar's grandmother, and an early 20th-century greeting card illustration of Black children dancing, representative of the artist's parents, behind whom an image of Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (1432) invokes the reverence of a medieval altarpiece.

Saar's coded symbols are as ever-present as they are evolving.

As reflected in the title of multimedia project Digital Griot (1998), referring to the role of West African storytellers, Saar's composition aligns with African storytelling traditions, among them the lukasa memory board, associated with the Central African Kingdom of Luba, in which images and materials thread registers of experience.

While 'Saar had begun to make works in old window frames in 1965, with various personal, allegorical, and political subjects', write MoMA exhibition curators Esther Adler and Christophe Cherix, Black Girl's Window was 'the first work in which she intertwined all three.'2

In one pane, a white skeleton looms over a black one: a symbolic depiction of the systemic racism that led to Saar's father's death in 1931 after he was refused entry to a segregated hospital. Saar was five, the age she lost the gift of premonition; a mystical connection her work has since charted back to.

Saar's lexicon expanded in the years after her encounter with Cornell. A trip with David Hammons to Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History in 1970 opened up the materials and aesthetics of African and Oceanic art.3

From there, resonances have stretched deep and wide. Mixed-media assemblages made from leather, bones, twigs, and beads blending Native American, Hoodoo, and Mojo aesthetics formed the artist's first solo show at California State University in 1973, which was recreated for the seminal touring exhibition of Black art, Soul of a Nation, which launched at Tate Modern in 2017.

Among these synthesised talismans was Rainbow Mojo (1972), a hanging piece tracking a shooting sun tailed by a rainbow and watched over by a universal eye.

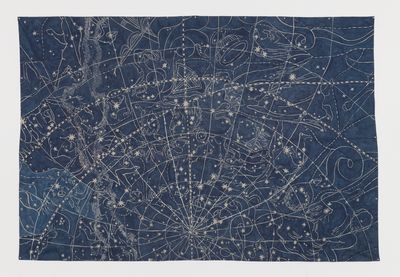

Throughout the 1970s, Saar travelled to Bali, Brazil, Haiti, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, and Senegal, weaving the cultural symbols gleaned from these trips into singular cosmological codes and combinations.

Take Shrine of Forgotten Memories (2018), a blue chest of drawers topped by a seated Buddha; or The Weight of Buddha (Contemplating Mother Wit and Street Smarts) (2014), a totemic assemblage from On the Shelf, a 2014 exhibition at Roberts Projects composed of sculptural towers made from vintage scales and figurines.

These totemic constructions speak to another influence Saar grew up around: the Watts Towers, the tallest around 30 metres high, built by Italian immigrant Simon Rodia over three decades using basic tools and street-gathered matter, including seashells.

In the 1980s, Saar began working on installations that function as expansive thought forms, like House of Fortune (1988), a table with purple candles and tarot cards surrounded by walls painted a witching-hour blue.

Apparently, each time House of Fortune is shown, plants surrounding the scene are sourced locally: in 2015, pines at De Domijnen in the Netherlands, and in 2016, tumbleweed at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Arizona. At ICA Miami, where the installation is showing in Betye Saar: Serious Moonlight (28 October 2021–17 April 2022), dried palm fronds.

Many of Saar's installations created between 1980 and 1998 on view at ICA Miami have not been shown in decades—Oasis (1984), the oldest work on view, since 1988. Twenty glass orbs circling a wicker chair lined by melted candles on a sand mound were recreated by the University of Miami's glass laboratory.

Throughout her practice, Saar has demonstrated an impressive ability to evolve, with lines of inquiry marking formal departures that grow in tandem with other material trajectories, as evidenced in a more recent work showing in Miami.

Gliding into Midnight, made in 2019, in the artist's 93rd year, is a striking monochrome sculpture: a cobalt canoe from which black hands emerge out of cobalt rocks, suspended over a floor etching of a slave ship's interior plan with figures marked out like cargo.

Woke Up This Morning, the Blues was in My Bed (2019), seems to abstract this cobalt thread further, with a panel of blue bottles arranged as if to echo the diagram, illuminated by a blue neon strip that runs along part of the canoe's interior.

These electric interventions recall Saar's 2013–2016 installation The Alpha and The Omega, a blue room with a cradle filled with glass balloons and a hanging boat frame lined with neon. Saar has long said everything begins and ends with death.

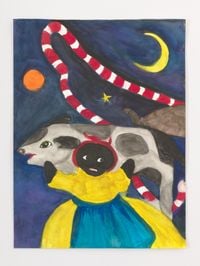

More recently, Saar presented her first exhibition of watercolours at Roberts Projects (Black Blue Dolls, 18 September–6 November 2021). Each painting depicts Black dolls from the artist's collection, started in the 1960s, a group of which sit in a rocking chair for Rock-a-bye Black Babies (2021).

'While some may view these dolls as derogatory representations of Black people, and I agree some of them are, I didn't create these paintings in the same spirit of Empowering Aunt Jemima,' Saar has said of these works. 'These paintings purely depict the Black dolls as they create the purpose of providing love and comfort.'4

Of course, Aunt Jemima hasn't disappeared from Saar's practice, nor has the artist's ongoing interrogation of racism's spiritual and physical assault. Saar's coded symbols are as ever-present as they are evolving.

In the late 1990s, Saar initiated a series of vintage washboard works with Jemima as a central protagonist—some presented alongside sketches in Call and Response, the first exhibition focusing on Saar's sketchbooks, which debuted at LACMA in 2019, before travelling to New York's Morgan Library and Museum (12 September 2020–31 January 2021) and is now showing at Nasher Sculpture Center (25 September 2021–2 January 2022).

In a striking totemic work from 2016, Heartbreak Hotel, Jemima's head sits at the crown of an art deco clock designed as a black pyramid; it featured in the artist's solo show Black White at Roberts & Tilton (now Roberts Projects), which coincided with a 2016 Fondazione Prada survey in Milan.

Black White explored the monochromatic gestures in Saar's work. Confronting assemblages like The Weight of Whiteness (2014)—a large, white, cherubic head positioned atop scales surrounded by cotton—created a striking spectrum besides four abstract paper collages from 1982: quiet monochromes marked by overlapping cream surfaces and delicate pencil lines, some wisps suggestive of body hair.

On that show, critic Jonathan Griffith observed: 'Saar has always moved back and forth between engineering explicit meanings and casting mysterious spells, between the political and the personally intuitive...'.5

Even when less direct, the artist's material reclamation speaks to a persistent redress enacted by re-assembling fragmented bodies to stand on their own.

'I consider myself an object-maker. I combine objects, materials, media and ideas to invent a new object', Saar once said. Each work an engagement with what Saar calls 'the mysterious transformation of object into art'.6 —[O]

1 UC Berkeley digital archive, 'The Liberation of Aunt Jemima', The Berkeley Revolution, https://revolution.berkeley.edu/liberation-aunt-jemima/

2 Betye Saar, 'Black Girl Window', MoMA Catalogue, eds. Esther Adler and Christophe Cherix: p.12.

3 Holland Cotter, ''It's About Time!' Betye Saar's Long Climb to the Summit', The New York Times, 13 September 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/04/arts/design/betye-saar.html

4 Betye Saar 'Black Doll Blues' Forms Latest Chapter In Her Legendary Career', Forbes, 3 September 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/chaddscott/2021/09/03/betye-saar-black-doll-blues-forms-latest-chapter-in-her-legendary-career/?sh=5dbbc8e23dcc

5 Jonathan Griffin, 'Betye Saar: Black White & Blend', ArtReview, 21 December 2016, https://artreview.com/december-2016-review-betye-saar-black-white-blend/

6 'Betye Saar: Call and Response', The Morgan Library and Museum, https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/online/betye-saar