China’s Post-Intranet Artists Get Personal

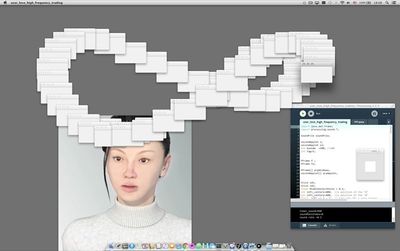

Lu Yang, Lu Yang Delusional Crime and Punishment (2016). Courtesy the artist and Société Berlin.

China's post-80s artists are no longer all that 'young', nor do they much need that moniker. With the oldest of that generation fast approaching 40, to call them young would be misleading given how rapidly many of them rose to prominence during the tail-end of China's foreign collector-powered art boom and subsequent influx of domestic collectors. These are artists who rarely needed day jobs; who signed with galleries early and have been showing in China for almost a decade. Now they're increasingly making their way into galleries, museums, collections, fairs, and publications abroad.

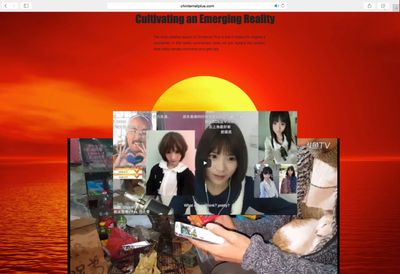

Lu Yang (b. 1984), for instance, featured on the cover of Frieze in March, Li Binyuan (b. 1985) showed at MoMa PS1 in New York last year, and Miao Ying (b. 1985) was commissioned by Manchester's Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art (CFCCA) to make new work for her Chinternet Plus project as part of a group show of six artists that runs until 12 May 2019. All three artists are also showing in a collateral project at Auckland Art Fair, which takes place from 1 to 5 May 2019.

Curated by Hutch E. Wilco and Zhang Ting for Monumental Culture, Shanghai, CHINA IMPORT DIRECT features nine post-80s Chinese artists working in digital media, who are all showing in Auckland for the first time. But while they are all new media artists, the curators have made a concerted decision to avoid a single thematic narrative. 'It's hard to put the exhibition in a box,' Wilco says, despite doing just that by housing it in a shipping container at the Fair's entrance. Figuratively, of course, he has a point. 'This new generation—with Li Binyuan, Lu Yang, and Lin Ke, for example—are not really interested in making works that are social or political in nature. The work they tend to do is more about their own personal experiences.'

This leads to art that explores very different topics. Lu is a case in point, with work combining interests in sci-fi, Buddhism, and Japanese anime in a way that's utterly individual, but nevertheless speaks to important cultural touchpoints in China and beyond. At the 12th Shanghai Biennale (10 November 2018–10 March 2019), Lu showed an installation called Material World Knight (2018), which mixed a scale model of giant aliens from Mars Attacks! attacking a city with arcade games and video projections of a robotic bunny deity.

Compare Lu's work with Wang Newone (who says she was born online in 2014), also showing in Auckland. Wang, who studied traditional Chinese painting, uses lurid colours and Daz 3D software to create lifelike human models that resemble a cross between fantasy video game avatars and virtual influencer Lil Miquela. Superficially, there are similarities, but instead of exploring the metaphysical melodramas of Otaku culture, as is the case with Lu, Wang acts more as a stylist in an entirely virtual fashion world.

It is not a shared aesthetic or political identity that distinguishes the post-80s generation of artists—nor is it the fact that they were born after China's Reform and Opening commenced in the late 1970s, or that they came of age with the internet. Artists like Zhang Huan, Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing, and Ai Weiwei were more defined by China's opening up, developing an understanding of 'Chineseness' while making art in New York during the 1990s. Feng Mengbo (b. 1966) and Cao Fei (b. 1978) pioneered post-internet art in China, making works inspired by online experiences and communities in games like Quake and Second Life. On the post-80s generation, Feng observes quite a different approach. 'I was using a computer as a toy since 1993, far before new media became popular,' he said. 'Young artists use it more as a tool.'

What's really different about this generation is that they started making art in the late 2000s, when China shut down major foreign sites such as Twitter, Facebook, Google, and YouTube in quick succession. While censorship is a major preoccupation for Miao Ying, others have been more influenced by the rich parallel digital culture that emerged on China's intranet—the portion of the internet allowed to prosper behind the Great Firewall on sites and apps like Weibo, Taobao, and Douyin. Zhu Tian (b. 1982) is one example of an artist who has excelled at using WeChat—China's most ubiquitous app—by using a group chat to auction off photos of different parts of her body in the video installation Selling the Worthless (2014). Even Miao, delighting in what she has described as 'tacky Taobao' motion graphics in her series 'LAN Love Poem.gif' (2014–2015), is just as interested in the aesthetics of the Chinese intranet as its politics.

It should be emphasised that China's post-intranet artists are hardly cut off from the outside world thanks to VPNs, and studying, working, and exhibiting abroad. They're well aware of what's happening elsewhere; it just has less resonance for them as China goes its own path, though some, like Aaajiao (b. 1984), attempt to split the difference. Aaajiao lives between Beijing and Berlin, and was among the first Chinese artists to make 3D digital graphics central to his practice, beginning with the Media Art in China show at Arario Gallery back in 2007.

Like Aaajiao, Mao Haonan (b. 1990) has embraced new software and better processing power to explore new ways of making art. In Mao's case, works are rendered in real time, with chaotic elements introduced to help communicate meditations on social complexity. The Olive Dream (2018), for instance, tracks an olive—economist Dong Fureng's metaphor for a healthy society consisting mostly of a middle class—moving through three different 3D environments.

While collectively they can be described as China's post-intranet artists (the Chinese intranet is a phenomenally pervasive part of life here), not all new media artists in China make the technology itself a major focus of their work. Several artists have continued the tradition of videoing performances that was forged by Zhang Peili and Zhang Huan, and developed by Xu Zhen and many others. Ma Qiusha (b. 1982), for instance, has made videos that document her eating cosmetics, while the Double Fly Art Center collective have taped Jackass-esque stunts, such as breaking into the Hangzhou Zoo at night and pretending to rob a bank.

On the Auckland Art Fair's CHINA IMPORT DIRECT showcase, Wilco is interested to see how New Zealanders respond to Li Binyuan's work Freedom Farming (2014), in which the artist spends two hours repeatedly throwing himself into the muddy water of a rice paddy. 'There's a lot about that work that's really couched in Chinese social culture and Chinese law—inheritance laws, land reform, and rural development.' When asked if there are works not included in this Auckland focus that he would liked to have incorporated, Wilco names Cheng Ran (b. 1981), and some of the more cinematic art made by artists, like Huang Ran (b. 1982), following in the footsteps of Yang Fudong (b. 1971).

There are other video artists and animators who would likewise have rounded out the picture, such as tragic-comic urban animations of Hong Kong's Wong Ping's (b. 1984), or the motion capture paintings by Sun Xun (b. 1981). But the fact that any group focus will inevitably have gaps is kind of the point, which returns us to Wilco's description of CHINA IMPORT DIRECT as a presentation that cannot put artists in a tight thematic box. Chinese artists are becoming more individual in their work, and this increasing diversity of approaches means it is no longer viable to ship a selection of practices abroad in a single container for easy consumption by foreign audiences.

While the Chinese intranet thrives, the economy shifts from exports to domestic consumption, and suspicion of China abroad grows, it's an important time for Chinese artists to leap the Great Firewall and share—in their myriad different ways—what's really happening inside the country's thriving art scene.

Wilco says that while New Zealanders might know the older generation of Chinese artists, few are familiar with those born after 1980, despite them starting to make inroads in Europe and the United States. That's partly due to particulars of New Zealand art history. 'If you look at the trajectory of art history in New Zealand, since the 1970s we went through that period of rediscovering who we were and our place within the Pacific, and so we started engaging with contemporary Maori art and contemporary Pacific art and to a certain extent with our relationship with Australia,' he says. 'It's really only been in the past decade or so that we've kind of become aware of the fact that our location in the world is part of the Asia Pacific.' —[O]