Christopher Le Brun: A painter of unusual seriousness

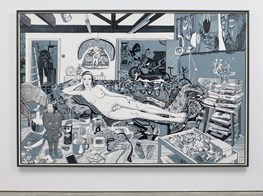

Installation view: Christopher Le Brun, Composer, Albertz Benda, New York (2 March–April 15 2017). Courtesy Albertz Benda, New York and the artist. Photo: Christopher Burke Studio.

Christopher Le Brun is president of Britain's Royal Academy of Arts. He is also a painter of unusual seriousness. His latest exhibition Composer has been curated by Zurich-based art consultant Emilie Bruner. It is held in two parts: at the Albertz Benda Gallery in New York City (until 15 Apil 2017), and at The Gallery at Windsor, Vero Beach, Florida (until 12 May 2017). Not many people will get to see both parts of the show, so it is as well that each half offers a more than satisfactory viewing experience in itself.

The exhibition prompts one to wonder whether Christopher Le Brun is an abstract painter nowadays. There are paintings where images are made difficult to read by the exuberance of his paint handling: Bax (2015) is a brushily painted view of a headland against the sea. In other paintings, images are hinted at: Pelléas (2014), the oldest painting in either half of Composer, looks very much like a lake or inlet seen from the near shore, though in a strangely distorted colour palette. There are paintings like Middle C (2015) where images appear to have been obscured by overpainting. Most of the paintings, however, appear to be entirely abstract.

Le Brun insists that this is not the point. 'The distinction between figuration and abstraction is a false one', he maintains, because human perception instinctively looks for images, so that 'in all abstract painting—even in a Barnett Newman—one's psychology seeks out recognition'. On the other hand, he does not try to pretend that figuration and abstraction are the same thing. Rather, he says that 'the balance between the two things is too fruitful to resolve'.

One of the most remarkable paintings in either New York or Florida is the diptych Goldengrove (2015–16), which might vaguely suggest autumn foliage to some spectators. It stands almost nine feet high, and is hung on the end wall of the long final room of the Albertz Benda Gallery. Like many of the works in Composer, much of the picture is filled with repeated vertical strokes of paint, ranged in untidy rows across its surface. The glowing colour is what impresses first of all. The dominant range stretches from pale cream through yellows to deep reddish-oranges, and includes everything from the very English-looking colour of custard powder, through pale and dark mustards, to very un-English suggestions of ripe papaya, mango, and other tropical fruits. Underneath the picture's top surface are marks in sky blue and various greens from mint through to a rather muddy grass.

Just as in a number of other paintings here, the density of Le Brun's markmaking eases up within a couple of inches of the canvas edge, and the lower edges of the two canvases make it obvious that Goldengrove did not start out as a diptych. Underneath the top layer of paint on the right hand canvas, there was clearly a stage when very fluid paint was allowed to drip in narrow rivulets to the bottom edge. This evidence is absent from the other canvas.

This is significant because the history of each of Le Brun's paintings is crucial. He talks of 'treating every mark as a moment', so that the finished work is an accumulation of such moments. This is not because he sees the painting process as a cathartic outpouring of feelings. In fact he is rather dismissive of the significance of such feelings. 'How you feel about the world on any particular day might just be wrong', he says. Instead, if his paint marks are to have authenticity (and thus value), then this most erudite of artists relies not upon psychology or intelligence, but upon the physical process of manipulating paint. 'The physical is the element whereby you're more likely to get some authenticity', he says. 'It's no different to swimming. You don't think about swimming, you just get on with it'. If a painting has this 'physical authenticity', then he insists that 'painting will demonstrate the truth of yourself, not just in a mental sense, but in your being'.

If a painting is conceived as an accumulation of charged moments, then the idea that it might parallel musical composition—which is implied by one interpretation of the exhibition's title—makes sense. Le Brun repeatedly uses musical terms and references as titles for his paintings. As well as those already cited, there are paintings here called Score, Note, and Symphony (all dated 2016). But he is also fond of literary references (the subtitle of Strand (Thus the light rains, thus pours) (2016) is taken from Ezra Pound), and of course in another sense 'composing' is something that any artist does. Le Brun is not merely persuaded of the similarities between the pictorial and musical arts, in other words, he sees all artists of significance as pursuing a similar imaginative ambition.

This reveals the broad romantic streak that runs through Le Brun's artistic intelligence. Recalling the beginnings of his career he says, 'I sensed in the general culture of northwest Europe a sort of imaginative romanticism that wasn't reflected in any contemporary art that I could see'. So instead he turned to the great artists of British painting. 'If you look at Turner or Blake, you see running through them a powerful visionary impulse to make a world of your own'.

This is what Christopher Le Brun attempts. These are paintings of the utmost seriousness and the highest ambition. As such they are unlike much of the art that we see nowadays, though perhaps they are appropriate for the artist who heads an institution that will celebrate its 250th anniversary next year. They are not about truth to experience. ('That just strikes me as wrong', he says.) They are not ironic. ('I think irony has a very short shelf life. The battery starts to run down almost as soon as you invoke it'.) Instead they are a sincere attempt to create something that has not existed in the world before, and which might thus stand alongside the great art of the past. 'That sounds like a rather grand ambition', Le Brun concludes, 'but it struck me that that's what art feels like'.—[O]

[All quotations are taken from a public conversation between the artist and Tim Marlow, artistic director of the Royal Academy, at The Gallery at Windsor, 24 February 2017.]