A Feminist Detour at Guangdong Times Museum

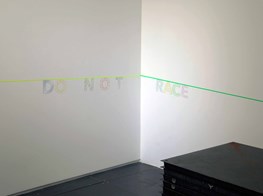

Aki Sasamoto, Do Nut Diagram (2018). Exhibition view: Forget Sorrow Grass: An Archaeology of Feminine Time, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou (14 September–17 November 2019). Courtesy Guangdong Times Museum.

We might consider the exhibition space a domestic one at Guangdong Times Museum, whose exhibition hall has been converted into open spaces, chambers, passageways, and labyrinths for its current show, Forget Sorrow Grass: An Archaeology of Feminine Time (14 September–17 November 2019). Featuring 26 works by a group of 14 artists, including Doreen Chan, Jes Fan, and Zhang Xiaogang.

The exhibition's title refers to the fragile 'forget sorrow grass'—the Chinese name for the common orange daylily, which curators Wu Jianru and Zhang Sirui describe as an online profile name for femmes who 'rely on individual agency to process and ultimately forget the pain inflicted onto them.'

The exhibition's subtitle lays out a methodology through which to explore this 'feminine' condition. 'Archaeology' implies an excavation of historical narratives lost in the passage of time, with societies and civilisations understood through the artefacts that are uncovered amidst chronological layers. In keeping, feminine time—as measured by the relegation of bodies to the domestic space—is examined across broader contexts, including patriarchal time.

Christopher K. Ho's installation Blobfish (2019), for instance, consists of a huge carpet showing a giant, distorted print of a baby's face, with an enlarged flesh-like silicone sculpture of a blobfish positioned next to it—a creature which has adapted to the pressure of the deep sea by developing gelatinous flesh and soft bones. Completing this grouping is a blown-glass tear-catcher and a set of imperial measuring rulers for the English foot resting on a pink pedestal. As the legend goes, King Henry I of England standardised the dimension of foot—a unit of measurement still widely used—from the length of his outstretched forearm.

One of the notable features in the show is the absence of the body. The radicalism of feminist art characterised by works using the body to address patriarchal violence has been eschewed to foreground invisible household labour, personal stories, and family relations. Zhang Xiaogang's oil and fibreglass on stainless-steel painting Pine & Medicine Bottle (2010) shows a table in one room of the artist's parents' house, on which sits a potted bonsai, a symbol of vitality, and scattered medicine bottles. Peng Yi-Hsuan's video Good Luck (2019) captures the moment after Peng's mother placed an ornament with small glazed tangerines, a feng shui item expected to bring good fortune, on the table—the fruit still quivering.

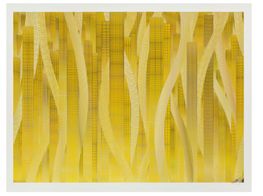

Ma Qiusha's photographic series '"Story of Space" My Grandmother's Living Room' (2007–2008) renders items in her grandmother's bedroom into a composition mirroring a floor plan, meticulously exposing personal items contained within a private domain. Inside becomes outside: a division the artist also explores in Fog No.9 (2012), a watercolour on paper tracing the translucent lace window screen that marks flimsy boundaries among Hutong and low-rise flats in Beijing.

Patty Chang's Letdown (Milk) (2017) is another study on spatial division, with multiple plywood panels serving as a hindrance to a panoramic view. The panels display a series of photographs taken by Chang during a trip to the Aral Sea, which is currently shrinking. Having just given birth, Chang's daily ritual of pumping is captured in some images depicting containers with the resulting breast milk. In these shots, Chang's maternal body and its product become the filter and measure of the landscape, with the discarded breast milk embodying the disappointment and deprivation that Chang experienced on this trip when it came to her agency. The political situation in Uzbekistan made filming—the artist's intention—almost impossible.

Political histories and contexts seep out of videos tucked away in corners and rooms, which are anchored to individual stories. In a chamber partitioned by a curtain, films by Wang Tuo create narratives based on well-known fictions. Meditation on Disappointing Reading (2016) uses Pearl S. Buck's un-translated novel about the Cultural Revolution, Three Daughters of Madame Liang (1969), as a backdrop. Two women, one reading aloud the novel translated into Chinese via software and the other cooking silently, play the roles of mother and daughter who exist in the same space seemingly oblivious of one another. Symptomatic Silence of Complicit Forgetting (2019) departs from the ending of Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House. When the protagonist, Nora, leaves the house, she proceeds to explore her existence in the dreams or memories of a male writer, images of the Red Guard interwoven with her fading representation.

Hsu Che-Yu's animated video No News From Home (2016) mixes home video, voiceover, and animation to trace the life story of the artist's 37-year-old brother, illustrating how he was involved in drugs, fights, and illegal transactions at a young age before entering into marriage—a struggle that mirrors the clashes of values in Taiwanese society after the lifting of martial law in 1987.

In other parts of the exhibition, space is converted into highly decorative sets in order to project futurist landscapes. Ad Minoliti's Froggy (2019) recalls part of a kid's room. One of the walls depicts a frog-like form painted in vibrant green, with two giant dices stacked on top of one another positioned in front of it. Each side of the dice is printed with childlike, cyborg scenes in which animal, feminist, and queer identities blend together—scenarios influenced by the writings of Donna Harroway and Judith Butler.

In one room, museum windows recalling stained glass in churches showcase a post-Anthropocene landscape with printed images depicting android "Keana-35®" in poses evocative of Kwan Yin. Keana and Wonderful Lives (1-3) (2019) by Zijie is part of a project exploring future for domestic androids in Hong Kong—a reflection on the limited rights of the city's domestic workers, the ongoing evolution of automation, and how androids might rewrite domesticity in the age of the smart home. According to the detailed manual provided by Zijie and Yunyu 'Ayo' Shih, the android is able to read and process domestic data, fully integrated into domestic and even sexual life.

As people move between private and public space, often becoming objectified in the process, so objects oscillate between mass-produced commercial goods and symbols of identity and personal belonging. In the series 'Person' (2019), Rose Salane profiles owners of lost rings found throughout the New York City Subway with the aid of an intuitive reader, a bio lab, and a pawnshop—the objects are framed and lined on the wall like archaeological specimens. Cécile B. Evans's video How Happy a Thing Can Be (2015) imbues computer-generated objects with life, showing a pair of scissors, a comb, and a screwdriver travelling from a bathroom as two women casually discuss random topics, from death to the weather, in the voiceover. As the dialogue proceeds, the objects start to bleed and scream in distress; their emotions gradually escalating from boredom to hysteria.

Like this exhibition, How Happy a Thing Can Be moves between reality and fantasy, often bringing both re together in schizophrenic proximity. Similarly, Aki Sasamoto's video Do Nut Diagram (2018), portrays a sequence of routine behaviours—including breaking, scrubbing, and scouring glass sheets in a forest—with a frenetic sense of haunting and alienating unease. Both works respond to the way time has been measured in this exhibition in sensual, mundane, and repetitive terms, often tipping over into the uncanny.

On the exterior wall of Sasamoto's video room, a poem by the artist echoes the atmosphere that the curators have conjured:

Ghosts wander about in the kitchen and bedrooms, fueled by grudge.

They roll your vegetables off a cutting board and crumple your duvet inside its sack.They dwell in the space of routines,

Trying to distract the myopic livings from seeming productivity.

Mindless domesticity recalls the time when they were alive, avoiding.

The domestic space is filled with phantoms that interfere with perceptions of daily life, as expressed with artworks that have materialised deep and complex experiences and perspectives. Yet a strong thesis on what feminine—or feminist—time is within this archaeology seems insufficient; perhaps indicative of the curators' efforts to detour from overt political utterances given the censoring of feminist and LGBT content in China in recent years.—[O]