I Taste the Future: Lofoten International Arts Festival 2017

Lofoten. Photo: Kjell Ove Storvik/NNKS.

'We are all lichens'. Famously associated with the thinking of feminist theorist Donna Haraway, this declaration—referring to a fungus that grows from algae and cyanobacteria—provided a compelling key to the 2017 Lofoten International Arts Festival (LIAF), I Taste the Future (1 September–1 October 2017), curated by Heidi Ballet and Milena Hoegsberg. Calling to mind humanity as an organism growing on the terrestrial surface as we alter its nature in codependent symbiosis, the phrase featured in Fabrizio Terranova's documentary portrait Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival (2016), a curious yet central work in the exhibition as a whole.

The subtitle of the film resonates with the show's reflections on current reality and whimsical speculations on the future. Haraway's affable account of her personal and conceptual constellations—including her relationship with her canine companion as a conduit to the nature of nature—tied together the narrative threads presented throughout LIAF 2017 in videos, sculptures, drawings and performances created by 19 artists and collectives, as well as archives detailing facts about environmental destruction and selected science-fiction classics (even Dr. Seuss's The Lorax). These were presented in four historic buildings, a sports stadium, and the streets of the fishing village Henningsvær, population 460, in Norway's Lofoten islands.

I Taste the Future considers Lofoten as a terrain exemplifying the tension between the local and global, the dynamics of capitalism and climate change, and not least of all, our impending environmental demise and/or mutation. Thus, Elin Már Øyen Vister's audio walk and sensory tour Dear Henningsvær and the Ocean that Embraces You! (2017) encouraged a deeper, nonverbal communion with Lofoten's landscape through focused listening accompanied by accounts of buried territorial histories, both literal and tendentious. Standing on a rocky outcrop overlooking the sea, slam poet-singer Ingvild Austgulen (aka Nuorta) performed a fusion of Sámi joik and Norwegian folk song as part of Vister's walk, describing one of the sounds that can only be heard if you put your ear to the ground: the seismic mapping blasts that have been disrupting undersea life forms for the past 20 years. Vister recounted how the first settlers, the sea Sámi, navigated the area for millennia yet their presence does not figure in official readings of history. 'When we are thinking about the future we have to think about the past and present together', she explained.

The sleek, minimal lines of Silje Figenschou Thoresen's drawings, included in the installation Vandret linje II (2017) and displayed in the Nordbrygga—a building that has evolved from a cod-liver oil factory to an adventure tour agency—portray the present distortion of the past that Vister references. Abstractions of archaeological drawings created by Danish archaeologist Povl Simonsen evidence the Sámi as the first inhabitants of large expanses of Northern Norway; most notably those richest in mineral deposits, such as Kvalsund, where mining will soon disrupt native reindeer breeding grounds. The government recently authorised dumping of the resulting toxic waste in the adjacent Repparfjord—about two million tons annually, including large amounts of heavy metals, into vital fish spawning waters. Dependent on the land for sustenance, the nomadic community has been forced into poverty, its livelihood destroyed by corporate interests exploiting ancestral lands; splintered by the borders of four nations, its culture has been destroyed by strident assimilation programmes.

The Sámi predicament is emblematic of just how far modern society has wandered from a mutually beneficial relationship with the planet in its crusade for economic power. As a place, Lofoten embodies this exploitative equation: protected until now by its geographic inaccessibility, the archipelago is being invaded by mass tourism and under imminent threat of oil exploration, which will destroy the fishing industry on which it depends. The tourists, drawn by the pristine remoteness, will eventually be repelled by the consequences of their own numbers. So while the picturesque façades of the quaint village are being polished by tourism dollars, they conceal the smell of a rotting future in which global corporations will ravage the community along with its way of life.

In the next room, Siri Hermansen's video Sorry (2016) tracks Norway's failure of the Sámi people, from King Harald's disingenuous address to the Sámi parliament ('Today we must express regret for the injustice the Norwegian state has previously committed against the Sámi people') to a TV clip portraying the Sámi as naive happy-go-lucky natives, framed by an interview with the patrician first president of the Sameting, Ole Henrik Magga, dressed in traditional costume. As a housemaid passes in the background holding a tray, he concludes placidly: 'The past is something that we can't undo. So a process that involves forgiveness or absolution, or questions related to that, is above all a statement of intent that one will do better than one managed to do in the past.' In short, things do not look very promising.

Exoticisation of indigenous peoples and other strangers serves the ends of economic interests together with colonialist narratives that erase rights to territorial claims. Screening on the ground floor of the Nordbrygga, Ho Tzu Nyen's The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia (2012–17), its title adopting the reductive regional appellation coined by the American military, recites a mesmerising colonial alphabet comprised of words and images chosen continuously, and randomly, from the internet by an algorithm so that no two viewings are identical. The entry 'N for narcosis, N for narration, N for nation' includes: 'Things have names only for us to better grasp them as if the blank spaces in the atlas of our minds must disappear so that the colonial empire of the mind may grow.' People need to give names to things; there seems to be no other way to communicate. Yet cultural diversity gives rise to nuances of expression that shroud our commonalities. As Haraway notes in Terranova's film, language is a mechanism of control, and the only truth lies in the failure to give a name.

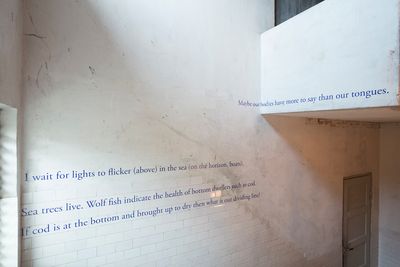

'Taste' as a description of the way we sense the world, as the exhibition title suggests, is as adequate or inadequate as any other linguistic term. This conundrum was invoked on the stairs of the former industrial building Trevarefabrikken, in one of the various blue inscriptions comprising Youmna Chlala's How Many Tongues Does It Take to Make a Color? (2017): 'Maybe our bodies read more than our tongues.' The abandoned woodcutting machinery on the dark second floor of the building—which was used for a range of commercial activities, from shrimp peeling to carpentry—conjured a steam-punk milieu suitable for Ann Lislegaard's Malstrommen (2017), a two-channel 3D animation retelling Edgar Alan Poe's 1841 tale set in Lofoten that eerily illuminated the far corner. The artist casts herself as a glabrous cyborg caught in a timeless vortex at the interstices of past and future, describing contact with an aquatic creature that evoked a blissful state of 'mirroring without surrendering to the other'. The fragmented robotic voice alludes to language as an alien possession as much as the inability to clearly convey any experience: 'Never shall I forget the sensation of language plunging into my body. It felt as if it was placed into my mind like an outside force.'

Performer Stine Janvin Motland's hypnotic, otherworldly incantation as Joan of Arc in choreographer Adam Linder's To Gear a Joan (2017) advises militant vigilance with regards to what lies in wait: 'And you ask why the future cannot be tasted? 'Cause to blink in the present has left more wasted.' Dressed in sexy, androgynous armour merging medieval and futuristic sensibilities, Motland wandered the spaces of the Trevarefabrikken, infusing each room with a solemn hush. 'Young Joans all around have their ears to the ground', she continued, harking back to Vistor's call for awareness of how we are endangering our environment in ways not yet visible. As Haraway concludes in Terranova's film about her: 'The only possible thing to do in the world is to revolt.' It is not too late to change the narrative, she posits hopefully.

Yet the revolution may be evolution, in the form of interspecies symbiosis, as Haraway recounts in her sci-fi tale of a utopian future at the conclusion of 'Story Telling for Earthly Survival'. We will evolve as hybrid holobionts that physically incorporate attributes of other species as well as machines—in the case of her character, whiskers of butterfly antennae—for optimum ecological survival and coexistence in new types of communal units. Thus, the other would actually be part of us, dissolving biological boundaries and perhaps even the need for verbal language. As such, we will physically manifest the actuality of our interdependence on other species. This will not of course be a holus-bolus transformation but a slow and sensual, often painful, series of jolts and forced alterations.

Symbiosis as a naturally occurring mechanism of survival and resistance is portrayed vividly in Lisa Rave's film Europium (2014), screening in the Fredriksenbruket, a former fish-processing factory. It considers the trajectory of colonialism and resource extraction via the evolution of the nautilus shell, sacred to the Papuans and stringed together to be used as local currency, called tabu. The creature that inhabits the shell incorporates its environment as an intrinsic part of its organism, now including the plastic that pervades its ocean habitats. Mined from the floor of the Bismarck Sea, europium, or rare earth, emits a phosphorescent glow from the forms of deep-sea shellfish and also happens to be embedded in European banknotes as authentication—bringing us full circle to the present predicament, as reflected in the form of the nautilus.

A screening of Lili Reynaud-Dewar's Teeth, Gums, Machines, Future, Society (TGMFS), on the floor below, articulated this predicament in other terms. A fragmentary, inconclusive satire of Haraway's 'Cyborg Manifesto', it follows a motley group of people in Memphis outfitted with metal dental grills talking about civil rights, comedy and the unfunny nature of truth, and the duplicity of words and their use as weapons. Every conclusion in these conversations leads to more questions, ending with the comical concern: 'Do cyborgs masturbate?'. The incoherence of the film's narrative structure perhaps reflects our inability to process the cacophony of information flying around us—a glut that has left us without the language to express what is really at stake in the present moment.

Words are rarely more articulate than the spectacles of nature. Take the aurora borealis, whose fickle green tendrils shooting and swirling across the sky—merely the random dynamics of magnetic fields and explosions of the sun—seemed to be the numinous emanations of an alien culture trying to communicate with us during our visit. Lofoten is the sort of place where silence is palpable and every sound resounds, a whoosh of wind, warbling magpies, car tires treading on tarmac. As artist Pedro Gómez-Egaña told me, 'It is as if all of the landscapes of the world have imploded'. This evocative context galvanized the curatorial framework of LIAF 2017, which engaged successfully with the locale in a profound yet compact contemplation of urgent global issues.

Dominated by film projections and performance, the show was as ephemeral as the stories it proposed as points of departure in pondering possible futures. It required visitors to slow down and spend time in the place to consider not only the fleeting propositions made by the artworks but also the world surrounding them. Hidden in plain sight among other seafaring implements hanging from a fisherman's line was an orange buoy inscribed by Chlala: 'The blue screen is not the final frontier'. It hints at where we can find the empowerment to narrate our own future if we know where to look. —[O]