In a Year of No Future: Cyberpunk at Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun

Shinro Ohtake, MON CHERI: A Self-Portrait as a Scrapped Shed (2012). Mixed media, timber, electronics, sound, steam. Dimensions variable. Exhibition view: Phantom Plane, Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future, Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong (5 October 2019–4 January 2020). Courtesy the artist and Tai Kwun Contemporary.

In what was reportedly Tokyo's cloudiest summer in over a century this July, Yoshiji Kigami, key animator of the cyberpunk classic Akira (1988), died in an arson attack that killed 35 people at Kyoto Animation. The attacker lit the fire with a lighter after dousing the studio with gasoline. 'They are always stealing', he explained in the belief the studio had taken ideas from a draft novel he sent them.

About one month earlier, on 16 June, nearly two million people took to Hong Kong's streets to challenge a bill that would have allowed the special administrative region to honour extradition requests from countries it has no extradition treaties with, including China, which has been sovereign over the city since 1997. Police refusal to approve public gatherings has made it increasingly difficult to mobilise peacefully, and Hong Kong's universities are now at the centre of the revolt, which aims to 'blossom everywhere'. To quote Joshua Clover, 'surplus danger, surplus information (...), surplus emotion' characterise this year of no future.

Theorists of techno-orientalism assert that Japan and China are 'screens' for the projection of both 'technological fantasies' and the fear of being 'colonised, mechanised and instrumentalised.' For some, self-orientalisation is empowering; for others it is all about market gain. For the curators of group show Phantom Plane, Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future at Tai Kwun Contemporary (5 October 2019–4 January 2020), it appears self-orientalism is tactical. This Hong Kong-based exploration of 'cyberpunk'—the 'snappy label' that writer William Gibson accused of depoliticising dissidence in the science-fiction subgenre—feels excellently executed if perplexingly cynical. Works by 21 artists spanning three floors of this colonial-era prison turned heritage-and-arts-complex eagerly feed the techno-orientalist frenzy that the show plays at interrogating.

Throughout, a chain of associations evokes a melancholic present future in which aesthetic pleasure is gained from loss and terror. It is in the vertigo of Hiroki Tsukuda's hi-tech iterations of Piranesi's baroque prison fictions (NEON DEMON, 2019); in Lee Bul's After Bruno Taut (Beware the sweetness of things) (2007), a chandelier of crystal, glass, acrylic beads, PVC, aluminium, copper mesh, and steel, which longs after modernist Bruno Taut's Alpine visions; and, in Tetsuya Ishida's painted scenes of microscopes anthropomorphised as bureaucrats (Interview, 1998).

Inkjet prints by Hong Kong photographer Chan Wai Kwong (Untitled 2013-2019, 2013–2019) paper a stairwell that promises escape, but provides no release. Images from Hong Kong neighbourhoods include a rat leaping; a long wet ponytail cut from the head of its owner lying abandoned; a mannequin with a gun pointed to its head. Kwong tagged his work with the protest mantra 'Add Oil!' at the exhibition's opening—under the purple light, red stamps and pink marker become just another formal element.

The exhibition's curation (by Lauren Cornell, Dawn Chan, Xue Tan and Tobias Berger, with Jeppe Ugelvig)—object-oriented, balanced in presentation of mediums, and evocative in interactions it stages among works—is disquietingly thoughtful yet vacuous. The urge to 'consider', 'reflect', and 'question', as articulated in a pamphlet foreword, feels like a taunt. The show opens with a similar tone: blinking green ACSII characters on a box-monitor describe a virtual world of 'slits' and 'grates' where 'listening' and 'examining' never reveal anything 'out of the ordinary'. Seth Price's video Romance (2003) documents player progress through the mainframe text-game Colossal Cave Adventure (1975–1977); commands typed by the artist test the game's refusal to allow contemplative or evasive moves.

Another video by Price—Rejected or Unused Clips. Arranged in Order of Importance (2003)—ends the show on the third floor with home videos of family moments and fist fights, and an extended found sequence of Taser training. Price's voice-over is difficult to hear through the whir of eight hologram LED fans in collaborative duo Zheng Mahler's The Master Algorithm (2019). Slicing menacingly through the air, the fans conjure the image of China's first Artificial Intelligence newsreader, Qiu Hao, into the gallery as a space-traveller outfitted in an elaborate flight-suit—the agent of a new Red Scare fostering a futurist Yellow Peril.

The suppression of any intelligible voices by a mix of sounds from various works glitching, pounding, and crackling over haunting tunes, seems an intended effect. We cannot hear ourselves think, let alone speak. Voices trying to communicate serve the soundscape but not the messages they want to relay.

The gallery's iconic spiral staircase leads through the show's spectral portals, all nested like an infinite mise-en-abyme. Zheng Mahler's Nostalgia Machines (2019) is a wall-size projection of a 3D-animated film around a doorway—its purple-orange cityscape flooded by rising water levels spins under the glowing eye of a corporate logo and provides access to the first floor. This cinematic gateway frames Tishan Hsu's blistering esophageal reliefs (Terrain, 1985; No Name, 1986; Stripped Nude, 1984), which give way to Jon Rafman's chatroom-led meander through live-action and found footage of Hong Kong and Istanbul (Neon Parallel 1996, 2015). Between images of mask-jewellery crafted to evade facial recognition software and a leaping beetle-like military craft, the viewer is both pursued and in pursuit through the city streets of the Mediterranean and the Pearl River Delta.

On the second floor, a timeline created by the curators begins with 960 and ends with 2046, the year before 'the capitalist system and way of life' protected by Hong Kong's Basic Law, is set to expire. The earlier Song Dynasty date marks the founding off a fort for the trade post that became Kowloon Walled City in the 20th century, a city within the city of Hong Kong, whose 30,000 inhabitants were both outside the rule of the British colonial regime and beyond Chinese control. Between 1987 and 1995, residents were resettled and the city demolished, replaced by a Qing-style garden; the story that some inhabitants preferred suicide to resettlement still circulates.

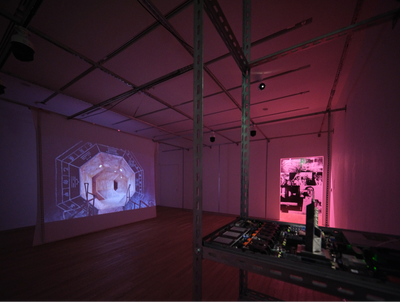

In Yuri Pattison's Tai Kwun commission False Memory (2019), video footage fluidly moves through a replica of the Walled City at Japan's Kawasaki Warehouse arcade, edited with night scenes of abandoned Hong Kong villages and footage of a semiconductor in fabrication. Projected onto a roll of tracing paper fixed to a steel-shelving frame, surveillance cameras in the room periodically project images of unsuspecting viewers. In one corner of the installation, an open computer unit with exposed transistors and drives is topped with souvenir models of Norman Foster's Hong Kong Shanghai Bank building (1985) and I.M. Pei's Bank of China (1990).

Located on the other end of the curatorial timeline is artist-writer Ho Rui An's video Student Bodies (2019), which deepens the history of neoliberalism by starting not with Mont Pelerin and the Chicago School, but with Japan's Meiji Restoration. Beginning with original footage of the now abandoned Hashima Island, whose undersea coal mines fuelled Japan's industrial rise, titles introduce the late 19th-century mission of Japanese students sent to study in the west to use its knowledge against it.

In the final sequence, a music video of Taiwanese boy band F4 singing Elvis Presley's Can't Help Falling in Love (1961) is spliced with cuts from the popular Japanese horror film that became a Hollywood remake, The Ring (1998/2002)—a figure masked by a mass of long dark hair crawls out of a television screen. 'If you look far enough east', reads a subtitle to Margaret Thatcher's digitally distorted voice, 'you always come to the west.' Ho's video asserts the opposite.

In Akira—featured in a section of the show dedicated to its cyberpunk sources—2019 is the year of the future, 31 years after an atomic explosion in Tokyo begins World War Three. Returning to present, a gallery attendant told me that Japanese interactive artist Seiko Mikami's The World Memorable: Suitcases (1993), a plastic suitcase filled with various kinds of waste, registered levels of radioactivity too high for display—the suitcase is present in the show as disruptive potential foreclosed, labelled to inform us of its withdrawal. The signal jammer in Aria Dean's Dead Zone (copy) (2019) is likewise disabled.

Among the books of cultural references offered for perusing near an original film poster for Akira, is architect Christopher Alexander's Notes on the Synthesis of Form (1964) in which the controversial design theorist argues for the 'ability to deal with several layers of form-context boundaries in concert' or rather, 'effortless contact' and 'frictionless coexistence.' The way out of the exhibition, punctuated by encounters with Hong Kong artist Nadim Abbas' Fake Present Eons (After Posenenske, 2019), is one affirmation of this approach. Titled after an anagram of 'After Posenenske,' the modules of artist Charlotte Posenenske's conduit-like participatory sculptures (recently on view across the harbour at the M+ Pavilion) have been opened into a sprawling shelter. At the opening, performers in white masks, grey sweatsuits, and slippers sat shielded by the structures. Outside, police fired charging yet unarmed protestors at close range.

Though a broken seat on the ready-made cycling station in Sondra Perry's Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016) prevented me from pedaling as the artist intended, the words mouthed by an avatar on the bike's three-screen display were unabating as I left Tai Kwun's prison yard for Hong Kong's streets. Questioning the viewer on issues of race and the 'imperialist thievery of the west's cultural imperialism,' the avatar observes, 'you are in a gallery'. Though she does not presume complicity she implies as much by asking 'how does your body feel inside of us?', as if demanding to know what I'm doing in the museum.

—[O]