Lagos Biennial 2019: Stories from Africa’s most Populous City

Temitayo Ogunbiyi, You Will Find Playgrounds Among Palm Trees (2019). Exhibition view: How to Build a Lagoon With Just A Bottle of Wine?, Lagos Biennial (26 October–23 November 2019). Courtesy Lagos Biennial.

Under the direction of Folakunle Oshun, the second edition of the Lagos Biennial (26 October–23 November 2019) includes works by over 40 Lagos-based and international artists, architects, and collectives. Curated by architect Tosin Oshinowo, curator and producer Oyindamola Fakeye, and assistant curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago, Antawan I. Byrd, practitioners were invited to respond to Nigeria's former capital (replaced by Abuja in 1991).

The exhibition's title, How to Build a Lagoon With Just A Bottle of Wine?, stems from 'A Song for Lagos' by Nigerian poet Akeem Lasisi, who describes the city as an 'aquatic land'.[1] Lasisi's poem harks back to Lagos' origins as Eko, a coastal village settled by the Yoruba people in the 14th century, before the Portuguese renamed it Lagos in the 18th century and built slave ports across the settlement. British colonialism followed, cementing the city as an important economic hub with longstanding European contact; then came independence in 1960 and a period of growth fuelled by oil and industrialisation. The 1980s and 1990s brought decay, disruption, military dictatorship, and political instability. Today, Lagos is Africa's most populous city, with a population of over 21 million people.

This brief historical account sets the tone for the complex poetics of place that have left indelible marks on the social, political, and cultural fabric of Nigeria's economic, business, and cultural centre. To most people, observes professor Niyi Akingbe, 'the very name Lagos reverberates paradoxical images of population explosion, chaos, nagging traffic jams, filth, disarming wealth and limitless opportunities in contrast to suffocating poverty and shameful beggary.'[2]

The Biennial's curators have responded to this well-trodden view by resisting the fetishisation of Lagosian urbanism and its informal economies by bringing urban-focused, Lagos-based practices into conversation with those asking similar questions from around the world. Art, architecture, environmentalism, and urbanism intersect in newly commissioned and existing artworks by participants including Jess Atieno, Sabelo Mlangeni, Dominique Koch, Tom Bogaert, and Dane Komljen, as well as Lagos-based architecture and urbanism firms HTL African and MOE+ Art Architecture.

The exhibition takes over three floors of Independence House, an abandoned 25-storey office block from the 1960s located on Lagos Island that was once a beacon of modern architecture in the city.[3] One of the most striking works is Rahima Gambo's A Walk Sculpture, Lagos (2019) on the second floor: an installation that portrays the global character of a metropolis like Lagos. The assemblage involves elements interconnected by copper rings, including plants growing out of repurposed Good Mama detergent powder (a popular detergent brand imported from China) and Golden Penny Semovita sachets (the leading brand of Semolina in Nigeria), concrete slabs, a rotting pineapple, and lemons.

Gambo's installation is part of an ongoing series that adopts walking as a critical tool for mapping an embodied experience of the city from its interiors. For this project, she transforms detritus collected on her walks through the city into a constellation that visualises new ways to read—and uncover—its layers.

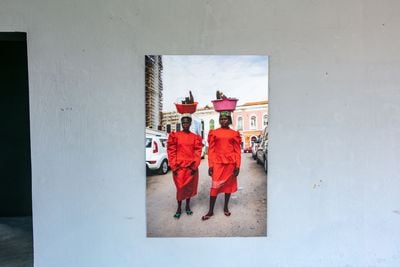

Next to Gambo's installation is Plastic Broken Chairs, Juxtaposed (2019) by collaborative duo Raul Jorge Gourgel and Sandra Paulson: five large-format portraits of female workers (tailors, street hawkers, and food and drink sellers) positioned in various urban sites and places of work wearing red dresses designed by the artists and embroidered with wearer's names, with matching garments assembled as a floating hanging sculpture in the exhibition space. The installation reflects on the labourers that play a central role in Luanda's economy, but who are often rendered invisible and left to endure inadequate living and working conditions.

The active roles of architecture and urbanism in shaping past and present environments, individual and collective behaviours, relationships to living and non-living things, as well as overlooked communities, reverberate throughout this exhibition. Sabelo Mlangeni's photographic essay The Royal House of Allure (2019) provides an insight into queer communal living and the emergence of a new social space in Lagos, while Tom Bogaert's Ant Farm Lagos (2019) deftly renders Lagos Island as a living organism with colourful agar, a vegetarian gelatin substitute combined with sugar, tea tree oil, weeds, soil, black ants, and white wine.

Karl Ohiri draws attention to the way people who live with disabilities try to overcome the many practical challenges of navigating Lagos. The video installation Rolling Footage (2019) was filmed entirely on a GoPro camera attached to a young man's head. The right screen follows him as he pushes through the city using his arms as feet, giving the viewer a unique perspective of the day-to-day struggles and triumphs of navigating the city. The second screen shows the protagonist building a self-styled skateboard as a form of transport in 21 minutes.

Looking out across the horizon to the interplay of functional and dysfunctional architecture that inhabits the Lagos cityscape, this Biennial succeeds in capturing Lagos through the lens of contemporary artists who live and work here while also drawing parallels and connections to the diaspora. Connecting Lagos to London (Peckham is home to the largest overseas Nigerian community in the U.K.) is a work by British-Nigerian siblings Tolu and Ade Coker, who tackle personal histories and inter-generational forms of storytelling with Masqueraded Memoirs (2019). Their multi-part project composed of photographs, film, and large-scale tapestries restage family albums and community archives to portray the exchanges and relations between the diaspora and their country of origin.

This migratory trajectory continues in the work of Adeyemi Michael (another British-Nigerian artist) whose monumental multi-media installation Entitled (2019) reimagines the artist's mother's experience of migrating to the U.K. over three decades ago. The 4-minute film depicts his mother dressed in Ìró and Bùbá (Yoruba dress for women) reflecting on her dual British-Nigerian identities in her mother tongue, while riding through the streets of Peckham on a black stallion. Accompanying the work is a pair of shoes and 32 geles—head-ties worn by Nigerian women—that mimic the country's first skyscraper and the number of years the artist's mother has spent in the U.K. They are placed on plinths in homage to bodies that continue to connect and traverse borders.

The most considered response to the Biennial's thesis, located on the third floor, is a multi-media, floor-based architectonic installation titled A History of A City In A Box (2019) by Ndidi Dike. Mirroring the geometry of an urban cityscape, hundreds of wooden box files from the Nigerian civil service containing archival documents are assembled together with different coloured soils collected from around Lagos and southeast Nigeria, newspaper clippings and historical images of Broad Street and the Independence Building sourced from the private archives of Tam Fiofori, a pioneering photographer and Nigeria's most renowned documentary photojournalist, and H.S. Freeman's post-colonial era postcards. The work responds to the concealment and protection of information as this relates to pre- and post-colonial power systems operating out of public sight by symbolically digging up the ghosts and silences inherent within the archive in order to reveal histories that those in power so diligently try to keep hidden away from both public (and cultural) record.

Ghosts are brought into the present on the ground floor of Independence House, which houses a large-scale mosaic by Yusuf Grillo, an important Nigerian modernist, as well as bas-relief sculptures by Benin-trained sculptor, Felix Idubor. As Byrd points out, these elements echo the building's heyday and its celebration of modern art. Within this frame, it was conflicting to observe, upon exiting the show, an official brochure advertising governmental plans for the future development of Independence House and its environs as a world-class national trade and international business centre, with no indication of when this development will commence or if any part of this masterplan will allocate space for art and culture.

This looming reality speaks to motives that the Lagos Biennial seeks to counter. Reflecting on the future, co-curator Oyindamola Fakeye hopes that the institution will continue 'to bring together architecture, design and urbanism in conversation with contemporary art.' This hope sets an example for future curators, Fakeye explained: an invitation to recognise 'the importance of activating historic sites for shaping present experiences of this versatile city.' —[O]