Made in L.A. 2018 at the Hammer Museum

Charles Long, paradigm lost (2018). Exhibition view: Made in L.A. 2018, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (3 June–2 September 2018). Courtesy Hammer Museum. Photo: Brian Forrest.

For its fourth iteration of Made in L.A.—the Hammer Museum's biennial exhibition exclusively showing works by Los Angeles-based artists—curator Anne Ellegood and assistant curator Erin Christovale assert that there is no theme. Hence, the title: Made in L.A. 2018. The exhibition, which runs from 3 June to 2 September 2018, includes a roster of 33 artists, two of whom work as a collaborative duo, and consists mainly of new works, some of which have been made for the exhibition.

Yet, while themeless, this Los Angeles biennial is in no way directionless, as asserted by the show's curators. Certain focuses include interdisciplinary processes, with many artists exploring new media, and generational dialogues between emerging and mid-career artists—the latter of which have not been exhibited frequently nor widely, despite being 'active in systems of pedagogy' in the city. Contrary to what Made in L.A. 2018's title suggests, this exhibition's perspective is not limited to Los Angeles. Its main aim, according to Ellegood, is to offer 'a response to what's going on in the world right now'. Yet, with a lengthy list of issues plaguing the world today, Made in L.A. 2018 seems to lose itself simply in trying to address it all. That being said, the show succeeds when the focus is on ideas of belonging and marginalised histories (and futures), particularly those that assert their identity as artists living and making work in California and Los Angeles.

Taking over the entire museum, the show begins with La China Charada (2018): Candice Lin's installation referencing the coolie trade in the late 19th century, when forced Chinese labour and indentured servitude was commonly practiced in the Caribbean and California—a result of the need to fill abolition's vacuum of mass, cheap labour for working plantations in British colonies and American projects like the Panama Canal. Made especially for the biennial, the work is presented in a secluded room blanketed in a phosphorescent, hot pink light. The floor is covered in red clay, with the shape of a body pressed into a rectangular clay mound in the centre of the room. The title of the work refers to the 'Charada China', a gambling game with magical associations from various sources—including Chinese, African, Indigenous and European—that was brought to Cuba during the spread of 'coolie' labour. Reflecting on this hybrid product of cultural exchange resulting from a lesser-known and fraught geopolitical history, are indigenous seeds (including poppy, sugar cane, and poisonous plants from the Caribbean) that have been incorporated into the clay mound, which will be watered throughout the exhibition.

Lin created the work after a trip to the Dominican Republic, where she learned about this 'lost history', as assistant curator Erin Christovale puts it, of Chinese coolie labour. Her piece is a dedication to these labourers—many of whom were kidnapped into the trade. Staged like a burial site or memorial, candles and commemorative objects and other artefacts are placed about the space, such as a model ship not unlike those that transported the Chinese indentured servants. Among these is a reprinted 1870 newspaper clipping from Harper's Weekly with a cartoon of a wall, and large text that states: 'THE "CHINESE WALL" AROUND THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'. In the cartoon, a ladder placed by people of Chinese descent, as indicated by their bamboo hats, is thrown off by those on the other side of the wall hailing a flag of 'Know-Nothings'—an American nativist anti-immigration political party. This historical record offers a disturbing reflection of contemporary America today. The wall could stand for the Mexican-American border.

Further inside the museum in another room is Gelare Khoshgozaran's 16mm quasi-documentary film Medina Wasl: Connecting Town (2018), which explores mock villages in the Californian desert, constructed to recreate certain environments—specifically those of Afghan or Iraqi towns—as training environments for the U.S. military. The film is projected across from a wall installation of steel drum closure bungs arranged in evenly spaced rows across the entire wall. The steel drum closures, which look like octagonal steel tops, are used to seal oil containers, which allude to oil as one of the major reasons behind U.S. invasions of Middle Eastern countries.

Khoshgozaran's film renders a landscape native to L.A. foreign and other by studying its transformation into a pseudo-Middle East created on home turf for the purposes of war games. In her online article for art journal X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly, 'Terrorientalist Landscapes', Khoshgozaran compares these mock desert villages to 'the colonial villages on display at the world fairs ... as far back as the mid-19th century'. Still shots of an empty pseudo-Middle East are accompanied by audio interviews with American war veterans that play in the background: 'Nothing but dirt and sand', says one veteran describing his deployment in the Middle East; 'everything smells like burning clay'.

Lin's and Khoshgozaran's works both use localised issues in California to extend the context of L.A. into the larger global landscape. In the case of Lauren Halsey's The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture) (2018), up the stairs from Lin's and Khoshgozaran's pieces and situated front and centre outside the main galleries on this floor, visitors walk into a large atrium honouring Halsey's South Central neighbourhood. The structure is made of drywall applied to plywood with gypsum—a material the ancient Egyptians used in pyramid constructions. Inscribed onto the walls are hieroglyphics and inscriptions communicating cultural and historical legacies of black life in Los Angeles, including UFO-like vehicles (not unlike Sun Ra Afrofuturist symbols), the Air Jordan symbol, and 'My Hood' repeatedly drawn in the form of a graffiti tag. Aside from these, names of victims of police violence, such as Trayvon Martin and Sandra Bland, are also visible.

At once a memorial and a mausoleum of sorts, The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture) is a prototype for a public landmark to be built on Crenshaw Boulevard in Los Angeles, home to many black communities and an African bazaar frequented by the artist in her childhood, which has been experiencing gentrification. The monumental piece literally incorporates the community, since it was built with Halsey's family members and also includes columns with portraits of people Halsey knows. As in Lin's and Khoshgozaran's works, Halsey's monument presents a culturally-rich history. Its placement in this museum, and the knowledge of its eventual construction on Crenshaw Boulevard, situates Halsey's work in an institutional art setting and demands the same sense of belonging that it must fight for amidst the gentrification of its intended home in South Central. Unlike Lin's and Khoshgozaran's works, which intentionally leave the question of the future open, Halsey takes charge of the future, with the installation's future placement on Crenshaw Boulevard to be used as a space for meetings, workshops, and other events.

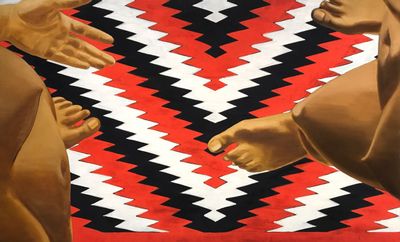

Throughout Made in L.A. 2018, the relationship between the environment, capitalist expansion, and the body emerges as another theme, best demonstrated by one of the older artists in the exhibition. Ninety-seven-year-old Luchita Hurtado is represented by a group of 11 large, oil on canvas paintings made between the 1960s and 70s: self-portraits rendered from above, whereby Hurtado's arms, legs, or breasts are semi-visible against patterned floors. (Hurtado created the paintings in domestic settings, placing props on patterned floors, from fruits to woven baskets, and then painting her body within the frame.)

Charles Long's installation paradigm lost (2018), displays a room full of chopped, phallic trees made from papier-mâché and plaster (see lead image at the top of this report). The work was inspired by the deteriorating landscape at Mount Baldy, where Long resides, about an hour away from Los Angeles. The installation also includes references to Surrealists and other major male artists, like Salvador Dali and Edvard Munch, through the inclusion of frightened faces and cut off cross-sections of the trees that look like melting clocks hanging on what is left of the branches on Long's stumps. These references, specifically the indication of cutting off that which is phallic and associating this with major canonical male artists, offer a critique of patriarchal conditions that dominate historical narratives—something wholly enacted in Made in L.A. 2018, given the roster largely puts at the forefront, in a non-tokenising manner, women artists. Indeed, the exhibition continuously approaches the issues of visibility without ever making it entirely explicit, particularly by showcasing artists that have either been 'emerging' for decades, or those who might not be well known, but have something worthwhile to say.

Los Angeles is many things in this iteration of the biennial. By far, the city becomes a teacher for both non-natives and natives alike about histories that have been left out of the main narrative. Made in L.A. 2018 brings these various histories together in order to think about how new perspectives and solidarities might emerge through a reconnection with the past. —[O]