New York Arts Week: Five Exhibitions Not to Miss

There are few cities in the world like New York for viewing art. If you are in town for the Armory Show, or the ADAA’s Art Show, or the plethora of other art fairs on during New York Arts Week (29 February to 7 March), then you should definitely make sure you see the big shows, such as Laura Poitras at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Marcel Broodthaers at the Museum of Modern Art, Anri Sala at the New Museum, and Peter Fischli and David Weiss at the Guggenheim. But you should also set aside some time during the week to visit shows at smaller non profit spaces throughout the city. Below, is a list of the five we recommend to see.

Jennifer Bartlett: Hospital

The Drawing Center

35 Wooster Street, New York, NY

22 January – 20 March, 2106

One who has ever been faced with a long hospital stay wonders, ‘How does the mind and body endure the boredom?’ Jennifer Barlett’s exhibition is the antidote to that fear. Consisting of ten pastels based on a series of photographs Barlett took during an extended stay at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York in 2012, the paintings show that when a creative mind is stuck in a sterile environment, it begins to pay close attention to exquisite details. For example, the way an automatic glass door can take on a blue, almost crystalline quality, when seen at the end of a long corridor lit by harsh fluorescent lighting. Or, the way light changes the shape of things throughout the day, transforming window panes into infinite planes, objects in the foreground of a window into solid, shadowy masses, and the water on the East River into a streaked mass of polluted colors.

In the past, pastels have acted as a sort of travelogue for Bartlett. Wherever she traveled—Cape Cod, Bermuda, Aspen, Iceland, Mayeaux, Sun Valley, Amagansett, Brooklyn—she captured the place with a pastel afterwards. Born in 1941 in Long Beach, California, Bartlett has since shown her work around the world, and most recently in a retrospective, Jennifer Bartlett: History of the Universe—Works 1970–2011, which was curated by Klaus Ottmann, and traveled to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Parrish Art Museum in the Hamptons, New York. Hers has been a vivid life full of movement, which is why her depiction of being trapped in one place, dictated by the sameness of routines and vistas, is so poignant. She shows that even in a place of confinement, an artist can flourish.

Image: Exhibition view, Jennifer Bartlett: Hospital, 2016. Courtesy of The Drawing Center, New York. Photo by Martin Parsekian.

Cameron Rowland: 91020000

Artists Space

38 Greene Street, New York, NY

17 January – 13 March, 2016

In his exhibition 91020000, the young artist Cameron Rowland deals with a different kind of confinement: imprisonment within American’s penal system. Taking its title from the customer number he acquired from Corcraft, the New York state agency that sells products made by inmates to schools, universities, courts and police departments and certain non-profit groups, the exhibition is part sculpture, part installation, and part political treatise aimed to bring to light the fact that in the United States, although we no longer have legal slavery, there are arguably still systems of enslavement that operate in full view.Without reading the extensive captions on the wall, and Rowland’s accompanying brochure—which suggests a path from legal slavery in the ante-Bellum south to what arguably could be viewed as another form of slavery, incarceration, in which inmates work at rates below the minimum wage—the actual works in the exhibition would only conjure up vague associations. Four wood benches are grouped closely together near a line of windows, conjuring up pews in a church: in actuality, the benches were made by inmates, and are used in courtrooms, facts that are denoted in extensive captions. Cast aluminum rings are arranged around a wooden pallet as if they fell off during an abandoned construction project—again, made by inmates, the rings are used by inmates installing manhole covers in roads. Two firefighting suits, one orange and one hang along a wall, and the accompanying caption says that they were made in a California prison, and that the orange suits are for ‘inmate firefighters’, while the yellow suits are for ‘non-inmate firefighters’.

The show, which fills the entire light-filled loft of Artist’s Spaces’ Greene Street location, is sparse—but in its sparseness, more powerful. We do not see the laborers who created the actual objects, just as they remain invisible behind the walls of prisons. Their absence, in the exhibition, is a powerful presence—and a reminder of the fact that in the United States, there is a prison population of 2,220,300, roughly 60 per cent of which, is African American.

Image: Cameron Rowland, Attica Series Desk, 2016. Steel, powder coating, laminated particleboard, distributed by Corcraft. 60 × 71.5 × 28.75 inches. Rental at cost. The Attica Series Desk is manufactured by prisoners in Attica Correctional Facility. Prisoners seized control of the D-Yard in Attica from September 9th to 13th 1971. Following the inmates’ immediate demands for amnesty, the first in their list of practical proposals was to extend the enforcement of “the New York State minimum wage law to prison industries.” Inmates working in New York State prisons are currently paid $0.10 to $1.14 an hour. Inmates in Attica produce furniture for government offices throughout the state. This component of government administration depends on inmate labor. Courtesy of the artist and ESSEX STREET, New York. Photo: Adam Reich

Martin Wong: Human Instamatic

The Bronx Museum of the Arts

1040 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NY

4 November — 13 March, 2016

There’s an argument to be made that one should go see Martin Wong’s retrospective at the Bronx Museum of Art if only to ‘discover’ one of the five boroughs of New York City yet to be colonised by the art world. But Martin Wong alone is reason enough to make the trip to the city’s northernmost edges. Born in 1946 to a Chinese American mother, and a Chinese American father who also had Mexican ancestry, Wong referred to himself as Chino-Latino. After studying art at Humboldt State University, Wong came to New York in 1978, where he lived first in a crumbling hotel near the South Street seaport, and then in a neighborhood on the Lower East Side known as Loisaida for its black and Latino residents. In New York, he began to paint in earnest, capturing the streetscapes throbbing with life. Life in New York is the subject of his retrospective at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, which consists of 90 paintings, as well as archival works, made over the course of Wong’s career, until he died from AIDS related complications in 1999.The show is a document of not only New York, but also homosexual life and the AIDS crisis. My Secret World, 1978-1981 (1984) shows the interior of a tiny room from outside the brick wall that contains it: inside is a neatly made bed, a mug sitting on top of a stack of suitcases, a pile of books on top of a dresser. It will be achingly familiar to anyone who has ever lived in a tiny space in New York while they tried to ‘make’ it, or to those familiar with Van Gogh’s interiors, which the painting resembles. Big Heat (1988) shows the still somewhat shocking image of two male firefighters kissing while a tenement building burns behind them. Attorney Street (Handball Court With Autobiographical Poem by Piñero) (1982-84) is both a snapshot of a graffiti mural on a handball court long since torn down, as well as a homage to Wong’s lover, the poet Miguel Piñero, Like much of Wong’s work, it is ripe with a wealth of details: the graffiti itself, the chain link fence, the walls of buildings behind it, but also, three rows of hands using American sign language symbols to spell out hip hop lyrics.

The show is aptly titled ‘Human Instamatic’ because Wong is the equivalent of today’s Instagram street photographer: an artist who captured, in minutiae, the world around him in vivid detail, and shared it through his imagery. The show has been extended through New York Arts Week.

Image: Martin Wong, In the Money, 1986. Acrylic on canvas, 48 inch diameter. Courtesy of the Estate and P.P.O.W, New York.

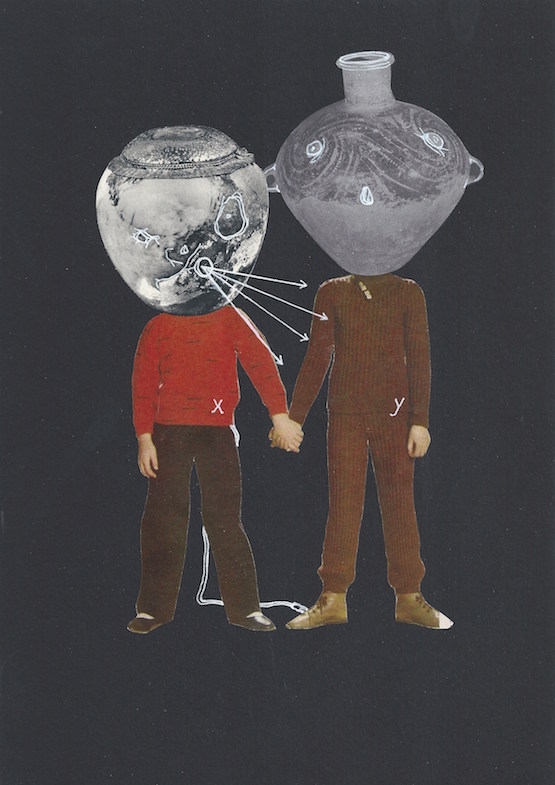

Eva Kot’átková: ERROR

ISCP (International Studio & Curatorial Program)

1040 Metropolitan Ave. Brooklyn, NY

2 February 2016 - 8 April 2016

Located on the industrial edges of Williamsburg, where the up-and-coming neighborhood meets even more up-and-coming Bushwick, the ISCP is a great satellite point for touring Brooklyn galleries such as Microscope, Regina Rex, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, the Knockdown Center, Pierogi and Extra Fancy. But it’s also a destination point in itself, showing artists who are just on the verge of hitting superstardom.One such artist is Eva Kot’átková, a Czech-born artist who received international acclaim for her installation at the Encyclopedic Palace curated by Massimiliano Gioni at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. She was already well known in her country of origin for being the youngest person ever—she was born in 1982 —to receive the prestigious Jindřich Chalupecký Award for artists from the Czech Republic. Since the Venice Biennale, her work has also appeared in institutions around the world, including at the New Museum Triennial in 2015.

Her current exhibition, ERROR, at the ISCP, is slight, but deeply thought provoking. Consisting of a wall of collages, two installations of sculptural assemblages, a marionette puppet, a suit for recording people through their own windows, and an hour-long video.The show examines those who do not fit into the strictures of society—and most specifically, the mentally ill. In particular, Kot’átková is interested in the hallucinations and imaginings of patients at the Psychiatric Hospital Bohnice in Prague, which opened in 1908, and still operates today. Aleš’s devices to measure the world (2016) is a wall installation of bizarre medical devices invented by a surgeon who became a patient at Bohnice in the 1910s. Anna (from Theater of Speaking Objects) (2016) is a marionette puppet based on a drawing by another patient, who depicted herself wrapped in a Persian rug so that no one could see her inside. The Judicial Trial of Jakob Mohr is a video based on a 1919 drawing by Mohr, yet another patient, who believed himself to be controlled by an empty box that emitted electromagnetic rays—in the video, he is given the chance to prove to a jury of patients and doctors that his delusions as truthful.

Overall, the show raises powerful questions about the connections between mental illness and creativity. Are the mentally ill, by virtue of not fitting in to society, tapped in to some higher consciousness that allows them to express creative genius? Or is the act of creation needed in order to free oneself from the burden of one’s own mind? All questions interesting not only to the mentally ill, but also, anyone involved in creative endeavors.

Image: Eva Kot’átková, Error, 2015-2016. Collage on paper. 11 3⁄4 x 8 1⁄4 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Meyer Riegger, Berlin/Karlsruhe and hunt kastner, Prague.

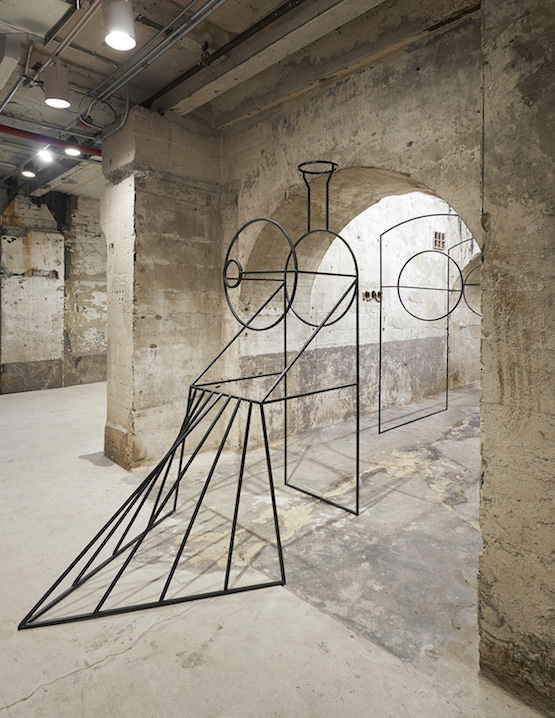

Rochelle Goldberg: The Plastic Thirty

SculptureCenter

44-19 Purves St, Long Island City, NY

24 January – 4 April, 2016

In a bold move the SculptureCenter has announced that all of its 2016 solo shows will feature projects exclusively by female artists. It won’t make up for years of exclusion from the art world, but it’s certainly a boon for artists who benefit from the publicity surrounding such a curatorial statement.The female artist showing at the Long Island-city based stalwart during New York Arts Week is Rochelle Goldberg, who was born in 1984 in Vancouver, and currently lives in New York. Rochelle Goldberg: The Plastic Thirty is her first solo institutional exhibition. And it is deserved. Her incredible creations, which are made from living and synthetic materials such as chia seeds, crude oil, ceramic and steel, look less like static artworks than they do invasions by alien species that have come to live in the various hidden coves and crumbling spaces of SculptureCenter’s industrial galleries. For Every Living Carcass I (2016) is a molten skeleton of a fantastical fish that could easily serve as a set prop in some forgotten land in Game of Thrones. Original Spill (2016) is a steel and glass wreck laid out between the walls of an entirely darkened corridor, and lit from below as if it came from some primordial star system. Try Again I, II, III, IV, V (2016) betrays a wry humor, showing a magic eight ball that displays messages such as ‘Still choking try again’, or ‘You need a body of water’.

The show evokes both the beginning of the world and the end of it. It is an apocalyptic dream that’s surprisingly beautiful, and one arguably best seen at the end of the Arts Week, when you’re exhausted from the sheer magnitude of works you’ve seen at the various fairs, galleries, and institutions. —[O]

Image: Rochelle Goldberg, Iron Oracle, 2016. Exhibition view, Rochelle Goldberg: The Plastic Thirsty, SculptureCenter, 2016. Steel, chia laced with steel, earth. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kyle Knodell.