No More Triumphs: A Report on Asia Contemporary Art Week (ACAW) 2015

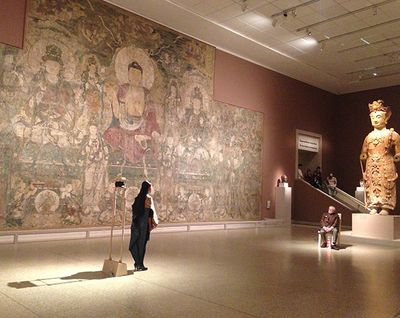

Lee Mingwei, Sonic Blossom, 2015. Performance view from The Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art, New York.

'I don't have a concept of place anymore,' was the response given by Ming Wong when asked about representing specific geographies during a panel as part of New York's 10th Asia Contemporary Art Week (ACAW), 2015. Presented by the Asia Contemporary Art Consortium (ACAC), it brings together 150 artists, curators, and writers in collaboration with around 40 institutions, both Asia and New York-based, from the 28th October to the 8th November. The event offers both a focused platform for critical discourse, and a related programme of exhibitions and performances throughout the city over ten days.

The signature FIELD MEETING event took place over the first weekend, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the downtown Hunter College Galleries. The concept is spearheaded by ACAW Director and Curator Leeza Ahmady, and presents itself as an opportunity for presenters to talk through action, both individually and collectively, under the theme Thinking Performance, with a public audience in attendance.

The keynote was presented by Holland Cotter, The New York Times art critic since 1998 and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 2009. 'I remember a time when a week like this was unimaginable,' he began; focusing on New York City itself as a backdrop for the institutional representation of Asian art in America since the late 1980s, Cotter noted the Queens Museum and individuals, such as Alice Yang, who championed this new content out of context in a largely hostile environment. In an extraordinarily humble and personal exposition of why Asian art must and does matter, he called upon the system of art criticism itself to stop celebrating one artist, one region, or one style in triumph, eclipsing others as though the story were over. He cited Ai Weiwei as 'the stereotype of a Chinese dissident,' and El Anatsui as the stereotype of upcycling African artist. 'Let's have no more triumphs. Triumphs are over. No more look at this but not that. It's time for Asian art to sit at the table with everyone else.'

Concerns over history, representation, power, access, language, and 'placeness' dominated the two-day session. Defne Ayas, co-founder of Arthub Asia and now the director and curator of the Witte de With Centre for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam, spoke of working to eliminate boundaries, for example, 'scrapping the exhibition structure' in favour of artist participation as was the approach to the 6th Moscow Biennale, the intention being to bring audiences closer to the mind of the artist. Slovenian artist Ištvan Išt Huzjan described his travels through Korea and the resulting 'studio as journey,' urging us all to be vigilant moving through cultures and histories, but mindful of personal trajectory. 'We must keep asking ourselves, where are our traces leading us?'

Audience questions demonstrated a desire for clarification of certain terms used across numerous presentations, namely 'the third space' and ethical concerns in practice. Leeza Ahmady, defined 'the third space' as 'incorporating images and history without shame or guilt.' One audience member added the question, is it 'where contemporary power structures are dismantled?' Holland Cotter felt 'the third space' was a new language formed by traveling from Asia to the West and back again. 'On a panel at MoMA they brought a curator from Lagos who managed a museum with a collection but no home. The sense was that he should be learning from MoMA how to survive—but of course, MoMA should be going to Lagos. And that will happen, when MoMA decides it can happen.'

Chinese artist Tang Dixin, known for his socially critical performances, described his work as 'the process of resistance and empathy.' Much discussion revolved around the porous nature of performance and its ability to transcend time and locale, replacing language and image with body and gesture. Nadim Abbas, in discussion with LEAP deputy editor Robin Peckham, spoke of transitioning from bodies and language to objects and back again: 'What's an inanimate gesture? What's the gesture of an object?' Ming Wong presented his sets for science fiction operas as future voyages into the fantastic, borrowing from a diverse range of theatrical canons led by characters upon whom 'our desires can be projected.' Iftikhar Dadi, Chair of the Department of Art at Cornell University, praised the quality of performance to capture 'presentness and temporality' unlike any other medium, and that this was particularly significant in the framework of Asian art which falls victim to certain historical tropes.

Cultural dominance came up repeatedly, largely in terms of market power, but also in institutional models. Defne Ayas warned of 'copy and paste' institutional models seen throughout Asia, while also identifying this as it's own kind of cultural practice. Holland Cotter spoke of 'the third language,' which is something both culturally specific yet globally relevant, citing his own short sightedness in seeing early contemporary Asian art as 'derivative.' The Chelsea Galleries Night illustrated the market imbalance; a small cluster of Asian galleries drew modest crowds, while New York mainstay Pace Gallery was heaving in celebration of a new Zhang Huan exhibition (Pace was not part of the ACAW programme). It begs the question; does being quantifiably Asian prove to be a limitation? Independent curator, writer and researcher Natasha Ginwala explained that Asia's strength would be mobility and flexibility in a highly networked community, seizing communication channels as and when needed.

Monday 2nd November featured a collaborative event with New York's Performa 15, and was rooted in discussion around the 'performance lecture'—a format that has been gaining traction throughout Asia, in which artists can 'perform' the words and language of their work in the style of a talk or lecture. There was much debate over what this meant in practice, and whether it was an effective medium. One audience member proposed that what was so attractive about the lecture-performance was precisely 'it's promiscuity, which it shares with the art world,' adding that 'it's an expository format, but it is also a conceit. It's a desire for artists to reclaim the words and interpretations attached to their work.' The panel seemed visibly awkward when pressed to speak about representation of place, about the inability of non-native languages (specifically English) in communicating ideas which are culturally specific.

Many conversations cycled back to the concept of Asia, and what it means to either be from there or connected to a practice which is perhaps too broadly clustered in such a vast and diverse region. In his closing remarks on the FIELD MEETING, Iftikhar Dadi remarked that the term 'Asian' is problematic now because Asia contains the majority of the world's population. Perhaps that category is not useful anymore? Leeza Ahmady, explained that 'Asian contemporary artists are traversing a geographic area to somewhere which is more conceptual and philosophical ... I have beside me a curator [Natasha Ginwala] with an Asian background curating European Biennials, which is really important.'

Numerous audience members wept following performances of Lee Mingwei's Sonic Blossom at the Met, in which opera singers approach individual visitors to listen to a brief Schubert lieder in the Asian galleries. It seemed a good indication of ACAW's goals in practice: culturally specific art forms converging rather than triumphing over one another, managing to be both universal and intimate at the same time.—[O]