Ocula Report: Formosa 101, Taipei

Formosa 101 Art Fair’s inaugural show in Taipei this May had a low turnout of visitors and a number of mishaps, and yet it displayed some stunning presentations. The fair was organised around solo shows by invited galleries from Taiwan, China, the Philippines, Korea, Japan, with a Germanic side-serving due to a special event undertaken in partnership with ART.FAIR from Cologne.

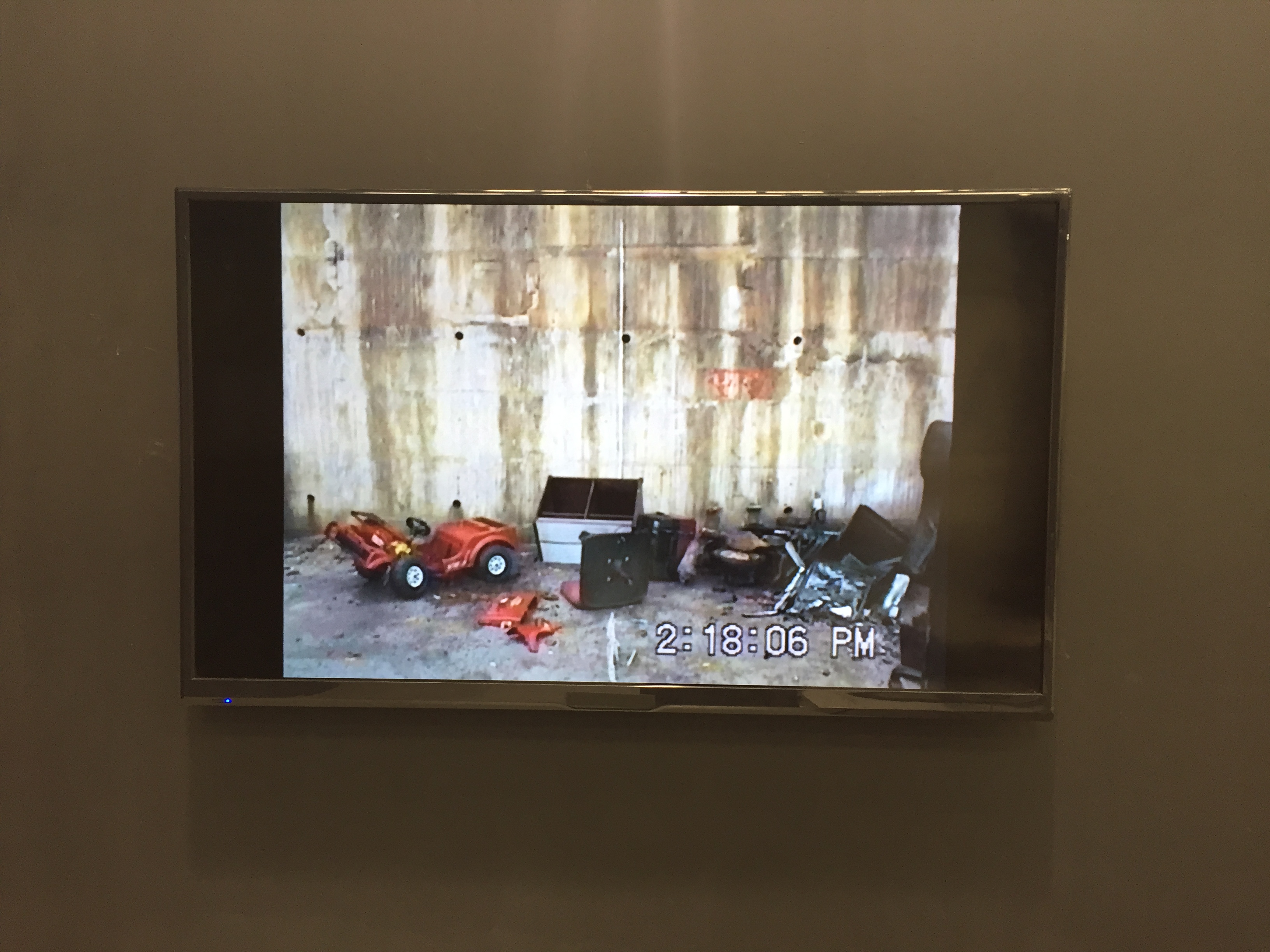

A special video section, curated by Chi-Wen Gallery, gathered some notable pieces together. For example, Project Fulfill Art Space presented Chim↑Pom’s Black of Death (2007) which depicts crows following the artists in a grim chase, and enticed by a stuffed crow the collective had made. The same gallery introduced Zhang Xu Zhan’s, Animated Journal Series 1-18 (2012-14), a compilation of creative musings in the form of moving doodles of illogical narratives: a story book of sorts. Chi-Wen Gallery, itself, showed The Welcome Rain Falling From The Sky (1997) by Tsui Kuang-Yu. Tsui is an established Taiwanese, artist whose videos often feature performances about the human condition. In the work a protagonist (played by the artist) is filmed jumping from left to right and back again to avoid falling objects such as flower pots, furniture and TV sets—a visual metaphor perhaps for life’s predicaments and our ability to dodge them.

Taipei-based Star Gallery also had a strong (if not busy) presentation by established Taiwanese artist, Dean-E Mei. Mei has been working conceptually for the last 40 years, (his retrospective at Taipei Fine Arts Museum in 2014 spanned 1976-2014), and he is known for using found objects that relate to questions of identity and politics. He was born in Taipei in 1954 and spent ten years in New York from 1983 to 1992, and describes his work as being about the semantics of identity, beyond national representations or binary analysis. On display, were some of his most effectively humorous sculptures and paintings, such as The Great Jump (2014), a large map of China with a golden knife thrown in its midst (much like one would imagine a knife thrower would indulge a target), hinting at China’s 1958-61 economic campaign titled the Great Leap Forward. Another sharp China-themed piece on show was Razor (2012), a stainless steel sculpture of an oblique large razor blade. Instead of the traditional design for the razor blade’s middle slot, one can discern the profiles of Mao Zedong and Sun Yat-sen facing each other. A visual quip referring to some uneasy history between the two countries, the conflict between its powerful leaders and the dangers that are attached to their unavoidable relationship. Mei’s playful but dark installations reflect the complexity of Taiwanese culture. Using common objects, simple colours, and ready mades to draw collective social memory snippets, the artist proposes a revisiting of the nation’s recent history underlying its multiple spheres of influences (many of his works also embark on questioning art history’s western-centric references) and ultimately leaving the viewer to confront their own stance.

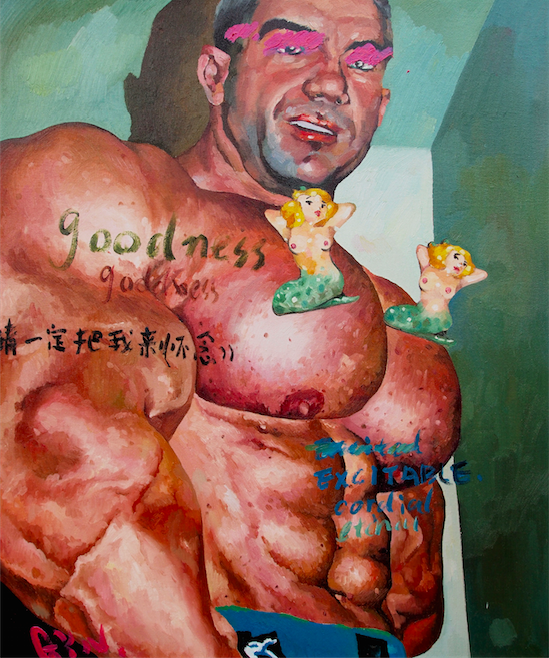

Also abundant with irony, but arguably more concerned with exploring gender-themed issues, were the works of Shenyang-born artist Geng Yini (born 1982). The artist showed oil on canvas paintings which feature pumped-up wrestlers, apes, and body-builders amidst an excessively colourful (red and blue) booth that included boxer gloves and punching balls on stands. Presented by BANK from Shanghai, the artist titled her solo presentation “Heat Wave” and this was accompanied by a sultry poem presented as text across a wall. The works claim to explore the extremes in human nature, with paintings such as Hot Spot (Miss Me When I’m Gone) (2015), depicting in pinkish undertones a tanned body-builder’s chest with a lot of flesh to spare. Another painting, Stage Photo (2016), showed two large (seemingly grinning) apes posing hand in hand in front of a rainbow background. The booth oozed offbeat humour, like a stand up comedy on steroids. Unsure of what to make of its outlandish aesthetics, and yet curious by its anomalistic existence, it attracted and repelled visitors at the same time. In any case, the presentation was absurdly noticeable, and a great pun to the cliché that (Asian) female artists only paint cute and romantic subjects—here was one who groomed a macho-extremism style that she cajoled with virtual boxing gloves.

Tong Gallery showed a series of paintings by Liu Xia (b.1981) that formally explored the signification of the 'eye'. The Beijing-based artist deconstructs his subject—often their faces—to such extent that they seem to be reduced to a few holes or dots. Often in white, his protagonists are either pandas or rabbits, or they are humanoids wearing a wedding dress, Ku Klux Klan’s white robes, nurses uniforms, or other white garments. Exceptionally, in one work, Portrait of a soldier (2016), a dark-skinned man appears; it is apparently a reference to traditional Western representations of black people in paintings. By exaggerating the simplification of the facial features, the artist renders an aesthetic that denies his subjects the ability to connect emotionally (an anti 'window of the soul' of sorts if you like), and yet, the result is haunting. Rabbit (2014) presents a white contour of the archetypical representation of a bunny, but yet what is presented is the depiction of a rabbit mask: all the orifices are see-through holes. His paintings all carry a dark but oddly funny mood. In Three Smoking Terrorists (2014) you see three men in throbes lighting up a cigarette while wearing a large amount of inflammable explosives on their belts—obviously they didn’t think it through. —[O]