'Pattern Recognition': The Young Artist of the Year Award 2016

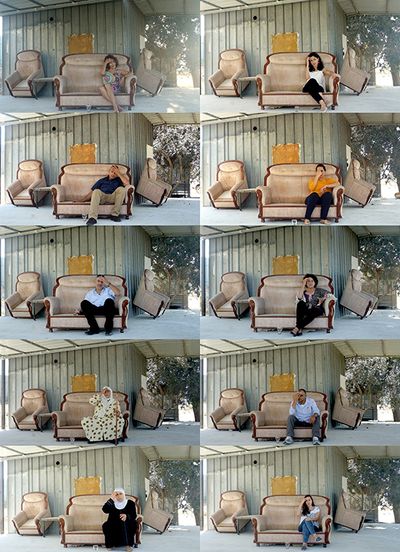

Majd Masri, Haphazard Synchronizations (2016). Installation view: Pattern Recognition, The Mosaic Rooms, London (20 January—18 March 2017). Courtesy The Mosaic Rooms. Photo: Andy Stagg.

Established in 2000 by the A.M. Qattan Foundation, the Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA), also named The Hassan Hourani Award in honour of the late Palestinian artist, celebrates the creative achievements of Palestinian visual artists between the ages of 22 and 30. Curated by Nat Muller, the 2016 award exhibition, Pattern Recognition, was exhibited in Ramallah in October 2016 as part of the third edition of Qalandiya International, a collaborative contemporary art event launched in 2012 and staged biennially in towns and cities across Palestine. (In 2016, the event, which explored issues surrounding the Palestinian right of return as invoked in the title, This Sea is Mine, expanded outwards into other cities for the first time, from Amman to London.) Months later, Pattern Recognition has travelled to London, where five of the nine artists shortlisted for the award, including Inas Halabi, Majd Masri, Noor Abed, Ruba Salameh and Somar Sallam, are currently on view at The Mosaic Rooms, an A.M. Qattan Foundation project (20 January—18 March 2017).

Rather than rely on traditional iconographic content generally synonymous with visual representations of Palestine, such as keys, oranges, and olive groves, YAYA's shortlisted artists were encouraged by the award's curator to consider the politics of form, repetition, pattern and rhythm as emancipatory tools enabling a critical rethinking of such concepts as time, place, memory and authenticity. In so doing, they succeed in experimenting with idiosyncratic alternatives to a more familiar aesthetics of nostalgia.

Appropriately enough, the exhibition opens in the first gallery of The Mosaic Rooms with Inas Halabi's Mnemosyne (2016), a single-channel video for which the artist was awarded first prize. Named after the Titan goddess of memory and remembrance, Mnemosyne is a family history project based on the subject of a scar, or more specifically, an almost indiscernible blemish on the forehead of the artist's late grandfather. The scar becomes the topic of conversation in interviews that the artist conducts with her mother, grandmother, brother, sister, uncles, aunts and cousins, each filmed individually while sitting on a cream coloured sofa positioned on the periphery of I'billin, her mother's village, which is near the barracks where her grandfather was stationed. The result of an injury inflicted by an Israeli soldier in the late 1940s, it becomes apparent as each family member narrates their own version of events, that the scar saga coincides with the tumult of the Nakba—the exodus of more than 750,000 Palestinians who either fled or were expelled from their homeland—and the foundation of the state of Israel.

A reflective as well as a reflexive endeavour, Mnemosyne reveals the ways in which recollection becomes an act of transformation, exploring the relations between collective history, the creation of myth and memory's peculiar caprice. Having finished speaking, each family member drinks from a glass of water, which, as Muller muses, might be seen as an allusion to Lethe, the Greek goddess of oblivion and the name given to the river of forgetfulness flowing through the mythological underworld. As Muller notes, 'the suggestion is that if they told the story again it would be a different story.'

On view in the second gallery room is Somar Sallam's second-prize-winning video work, Disillusioned Construction (2016), in which a crocheted blanket covering a woman's naked body is pulled disconcertingly undone in an arbitrary and endless cycle of construction and deconstruction. Born to Palestinian parents who were living in Yarmouk Refugee Camp in Damascus, Syria as a result of the Nakba, Sallam and her family were forced to flee Syria for a new life in Algeria four years ago. As such, Disillusioned Construction is an affecting and affective visual conceptualisation of Sallam's first-hand experience of the unravelling felt when the war in Syria meant that the Yarmouk refugee camp was no longer a safe place to call home, and her family were once again uprooted, thus highlighting, in the artist's own words, 'the experience of thousands of Palestinian-Syrian refugees—displaced for the second time'.

Also on display in this gallery is Haphazard Synchronisations (2016), a series of six paintings by Jerusalem-born artist Majd Masri, which use a photograph of a Palestinian female fighter dressed in military fatigues holding a flower between her teeth (taken in the 1970s at a Lebananese refugee camp), as the basis for an exploration of Palestinian political and art history. An aesthetic investigation into how artistic practices have been affected by events which have taken place since the Nakba, Haphazard Synchronisations sees the original image strikingly transformed into art historical styles related to Palestine. Masri employs the visual languages of Greek icon painters, prominent Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour, political cartoonist Naji al Ali, and the bold graphics of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine in the creation of each iteration.

Noor Abed's video and mixed-media installation, The Air Was Too Thin to Return the Gaze (2016), shares the partitioned lower-ground floor gallery with Ruba Salameh's Ym/Yamm/[open sea] (2016). Essentially a speculative sci-fi mystery, the subject of the work is an unidentified creature rumoured to have been spotted flying low over the village of Bir-Nabala, northwest of Jerusalem. Taking an archaeological and in many ways forensic approach, Abed collected, and subsequently interrogated, evidence of this (fictional) local sighting; including a technological device with an internal digital memory. The multi-part installation includes photographs of a gathering commemorating the event, an image of the sky (and UFO) above Bir-Nabala taken by a witness on his phone and a silent video in which the artist examines objects found on site. The project shares some of the research she undertook during her residency at the Whitney Museum's Conservation Laboratory in New York last year.

By contrast, Salameh's video piece يم /Ym/Yamm/(open sea) appears at first glance to be an ode to the ordinary in its recurrent documentation of goings on at a bus stop on Salah Al-Din Street in East Jerusalem. Wonderfully ruminative, the artist succeeds in capturing mundanity at its most mesmeric, offering a glimpse of life's curious ebbs and flows. Repetition lies at the heart not only of Salameh's video poem but also of the lives of those she depicts: both passengers and passers-by. And yet, all is not as it seems. Adjacent to the bus stop is a billboard that features a torn and faded image of the sea of Gaza, which is animated by the seamless insertion of filmed footage shot by the artist from the beach at Tantoura—a Palestinian village demolished in 1948. In so doing, يم /Ym/Yamm/(open sea) highlights the fragmented nature of Palestine's geography, presenting a hypnotic vision of an unattainable reality. No longer able to travel freely between Palestine's territories, Salameh—like the people she films at the bus stop—can only wait; doomed, it seems, to inhabit the eternal interim between an endless present characterised by a kind of post-Oslo Accords malaise, and a long hoped for future in which Palestine is an independent state.

The final piece chosen for this exhibition, Homeland is ... (2016), was meant to be performed on 24 February by its author, Asma Ghanem, but the performance did not take place. The work would have consisted of an experimental live sound and music performance for which Ghanem was awarded third prize. Sharing Ruba Salameh's disillusionment with the stagnation of the Oslo Accords process, Ghanem was to render audible the insufferable opposition between sounds of inertia (relating to the stalled process of nation building) and those of occupation (military din). The artist's absence from the exhibition reflected another fact: that the exhibition's Ramallah edition was much larger and more diverse, with three additional artists (Aya Kirresh, Abdallah Awwad and Majdal Nateel) working in large-scale sculpture and sculptural installation work.

It is difficult to write about Palestine without using words like dispossession, displacement, demolition, drones and discrimination. Yet others—strength, resilience, and optimism—seem, in the context of YAYA 2016, much more appropriate. The A.M Qattan Foundation's Culture and Arts Programme Director, Mahmoud Abu Hashhash asserts: 'We have a strong belief that vibrant, inspiring and ongoing cultural work will open new windows and doors through which to look towards the future.' Indeed, the very fact that so many young artists are making work in such challenging circumstances must surely constitute a message of hope in and of itself. Whilst rooted in each artist's individual experience of Palestine, a place where geographies, histories and identities are fragmented, the six works on display reveal preoccupations of universal significance. The relationship between politics and aesthetics, and issues surrounding identity and forced migration are themes that resonate with us all in today's polarised, post-truth, Trumpian world. —[O]