Processing disagreement: 20 Years of Para Site and the 2016 International Conference

Disagreements can be at the heart of development. Yet, despite the oversaturation of critical platforms for debate in contemporary art, instigating a disagreement appears to be a sort of pedagogical taboo. How do cultural workers activate tensions in order to ask difficult questions and speak about contested histories? Is there something more institutions should be doing, not only to encourage criticality, but also to educate visitors of the possibility of disagreeing?

Over the last five years, we have seen a rise in the volume of critical symposia, conferences, and educational programs emerging at an international level. Increasingly such events are linked to the number of art biennales and art fairs emerging across the world, and each has their own discussion format. Art fairs now use ‘conversation’ platforms to add critical legitimacy to their activities, as a way of drawing in—and arguably taking ownership of—the larger art ecology. Even major new museums such as Hong Kong’s own M+ have advocated that learning and interpretation are key to the development of the institution.

In 2012 Boris Groy’s argued that: ‘While contemporary art is often criticised for being too elitist, not social enough, actually the contrary is the case: art and artists are super-social.’ What he means by this is that due to the changing conditions of art, artists and cultural workers must increasingly ‘perform’ their roles around the clock, across a number of platforms, both online and off. Not only this, but more and more, they are occupying and performing multiple roles, i.e. today it is common to meet an artist who also writes criticism and curates. No doubt the multiple roles they occupy sometimes make diplomacy within the field difficult, as they frequently meet ethical crossroads and conflicts of interest. Perhaps it is due to the multiple roles they occupy, that they are less and less inclined to disagree, take a critical position, or risk a relationship?

Para Site, a non-profit art institution founded in 1996 in Hong Kong, was formed very much in disagreement with the current art scene at the time. Like many artist run initiatives it wasn’t fearful of disagreement, actively embracing it and being very much formed as an alternative, a counter-culture to the dominant voice. Since its formation it has undergone a successful transformation whilst still retaining those original politics. It has evolved from its beginnings as a stoical artist run initiative, one of the first in Asia, to an internationally competitive independent art space. Today it aims to foster a critical understanding of local and international contemporary art, and it is this ongoing commitment to criticality that distinguishes it from its peers.

The 2016 edition of Para Site’s International Conference—a three-day gathering of cultural practitioners from around the world (21 - 23 June)—was one such opportunity for criticality. It was a platform to reflect on the historical context of the art community in Hong Kong, and it also offered the chance to analyse where contemporary art intersects with the social, economic and (crucially) the political, and to see what disagreements might emerge in the process. But furthermore it was a testing ground: an opportunity to analyse how cultural workers disagree within public forums, and what provisions the institution might make for this to be possible.

The conference was structured to explore themes where invited participants focussed daily on particular areas for thought and debate. The first day was themed: The 1990s: Identity in the times of the handover and the age of the Biennial; the second: The 2000s: The rise of China and the global art world; and the third: The 2010s: Booms and crises in the age of the art fair. Each day concluded with a panel discussion between the speakers, allowing for a reflective moment to address questions relating to that day’s theme, providing further opportunity to engage with and, perhaps confront, each panellist’s position.

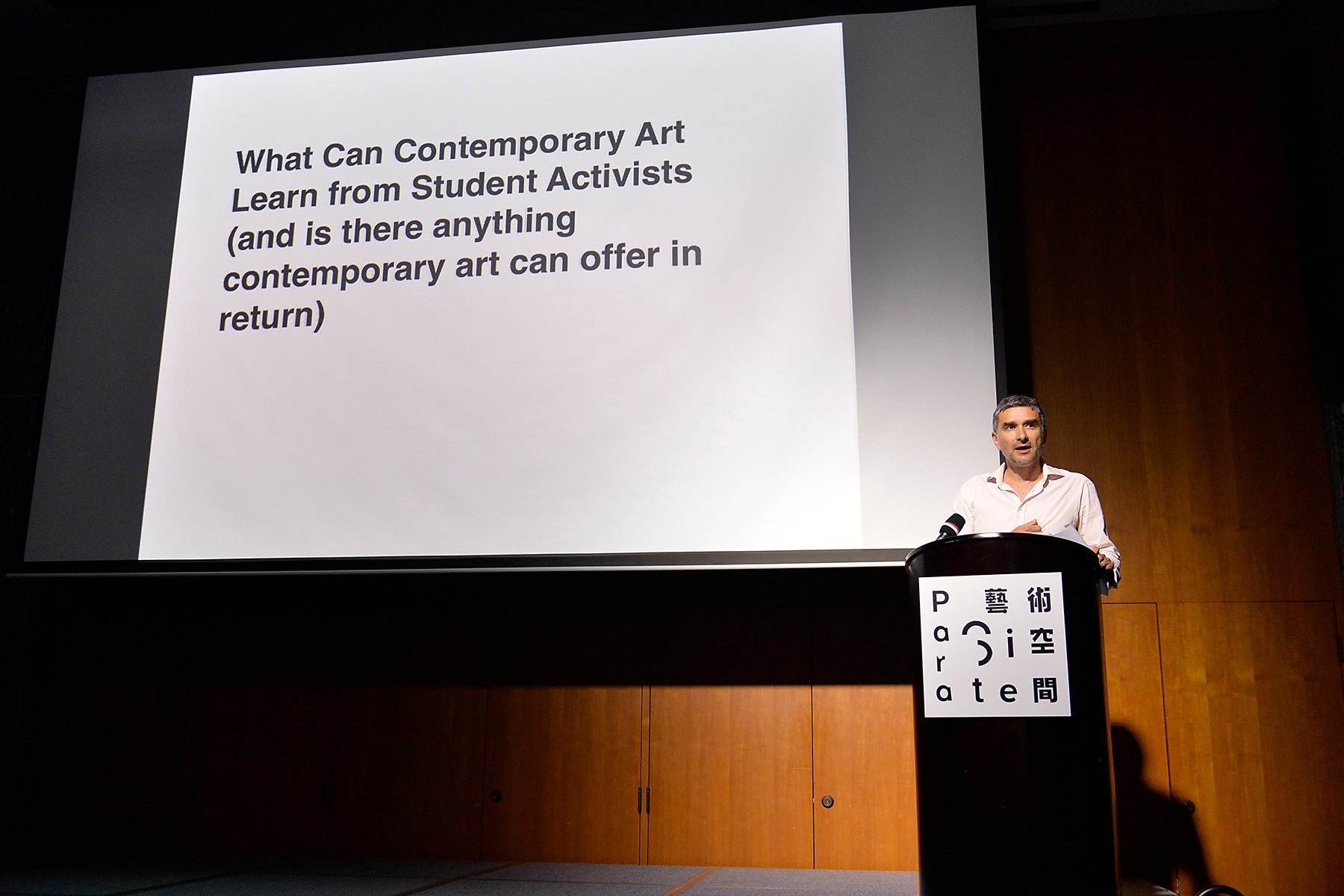

Highlights from the conference included Taipei based curator Amy Cheng’s presentation on day one, where she spoke about the role of disagreement as being critical to the history of Taipei’s art scene. Her presentation referred to the intellectual climate following the 1987 lifting of martial law in Taiwan1 and the sound and performance based counter-culture that emerged in 1992 – 1995 with the Broken Life Festival2. She argued that this, in addition to challenging the local power structures in Taiwan, was also actively critiquing the country’s seemingly blind adoption of Western culture and values. During day two, Roger M. Buergel then went on to propose controversial provocations, stating that 'the West does not exist' and that 'globalisation never happened'. Focusing on contested statements about power relations, Buergel’s talk appeared to resonate in some way with everyone at the conference. On day three Lucas Ospina used humour as a tool to comment on the contemporary art scene’s recent boom in Bogotá. He raised questions about the extent to which publications in the West are still acting as the validators of ‘new’ art ecologies, and to draw attention to these power structures he spoke about a recent article he published ironically titled: ‘Columbia is a normal country’. Later, Arnhem based curator Tirdad Zolghadr took us through a critical overview of the relationships between contemporary art and student activists, proposing that perhaps we now are in a time when we shouldn’t automatically assume contemporary art to be a vehicle for activism.

At the conclusion of the third day, there was not only the facilitated conversation, but also a final plenary discussion, offering the chance for last bursts of energy from Para Site’s public, and opportunities for the audience to weigh in on the overall themes and make connections from key words that emerged during the three days. In terms of event accessibility, the conference itself was free of charge, and live streaming was available throughout the event. In addition to this, each presentation was recorded to add to the ongoing conference archive that the institution is building.

For contemporary art conferences to become meaningful amongst the competing noise, they require not only the representation of multiple voices, but also the fostering of a climate in which the audience are encouraged to engage in healthy debate. What Para Site proved through this conference is that it has the dexterity to generate participation as a marker of critical practice in the field. In a time where asking questions is not always easy to do, particularly in an environment where art professionals occupy multiple roles, one can only hope that other institutions will take up this issue too. —[O]