Shanghai Biennale Mobilises Trans-Species Alliances

Ayesha Tan-Jones, Dream Portal Sigil Stones (2021). Exhibition view: Bodies of Water, 13th Shanghai Biennale, Shanghai (17 April–25 July 2021). Courtesy Power Station of Art.

Following 'A Wet Run' and 'An Ecosystem of Alliance', a series of projects, happenings, debates, and workshops forming the first two phases of the 13th Shanghai Biennale, the final phase of Bodies of Water officially launched on 17 April and will run until 25 July 2021.

No doubt this will be a historic iteration of a Biennale that has always offered a vantage point for contemplating the era's questions. Only days before the main show opened, modestly titled 'An Exhibition', the Japanese government announced that wastewater from Fukushima's crippled nuclear reactors would be gradually released into the ocean. News from South Asia was just as terrifying, with mammoth congregations like the Kumbh Mela turning India into the world epicentre for Covid-19 overnight.

The current crisis spanning the South Pacific to the Ganges gives the 13th Shanghai Biennale's culminating exhibition a prophetic yet realistic undertone. An exhibition exploring bodies of water is perhaps the most fitting framework through which to think about the fluid interdependency that defines the times. Even commonplace expressions defining Sino-globalisation—like 'the collective fate of mankind' and 'neighboring across a narrow strip of water'—don't seem to be at odds with the Biennale's hydro-logic.

Compared with the volume and density of previous editions, this 'epilogue' of a three-part Biennale conveys a sense of thematic 'dilution' among works by 64 artists, among them 33 new commissions. Throughout, the notion of water reoccurs in distinct, sometimes parallel manners, forming an organic system of associations instead of a bland repetition of themes.

Entering the first floor, a passage from Canadian gender studies scholar Astrida Neimanis' essay 'Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water' sets the tone, while statements and fragments taken from Biennale reader are dispersed around the exhibition space as vinyl wall texts like a backing track.

The whole show departs from the first work on view. Water System Museum (2018) is an installation by Cao Minghao and Chen Jianjun that focuses on the Dujiangyan project, an ancient irrigation system in Sichuan. Composed of archival material and video documentation, this long-term research project explores the Dujiangyan master plan as framed by Mao Zedong's famous quote, 'Hydro-irrigation is the lifeblood of agriculture.'

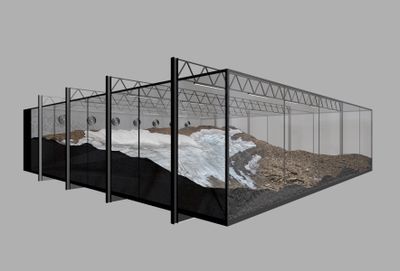

Michael Wang's 10,000 li, 100 billion kilowatt-hours (2021), considers a more recent hydroelectric project. Contained within a refrigerated glass and steel terrarium is a recreation of the Qinghai mountains, the source of the Yangtze River, which feeds the Three Gorges Dam, one of the largest hydroelectric power plants ever built, whose construction uprooted around one million people.

Here, water becomes an artificial entity—a manifestation of man's victory over nature, not to mention state power. Traces of Escapees (2021), a four-channel film installation by Cooking Sections that forms part of the ongoing CLIMAVORE project, traces the impact of pollution on marine life and the environmental implications of fish farms.

As part of their participation, Cooking Sections urged the Power Station of Art café and the restaurant Urside to replace farmed salmon from their menus with a CLIMAVORE dish instead. As explored in the multi-media installation Salmon: A Red Herring (2020), currently on view at Tate Britain, the farmed salmon's signature pink hue is not a natural endowment but the result of genetic manipulation to appeal to human tastes (or perhaps shape their consumptive habits).

On the second floor, rock samples taken from hundreds of metres below Shanghai and Anhui make up Carlos Irijalba's site-specific work Amphibia (2021). Clay from the Yangtze River Delta is laid out in cylindrical sections, turning the gallery floor into a floodplain where muddy water will evaporate and transform as time goes on.

A sense of time passing is expressed, too, in Cecilia Vicuña's towering mix-media installation using raw wool, titled Quipu Menstrual (Shanghai) (2006/2021). Resembling an umbilical cord descending from the ceiling, the artwork is inspired by the ancient Andean quipu method of tying knots into string to record information. Vicuña equates this with water's recording of history and memory, linking to her past activism for Indigenous water rights.

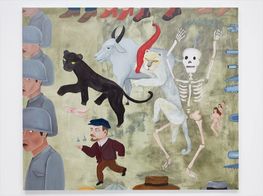

The interactive video installation by Ayesha Tan-Jones—a model who once protested on a Gucci runway with the message 'Mental health is not fashion' written across her palms—is a sight for sore eyes. Dream after Screen (2021) is part of the video series 'Where is Una Jynxx?', in which the artist's alter-ego, Una Jynxx, imagines an alternative universe where new eco-conscious narratives might arise.

Placed in front of the screen is Dream Portal Sigil Stones (2021): an arrangement of three soil mounds from which a twisting of gnarled roots emerge.

Together with works like Pepe Espaliú's performance video Carrying (1992), Ana Mendieta's videos Flower Person, Flower Body (1975) and Silueta de Arena (1978), and Dai Chenlian's video recording, Waxing and Waning of the Augustness (2020–2021), Tan-Jones's installation extends the discussion of 'bodies of water' further to the realm of bodily referentiality that is feminist, queer, posthuman, and supernatural.

Utterly intriguing is Fluffy Grounds (2021), a short video essay on catkins—a seasonal menace common in Northern China consisting of swarms of poplar pollen, known as 'spring snow'. Produced by C+ arquitectas, an architect duo interested in spatial design, the work effortlessly shifts its visual narrative between video and wordplay, in which experimental storytelling and research forms an exploration of urban and technological transformations that are both caused by and the result of catkins.

Fluffy Grounds brings to mind Liu Chuang's single-channel video BBRI (NO.1 of Blossom Bud Restrainer) (2015), not shown in the Biennale. The video delves further into the annual catkin 'snowfall' using found footage pulled from the internet. Scenes include tree-lined streets with white mounds at the base of tree trunks, most likely poplar and willow trees grown within urban landscapes through selective cultivation.

BBRI's humorous and poetic take on the word 'fluffy', which makes for truly enjoyable viewing, was missed in this exhibition, after a string of tiresome encounters with works that are equivocal vis-à-vis the theme.

There is certainly no shortage of empirical rigour in this curation. The Biennale includes loans from the Shanghai Science & Technology Museum, Shanghai History Museum, and Shanghai Workers' Cultural Palace, which add to the historical richness of the exhibition. Among them are the manuscript of Shanhaijing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), models of sand dredging vessels, sedimentary rock samples, and a Qing dynasty dredging device.

As a whole, notes chief curator Andrés Jaque, the intention is to elucidate how Shanghai as an 'ecosystem' mobilises trans-species alliance from a historical and cultural perspective.

Heather Phillipson's Music for Rats (2020) extends Jacque's point. Occupying an entire room, pink fluorescent light illuminates oversized sketches of rats on paper and cardboard as a gentle melody fills the space. As Covid-19 continues its rampage, the legacy of the plague as a bygone terror seems to have little relevance in public discourse nowadays. Phillipson implores us to look at rats with tenderness—as natural beings with equal significance as humans. (Humans, after all, can be vectors and threats, too.)

I end my tour of Bodies of Water at the floor-to-ceiling window overlooking the Huangpu River on the third floor. Here, Neimanis' invitation to imagine ourselves as bodies of water in order to learn how to 'attend to all bodies of water, as they attend to us' comes to mind, as an invitation to rethink the calamities unfolding around the world, as well as those that await us. —[O]