The political present: The Armory Show 2017

The Armory Show. Courtesy The Armory Show. Photo: Teddy Wolff.

What does an international art fair look like in the age of Trump? If this year's Armory Show (2—5 March 2017) is anything to go by, the answer is that it looks very much the same as before. Anyone expecting politically engaged work in this time of deep uncertainty for the United States and the rest of the world would have been largely disappointed. For most of the dealers, things were very much business as usual, despite the fact that the fair's new executive director Benjamin Genocchio and his team did their level best to shake things up. (This is Genocchio's second fair, but last year's was pretty much a fait accompli when he took up his role.)

The fair continues to sprawl across 250,000 square feet on Piers 92 and 94, which stretch into the Hudson River on Manhattan's Upper West Side. But architectural firm Bade Stageberg Cox was brought in for The Armory's 2017 edition to give the layout a complete redesign. This was a success, with the fair now feeling like a suite of interconnecting rooms rather than a huge, brightly lit tent. Genocchio also changed the way space was divided up, knowing that international art fairs of this scale (and somewhat modestly The Armory Show claims to be 'New York's premier art fair') need to be partitioned in one way or another if only to overcome visitors' viewing fatigue.

There were 210 galleries showing at the 2017 Armory Show and Genocchio split them into five sectors. To begin with, he blurred the division between the contemporary and modern sections. Between 2009 and last year, these two sections had a pier each. This year, the 37 galleries that showed only work made before 2000 (the 'modern' galleries) were given a section called 'Insights', which occupied a little over half of Pier 92. To be frank, this was the least stimulating part of the fair, though if you were looking to buy a de Kooning for example, an Alex Katz, or a Joseph Cornell box, you would have found several options on offer. Still, there were signs of political life. The Jonathan Boos gallery had an excellent booth devoted to the African-American painter Jacob Lawrence (1917—2000), titled Jacob Lawrence's Dynamic Cubism. Presented here was a full-blown retrospective with 17 paintings charting the development of Lawrence's brightly colored portrayals of black American life, complete with a scholarly catalogue. It is dispiriting to reflect that in 2017 such an exhibition should take on an air of political audacity, but under Trump's administration it unfortunately does.

Galleries with a more contemporary focus—and with more than 130 booths this is by far the largest section of the fair—took up almost all of the remaining space on both piers, as part of a sector referred to, somewhat anticlimactically, by the simple title 'Galleries'. This was the section with the crowd-pleasers that maintain The Armory Show's reputation as a not-to-be-missed destination for New Yorkers who like to think of themselves as on the cultural front edge. Pace Gallery (which in the past has tended to confine itself to showing examples of its peerless roster of senior contemporary artists—Kiki Smith, for example, or Claes Oldenburg, or Chuck Close), showed an impressive site-specific installation called Drifter (2017) by the art partnership Studio Drift: a huge concrete block (16 x 8 x 8 feet) hanging in the air.

Political engagement was not altogether absent from the Galleries section, though you had to go looking for it. Most of it was found in the booths of galleries where political art has always been a staple. For example, the estimable Jack Shainman Gallery has maintained the implicitly political stance of championing artists from Africa and East Asia along with the work of US artists of colour since it was founded in 1984. The gallery presented a splendid booth that included work by Malick Sidibé, Kerry James Marshall, Carrie Mae Weems, and two examples from Nick Cave's series Hustle Coat (2017). Each of these features a trench coat suspended from a bronze hand attached to the wall. The coat is unbuttoned and opens to reveal a sparkling array of watches, chains, necklaces, bracelets, heavy medallions and charms. Cave's subject here is racial stereotyping, touching on the taste for bling in hip hop culture, but also on the criminals who offer stolen or counterfeit goods concealed in the linings of their coats. They are powerful and typically eloquent pieces.

Paris-based gallery Suzanne Tarasiève dedicated its booth to the work of Recycle Group (Russians Andrey Blokhin and Georgy Kuznetsov), who use (and often repurpose) contemporary industrial materials to mimic the appearances of ancient artefacts. For Recycle Group, the contrast between new and old rarely reflects well on our present-day culture, and they use it to telling political effect. That does not mean that their work is without poetry. The standout piece in their show was the eight-foot-long Tree 1 (2016), which looks like it might be a remnant from some distant shipwreck. The United States motto E PLURIBUS UNUM (out of many, one) is cut clear through the old wood, but as if to call its meaning into question, the last two letters of UNUM are almost illegible at the split and broken end of the wooden beam.

Another Armory Show change is that the 'Focus' section—which first appeared in 2010 and which, until last year, had been a less than compelling attempt to draw attention to the artists and/or galleries of a country or geographical region—has been revivified by turning it over to a curator with a theme. This year's curator was Jarrett Gregory, formerly assistant curator at Los Angeles County Museum of Art and now curator at The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. She titled her politically charged section What is to be Done? and put together the best part of this year's Armory Show, with artists including Teresa Margolles, represented here by Zurich's Galerie Peter Kilchmann. Margolles' deeply affecting installation Karla, Hilario Reyes Gallegos (2016) features an eight-foot-high black and white photograph of a transgender woman called Karla, a 64-year-old sex worker, which Margolles took in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico in July 2015. On the wall next to the photograph is Karla's death certificate bearing her given name, Hilario Reyes Gallegos, and dated five months after the photograph was taken. A soundtrack carries the voice of another sex worker describing Karla's murder: apparently she was beaten to death and discovered half naked in an abandoned building. The final shocking component of the installation is a rough concrete block found at the scene of the murder. It is very possibly the murder weapon.

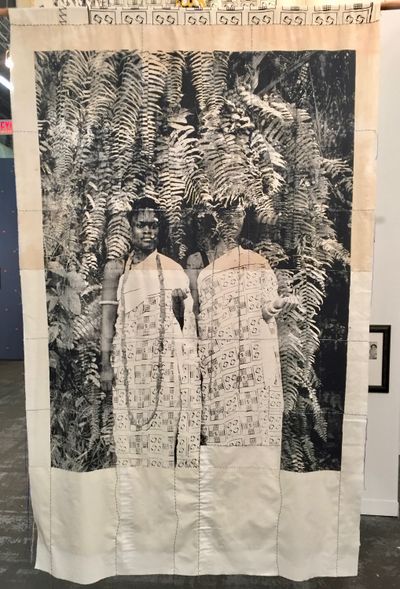

The 'Presents' section is for newer galleries—in business for no more than a decade—to stage solo or two-person exhibitions. There were 30 booths in this section, the best of which was Unraveled Threads featuring the work of German-Ghanaian multimedia artist Zohra Opoku and presented by Seattle's Mariane Ibrahim Gallery. Opoku screenprints images on sheets of cotton and canvas which she then stitches together, embroiders with traditional Ghanaian patterns, and hangs on the wall or from wooden poles. Opoku was born in Communist East Germany, and her father was an Asante monarch who returned to Ghana shortly after her birth. She has no direct memory of him, but when she was able to visit Ghana (she now lives and works in Accra) she met her younger siblings who had grown up there and was able to piece together a narrative of his life. One of her hangings Debie (2017) shows her standing alongside her sister who stares defiantly out at the viewer. By contrast, Opoku's own face is obscured by the leaves of a tree, as though to reflect her deep uncertainty about whether she belongs in a place, or a culture, that is very different from the one she grew up in. Opoku's subject, then, is her own complex family history, and the experiences of anyone with multiple, overlapping heritage. This excellent installation was awarded the inaugural $10,000 Presents Booth Prize supported by the Athena Art Finance Corporation.

Entirely new in this year's Armory Show was a section called 'Platform', curated by former director of the Andy Warhol Museum and now senior vice president of Contemporary Art at Sotheby's, Eric Shiner. The 13 pieces he selected were scattered around the fair and, acknowledging that his role was to break up 'the all-too-familiar monotony of the art fair experience', he described them in his curator's statement as pieces 'that make the viewer take pause, think, refresh, smile, and remember that art, by its very nature, is meant to provoke, incite and challenge.' He did not altogether succeed in that ambition, but he provided at least one more crowd-pleaser: the much-beloved Yayoi Kusama's vast Guidepost to the New World (2016). Seeming to dip in and out of an AstroTurf floor covering, her 16 signature polka dot biomorphs provided a shiny happy diversion for visitors who perhaps needed a break halfway down Pier 94.

Far more significant, and indeed one of the more compelling political works in the entire fair, was the Platform sector's Abel Barroso's Emigrant's Pinball Machine (2012) which was up on the Pier 92 mezzanine. This is an installation of seven slightly undersized pinball machines handmade from rough timber and painted in a cartoonish manner with black paint. Barroso lives and works in Cuba and his subject is how dependent an emigrant's fate is upon pure luck. In one machine, the emigrant progresses simply from the south to the north; in another, an airport immigration hall is represented as a daunting obstacle course; and in a third the emigrant gains experience in border crossing. In all of them of course, the outcome is dictated by where a rolling wooden ball finishes up.

So, what would President Trump make of this edition of The Armory Show? If works of art are simply regarded as a particular—and particularly expensive—category of luxury goods, which is apparently how many of the fair's dealers and visitors regard them, then presumably the president would have had no problem with a fair of this kind. Art changing hands for sums of money, way in excess of what they cost to make, can only be good for the economy, after all. But if art encourages its viewers to stop and think, particularly about issues of race or gender or cultural and national identity, as was the case with a number of booths and works on show, then the man in the White House might not have approved. To this end, perhaps there was good reason for the balance The Armory Show struck between politics and business in 2017.—[O]