The scene of a crime: Shanghai art week 2016

Installation view, OVERPOP at the Yuz Museum. Image courtesy Yuz Musuem, Shanghai.

Due to a grave scheduling error, one of China's biggest contemporary art weeks coincided with this year's American election. At the first preview of the West Bund Art & Design Fair in Shanghai on Tuesday morning, election updates were sporadic on my firewall-blocked phone. Yet contrary to the morning's prediction of a Democratic win, red encroached on blue on the electoral map and soon confirmed Donald Trump as the next president of the United States.

With much of the world in a state of alarm, countless think-pieces have been published in the weeks following Trump's surprising ascent to the White House, outlining the devastating implications his presidency may have on women, Muslims, immigrants, minorities, social rights, foreign relations and climate change efforts. A longtime critic of Trump, Paul Krugman of the New York Times wrote, 'it's a disaster on multiple levels, and the damage will echo down the decades if not the generations. And like anyone on my side of this debate, I keep feeling waves of grief'. When the news broke that Vladimir Putin had reached out to congratulate Trump immediately, I began to wonder what the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire had looked like. Did the Romans see it coming?

Yet the overall atmosphere of the art fair in Shanghai that day did not seem as frantic as I. Save for subdued murmurs, business carried on as usual in the country that Trump has accused of inventing global warming and robbing his own of its rightful prosperity; too much money was at stake to let the news compromise momentum. Frankly though, I couldn't concentrate: a trade fair seemed trivial as social and political progress seemed on the brink of a steep and painful descent. But then a light caught my downcast gaze. In White Cube's booth, Tracey Emin's neon I Cried Because I Love You (2016) (ubiquitous in the art fair circuit over the past year) abruptly adopted a new meaning beyond its initial reading. Encountered in that moment, Emin's addressed lover was replaced with the generation of American children who will grow up with a leader who normalises sexual violence and mocks the disabled.

The beloved was replaced with Hillary Clinton, who, in the words of Lindy West, 'swallowed slander and humiliation and irrational hatred for three decades and she didn't quit, and here she was, just a hair's breadth from the presidency of the United States—the first woman ever to be trusted with the rudder of the world'. The once almost saccharine sentence provided solidarity in a time of grief. Art, as we can often count on it to do, became applicable again. Yet meaning—as it also often is in an overwhelming time—was coloured by a greater context.

The third edition of West Bund Art & Design was held in a former manufacturing facility in a riverside area previously zoned for heavy industry. Over the past few years, the West Bund district has been rapidly rebranded by the government as a cultural corridor and a centrum for the city's explosion of private museums and galleries. Founded in 2014 as part of this initiative, the West Bund fair is notably also a state-owned entity. This was evident from the outset: inside the fair's front doors, scale models of future art institutions aimed to affirm the zone's cultural importance. With only 30 galleries participating this year, West Bund is small on the spectrum of international art fairs, and thus refreshingly digestible; it was possible to see the entire fair within two hours.

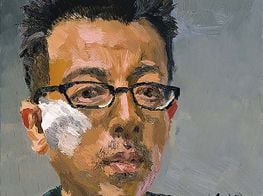

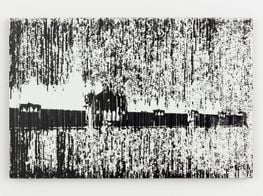

Appreciation amongst attendees for the tightly curated and manageable event was widespread. In addition to strong galleries from China and greater Asia, the fair also attracted Western participants including David Zwirner, Hauser & Wirth and Pace Gallery. Hong Kong and London's Massimo de Carlo Gallery also presented three works from politically-minded painter Liu Xiaodong's series of Chinese migrants in Italy, while Galerie Perrotin's booth presented Gregor Hildebrandt (who uses records and cassette tapes as his media) with gratifying inventiveness.

There was much to encounter in the building beyond big paintings and easy-sells. Yet perhaps the most interesting works were found in a branded tent next to the fair: Xiàn Chǎng, West Bund's curated section, was organised by Mark Rappolt and Aimee Lin of ArtReview Asia. Translated from Chinese, the title means 'the scene (of a crime, accident, etc)'; (on) the spot; (at) the site. Fittingly, that was exactly how the world felt that day. Outside the entrance, Liam Gillick's commission 128th floor... (2016) echoed the arrogance on the airwaves. Having discovered on Wikipedia that the tallest skyscraper in Shanghai currently reaches 127 storeys, Gillick turned the tent into an imagined 128th floor by applying an enormous table to its exterior. Not only was this a reminder of Trump's wild exaggeration of the height of his own towers, but it was also evocative of the frenzied construction race in China and the concomitant pomposity of size.

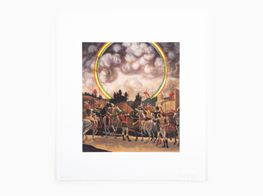

Inside, a screening of Laurent Grasso's cinematic film Soleil Double (2014) depicted two eerie suns burning over a city district of Rome. Continuing in Grasso's examination of the aesthetics of power, the imagery also alludes to far-fetched climate manipulation conspiracy theories. Further along, 'multinational brand posing as an art-project posing as a multinational brand posing as a biennial' Shanzhai Biennial contributed Shanzhai Biennial No. 2: Dark Optimism (2013–16), an LED video installation in which an actress lip-syncs to a Mandarin rendition of Sinead O'Connor's Nothing Compares 2 U. According to Rappolt, the lyrics had been translated back and forth from English to Mandarin until they had become meaningless. Behind the video screen, a mannequin clad in a sequinned dress patterned with Head and Shoulders shampoo packaging referred to the disjunction of meaning that occurs when western brands are mimicked by Chinese factories.

Next door to the fair was ShanghART Gallery's new West Bund space, inaugurated with the exhibition Holzwege (9 November 2016– 15 February 2017). Curated around Martin Heidegger's term 'holzwege' which describes an overgrown, rarely trodden forest path, the show includes works by both non- and Chinese artists—including Zhang Enli, Jörg Immendorff, Shao Yi and Apichatpong Weerasethakul—seen to be groundbreakers in their respective mediums. A topical and resonant series on the ground floor was Yu Youhan's 5 Women (2001): five large-scale paintings of female faces painted in the same sombre, dark blue and black palette. Nearby, Martin Creed's solo exhibition Understanding was opening at Qiao Space, a small private museum recently opened by Shanghai collector Qiao Zhibing.

Qiao, who made his fortune in nightclubs for which he began collecting art to adorn, inaugurated the space this September with the untraditional exhibition Studio, focusing on the practices of 12 well-known contemporary Chinese artists. However, rather than presenting artworks, the exhibition housed tokens of the artists' studio practices in the form of photographs, ephemera and documentation. A notable inclusion was that of painter Ding Yi, who in lieu of providing a physical object, allowed organisers to drill a hole in the gallery wall adjacent to his studio so visitors could observe him at work.

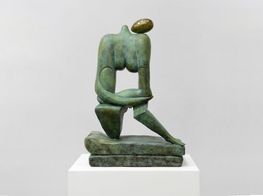

Down the road, and now in its third year of operation, Chinese-Indonesian collector Budi Tek's Sou Fujimoto-designed Yuz Museum is exhibiting the Jeffrey Deitch and Karen Smith-curated show OVERPOP (4 September 2016–15 January 2017) presenting a sample of contemporary art aesthetics from in China and abroad, OVERPOP includes pop-influenced work by 20 artists including Ian Cheng, Alex Israel, He An, Wu Di and Borna Sammak.

For Smith, if pop's aesthetic critique has been overtaken by the new generation, 'then China presents an interesting comparative case study' for its artists confronting the politics of the Internet and display. The exhibition is a particularly pertinent one for international viewers to visit, as the young Chinese artists included came of age during China's era of rapid urban and economic expansion.

Notable inclusions are Tan Tian's saturated acrylic and sticker paintings You are so damn beautiful tonight and You can see something which others can not see (both 2016), Camille Henrot's endearing paintings of life's small humiliations, aaajiao's abstract sculptures inspired by Windows software, and Samara Golden's mirrored installation The Flat Side of the Knife (2014).

At MadeIn Gallery, further along the road, the exhibition-shop 'Xu Zhen Store' (5 November–12 December) offers editions of the eponymous artist's sculptures, furniture and clothing for relatively affordable prices. Commerce is often braided so deeply within the art scene in Shanghai that this tongue-in-cheek retail initiative could easily be missed as a commonplace occurrence.

Down the river, collector Liu Yiqian's Long Museum West Bund had extended the dates of SHE: International Women Artists Exhibition, which included works by 105 women artists from 13 countries selected from the museum's collection and supplemented by loans. The show was curated by Wang Wei (also the co-founder of the museum) who suggests that historically, female artists have been underrepresented in China partly because of societal pressure and familial duties.

The references to femaleness in the works ranged from outright to subtle: against a slate-grey wall, Jenny Saville's fleshy oil painting Shift (1996–7) depicted six nude figures rendered with a noticeable absence of a sexualised male gaze, while in the centre of the room, Yoko Ono's freestanding spiral staircase To See the Sky (2015) invited viewers to climb it until reaching a dead end at the top. The experience of this work was a sharp reminder of meaning echoed by context: parallels were easy to draw between the unsteady wavering at the apex of the climb and and shakiness of women's still-limited political ascent.

In the video room, Cao Fei's LA Town (2014), a film of an imagined post-apocalyptic city with Italo Calvino influences matched the impending political unease. Long Museum founder Liu (famed for his 2015 purchase of a US $170.4 Modigliani), was recently profiled in a New Yorker article which looked at the recent boom of Chinese museums with a critical eye. The quickly built institutions, modelled after major western counterparts, are often lamented as lacking academic rigour, professionalism, adequate conservation strategies or proper educational programming. Of the exhibition SHE, author Jiayang Fan wrote in the article, 'individually, the pieces were interesting enough, but their placement seemed haphazard, as if movers had plunked them down in a warehouse'.

The eventful week also marked the fourth edition of contemporary fair Art021 (11–13 November), held at the grandiose Shanghai Exhibition Center. The fair had a remarkably more commercial atmosphere than West Bund: booths selling jewellery, luxury cars, and champagne were prevelant. A baffling and highly-publicised display of paintings of fish by Adrien Brody was situated at the fair's entrance. Despite the contrived glamour, some booths showed strong presentations, noticeably Gagosian's with its hang of Cecily Brown paintings and Leo Xu Projects, with its display of Liu Shiyuan's search-engine generated wallpaper As Simple as Clay (2013).

Galerie Perrotin (having a great week in Shanghai) had another strong booth featuring works by Bernard Frize, Gao Weigang and Park Seo-Bo. In Jae Yong Rhee's series Memories of the Gaze in Gallery EM's booth, photographs of abandoned rice mills were a reminder that the disappearance of manual labour jobs is felt universally. This was particularly pertinent that day: contrary to the American president-elect's claims, the loss and migration of manufacturing jobs is not solely felt by America or is it the fault of Chinese thievery. Rather it is a side effect of worldwide industrialisation, technological advance and globalisation. Other booths at Art021 were rather one-note, commercial hangs, banking off visually-driven buyers. A fair is only as strong as its weakest booth, and Art021 and its better participants would benefit from a more discerning gallery selection process.

As an intellectual counter to the capitalistic events of the week, the 11th Shanghai Biennale (12 November–12 March 2017) launched at the Power Station of Art. Curated by New Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective (Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula and Shuddhabrata Sengupta), the biennale was organised under the overarching question, 'Why Not Ask Again?' Spanning three floors, this biennale has been received as one of the finest this year. With allusions to futurism and science fiction, all writing surrounding the exhibition (press releases, brochures, wall texts) descriptions is open-ended and poetic, paralleled by the theatricality of the programming that surrounds it. In the spirit of accessibility, the curators have organised 'Theory Opera' performances within the exhibition space in lieu of esoteric conferences or panel discussions. In their words, the initiative shifts 'the sensory and auditory rhythm of walking, stopping, resting, chatting and looking.'

Despite this effort towards democratisation, a film by Chinese artist Sun Xun was pulled by the Shanghai Cultural Bureau in an act of what seemed to be state censorship. The work, Some Actions Which Haven't Been Defined Yet In The Revolution (2011) was replaced by a sign reading 'The work is unable to be shown as part of the exhibition due to non-technical reasons'. Apparently while some inquisition is accepted, asking too much is ill-advised.

It is important to consider the presence of a biennale within the context of Shanghai's aggressive urban development. A biennale reaffirms a city's status as a cultural capital, which as evidenced by the hyper-development of M50 and the West Bund cultural corridor, is one that is important to Shanghai's municipal government. Art is an often turned-to catalyst for economic growth and gentrification, yet its results always come with a cost: tenants and residents of developing areas are evicted and pushed further to the fringes of cities as the cost of living rises. While Raqs Media Collective mounted a fascinating and intellectually rigorous exhibition, the Biennale must always be conscious of its context as an art event in a city that is fast rebranding top-down. Especially in a major Chinese city like Shanghai, it is always crucial to remember where the money is coming from.

By the time I arrived at the Felix Gonzalez-Torres exhibition at the Rockbund Art Museum (30 September–25 December), I was feeling worn down. It wasn't only the privileged exhaustion of one who has been running about during an art fair week, but rather an emotional fatigue as a result of the past days' political events. Housed in the former Royal Asiatic Society, the Gonzalez-Torres exhibition was curated by director Larys Frogier and senior curator Li Qi, who together were tasked with presenting the late artist's works in a major Chinese exhibition for the first time. Sensitive consideration for the historical building's architecture was evident: a familiar long string of lights dangled several storeys long in a stairwell—each bulb representing a life which will eventually flicker and burn out. A curtain of gold, shimmering beads hung down three floors, evoking the dancer who performs on a stage for five minutes each day on Untitled (Go-go Dancing Platform) (1991) upstairs. As visitors plucked multicoloured candies from Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), the pile's diminishing size represented the way that Gonzalez-Torres' lost lover, Ross Laycock, wasted away until he eventually died of complications from AIDS. Downstairs in the gift shop, the two clocks of Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1991) ticked faithfully in sync.

Touched with love, melancholy and despair, Gonzalez-Torres' emotive works are memorials to those lost to the AIDS crisis which ostracised American queer communities, now again unsure of how their government will protect them. The artist's penchant for making intimacy public is epitomised by the installation Untitled (Loverboy) (1989), which simply consists of blue curtains hung over the gallery's windows. The light streaming through creates an intimate, blue glow reminiscent of a male bedroom; looking at it is like pressing on a gentle bruise. In the blur of art fairs, biennales and exhibitions, it is easy to avoid looking with sensitivity. However, there are times that art should knock you out of your education and nudge you towards heartbreak. The socially engaged, political work of Gonzalez-Torres (who himself died of AIDS at 38), is a fine example of a practice that should be viewed with an openness to affect—a rare and generous act in the world of contemporary art.

Conservative media outlets have been mocking the public grief of liberals post-election, calling Trump protestors 'whiners' and 'babies' as they voice their anguish. Yet the concerned have the right and a duty to express their alarm—it is an inalienable right of citizens of free states. If no one piped up in the face of bigotry, how long would it take until racism, sexism, and xenophobia feels natural, or until news outlets report on it as if it's not vile? How many questions are too many? In a post-truth era, it is crucial to never stop talking about what is problematic lest the conversation die.

By and large, the American art world was heavily invested in the election. And in the weeks since, the community that champions subjectivity, identity politics and difference has come out in droves to protest the results. Can all of this energy be used for good? I believe so: let's inject some feeling back into the art world. Put the poetry back into looking. Abandon the artspeak. Talk so people can understand. Why not sing about art like an opera? In their biennale curatorial statement, Raqs Media Collective expressed hope of producing "a storm of desires in your heart." Surely that storm continues to blow in many of us. Two days before the election: queer poet Eileen Myles performed a presidential acceptance speech in front of Zoe Leonard's I want a president (1992) on the Highline in New York:

'First I want to say this feels incredible. To be female, to run and run and run to not see any end in sight but maybe have a feeling that there's really no outside to this endeavor this beautiful thing... Dance now. I love my fellow citizens. It is good to win. Thank you... See the see the see all of your fabulous beauty and your power and your hope. Thanks for your vote. And I love you so much thanks.' —[O]