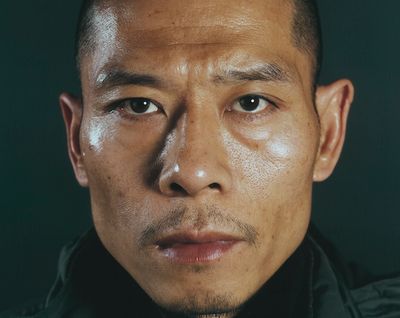

Zhang Huan At Carriageworks, Sydney

Image: Courtesy Pace Gallery

Standing before Zhang Huan's Sydney Buddha—considering the grace and serenity of the five-meter-tall Buddha's decidedly feminine repose—I can't escape the fact that the foyer of Carriageworks, in which the Buddha has been recently installed, stinks. Something has died here and then dried in the summer sun.

The mercury is stretching up towards the mid thirties; the staff will have to find the source of the smell and then bury whatever they find — and soon. The artist is due to arrive.

It's a fitting surround in which to consider the latest work of Zhang Huan, one of China's most acclaimed artists, who first gained attention as a malodorous provocateur. In 1994, Huan covered his naked body in fish oil and honey and sat—in a similar pose of rectitude as the Sydney Buddha—in a public toilet in Beijing. Flies gathered and crawled over his wet, fetid body. Huan wasn't doing anything shocking; this, he said, was how most people in the city were made to live. The work, 12 sq. metres, was made to draw attention to the state of public sanitation in Beijing and the image of the peaceful, fly blown artist became iconic.

Moments before Huan arrives, I realise that it's not the space, but rather the art that stinks. Made from 20 tonnes of incense ash collected from Buddhist temples in Shanghai, and the Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces of China, Zhang Huan's Sydney Buddha is literally composed from the prayers of millions of people. In Chinese Buddhist practice, ash is traditionally considered a sacred object, a critical mass of devotion that is left untouched. Aware of the reverence given to ash, Huan makes donations to the temples, which in turn allow his assistants to collect the ash and cast it in the shape of the deity it was burnt to entreat.

Huan's latest series of works, including iterations of the Buddha in Germany and Italy, seem a change of pace for an artist whose work was decidedly radical in China, often involved public nudity, and worked to express the frustrations of those living in the shadows of power. The question of the apparent relaxation in his work is answered with the truism that in a lifetime the only certainty is that we will not stay the same. "There is nothing that never changes", responds the artist sagely, noting that an awareness of change is fundamental to Buddhist practice and, in turn, to a life. Though age might not have wearied Huan, it has brought it with it the privilege of quieter reflection, a studio the size of an airplane hanger and over 100 assistants to direct at will. It might be the case that the now famous artist prefers to indulge in demonstrative works of scale, rather than vulnerable works of protest.

Though titled in the singular, Sydney Buddha exists in plural. The work is in fact two Buddha's; with the ash Buddha resting opposite the aluminium body from which it was cast. On the day I visit the work has just been completed and the artist is directing a delicate choreography between two assistants on a cherry picker who are readying the removal of the aluminium supports that bolster the ash. Eventually the ash Buddha will degrade, and large pieces will fall to the floor. "I hope that the Buddha can bring hope and happiness to this city and its people," the artist announces over the beeping of the cherry picker. "A city so beautiful, happy and free. I love it," he says. Huan says he doesn't privilege art or Buddhism in his work, instead he allowing it develop besides the categories of art and religion, as an extension of his understanding of the world "It's my life." he says of his art. "But first of all it's an expression of my belief." Each of Huan's Buddha's have been made as a personal expression of public optimism, they are in themselves offerings to the cities in which they are shown.

"I've been following Huan's work for some time," says Carriageworks' director Lisa Havilah. For Havilah, the fit between the Chinese artist and the Australian venue was natural and indicative of a shared optimism between cultures. "One of the things that we are focused on at Carriageworks is the presentation of international work from Asia and the Pacific in order to reflect the social and cultural demographic of Sydney. Sydney Buddha fitted into that ethos really nicely."

In describing the collaborative process between him and his assistants, Huan says, "We work in the same way as a factory but with a creative difference; we are making a unique piece. The whole studio follows one concept, directed by me and carried out by each assistant." I ask if this level of production and assistance facilitates the creation of large-scale rather than intimate and handmade work. "But the work is handmade," insists his assistant and translator. "Yes," I offer, "handmade by hundreds." Huan uncrosses his legs and looks ready to leave. "Even Michealangleo needed help," he says.

Though Huan's Sydney Buddha contains "the collective souls, memories and prayers of the faithful," I'm left feeling a little cold by the artist's intimations of subject and emotion. I search for the remains of something unique or personal in the burnt ashes of a million anonymous prayers and find that Sydney Buddha is a work of existences rather than existence, representative of a culture united in sufferance, a symbol of a collective rather than a fluid identity. For Buddhists, every image of Buddha stands at the end of a succession of images reaching back to the Buddha himself—a hall of mirrors precede the unattainable being. Perhaps Huan's large-scale installation loses a power at the juncture of East and West, becoming stuck between states of perception, flitting between edifying being and aluminium-cast caricature.

As half of the ash Buddha falls to the floor to be trodden on and walked out the door into the streets of Redfern and to the city beyond that, a pervading odour of charcoal and mildew remains. It is the smell of millions of people, crowded together, the smell of human hope.—[O]