Angela Bulloch at Simon Lee Gallery, Hong Kong

Having graduated from Goldsmiths, University of London in 1988 and shown in Damien Hirst's seminal Freeze exhibition of the same year, the Berlin-based artist and Turner Prize nominee (1997) Angela Bulloch has made experimental breakthroughs in painting, installation, sculpture and mechanics throughout her 30-year career.

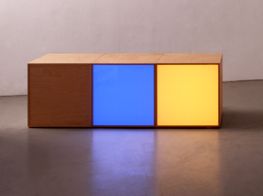

Installation view of Angela Bulloch, One Way Conversation..., 2016 at Simon Lee Gallery, Hong Kong. Photo: Kitmin Lee. Courtesy of Simon Lee Gallery.

Canadian-born and UK-raised, Bulloch is perhaps best known for her stacked and electronically-lit 'pixel boxes' which softly change colour according to programmed rhythms. Fabricated from plastic or metal, the cubic works are formally linked to minimalism while also functioning as sorts of cybernetic monochrome paintings. Bulloch is also recognised for her 'Drawing Machines', apparatuses that make marks directly on walls in response to stimuli in the gallery created by visitors.

This year work by the artist has been shown around the globe beginning with a solo presentation at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich (20 February–2 April), and followed by a major museum exhibition in the UAE at the Sharjah Art Museum (9 March–31 May). Curated by Amira Gad and Brigitte Schenk, the two-person show at the Sharjah Art Museum, entitled Considering Dynamics & the Forms of Chaos, paired works by Bulloch with paintings by German artist Maria Zerres.

Most recently the artist is enjoying a solo exhibition in Hong Kong at Simon Lee Gallery (14 October–19 November 2016). Entitled One way conversation... the Hong Kong exhibition sees Bulloch present painted stacked columns of polyhedra, conceived with the aid of computer software. The geometric forms have a direct relationship to the body due to their large size and central placement in the gallery which allows viewers to circle the sculptures, examining their irregularities. Geometric wall paintings in harmonious colours accompany the sculptures, echoing their forms in the space.

Your sculptures have often been likened to totem poles. Formally, this comparison is very clear, but are there other conceptual similarities that they share with totemic sculptures, perhaps in terms of monument or spirituality?

Well, I think now that they go into the world, maybe they're seen that way. One aspect of sculpture which is not pre-given is the context in which it ends up. I think that context is a terribly important thing which you don't know when you make works. I placed them here in this exhibition together with certain wall paintings, so I made very specific choices in this space. These things I can control, but when it goes beyond a gallery, it's a big challenge to find the best places. This is also what gives them meaning. A large work outdoors gives a sense of scale. But it might be taken as a kind of monumentality, larger than life. It could then function in a totemic way. In terms of spirituality, that's a lot more to do with what people bring to it than what I give it.

Do you think that the works are more likely to function as monuments when they're separated or placed together?

This is the way in which the work is passive. It is open to interpretation, in a way.

Are wall paintings something that you make frequently?

I've made wall paintings like this, a lot, in different ways; simply by drawing or making machines that make drawings. I've made a lot of wall paintings using text and different kinds of interpretations of that. The wall paintings in this exhibition are really a reflection of the sculptures, and a kind of friend of the sculptures. They're very much made as an installation in the space. The sculptures come first, the paintings come afterwards.

When looking at your pixel boxes [not included in this exhibition], I'm reminded of the way that film uses light and music to orchestrate emotion. For example, when music swells in a movie, we know we're meant to feel a certain way, or when the lighting conditions shift, we feel another type of response. Is that capacity for affect something that you're interested in when you make the works?

Yes, but it's something that belongs to the Baroque, another time of architecture, or the symphony. It's another kind of production, really. I'm interested in different types of gestures, because I find those sorts that you just described a bit kind of corny. It's sort of like someone showing up with a bunch of roses. It's not really a bad thing, but it's also not going to be it, is it? But that's to do with the wrong image at the wrong time.

What is it?

Well, something that impresses you. An organisation of your reaction to something.

How did you begin making the pixel boxes?

I had to get very technical, that's what I did. It took me quite a long time to find, source, and experiment; it is like a research and development project. In an electronic engineering kind of way. I first produce the module.

Is it something that you taught yourself or did you work with engineers?

Yes, I did teach myself in the beginning. But then I figured that actually I'm not the best at it, and I can definitely get other people to do that for me. I did make my own boards, I did do a lot of work with switching and programming in the sense of really making and choosing what to tell those things to do. So I did the really basic things in the middle of the 80s.

Was electronic art something that was addressed during your education at Goldsmiths?

Well, just in the theoretical sense, in terms of feminism, like what you could understand about how to read the material. For example: this as a material has a gate or doesn't have a gate, and so it's yes or no, and then through very many complicated series of connections between those things, you can produce something which is like a chip in a computer and then you can have another language and you can actually do something with that. It turns from something very basic to something that becomes more and more functional. And that's the development of some digital technology. So I started really in the kind of beginning of that, yes, and I was very much interested because of some studies in feminism. So that is how it began. And then I went and learned how to do some of that myself, I didn't study that at college. I was an artist. I did it anyway.

Why did you decide to go to art college?

I wanted to be an artist, it's a simple answer, really.

Is it natural for you, as an artist to cross over to other disciplines such as industrial and interactive design?

Yes, it is. It is all led by my own curiosity. If you can't find something, and you want to make something, then you've got to make it yourself. And then you find ways in which to conjure the right set of conditions and circumstances and materials. Then, through this really quite messy experimental, extensive approach, then you might find something that is actually something that didn't exist before that you can just then build on. That's how my curiosity leads me, and that's how I do it.

Your work is full of optical illusions. The works in One way conversation... are a great example of that. Do you think that viewers should be disoriented when they're in a gallery or when they're looking at an artwork?

Well I don't think it's a condition of being in a gallery. I think that life is dizzying, and I think if you create that moment of smaller confusion or question or doubt, it can put you in a place where you ask questions too. You question where the ground is. It's something quite fundamental, really.

Given their interactive qualities, can you tell me about the relationship that your works have to play or fun? I'm thinking of the Spotlight with Video Games Sound Box (2010), a projected light that turns off when a viewer attempts to step into it accompanied by the sound of video games, and a 1991 project in which you listed all the entertainments in a shopping and entertainment centre in London.

That's something I did a lot in the beginning, even starting in the 80s and the 90s. Because I've recently shown early works in the exhibition in Sharjah, I've come into contact with them again myself. Normally they sit somewhere else in a box. But I've actually had to engage with those works and place them within a context of other works in a linear narrative. I've had to consider how to situate such works in a way that the people who encounter them will enjoy that. This is a bit of a key thing.

So enjoyment is important.

Yes, but it's not just interactive, it's inter-passive. If you enter a situation and expect to be able to press a button and see a certain result, and that result occurs, then everything is all very straightforward. And actually to me, that's a bit boring. I prefer something else which, is when you don't really expect something, but you walk in and something odd happens. And it takes you a little while to figure out that you might have had something to do with that. That's a much more human situation, because it's not all about the ego, it's about the subtlety of finding one's effect as an echo or as a result. The spotlight piece is a good example because it's an inter-passive thing, because the spotlight is shining on the wall and disappears when you try to get in it, so it's a bit like the inverse.

Do people get very frustrated when they experience it?

No, all the while there is a kind of quite insane gaming soundtrack always going on. It creates doubt.

I read recently that you re-encountered a lot of your works when you moved studios. What was that like?

I mean, it's terrible. It's terrible to move at all, right? Even if it's just your house ... but all the studio, and all the works, and all the things you carry around with you. That's a total reboot and re-filing of your brain and memory and everything to do with your production. It's quite a thing to do. Quite an undertaking.

How do equations and mathematics factor into making your sculptures?

I usually let the computer do that for me. Somethings are randomised. To make sculptures like the ones in the exhibition, there are many calculations that are made. But when you work on a virtual field, in a computer, you can use an easy-to-use software and can translate the sketch into something much more fundamental and precise. You can use an engineering program which can actually produce very precise vectors for a machine to cut material. Those things are then put together by hand.

So there isn't an equation that perhaps you employ for a sculpture which repeats itself?

There are algorithms all the time within programming. Yes, you have to set parameters. Random is a really difficult one.

How was the show at the Sharjah Art Museum received by the audience in the UAE?

That's hard to answer. The exhibition itself in Sharjah was a very strong, linear exhibition. It was arranged in a very long line, with a room here and there and so on. It was like moving on a train where one can watch the landscape of the exhibition to the left and to the right, and then you come back. The museum itself was actually designed by the Sheik [Sultan III bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi] in a very formal way of handling openings. They would make a procession.

Meaning that it's symmetrical?

Absolutely. That was the Sheik who made the sketch. You know, he's done some civil engineering studies himself and he did make the design of that museum. It's very interesting; architecture has to start somewhere.

I found the pairing of your work with Maria Zerres' in Sharjah interesting, especially given the title of the exhibition which referred to chaos. Chaos is very evident in Zerres' paintings, but how does chaos factor into your work?

I spend my life trying to avoid that.

Your work seems very organised.

Well its seems that way because I've reached a point of order. But in fact, it isn't always like that. It's kind of nearly Herculean that it's not. It's this kind of enormous effort. But the title is interesting, I think. I came up with that title together with the curator Amira Gad and it was supposed to be a proposition, a question. It was intended to provoke people to ask 'how do we bring these different forces together'?

Chaos and order.

Well, yes, but these are abstract terms, so also 'the work of Maria Zerres and the work of Angela Bulloch' were being brought together under this title.

It sounds even cooler in Arabic, the translation is very good. There isn't such a word for 'considering', for example in Arabic, so that's what really stands out when you read it. It's very pleasing to people. So linguistically speaking, the title of the show is a provocation to persons going to see the exhibition and who are looking and reading its title in Arabic. It was kind of wonderful to be able to figure out the title with Amira, and then have it translated, and that translation results in a reaction. That was very pleasing. —[O]