Guy Sherwin at Christine Park Gallery, London

I approached Christine Park Gallery from the other end of Riding House Street at around 7 p.m, after dark. It was my first visit and I did not know what would come into view, but from about 50 metres away, it was easy to identify Guy Sherwin's 16 mm film installation exhibition, Light Cycles (13–27 February 2017), as the small window of the gallery had become a backlit screen, catching shadows of the two slowly turning film reels of a projector. This was a visualisation of the title of the show, and a very effective self-advertisement.

Installation view: Guy Sherwin, Light Cycles, Christine Park Gallery, London (13–27 February 2016). Courtesy the artist and Christine Park Gallery. © Guy Sherwin.

Inside the show, Projector Illuminating Itself (2016) is a puzzle or play on the versatility of the film projector as a piece of equipment and its ability to explore and expose itself. A small mirror, strategically placed, reflects the light from the film gate towards a larger mirror just over a metre to one side, which then reflects the beam of light (increasing in size with distance) back at the mechanism, creating a shadow larger than the actual projector reels, turning on the screen in the window beyond. A clear 16 mm film was running, and I was delighted to find that the larger mirror was also a screen where a sharp image of the film in the gate showed dust particles in an animated pattern as the film moved. This mirror/screen could be seen both as a component of the work and a small piece in itself, again referencing the time process and the medium as dust collects on the film during the two-week period of the show.

My private viewing of the installation took place in the hours of darkness, which worked especially well for the window back projection. However, the opening hours of the gallery are eleven to six, which means that most of exhibition was held in daylight. One reason why I returned the next day was to experience the daylight effect. The gallery was blacked out except for low-level diffused daylight that enters through the screen at the front window, but increasingly towards the back of the gallery, the light from the projectors controlled the conditions of illumination.

All seven projector pieces used black and white film, had fixed camera views and no sound other than that of the motor hum and slight film travel clicking of the projectors. Looper systems on top of the projectors, built by David Leister, were almost silent.

A few steps into the long narrow gallery on the left hand wall, we found Metronome #2 (1978). The outlines of static objects on a shelf and their shadows, which appear in the film, were drawn onto the screen. These included the body of a metronome, but at a certain point, the shadow of its moving pendulum no longer traced. It disappeared.

A time-lapse effect showed the movement of a shaft of sunlight across the objects, while the pendulum of the metronome moved from side to side. The movement of the light beam extended the shadows to the right beyond their outlines, and briefly lit up the body of the metronome, separating it from its silhouette. When the beam then revealed the reproduction on the wall as Vermeer's A Lady Seated at a Virginal (c. 1670–72), the thought occured that it was a beam from the same light source that entered Vermeer's room, 300 years ago.

After watching for a few seconds, I was aware of an intensely beautiful moment at the beginning and later again at the end of the three-minute cycle, when the light faded, leaving the moving image of the pendulum just visible among the shadows; the only moving part. During the fading, the relationships between the shadows changed so that there was one point when the pendulum appeared to go behind the shadow of the bottle in the background instead of in front (this was but an illusion). The soft grey painted projection screen helped to create the subtle detail of the shadow values.

There is such a lot going on in this film that makes it interesting. The original time-lapse from 1978 was a bit of a mystery because the pendulum sometimes juddered, while at other times it seemed to move without difficulty but tracking in the correct direction. It never jumped to different places as one would expect from a random interaction with the frame exposure, so I guessed that there was some sort of deliberate intervention linking the timing of the metronome and the camera shooting speed.

Overall, I was struck by the entrance, movement and exit of the light beam: a smooth, strong and very different sort of interval or force to the man-made movement of the metronome. Here the film contrasted the fragile tinkering of human beings in their creation of mechanical time, with the power of solar action: a solar beam that moves through human dwellings and falls on objects outside our scale of time.

At right angles to Metronome #2, on a small wall facing the front gallery window, was Portrait with Parents #2 (1974). The installation consisted of an actual frame on the wall roughly one metre across, with a mirror inside it and a pale grey matte screen central to that. This received the projected film image of Sherwin's parents standing and reacting on either side of an oval mirror in which Sherwin himself can be seen cranking the filming camera; a conversation about the event is going on between them.

In this work, the viewer witnesses Sherwin's mother's reluctance to participate and his father grabbing her arm to pull her back into the frame. The posing, the competitive photography back at the movie camera, the smiling (then forgetting the self-conscious image as conversation took place) all became the revelation of the moment and process of the portrait, expanded and examined by the film itself—unlike a static image portrait, which has only one condensed view or moment.

I realised too that the use of the mirror around the screen was very considered and meaningful, so that the whole set up was a sort of meditation on portraiture, the passage of life, and death. The mirror within the film showed Sherwin as the son and the originator of the film, notably in the process of cranking, recording and exposing what we are watching. Then in the gallery, the installation mirror revealed the viewer—for the reception process was part of the portrait as well.

At this point I felt a strong sense of grief that the viewer is one of many passing portraits. I could look at myself as another face in the installation, but move away, and this would accentuate the issue of mortality, reverberating back and forth between all three portrait layers.

The inclusion of the other more conventional use of mirrors—Sherwin's mother using it to primp her appearance at the beginning and end of the three-minute cycle—was a lighter, more amusing thing; maybe someone in the gallery would quickly adjust their hair in the installation too.

The three installations in the front chamber of the gallery were connected by the lighting conditions, for the intensity of the outside light changed while filtering in through the canvas window screen, and subtle changes in ambient light were cast from the projectors during the loop cycles. The installation mirror of Portrait with Parents #2 also connected with the pieces because when looked at closely, from certain angles, the reflections of the other two installations could be seen.

Walking further into the gallery one found a small chamber to the left, positioned midway between the front and back rooms. It housed a single projection, Eye #2 (1978), shielded from the ambient light of the other installations.

Attention is concentrated upon the changing light of the film. A closeup view of a right eye and surrounding portion of the face looked from the screen in a three-quarter view, across the bridge of the nose on its left towards the camera. The projector is positioned where the eye was looking, referring us back to the camera's position.

This small image occupied less than half of a landscape-orientated black screen in the right hand half, leaving the left half of the screen empty. This emptiness raised a question: was it the other half of the face that goes there? Maybe not, because the other half of the face would be on our right, not left, so what else? Was it the eye of the artist, of the camera, or our own eye—the viewer? These possibilities had been carried over in my mind from the previous installation: Portrait with Parents #2.

In Eye #2, the film brightened and darkened while the framing of the eye remained constant, as did the stillness of the sitter's gaze back into the camera and at us. There is a connection between the eye's pupil and the aperture of the camera responding to changing light. I watched to see whether the pupil of the eye was opening and closing in response to the apparently changing light. When it did contract in the bright light and dilate in the dark, it seemed out of sync with the lighting, as if some other process were also involved.

The blank, black screen surprised in that the filmed image was so bright and clearly visible, that it enhanced the darker tones without hiding the bright ones. This moved the balance of the medium in favour of the dark particles of the film emulsion—and their calming solidity—whilst reducing the effect of the more frenetic, dazzling, and more anxiety-provoking light areas, so that the piece had a soft, peaceful atmosphere.

Moving into the final chamber of the exhibition, three projector pieces were evident. Directly ahead on the far wall at the end of the gallery was much the largest projection in the show, as apart from the front window, all have been intimately-sized frames less than a metre across, placed on the wall at head height.

Tree Reflection #4 (1998) extended from above head height down to the floor. It was taller than the normal aspect ratio and at least as wide as an adult's arm span wide. The genres of still life and portraiture have been visited in the front of the gallery, so now we have had landscape (or riverscape)—a vista—the outdoors.

The camera view was the opposite bank of a river, a central tree and sky behind. There was a horizontal central axis where the river meets the bank and around this area, the reflection of the scene took place, appearing in the river below at the start of the cycle.

A small water bird swam from right to left on the river (reflection) in the lower half. Partway through the three-minute cycle, the ripples of the river began to appear in the upper half of the sky, and gradually the river and sky halves transformed as they faded out of their own position and into the place of the other, until they completely swapped.

The next clue was that at the end of the cycle, the bird swam left to right, backwards along the river—now in the upper layer of the image. As the bird brought its mirror reflection with it, we read it as swimming upright, whether the real or reflected image was on top.

Optical reprinting, the reversal of film, and fading are all processes that create this puzzle, but the installation added another layer to the film: a piece of glass in front of the projector lens seemed to reflect the film precisely below the upper third of the projection. The result was three stacked trees, with the top two involving a mirror reversal, but the bottom one merely repeating the inverted version and not flipping it upright.

The bottom tree was also a right to left reflection, I think. The complexity of the reflected, relationship between left/right, up/down, forward and backward was by now beginning to outstrip my powers, so I accepted that that puzzle will remain a mystery for the moment.

As I watched Tree Reflection #4 (1998), I was aware that periodically a light was cast into the room from an adjacent low down projector piece: Clock Screen #2 (2007). This brightness was cyclic and lasted for a few seconds, briefly de-contrasting the projected images of the other two works, but with enough time between bright episodes (it was a two-minute film loop) not to dominate or have an adverse effect.

This installation had a different character from the others, which had solid fixed screens; its screen was a delicate piece of white paper in portrait format, just larger than A4 size. It was suspended just above head height by two pieces of fine thread from the moving second hand of a downward-facing clock. The screen completed a rotation every minute, so for a small proportion of that rotation it was able to catch the projected image reflected up to it at a sharp angle by a small mirror near the lens of a projector on the floor.

The projected image itself was a time-lapse record of a travelling beam of sunlight, and when caught on the paper screen, appears as a narrow, bright diagonal beam changing by its own movement and the movement of the screen.

The effect of the installation is to remind one of solar coincidence and orbits, drawing on the impact of the sun on the Earth and in space. Similar to the way that in space, you don't see travelling light unless it hits an object which has the properties to reflect it, I felt as if this was happening in the room: the ceiling area was the darkness of space in which light, if it fell there, was not visible. This piece expands the idea of the travelling sunbeam, human clock time and solar time from Metronome #2 in the front of the gallery, also connecting the idea of cycles of film loops with solar cycles.

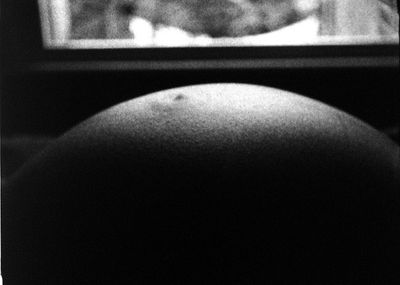

Finally I came to Breathing #2 (1978). In the most secluded corner of the third chamber, back next to the entrance, a small screen at standing height showed a closeup view of the dome of an almost full-term pregnant abdomen. Although it is easy to think about this as pertaining to Sherwin's own position as a father, his sensitivity in the piece transcends that to take on a monumental, global aspect: the universal perspective of being the baby inside, surrounded by a domestic interior and beyond that, the inhabited world through the window.

The frame of the film was divided horizontally across its top quarter by a bright and less sharp view of, and through, a picture window, where a line of washing sags into a concave curve—as if mirroring the convex curve below. This mirror line division is important because like in Tree Reflection #4 opposite, it connoted the difference between two elemental mediums: air and water. In addition to this was another binary pairing of opposites: inside, unborn, darkness, vicarious absorption of nutrients and oxygen; outside, light, sensory stimuli and all the uncertainties of impending escalating autonomy (including breathing).

As breathing caused the abdomen to rise and fall, the light in the whole film frame changed. Rising on the in-breath towards the window ledge, the dome appears to reduce the light entering the camera, but at the same time the image becomes sharper. On the out-breath, the abdomen fell and the image became brighter but less sharp. This suggested to me that the aperture was being opened when the abdomen fell, exaggerating any effect of added light being allowed into the camera, then stopped down when the abdomen rose to allow in less light to the camera, but greater depth of field.

Partway through watching, I noticed that the screen was painted black in the dome portion and white in the window portion above. Like Eye #2, the black screen reduced any light scatter and emphasised the grain and solidity of the film, while the white portion appeared more frenetic with light glare. A push and pull effect between light and darkness was created as each breath moves time closer to the baby's birth, the in-breath moving towards the light of the uncertain outside world, the out-breath falling back to the safe darkness of the mother—the baby's present home.

Light Cycles was a subtle, interconnecting thread of light sequences that lead us through a set of explorations in time. It was well worth standing for a few minutes to think deeply about what was actually there, because what at first may have appeared baffling then revealed its detail, many nuances, connections and questions of being.

Each piece was positioned with the greatest thought about how it should be approached and viewed. The relationship of each piece to the others was carefully considered in terms of its concept, impact, the ambient light that fell upon it and the light that it cast. Light itself is an agent that Sherwin channels: touching, revealing but moving on past instances in time, in lives, using his expertise and sensitivity in the media of film and installation to show us local detail, connected to the greater cycles of the universe. —[O]