At São Paulo's Espaço Delirium, Sound and Memory Intertwine

From the small balcony of Espaço Delirium, an independent project space overlooking Rotary Square in downtown São Paulo, a presence makes itself known through a medley of familiar sounds.

Left to right: Ricardo Carioba, untitled (2022). Intersection between shapes, sphere and square. 56 x 60 x 4 cm; untitled (2022). Spherical suspended object. 33 x 33 x 43 cm. Exhibition view: cápsula vazia caindo no chão de concreto (empty shell dropping on concrete floor), Espaço Delirium, Såo Paulo (15 June–9 July 2022). Courtesy Espaço Delirium.

Walking up the short flight of stairs towards the front room of the mid-century two-storey building, those sounds get louder, inhabiting the walls themselves, as if attempting to push through and engulf the building's exterior in its entirety.

This somewhat soothing melody arises from Ricardo Carioba's untitled (2022), shown in a joint exhibition with Juliana Frontin, titled empty shell dropping on concrete floor (15 June–9 July 2022). Through a microphone strategically placed inside the building's mailbox, Carioba's work records and modulates the sounds produced by all presences—people chattering, cars, basketballs bouncing—that pass by in Espaço Delirium's Santa Cecília neighbourhood.

Along the gallery walls, two figures made of fibreglass and wood by Carioba, both untitled (2022), are covered in a dense layer of industrial, reflective automotive paint. The first is a grey, alien-like oval figure that seems to leak from the corner of the room.

The second is an orchestrated intersection between a circle and square that nods to the history of Brazilian Constructivism, defined by Concretism and Neo-Concretism, by which forms of abstraction found footing within mid-20th century Brazil, with the latter rejecting the former's rationalist approach for a more grounded, phenomenological attitude.

As if to make a statement, the shapes in Carioba's second sculpture become one, with its form referencing the play between negative and positive geometries seen in works like Lygia Pape's woodcut on Japanese paper series, 'Sem Título: Tecelar' (Untitled: Weaving), made between 1955 and 1959.

Movements, lines, and sounds coexist without segregation, appearing to challenge whatever limits that existed between interior and exterior in 20th-century Brazilian abstraction, as defined by Grupo Ruptura and Grupo Frente and the two aforementioned styles they espoused, Concretism and Neo-Concretism, from their bases in the country's two main cities, Rio de Janeiro and Sāo Paulo.

Facing the opposite wall is a small, C.C.T.V. Kodo monitor with headphones attached; it is installed alongside a black-and-white video documenting artist Juliana Frontin taking a hammer to a piece of architecture that seems familiar. The work, 06.06.22 – 15:45 (2022), is titled after the date and time the action occurred.

Through the headphones, we hear the compressed techno track (Frontin is a known D.J. in the São Paulo night scene, especially through their project FRONTINN), that the artist listened to while hammering the cabinet and wall to dust. It takes a minute to realise that both architectural features from the documentation also exist in the room, right by the monitor.

This double vision creates a play between absence and presence, as the video documents the disappearance of its subject—in this case, the cabinet and the wall—just as that absent subject is reified into an object in the exhibition space.

Only by looking at movements of destruction, as suggested by Frontin's video, does it become possible to rebuild.

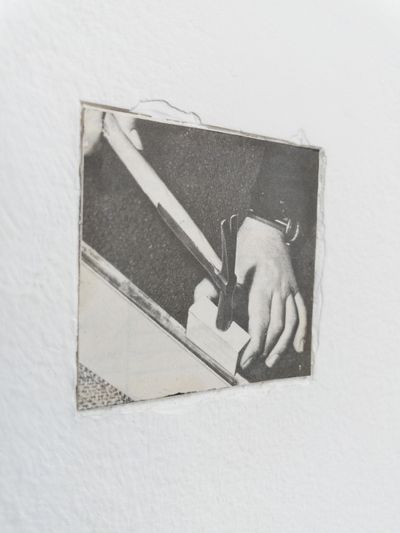

The artist had the cabinet reconstructed for the exhibition, where it is presented side-by-side with the depiction of its destruction, culminating in a final detail that completes the work, and which may not be perceived at first sight. Inhabiting the same wall as the monitor is a small, two-by-two-inch image of an old book depicting a hand hammering a small piece of wood, in what seems like documentation of carpentry work.

A text accompanies the exhibition. It is a fragment of The Aesthetics of Noise (2002) by Danish theorist Torben Sangild translated into Portuguese.1 The author talks about an 'unreal, disorienting sound picture, "the-not-quite-really-there-sound"'—a concept that also describes the space the artists have created in this exhibition, which invites visitors to perceive the acoustics and affects that coexist within a constructed environment.

As a thrust towards the idea of space as both a concept and lived reality, Carioba and Frontin's works entwine in this exhibition as if to contest a kind of dual perception the Brazilian context is fated to unlearn. One that is ingrained in the very history of Brazilian abstraction, splintered between two cities, two groups, and two ideas—one, rational and concrete, the other, abstract, personal, and phenomenological.

Only by looking at movements of destruction, as suggested by Frontin's video, does it become possible to rebuild something—a logic that seems to likewise apply to history as seen from a contemporary perspective. Carioba's audio and sculptural works, meanwhile, in their compositional unity, show that it is possible to move forward.

Set to end with a party on its last day, empty shell dropping on concrete floor feels like a subtle barb aimed directly at Brazil's idiosyncrasies—especially under the Bolsonaro government's bans and persecutions of the cultural scene,2 and in particular towards queer artists.

In this context, awareness of the environment is crucial, especially when it comes to what that environment demands from bodies and their actions. Sometimes, it's about taking it all in and letting it be; other times, things must be broken down. —[O]

1 Torben Sangild, The Aesthetics of Noise, (DATANOM, 2002), p.18, https://www.ubu.com/papers/noise.html.

2 Dom Philips, '"This exhibition contains nudity": the front line of Brazil's culture wars', The Guardian, 30 November 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/nov/30/exhibition-nudity-brazil-culture-wars-sao-paulo-mam-masp-modern-art.